Abstract

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disorder in which patients cycle between active disease and remission. Budesonide multi-matrix (MMX) is an oral second-generation corticosteroid designed to deliver active drug throughout the colon. In pharmacokinetic studies, the mean relative absorption of budesonide in the region between the ascending colon and the descending/sigmoid colon was 95.9 %. In 2 identically designed, phase 3 studies (CORE I and II), budesonide MMX 9 mg once daily was efficacious and well tolerated for induction of remission of mild to moderate UC. Clinical and endoscopic remission rates were 17.9 % (CORE I) and 17.4 % (CORE II) for budesonide MMX 9 mg compared with 7.4 and 4.5 %, respectively, with placebo (p < 0.05, budesonide MMX 9 mg vs. placebo in both studies), 12.1 % with mesalamine 2.4 g, and 12.6 % with budesonide controlled ileal release capsules 9 mg. A 12-month maintenance therapy study suggested that budesonide MMX 6 mg may prolong time to clinical relapse: Median time was >1 year with budesonide MMX 6 mg versus 181 days (p = 0.02) with placebo; however, further studies are needed. In the CORE studies, budesonide MMX exhibited a favorable safety profile; the majority of adverse events were mild or moderate in intensity, and serious adverse events were uncommon. Furthermore, rates of potential glucocorticoid-related adverse events were comparable across treatment groups. The long-term (12-month) safety of budesonide MMX appears to be comparable with placebo. Data support budesonide MMX in the management algorithm of UC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disorder involving the colonic mucosa. It is characterized by periods of active symptomatic disease interspersed with periods of clinical remission [1]. A 2012 systematic review indicated worldwide UC prevalence rates of up to 249 per 100,000 persons in North America and 505 per 100,000 persons in Europe; the highest reported annual incidence rates of UC were 19.2 per 100,000 person-years in North America and 24.3 per 100,000 person-years in Europe [2]. The highest incidence appears to occur during the age range of 20–30 years, although there is some evidence for a second peak in incidence later in life [2].

Endoscopic examination of the colon in patients with UC reveals a number of characteristic changes seen in the mucosa, including loss of vascular pattern, erythema, granularity, friability, erosions, and ulceration [1, 3]. Mucosal healing, which has been defined as complete resolution of the visible alterations or lesions, regardless of their baseline nature or severity, is emerging as an important goal in the management of inflammatory bowel diseases such as UC; increasing evidence indicates that mucosal healing is associated with reductions in the number of disease flares, hospitalizations, and the need for colectomy in patients with UC [4].

Classic symptoms of UC include rectal bleeding, diarrhea, urgency, tenesmus, and abdominal pain [1], and these can impose a substantial burden on patients. Patients with UC report problems in a number of aspects of their daily lives, including withdrawal from social situations, employment disruption, increased anxiety, and decrease in health-related quality of life [5–7].

Current US [8] and European [9] guidelines recommend treatment with 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) as first-line therapy for the induction of remission in patients with mild to moderate UC; such treatment is considered most effective when combinations of both topical and oral preparations are used [8, 9]. Corticosteroids may be indicated in patients in whom 5-ASA formulations are ineffective in inducing remission [8, 9]. However, first-generation corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are associated with a number of potential safety concerns, including increased risks of serious infections, bone disease, the development of cushingoid features, and increased risk of mortality [8, 10–12].

Budesonide is an orally active, second-generation corticosteroid that has affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor approximately 8.5-fold, 15-fold, and 195-fold greater than those of dexamethasone [13], prednisolone [14], and hydrocortisone [14], respectively. A number of oral formulations are available, including oral budesonide controlled ileocolonic release (CIR) (Entocort® EC, AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, DE), budesonide capsules [Budenofalk® capsules, Dr Falk Pharma, Freiburg, Germany (not available in the USA)], and budesonide multi-matrix (MMX®; Santarus, Inc.; Raleigh, NC). Budesonide CIR and budesonide capsules are not indicated for UC, but are indicated only for induction of remission of mild to moderate Crohn’s disease (CD) involving the ileum and/or ascending colon; budesonide CIR is also indicated for maintenance of CD remission. However, budesonide MMX is indicated for induction of remission of mild to moderate UC. Based on data from the Colonic Release Budesonide (CORE) I and II studies [15, 16], which are described later in this review, an updated UC treatment algorithm has recommended budesonide MMX before the introduction of conventional corticosteroids for the induction of remission in patients for whom 5-ASA therapy has been unsuccessful, or for those who relapse during 5-ASA therapy [10].

Several guidelines, developed before the availability of budesonide MMX, do not recommend oral conventional or second-generation corticosteroids for the maintenance of remission in UC [8, 9]; however, data are accumulating to support an acceptable tolerability profile for second-generation corticosteroids. One study, which evaluated the long-term (1-year) safety of budesonide MMX in patients with UC, indicated that oral budesonide MMX 6 mg had a safety profile similar to that of placebo [17]. In addition, the CD clinical trials of budesonide CIR and budesonide capsules support the safety of oral budesonide during long-term (e.g., 1 year) exposure in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [18–28]. This article reviews the efficacy and safety profile of budesonide MMX for the treatment of UC.

Pharmacokinetic Properties of Budesonide

Budesonide is a second-generation corticosteroid with low systemic bioavailability after oral administration because of extensive (~90 %) first-pass hepatic metabolism [29]. It is metabolized predominantly by hepatic cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) enzymes to form 2 principal metabolites: 16α-hydroxyprednisolone and 6β-hydroxybudesonide [30]. These metabolites comprise only 1–10 % of the biologic activity of the parent compound [29]. Following oral administration, approximately 75 % of the dose is excreted in the urine and feces [29].

The MMX formulation has been designed to target orally administered drugs to sites in the distal colon [31]. This delivery system utilizes an outer pH-dependent coating consisting of a hydrophilic and inert polymer matrix, which allows passage of active drug through the gastrointestinal tract to the ileum, where the outer layer of the capsule begins to dissolve at a pH > 7.0. The active drug is therefore delivered uniformly throughout the length of the colon, thus minimizing systemic absorption, in contrast to conventional corticosteroid absorption (Fig. 1) [31, 32]. MMX technology has been used effectively for the delivery of 5-ASA to the colon, whereby mesalamine MMX is being used for both induction [31, 33–35] and maintenance [36, 37] of remission in patients with mild to moderate UC.

In pharmacokinetic studies with budesonide MMX 9 mg, the mean relative absorption of budesonide in the region between the ascending colon and the descending/sigmoid colon was 95.9 % with drug detected between 4 and >24 h postdose (Fig. 2) [38]. This relative absorption profile contrasts with the absorption of other oral budesonide formulations: For example, following administration of budesonide CIR, approximately 69 % of the dose is absorbed in the distal ileum and ascending colon, the sites typically affected by inflammation in patients with CD [39]. Release of the active drug from budesonide CIR and budesonide capsules occurs in a more acidic environment than with budesonide MMX, with absorption beginning at pH values of 5.5 and 6.4, respectively [40, 41].

Scintigraphic image in a healthy volunteer showing dispersion of [153Sm]-labeled budesonide MMX in the colon. The image was obtained approximately 7 h after administration. Reprinted with permission from Brunner et al. [38]

In a study of healthy volunteers, the mean lag time (t lag) between administration of budesonide MMX 9 mg and detection of budesonide in plasma was 6.8 h; the mean peak plasma concentration (C max) was 1768.7 pg/mL, and the time to C max (t max) was 14.0 h [38]. Administration of budesonide MMX with food resulted in significant decreases in both C max (p = 0.03) and systemic exposure as measured by the area under the concentration–time curve to 48 h (AUC48h; p = 0.008), but these changes are not considered to be clinically meaningful [38]; hence, budesonide MMX may be administered with or without food [42]. After single dosing in healthy volunteers, C max, AUC0–36 h, AUC0–∞, and half-life (t 1/2) of budesonide MMX 9 mg were comparable to those of budesonide CIR 9 mg [43]. Median t lag was 6 h for both 9- and 6-mg doses of budesonide MMX, compared with 1 h for budesonide CIR 9 mg [43].

Because budesonide is metabolized predominantly in the liver, bioavailability may be increased in patients with impaired liver function. In a study in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis who received a single dose of budesonide 3 mg (non-MMX formulation), patients with late-stage (stage IV) disease showed significantly greater systemic exposure to budesonide than those patients with early-stage (stage I–II) disease [44]. Mean C max was 1.5 ng/mL in patients with early-stage disease, compared with 4.9 ng/mL in patients with late-stage disease (p < 0.05), while mean AUC0-∞ values were 5.1 and 23.2 h ng/mL (p < 0.01), respectively. Median t 1/2 was also numerically higher in patients with late-stage disease than in those with early-stage disease (5.8 vs. 2.3 h, respectively), but this difference was not statistically significant [44]. In addition, multiple dosing resulted in a significant increase in AUC0–8 h at day 21 in patients with late-stage primary biliary cirrhosis compared with early-stage primary biliary cirrhosis (14.0 vs. 5.0 h ng/mL, respectively; p < 0.05) [44]. For this reason, patients with hepatic impairment who are receiving treatment with budesonide MMX should be monitored for symptoms of hypercorticism [42].

A drawback of corticosteroid treatment is decreased drug accumulation in many patients, possibly resulting from polymorphisms in the multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1) gene [45, 46]. This phenomenon may result in the so-called glucocorticosteroid resistance and subsequent failure of patients to respond to therapy; data show that up to one-sixth of UC patients may be steroid resistant [45, 46]. However, in a study of healthy volunteers or patients with early-stage primary biliary cirrhosis, there were no appreciable differences in C max or AUC and, thus, drug disposition, following administration of budesonide 3 mg (non-MMX formulation) between individuals who were homozygous for 2 common single nucleotide polymorphisms of the MDR1 gene [45].

Budesonide MMX for the Treatment of UC

Budesonide MMX for the Induction of Remission of UC

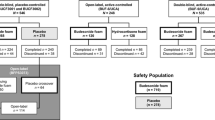

The efficacy and safety of budesonide MMX for the induction of remission in patients with mild to moderate UC [UC disease activity index (UCDAI) score 4–10] have been investigated in 2 identically designed, randomized trials: CORE I and II (Table 1) [15–17, 47]. CORE I compared budesonide MMX 9 mg and 6 mg with mesalamine 2.4 g and placebo, whereas CORE II compared the same doses of budesonide MMX with budesonide CIR 9 mg and placebo. In both studies, treatment was administered for 8 weeks, and the primary endpoint was clinical and endoscopic remission at week 8. Remission was defined as a UCDAI score ≤1, with scores of 0 for rectal bleeding and stool frequency, no mucosal friability on colonoscopy, and a reduction of ≥1 point in endoscopic index score from baseline [15, 16].

In both studies, clinical and endoscopic remission was achieved in a significantly greater percentage of patients receiving budesonide MMX 9 mg compared with placebo (Table 1). In CORE I, remission at week 8 was achieved in 17.9 % of patients receiving budesonide MMX 9 mg, compared with 7.4 % (p = 0.01) in the placebo group and 12.1 % in the group receiving mesalamine (Fig. 3a) [15]. In CORE II, the 8-week remission rate was 17.4 % in patients receiving budesonide MMX 9 mg, compared with 4.5 (p = 0.005) and 12.6 % (p = 0.048) in the placebo and budesonide CIR groups, respectively (Fig. 3b) [16]. In addition, a subgroup analysis in the CORE II study showed that a significantly greater percentage of patients with left-sided UC achieved clinical and endoscopic remission with budesonide MMX 9 mg than with placebo (17.7 vs. 5.8 %, respectively; p = 0.03); the percentage of patients with extensive disease who reached clinical and endoscopic remission was also numerically higher with budesonide MMX 9 mg than with placebo (13.8 vs. 0 %, respectively), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.10) [16].

Combined clinical and endoscopic remission rates at week 8 in the CORE I (a) and CORE II (b) studies. Clinical and endoscopic remission was defined as a UCDAI score ≤1, with scores of 0 for rectal bleeding and stool frequency, no mucosal friability on colonoscopy, and a reduction from baseline of ≥1 point in endoscopic index score. CI confidence interval, CIR controlled ileal release. Reprinted with permission from Sandborn et al. [15] and Travis et al. [16]

In CORE I, an analysis by disease severity subgroup indicated that in patients with mild UC (UCDAI score 4 or 5) who received budesonide MMX 9 mg or placebo, clinical improvement (defined as a ≥3-point reduction in UCDAI score) was achieved in 44.4 and 25.0 % of patients, respectively; corresponding figures in patients with moderate disease (UCDAI score ≥6 and ≤10) were 39.7 and 30.1 %, respectively. Furthermore, the mucosal healing rate was greater with budesonide MMX 9 mg than with placebo in patients with proctosigmoiditis (32.4 vs. 19.5 %, respectively; p = 0.20) and left-sided UC (40.6 vs. 26.5 %, respectively; p = 0.22). A similar numeric difference favoring budesonide MMX 9 mg was also observed in patients with extensive UC (16.1 vs. 10.0 % with placebo), but this difference also was not statistically significant (p = 0.39) [15].

In a pooled analysis of the CORE I and CORE II studies [47], patients treated with budesonide MMX 9 mg were at least 3 times more likely to achieve clinical and endoscopic remission versus placebo [OR 3.3 (95 % CI 1.7–6.4)] [47]. Budesonide MMX 9 mg was statistically significantly more efficacious versus placebo for several subgroups: males, females, patients ≤60 years, patients with prior mesalamine use, patients without prior mesalamine use, patients with mild UC at baseline, patients with moderate UC at baseline, patients with proctosigmoiditis, patients with left-sided UC, patients with UC duration >1 to ≤5 years, and patients with UC duration >5 years.

Budesonide MMX for the Maintenance of Remission of UC

The efficacy of budesonide MMX for the maintenance of UC remission was investigated in a study of patients who had achieved clinical and endoscopic remission in the CORE I and II studies [15, 16] or patients in CORE I and II who had received an additional 8 weeks of treatment (budesonide MMX 9 mg) in an open-label study (Table 1) [17, 48]. In the maintenance study, patients were randomized to receive budesonide MMX 6 mg or placebo for up to 12 months; the primary efficacy endpoint was clinical remission, assessed after 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. The median time to clinical relapse (defined as rectal bleeding, stool frequency ≥1–2 stools per day, or both) was 181 days in the placebo group, but was not reached in the budesonide MMX group (p = 0.02; Fig. 4) [17]; at 12 months, the probability of relapse was 59.7 and 40.9 %, respectively [17]. However, the percentage of patients in whom remission was maintained for up to 12 months did not differ significantly between the groups, a finding that was potentially attributable to insufficient statistical power. Therefore, the potential benefit of budesonide MMX in maintenance of remission is currently unclear and further studies are required.

Adverse Effects

In general, the budesonide molecule exhibits a more favorable safety profile than first-generation oral corticosteroids such as prednisone or prednisolone. For example, in a 10-week, double-blind, double-dummy study in 176 patients with CD who received tapering doses of prednisolone or budesonide CIR for 10 weeks, the incidence of glucocorticoid-related adverse effects was significantly lower with budesonide than with prednisolone (33 vs. 55 %, respectively; p = 0.003). In addition, suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, assessed by measurement of the mean morning plasma cortisol concentration, was significantly greater with prednisolone than with budesonide CIR after 4 weeks (p < 0.001) and 8 weeks (p = 0.02) [49].

The favorable adverse event (AE) profile of budesonide MMX in UC patients was demonstrated in the CORE I and II studies [15, 16]. The incidence of AEs in patients receiving budesonide MMX 9 mg or 6 mg was 57.5 and 58.7 %, respectively, in CORE I, and 55.5 and 62.5 %, respectively, in CORE II. In both studies, the majority of AEs were mild or moderate in intensity, and the incidence of serious AEs was low and similar across all treatment groups. The most commonly reported AEs in patients receiving budesonide MMX were UC, headache, and nausea (Table 2) [15, 16]. In a pooled analysis of CORE I and II, the incidence rates of predefined potential glucocorticoid-related adverse effects (acne, fluid retention, flushing, hirsutism, insomnia, mood changes, moon face, sleep changes, striae rubrae) were comparable for budesonide MMX 9 mg (10.2 %), 6 mg (7.5 %), and placebo (10.5 %) [42]. The most common predefined potential glucocorticoid-related adverse effects with budesonide MMX 9 mg versus placebo were mood changes (3.5 vs. 4.3 %, respectively) and sleep changes (2.7 vs. 4.7 %, respectively) [42]. In the 1-year budesonide MMX 6 mg maintenance study, the safety profile of budesonide MMX was comparable to that of placebo [17].

Pharmacoeconomics of UC

The chronic and relapsing nature of UC means that the condition imposes a substantial burden on healthcare resources, and this burden extends to society as a whole when indirect costs resulting from lost productivity are taken into account. One US study estimated that the direct medical costs of UC were $2.7 billion [50], with health insurer and patient out-of-pocket expenditures between $390 million and $920 million [51]. Another study reported that mean estimated annual healthcare insurer expenditures were significantly greater for patients with UC than for patients without UC ($7424 vs. $4530, respectively, p < 0.001; expenditures adjusted to 2010 US dollars) [51], and that mean annual out-of-pocket costs for UC patients were $1280 [51].

Treatments that increase the likelihood of achieving and maintaining remission in UC may provide cost savings through decreased use of healthcare resources. However, the economic benefits of treatment with conventional corticosteroids in UC may be overestimated in economic models that failed to take into account the long-term adverse effects of these medications, such as the increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures [52]. It remains to be determined whether the budesonide molecule, or a particular budesonide formulation, provides an economic benefit compared with conventional oral corticosteroids, although the decreased incidence of systemic adverse effects associated with budesonide may result in long-term economic benefits.

Patients with UC are often nonadherent to treatment [53–55], and this has substantial clinical and economic consequences, including increased risk of UC relapse, decreased quality of life, and increased healthcare expenditures from hospitalizations and emergency room treatments [56, 57]. Oral formulations of budesonide have several advantages compared with conventional oral corticosteroids, including once-daily dosing [15, 16, 42, 58], targeted absorption in the ileocolonic region or colon (depending on formulation) [39], and favorable AE profiles [15, 16, 28]. As a result, such formulations may improve patients’ adherence to therapy. In a study of maintenance treatment, a greater percentage of UC patients receiving oral 5-ASA once daily were adherent to treatment after 3 and 6 months compared with patients receiving conventional twice-daily or three-times-daily dosing [3 months: 100 vs. 70 %, respectively (p = 0.04); 6 months: 75 vs. 70 %, respectively (p = 0.8)]. Furthermore, more patients were “very satisfied” with dosing once daily (83 %) than with dosing twice daily or three times daily (60 %), although this difference was not statistically significant [59].

Conclusions

The budesonide MMX formulation delivers the drug throughout the colon [31], in contrast to other controlled-release oral formulations of budesonide, which are targeted to the distal ileum and ascending colon—the sites primarily affected by inflammation in CD [39]. Budesonide MMX has been shown to be efficacious and well tolerated for the induction of remission in patients with mild to moderate UC [15, 16], and the data currently available suggest that it may also be efficacious and well tolerated for maintaining long-term (up to 1 year) UC remission. The long-term safety of budesonide MMX in patients with UC was comparable to that of placebo, but these findings are limited to the single 12-month study [17]. However, several studies have evaluated the use of oral formulations of budesonide as maintenance therapy in patients with CD [18–28], and these have provided support for the long-term (≥1 year) safety of budesonide for maintenance of remission of inflammatory bowel disease. Budesonide MMX may also offer pharmacoeconomic benefits by potentially increasing adherence to treatment via once-daily dosing and decreasing the risk of AEs compared with conventional oral corticosteroids. However, more work is needed in this area.

References

Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1606–1619.

Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54.

Walsh A, Palmer R, Travis S. Mucosal healing as a target of therapy for colonic inflammatory bowel disease and methods to score disease activity. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014;24:367–378.

Pagnini C, Menasci F, Festa S, Rizzatti G, Delle FG. “Mucosal healing” in ulcerative colitis: between clinical evidence and market suggestion. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:54–62.

Kalafateli M, Triantos C, Theocharis G, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a single-center experience. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:243–248.

Loftus EV Jr. A practical perspective on ulcerative colitis: patients’ needs from aminosalicylate therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:1107–1113.

Nurmi E, Haapamäki J, Paavilainen E, Rantanen A, Hillilä M, Arkkila P. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease on health care utilization and quality of life. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:51–57.

Kornbluth A, Sachar DB, The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:501–523.

Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:991–1030.

Danese S, Siegel CA, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Review article: integrating budesonide-MMX into treatment algorithms for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1095–1103.

Lewis JD, Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, et al. Immunosuppressant medications and mortality in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1428–1435.

Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn’s disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621–630.

Esmailpour N, Högger P, Rohdewald P. Binding kinetics of budesonide to the human glucocorticoid receptor. Eur J Pharm Sci. 1998;6:219–223.

Brattsand R. Overview of newer glucocorticosteroid preparations for inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1990;4:407–414.

Sandborn WJ, Travis S, Moro L, et al. Once-daily budesonide MMX® extended-release tablets induce remission in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: results from the CORE I study. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1218–1226.

Travis SP, Danese S, Kupcinskas L, et al. Once-daily budesonide MMX in active, mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: results from the randomised CORE II study. Gut. 2014;63:433–441.

Sandborn WJ, Danese S, Ballard ED, et al. Efficacy of budesonide MMx® 6 mg QD for the maintenance of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: results from a phase III, 12 month safety and extended use study [Abstract Su2080]. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S-564.

Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, The Canadian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group, et al. Oral budesonide as maintenance treatment for Crohn’s disease: a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:45–51.

Ferguson A, Campieri M, Doe W, Persson T, Nygard G, The Global Budesonide Study Group. Oral budesonide as maintenance therapy in Crohn’s disease—results of a 12-month study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:175–183.

Gross V, Andus T, Ecker KW, The Budesonide Study Group, et al. Low dose oral pH modified release budesonide for maintenance of steroid induced remission in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1998;42:493–496.

Ewe K, Bottger T, Buhr HJ, Ecker KW, Otto HF, The German Budesonide Study Group. Low-dose budesonide treatment for prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a multicentre randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:277–282.

Hellers G, Cortot A, Jewell D, The IOIBD Budesonide Study Group, et al. Oral budesonide for prevention of postsurgical recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:294–300.

Hanauer S, Sandborn WJ, Persson A, Persson T. Budesonide as maintenance treatment in Crohn’s disease: a placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:363–371.

Mantzaris GJ, Petraki K, Sfakianakis M, et al. Budesonide versus mesalamine for maintaining remission in patients refusing other immunomodulators for steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:122–128.

Schoon EJ, Bollani S, Mills PR, et al. Bone mineral density in relation to efficacy and side effects of budesonide and prednisolone in Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:113–121.

de Jong DJ, Bac DJ, Tan G, et al. Maintenance treatment with budesonide 6 mg versus 9 mg once daily in patients with Crohn’s disease in remission. Neth J Med. 2007;65:339–345.

Cortot A, Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, et al. Switch from systemic steroids to budesonide in steroid dependent patients with inactive Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2001;48:186–190.

Lichtenstein GR, Bengtsson B, Hapten-White L, Rutgeerts P. Oral budesonide for maintenance of remission of Crohn’s disease: a pooled safety analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:643–653.

Ryrfeldt Å, Andersson P, Edsbäcker S, Tönnesson M, Davies D, Pauwels R. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of budesonide, a selective glucocorticoid. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1982;122:86–95.

Jönsson G, Åström A, Andersson P. Budesonide is metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) enzymes in human liver. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:137–142.

Prantera C, Viscido A, Biancone L, Francavilla A, Giglio L, Campieri M. A new oral delivery system for 5-ASA: preliminary clinical findings for MMx. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:421–427.

Fiorino G, Fries W, De La Rue SA, Malesci AC, Repici A, Danese S. New drug delivery systems in inflammatory bowel disease: MMX™ and tailored delivery to the gut. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1851–1857.

D’Haens G, Hommes D, Engels L, et al. Once daily MMX mesalazine for the treatment of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a phase II, dose-ranging study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1087–1097.

Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Boddu P, et al. Effect of once- or twice-daily MMX mesalamine (SPD476) for the induction of remission of mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:95–102.

Kamm MA, Sandborn WJ, Gassull M, et al. Once-daily, high-concentration MMX mesalamine in active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:66–75.

Kamm MA, Lichtenstein GR, Sandborn WJ, et al. Randomised trial of once- or twice-daily MMX mesalazine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2008;57:893–902.

D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Barrett K, Hodgson I, Streck P. Once-daily MMX® mesalamine for endoscopic maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1064–1077.

Brunner M, Ziegler S, Di Stefano AF, et al. Gastrointestinal transit, release and plasma pharmacokinetics of a new oral budesonide formulation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:31–38.

Edsbäcker S, Bengtsson B, Larsson P, et al. A pharmacoscintigraphic evaluation of oral budesonide given as controlled-release (Entocort) capsules. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:525–536.

Lundin P, Naber T, Nilsson M, Edsbäcker S. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of budesonide controlled ileal release capsules in patients with active Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:45–51.

Kolkman JJ, Mollmann HW, Mollmann AC, et al. Evaluation of oral budesonide in the treatment of active distal ulcerative colitis. Drugs Today (Barc). 2004;40:589–601.

Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Uceris (budesonide) extended release tablets, for oral use [package insert]. Raleigh, NC: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2014.

Nicholls A, Harris-Collazo R, Huang M, Hardiman Y, Jones R, Moro L. Bioavailability profile of Uceris MMX extended-release tablets compared with Entocort EC capsules in healthy volunteers. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:386–394.

Hempfling W, Grunhage F, Dilger K, Reichel C, Beuers U, Sauerbruch T. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic action of budesonide in early- and late-stage primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2003;38:196–202.

Dilger K, Cascorbi I, Grunhage F, Hohenester S, Sauerbruch T, Beuers U. Multidrug resistance 1 genotype and disposition of budesonide in early primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2006;26:285–290.

Farrell RJ, Kelleher D. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Endocrinol. 2003;178:339–346.

Sandborn WJ, Danese S, D’Haens G, et al. Induction of clinical and colonoscopic remission of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with budesonide MMX 9 mg: pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:409–418.

Travis S, Ballard ED. Induction of remission with oral budesonide MMXVR (9 mg) tablets in patients with mild to moderate, active ulcerative colitis: a multicenter, open-label efficacy and safety study [Abstract]. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:S20.

Rutgeerts P, Löfberg R, Malchow H, et al. A comparison of budesonide with prednisolone for active Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:842–845.

Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in United States children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907–1913.

Gunnarsson C, Chen J, Rizzo JA, Ladapo JA, Lofland JH. Direct health care insurer and out-of-pocket expenditures of inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from a US national survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3080–3091.

Bodger K. Cost effectiveness of treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29:387–401.

Feagins LA, Iqbal R, Spechler SJ. Case-control study of factors that trigger inflammatory bowel disease flares. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4329–4334.

Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, Hanauer SB. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2929–2933.

Kane SV, Brixner D, Rubin DT, Sewitch MJ. The challenge of compliance and persistence: focus on ulcerative colitis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14:s2–s12.

Kane SV. Systematic review: adherence issues in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:577–585.

Mitra D, Hodgkins P, Yen L, Davis KL, Cohen RD. Association between oral 5-ASA adherence and health care utilization and costs among patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:132.

AstraZeneca LP. Entocort EC (budesonide) capsules [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca LP. 2012.

Kane S, Huo D, Magnanti K. A pilot feasibility study of once daily versus conventional dosing mesalamine for maintenance of ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:170–173.

Acknowledgments

Technical editorial assistance was provided, under the direction of the author, by Mary Beth Moncrief, PhD, and Michael Shaw, PhD, Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, Pennsylvania. Funding for this editorial support was provided by Salix, a Division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, Bridgewater, NJ, USA.

Funding statement

The author did not receive any compensation for development of this manuscript. Salix, a Division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, provided funding to Synchrony Medical Communications for editorial support. Salix, the study sponsor, did not actively contribute to the content or have a role in the decision to submit, but reviewed the copy for scientific accuracy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

G Lichtenstein reports serving as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories/AbbVie, Actavis/Warner Chilcott, Alaven (now part of Meda Pharmaceuticals), Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Hospira, Janssen Biotech, Inc., Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc./American Regent, Inc., Pfizer Inc., Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., Romark Laboratories, LC, Salix, a Division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, Santarus, Inc., formally a subsidiary of Salix, Shire plc, Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., UCB, and Warner Chilcott; receiving research funding/grants from Actavis/Warner Chilcott, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Janssen Biotech, Inc., Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., Salix, Santarus, Shire plc, and UCB; receiving honoraria from Clinical Advances in Gastroenterology and Gastroenterology and Hepatology (via Gastro-Hep Communications, Inc.), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc./American Regent, McMahon Publishing, Springer Science + Business Media, and UpToDate; and receiving book royalties from SLACK, Inc.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lichtenstein, G.R. Budesonide Multi-matrix for the Treatment of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Dig Dis Sci 61, 358–370 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3897-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3897-0