Abstract

This article explores the potential of artificial intelligence for identifying cases where digital vendors fail to comply with legal obligations, an endeavour that can generate insights about business practices. While heated regulatory debates about online platforms and AI are currently ongoing, we can look to existing horizontal norms, especially concerning the fairness of standard terms, which can serve as a benchmark against which to assess business-to-consumer practices in light of European Union law. We argue that such an assessment can to a certain extent be automated; we thus present an AI system for the automatic detection of unfair terms in business-to-consumer contracts, a system developed as part of the CLAUDETTE project. On the basis of the dataset prepared in this project, we lay out the landscape of contract terms used in different digital consumer markets and theorize their categories, with a focus on five categories of clauses concerning (i) the limitation of liability, (ii) unilateral changes to the contract and/or service, (iii) unilateral termination of the contract, (iv) content removal, and (v) arbitration. In so doing, the paper provides empirical support for the broader claim that AI systems for the automated analysis of textual documents can offer valuable insights into the practices of online vendors and can also provide valuable help in their legal qualification. We argue that the role of technology in protecting consumers in the digital economy is critical and not sufficiently reflected in EU legislative debates.

Similar content being viewed by others

In recent years, consumer markets have increasingly been shaped by new information technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) systems. This development, prompted by leading companies operating consumer-facing platforms, has often been portrayed as contributing to consumer well-being. Indeed, by lowering decision-making and transaction costs, new approaches to data analytics and AI can certainly bring value to consumers (André et al., 2018; Bakos, 1997; Wathieu et al., 2002). At the same time, growing attention has been paid to the ways in which innovative technologies and business models can affect individuals’ rights and behaviour (Helbing, 2019; Jabłonowska et al., 2018; Mirsch et al., 2017).

In the field of consumer law and policy, the use of AI by large businesses has given rise to concerns over the weakening position of consumers, creating an imbalance in the market that is likely to prove unsustainable over the long term. Indeed, AI, in combination with big data, is equipping companies and platforms with enhanced knowledge and unprecedented capacities in relation to their customers: the ability to identify, on a massive scale, their tastes and preferences, strengths and weaknesses, to predict their responses, and to target them with personalised messages aimed at triggering desired behaviours (Grafanaki, 2016; Helberger et al., 2021; Zuboff, 2015). Where AI systems are developed primarily by businesses, and focused on serving their interests (such as increasing profits and market share), there is a risk of consumers becoming not empowered but overpowered by AI.Footnote 1 Similar challenges are also present in other fields transformed by technological developments, in both private and public sectors (Pasquale, 2015; Wood et al., 2019).

Faced with the growing technological sophistication and the associated promises and perils, regulators around the world have begun to contemplate the need for legislative responses. The EU legislature initially took a piecemeal approach, targeting selected problems experienced by vendors (hereafter, “traders”) and consumers. More recently, a more overarching vision for the EU digital economy was presented, covering, on the one hand, competition and the provision of services in online platform markets, and, on the other hand, equally important questions about data governance and artificial intelligence. The ambition is to simultaneously address the downsides of data-driven markets and promote the development of technologies that enhance growth and well-being.

Against this background, the present paper explores the potential of AI to generate insights about business-to-consumer (B2C) practices and to identify noncompliance of digital traders with their obligations. In so doing, it connects several themes which the EU legislature deems important but has yet to consider together. The focus of the discussion remains on five aspects of the relationship between consumers and traders in the digital economy (including platforms) that are prominent in EU regulatory and academic debates, namely, liability, unilateral change, termination, content moderation, and alternative dispute resolution (ADR). In relation to most of these aspects, a range of comparatively detailed obligations are proposed in the new legislation. However, there already exist certain horizontal norms that can serve as a valuable frame of reference for assessing traders’ online practices in B2C relations. That is the case with the analysis of standard terms which providers of digital services typically make available to consumers and which often cover the matters just described. We contemplate and test the possibility of using AI systems in the domain of standard terms control and demonstrate that these indeed can yield important insights about market practices. This illustrates, in our view, the usefulness of researching and implementing systems that support consumer organizations and leverage consumer empowerment in the AI era (Contissa et al., 2018b).

The paper is structured as follows. By way of introduction, we review the challenges faced by consumers in the world of big data and AI and highlight key aspects of the current EU landscape with regard to consumer protection in online commerce. Particular attention is devoted to the recent proposals on platforms and AI as well as to existing provisions on unfair contract terms. Based on this initial discussion, as well as previous academic research, we identify a number of overarching matters recognized as important in the relation between digital service providers and consumers. We then present a system for the automatic detection of potentially unfair terms in consumer contracts, developed as part of the CLAUDETTE project, offering this system as an example of an AI-driven initiative aimed at enhancing consumer protection (Contissa et al., 2018a; Lippi et al., 2019). Based on the dataset prepared for this particular project, we paint the landscape of contract terms used in different digital consumer markets and theorize their categories, with a focus on the previously identified overarching matters. In doing so, the paper provides empirical support for the broader claim that online systems for the automated analysis of textual documents can offer valuable insights into the practices of online traders and valuable help in their legal qualification. We argue that the role of technology in protecting consumers in the digital economy is critical and should accordingly be embraced.

Consumers in the World of Big Data and AI

New information technologies, and especially artificial intelligence, are quickly transforming economic, political, and social spaces. On the one hand, AI provides considerable opportunities for consumers and civil society. For instance, services can be designed and deployed to analyse and summarize massive amounts of product reviews (Hu et al., 2014), detect discrimination in commercial practices (Ruggieri et al., 2010), recognize identity fraud (Wu et al., 2015), or compare prices across a multitude of platforms. On the other hand, these opportunities are accompanied by serious risks, including inequality, discrimination, surveillance, and manipulation. It has indeed been claimed that AI should contribute to the realisation of individual and social interests, and that it should not be “underused, thus creating opportunity costs,” nor “overused and misused, thus creating risks” (Floridi et al., 2018).

The observed development in AI is fostered to a significant degree by the leading providers of digital services, especially online platforms. As traders gain access to vast amounts of personal data (consumers’ preferences, past purchases, etc.) and assume increasingly important social and economic roles, their relationship to consumers’ needs to receive special attention. Thanks to AI, digital service providers can effortlessly use this information to further their commercial goals, potentially to the detriment of consumers’ interest in fair algorithmic treatment, i.e., their interest in not being subject to unjustified prejudice resulting from automated processing.

To better understand the imbalance between the data infrastructures available to businesses and consumers, it is worth looking at the most common methods of machine learning and the ways in which they can be used to surveil, profile, and manipulate consumers. Data infrastructures include methods and tools for collecting, processing, and analysing consumers’ data so as to predict their future behaviour. A sophisticated data infrastructure usually includes all the necessary steps from collecting and sorting the data of interest to then using it for business interests such as advertising and profiling. Conversely, the tools available to consumers are scarce (Curran, 2018). Three approaches to machine learning are discussed here, i.e., supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning—each powerful in its own way but suited to different kinds of tasks.

Supervised learning requires a training set containing a set of input-output pairs, each linking the description of a case to the correct response for that case. Once trained, the system is able to provide hopefully correct responses to new cases. This task is performed by mimicking correlations between cases and responses as embedded in the training set. If the examples in the training set that come closest to a new case (with regard to relevant features) are linked to a certain answer, the same answer will be proposed for the new case. For instance, in product-recommendation and personalised-advertising systems, each consumer feature (e.g., age and gender) and behaviour (e.g., online searches and visited Web pages) is linked to the purchased objects. Thus, if consumers that are most similar to a new consumer are labelled as being inclined to buy a certain product, the system will recommend the same product to the new consumer. Similarly, if past consumers whose characteristic best match those of the new consumer are linked as being responsive to certain stimuli (e.g., an ad), the system will show the same commercial message to the new consumer as well. As these examples show, training a system does not always require a human “teacher” to provide correct answers/predictions to the system, since in many cases answers can be obtained as a side effect of human activities (e.g., purchasing, tagging, clicking), or they can even be gathered “from the wild,” being available on the open Web.

Reinforcement learning is similar to supervised learning, as both involve training by way of examples. However, in the case of reinforcement learning, the machine is presented with a game-like situation where it learns from the outcomes of its own actions. Its aim is to figure out a solution/answer to a certain problem/question through trial and error associated with rewards or penalties (e.g., points gained or lost), depending on the outcomes of such actions. For instance, in a system learning to target ads effectively, rewards may be linked to users’ clicks. Being geared towards maximising its score (utility), the system will learn to achieve outcomes leading to rewards (gains, clicks) and to prevent those leading to penalties.

Finally, in unsupervised learning, the system learns without receiving external instructions, either in advance or as feedback. In particular, unsupervised learning is used in sorting and then categorizing data, and it can identify unknown patterns in data. The task of processing and grouping data is called clustering, and it produces clusters (where the machine can be instructed on the number or granularity of such clusters), i.e., the set of items that present relevant similarities or connections (e.g., purchases that pertain to the same product class or consumers sharing relevant characteristics).

As mentioned, AI systems developed and deployed with a business interest in mind can substantially increase the asymmetry between traders and consumers. In digital markets, certain risks to consumer interests may be further exacerbated by the fact that many technology companies—such as major platforms hosting user-generated content—operate in two- or multi-sided markets. Their main services (search, social network management, access to content, etc.) are offered to individual consumers, but the revenue streams come from advertisers, influencers, and opinion-makers (e.g., in political campaigns). This means not only that all information that is useful for targeted advertising will be collected and used for this purpose, but also that platforms will employ any means to capture users, so that users can be targeted with ads and attempts at persuasion. As a result, the collection of personal data and the data-driven influence over consumer behaviour assume massive proportions, to the detriment of privacy, autonomy, and collective interests. Moreover, online platforms often lack incentives to act impartially and consistently with regard to mediated content. For example, since controversial content has been shown to be particularly effective at capturing consumers’ attention, service providers may not always have an incentive to restrain it (Hagey & Horwitz, 2021).Footnote 2 In other cases, the design of ranking systems and conditions for accessing platforms can result in consumers being prevented from significant opportunities (e.g., discounts, alternative providers). These algorithmic practices are exceedingly difficult to monitor and, on the face of it, can be consistent with terms of service (ToS) accepted by consumers. Standard terms may further include far-reaching exclusions of traders’ liability as well as cumbersome provisions on dispute resolution, thereby additionally shielding providers from outside scrutiny. However, as shown in the following, service providers have been attracting increased regulatory attention and do not operate in a legal vacuum. Moreover, AI can be used not only to further business interests but also to capture valuable insights into businesses practices, and it can help legal practitioners and nongovernmental organisations in their legal assessment of such practices.

Recent Developments and Established Instruments of Consumer Protection in Digital Markets

The Emerging Regulatory Framework for Online Platforms and AI

The risks that AI poses to markets and society, and the structural characteristics of digital consumer markets, have been a subject of lively academic and policy debates over the past years. Indeed, as noted by Zuboff, in the age of surveillance capitalism, where the human experience has become a new “fictional commodity,” raw market dynamics can lead to novel disruptive outcomes (Zuboff, 2015). This is a reason why AI is often perceived as a weapon (O’Neil, 2016) in the hands of businesses, to be used to the detriment of consumers. A particularly determined push for regulation that can counteract this negative development can be observed in the European Union.

The adoption of Regulation 2016/679 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data (GDPR)Footnote 3 is often seen as an important early step towards enhancing consumer autonomy in data-driven markets. Indeed, the Regulation lays down a horizontal framework, consisting of principles (e.g., lawfulness, fairness, transparency, data minimization) and data subjects rights (e.g., transparency and information about processing, right of access, right to object), as well as numerous rules and obligations applying to controllers and processors. The GDPR is thus a central EU act that determines how personal data should be processed, what data subjects must know, and what can happen if the relevant rules are infringed. In contrast, it does not contain specific requirements directed at particular data-driven services or technologies.

More recently, the EU institutions took steps to complement existing rules with a more detailed framework for online platforms and AI. In late 2020 and early 2021, the European Commission put forward two legislative proposals—for a Digital Services ActFootnote 4 and for an Artificial Intelligence Act,Footnote 5 respectively. Both initiatives are directly connected to the consumer protection domain through the New Consumer Agenda, laying out a vision for the EU consumer policy from 2020 to 2025.Footnote 6 The proposed regulatory landscape is completed with the proposal for a Digital Markets Act,Footnote 7 focusing on platform competition, and the proposal for a Data Governance Act,Footnote 8 which attempts to improve the conditions for data sharing.

The aims of the ongoing reform—concerning both the mitigation of risks and the promotion of beneficial innovations—are laudable. Even so, in assessing the EU’s legislative efforts on the digital economy, we remain ambivalent. Most notably, the proposed framework looks like a missed opportunity to provide robust consumer protection. The draft AI Act does recognize important risks that AI systems may pose to the individuals affected. However, the core of the proposal lies in the framework for high-risk applications, and the key digital services provided to consumers are not qualified as such. Similarly, the proposal does not tackle economic harms, which are an important area of concern for consumers (BEUC, 2021). Aside from the high-risk framework, the proposal also specifies a number of AI practices that are altogether prohibited, but these are nonetheless defined in a highly restrictive manner (Article 5). What remain, if this is to serve as a consumer protection instrument, are some very light-touch transparency obligations about the operation of certain AI systems, e.g., those aimed at recognizing emotions (Article 52). The proposal further undertakes to support the development of human-centered AI, but proceeds from a narrow understanding of the associated public interest (Article 54(1)(a)).

The deficiencies sketched out above are hardly addressed by the other parts of the discussed reform, including those that explicitly engage with online platforms. Admittedly, the proposed Digital Services Act sheds light on several important matters in the digital consumer markets, such as liability, content moderation, and alternative dispute resolution. However, the proposal is also far from being comprehensive and, among others, fails to adequately engage with both the risks and the potential which AI holds in the platform domain. If at all, the two issues are only covered indirectly, in the context of so-called systemic risks. More specifically, the proposal envisages an obligation for very large online platforms to identify, analyse, assess, and mitigate significant systemic risks stemming from the functioning and use made of their services in the EU (Articles 26 and 27). To improve platform scrutiny, very large online platforms would further be required to provide vetted researchers with access to their data, which, however, remains equally tied to the concept of systemic risks (Article 31(2)). Such an approach seems overly restrictive, especially since the types of risks that are explicitly mentioned in the proposal are geared primarily towards third-party actions, such as the dissemination of illegal content. Problematic practices taken at platforms’ own initiative, such as the data-driven behavioural influence (Helberger et al., 2021), as well as other contexts in which access to data for research purposes could contribute to consumer well-being, appear to go unnoticed.

Horizontal Instruments of Consumer Protection

(Un)Fairness in B2C Relationships

The increase in regulatory activities in the field of online platforms and AI observed in recent years should not be taken to imply that digital traders have been operating in a legal void. On the contrary, existing horizontal instruments—including, but not limited to the GDPR—do engage with many universal questions that can be relevant to digital consumer markets. This is especially the case for the questions of fairness in consumer contracts and in commercial practices, which have long been subject to the harmonized consumer rules.

Across the academic discussion on fairness and good faith in consumer contracts, Chris Willett identifies the following areas of analysis: the manner in which the precontractual negotiating stage is conducted, including the ability to give informed consent (so-called procedural fairness); the actual terms of the contract that is being entered into, where under scrutiny is fairness in the allocation of rights and obligations (substantive fairness); and the rules for interpreting contracts and filling gaps in them, as well as on performance and changes in the contractual relationship, and the remedies provided for by the law in the event of breach of contract (Willett, 2017). Many of these areas are currently covered under harmonised EU measures, including in the context of validating standard terms, as discussed in the following section.

In today’s economic reality, the aforementioned areas where fairness becomes an issue are a cause for concern, more so in some situations that in others. This is particularly apparent in the case of online consumer contracts, where a business provider offers its standard terms in “clickwrap” form and the consumer is impatient to click on “I agree” and gain access to a website or get to using an app. From a consumer perspective, as with every standard-form contract, when entering into a new relationship with an online service provider, most of these issues may move to the background, and the question of fairness is largely reduced to the manner in which the rules and obligations of the parties are framed and described, that is, the issue in the foreground becomes about the actual transparency of the terms and the substance of the contract.

Standard-form contracts clearly have considerable economic advantages, in that traders rely on them in an effort to cover the full gamut of contractual relationships, often building on their experience in attempting to account for circumstances and eventualities which may occur in the future, thus reducing transaction costs (Beale, 1989; Willett, 2017). On the other hand, it is no secret that this type of contract leaves little room for negotiation, and the consumer’s contractual freedom is limited to either accepting or rejecting the entire contract as written. The service provider, on the other hand, enjoys considerable advantage in being able to meticulously craft the terms of the contract in fine detail and may take as much time to do so as is needed. In a time when nearly every website, application, and device with a screen comes with its own terms of service, the time factor becomes increasingly relevant given the sheer volume of contracts that today’s consumer is asked to enter into. This is perhaps the best indicator that there is always a risk of significant imbalance between the relative powers of the parties, suggesting the need for intervention by the legislator. Existing horizontal rules on unfair terms in consumer contracts are aimed precisely at narrowing or levelling this imbalance.

The Unfair Contract Terms Directive

In the EU, the provisions on reviewing the fairness of not individually negotiated terms in B2C relationships are harmonised as part of Council Directive 93/13/EEC on unfair terms in consumer contracts (UCTD).Footnote 9 The act sets forth the minimum standard of consumer protection with regard to contract terms drafted unilaterally by the stronger party, a standard that Member States may choose to further upgrade under national law.Footnote 10 Under the UCTD, a general framework for identifying unfair terms in consumer contracts is established, asking whether, contrary to the requirement of good faith, a contested term causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations, to the detriment of the consumer (Article 3(1)). Pursuant to Article 6(1) and Recital 21 of the Directive, Member States are required to ensure that the unfairness of terms renders them nonbinding on the consumer, while not generally voiding the contract itself. According to the relevant case law of the Court of Justice (CJEU), the assessment of an unfair nature of the term involves comparing it against the relevant statutory provisions of the Member State in question that would apply in its absence.Footnote 11 Also potentially having a bearing on unfairness is the non-transparency of the terms at issue, including phrasing which does not give the consumer an opportunity to foresee the economic consequences of the contract.Footnote 12

A non-exhaustive “grey” list of potentially unfair terms has been provided in the annex to the UCTD to illustrate and exemplify terms which may be deemed unfair under framework being analysed. Thus far, no “blacklist” of terms which are always unfair has been provided at the EU level, even though corresponding recommendations have been made in the scholarship (Loos & Luzak, 2021). However, the existing grey list, developed through case law and legal research, already provides a helpful indication of which terms in consumer contracts should be approached with a wary eye. With respect to contracts entered into with digital services providers, terms relating to matters such as exclusion of liability, unilateral change, and contract termination, as well as choice of a foreign jurisdiction and foreign law, have been identified as especially problematic (Loos & Luzak, 2016; Wauters et al., 2014). As was previously indicated, similar problems also remain in the spotlight in the ongoing regulatory debate, carried out in the context of the proposed Digital Services Act.

AI for Consumer Protection

Digital Technologies and the Countervailing Power of Civil Society

In the AI and big data era, regulation and public enforcement may be insufficient, on their own, to ensure a high level of consumer protection. Therefore, scholars and consumer rights activists have argued that a new countervailing power (Galbraith, 1993) of civil society is needed to detect abuses, inform the public, and activate enforcement (Lippi et al., 2020). In the digital age, an effective countermovement also needs to be data-driven. A few examples of citizen-empowering technologies are already with us, as in the case of ad-blocking systems, as well as more traditional anti-spam software and anti-phishing techniques. But such efforts need to be taken to the next level. On the consumer’s side, support services can be deployed with the goal of analysing massive amounts of information made available to them and providing help in understanding this information and making a legal assessment. In the last few years, several projects and tools have been developed with these goals in mind. Notable examples include summary generators, analytical tools assessing the use of personal data, consumer-educating tools, and ontologies (Pałka & Lippi, 2019). In consumer law, significant progress has been made towards automating the task of identifying potentially unfair and unlawful clauses in online contracts and privacy policies, often violating the relevant EU acts. This is part of the CLAUDETTE project.

Introducing CLAUDETTE: An Automated Unfairness Detection Tool

The CLAUDETTE projectFootnote 13 aims at providing support to consumers and nongovernmental organisations for the analysis of consumer contracts and privacy policies. This support is provided by automatically identifying potentially and clearly unfair and unlawful clauses (Contissa et al., 2018b; Lippi et al., 2019). The CLAUDETTE system is based on machine learning, and in particular on supervised learning methods. Thus, in order to train the machine learning classifier, the system has been provided with a source corpus, containing examples of fair, potentially unfair, and clearly unfair clauses, as detailed in the following.

The ToS Corpus With regard to the analysis of consumer contracts, the source corpus contains 100 terms of service (ToS), analysed and manually annotated by legal experts in Extensible Markup Language (XML). The documents were selected among those offered by some of the major players in terms of user base, global relevance, and time the service was established. The marked-up clauses in the training set were used to indicate to CLAUDETTE how certain legal qualifications correspond to certain textual forms, giving the system an input, it needs to determine the category to which the clause belongs and assess its unfairness. The training algorithms “teach” the system to make determinations and assessments similar to those specified in the training set. Thus, these algorithms provide the system with criteria and mechanisms for classifying clauses. We could say that the system, through training, generates its own concept of unfairness, which is then applied to the task of classifying new clauses.

Eight categories of (potentially) unfair clauses have been identified based on the current legislative framework. In particular, they establish (1) jurisdiction in a country different from that of a consumer’s residence (<j>); (2) the choice of a foreign law (<law>); (3) liability limitations (<ltd>); (4) the provider’s right to unilaterally terminate the contract or access to the service (<ter>); (5) the provider’s right to unilaterally modify the contract or service (<ch>); (6) mandatory arbitration before court proceedings can commence (<a>); (7) the provider’s right to unilaterally remove consumer content (<cr>); and (8) consumer consent to the agreement simply by using a service, downloading an app, or visiting a website (<use>). More recently, we identified an additional category of potentially unfair clauses, i.e., clauses stating (or implicitly assuming) that (9) the scope of consent granted to the ToS also takes in the privacy policy, which forms part of the “General Agreement” (<pinc>). Such categories are widely used in ToS for online platforms (Dari-Mattiacci & Marotta-Wurgler, 2018; Loos & Luzak, 2016; Lippi et al., 2019; Micklitz et al., 2017). To capture the different degrees of (un)fairness we appended a numeric value to each XML tag, with 1 meaning “clearly fair,” 2 “potentially unfair,” and 3 “clearly unfair,” according to the criteria set out in Lippi et al. (2019). For instance, the <ltd3> label indicates that the clause concerns the provider’s limitation of liability and that it has been considered clearly unfair.

Concerning the new <pinc> category, it is interesting to note that such clauses have been introduced in ToS during the weeks right before and after 25 May 2018, i.e., the day on which the GDPR went into effect. These clauses have always been considered potentially unfair. As an example, consider the combination of the following clauses, taken from the DeviantArt ToS (last update not available):

By using our Service, you agree to be bound by Section I of these Terms (“General Terms”), which contains provisions applicable to all users of our Service, including visitors to the DeviantArt website (the “Site”). [...] The terms of DeviantArt’s privacy policy are incorporated into, and form a part of, these Terms.

While the first clause has been tagged as <ch2>, the second one has been labeled as <pinc2>. As emerges from the combined reading of the above clauses, by implicitly agreeing to the ToS, the consumer also agrees to the processing of personal data as explained in the Privacy Policy.

The Machine Learning Methodology The automated detection of (potentially) unfair clauses was addressed focusing on two main tasks: (a) detecting unfair clauses, so as to assess whether each clause is fair or (potentially) unfair; and (b) classifying unfair clauses, so as to determine the category an unfair clause belongs to (jurisdiction, arbitration, etc.).

The problem of detecting potentially unfair contract clauses was approached as a sentence classification task by adopting two methods. The first one consists in treating sentences independently of one another (sentence-wide classification), while the second one takes into account the document’s structure, and in particular the sequence of sentences. For each of these two methods, different classifiers have been tested and the results obtained were subjected to a comparative analysis (Lippi et al., 2019). The sentences obtained from the segmentation of the ToS texts were subjected to a lexical analysis (tokenization) and a syntactic analysis (parsing), using Stanford CoreNLP.Footnote 14 In order to process the lexical content and the grammatical structure of sentences, we used different machine learning algorithms that include the bag-of-words and tree kernels (Lippi et al., 2019). The first captures the lexical differences between sentences and represents each sentence as a vector of the lexicon within the sentence concerned. The second, i.e., the tree kernels algorithm, analyses similarities and differences between the grammatical structures of sentences.

We ran experiments on the annotated corpus following the leave-one-document-out procedure, in which each document, in turn, is excluded from the training set and used to test and validate the classifier’s performance. In this way, for each document, the system generates predictions and also measures its performance with regard to the ToS at issue. This is a standard procedure in machine learning, making it possible to assess our system’s generalization capabilities. The results of the experiments show that CLAUDETTE correctly detected around 80% of the potentially unfair clauses in each category, ranging from a minimum 72.7% in the case of arbitration clauses, up to 89.7% in the case of jurisdiction clauses.

The proposed approach was implemented and developed as a Web server, reachable at the address http://claudette.eui.eu/demo, so as to produce a prototype system that users can easily access and test. They can simply paste the text to be analysed and subject it to the CLAUDETTE evaluation. The system will then produce an output file that highlights the sentences predicted as containing potentially unfair clauses, as well as the category they belong to. More recently, the CLAUDETTE team developed a new functionality aimed at providing users with explanations, and in particular legal rationales—i.e., the reasons why a clause is considered unfair—and the associated confidence score (Ruggeri et al., 2021).

Aside from developing CLAUDETTE’s prediction capacities, the implementation of the project, including the labelling of a comparably wide sample of standard terms in use, has also generated valuable insights about B2C relationships in digital markets. In the following, we provide a picture of the contractual practices of digital traders through statistical analysis and elaborate on the existing and potential issues faced by consumers in online environments.

Unfair Practices in Digital Markets: The Terms of Service Landscape

This section provides a longitudinal and comprehensive analysis of potentially unfair clauses in contractual terms of service used by international digital service providers. It discusses the results of an empirical study conducted on the CLAUDETTE dataset and the conclusions that can be drawn from this study. As mentioned above, the dataset consists of 100 ToS, available on the providers’ websites for review by potential and current consumers. Since 2017, the analysed ToS were gradually downloaded and analysed over a period of 3 years, with some follow-up review for the same services. It is the intention of the CLAUDETTE project researchers to increase the dataset and to undertake further reviews so as to monitor changes and identify any new patterns that may emerge in the ToS landscape, particularly as the regulatory framework evolves (Jabłonowska et al., 2021).

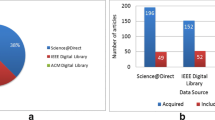

For the purpose of this study, we grouped contracts of online service providers into nine market sectors, as detailed in Table 1, in order to assess the relevant terms that allocate rights, obligations, and risks between both parties. This classification is also meant to investigate the distribution of specific (potentially) unfair contract-making practices along the mentioned sectors, as well as common patterns and correlations among them. The division of documents into groups is unbalanced: 20 in gaming and entertainment; 17 in social networks and online dating; 14 in travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries; 11 in content-sharing platforms; 10 in productivity tools and business management; eight in both e-commerce and Web search and analytics; seven in health and well-being, and five in communication tools. To account for this imbalance, the subsequent sectoral analysis refers to the proportion of documents that contain a given type of practice in a given sector.

To paint the terms of service landscape in the studied sectors, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the dataset and created a novel structured corpus of different (potentially) unfair contracting practices. At the same time, we narrowed down our focus to the following five categories: (i) liability exclusions and limitations (ltd); (ii) unilateral changes (ch); (iii) unilateral termination (ter); (iv) content removal (cr); and (v) arbitration (a). In particular, we selected the five most challenging types of clauses, excluding the remaining four categories, which are less interesting for the purposes of this work, as they are always associated with the same types of practices and rationales.

Interestingly, of the 21,063 sentences in the corpus, 2346 (11.1%) were labeled as containing a potentially or clearly unfair clause, thus confirming the importance and the potential impact of the analytical work we carried out. The distribution of the different categories across the 100 documents is reported in Table 2 (Ruggeri et al., 2021). We observed a high frequency of some of the selected categories within the dataset. Arbitration clauses are the most uncommon, being contained in only 43 documents. All the other categories appear in at least 83 out of 100 documents. Limitation of liability and unilateral termination together account for more than half of all the potentially unfair clauses.

In the following, we discuss whether and to what extent it is possible to retrieve diverse (potentially) unfair practices within each unfair-clause category, as well as whether and to what extent certain practices are more frequent than others in specific market sectors and characterize each such sector. To conduct this analysis, we assigned an identifier (ID) to each (potentially) unfair practice. Each clause in the CLAUDETTE dataset has been indexed with one or more relevant IDs, thus creating a one-to-many mapping of clauses to practices, as detailed in the following sections. The identified unfair practices have been also used to create a corpus of legal rationales or bases, i.e., reasons why a clause is (potentially) unfair (Ruggeri et al., 2021).

Liability Exclusions and Limitations

Service providers often dedicate a considerable portion of their ToS to disclaiming and limiting liabilities. Most of the circumstances under which these limitations are declared significantly affect the balance between the parties’ rights and obligations. This makes them at least questionable under the UCTD. In particular, we identified six classes of clauses limiting and/or excluding liability for damages. We thus have limitations/exclusions by (i) liability theory; (ii) causal link; (iii) kind of damages; (iv) standard of care; (v) cause; and (vi) compensation amount, as shown in Figure 1.

Within each class, we distinguished a variety of potentially unfair practices, mapping different questionable circumstances under which ToS reduce or exclude the provider’s liability (Table 3). As noted above, these practices correspond to a set of legal rationales for unfairness (Ruggeri et al., 2021). Two out of 18 are labelled clearly unfair practices (i.e,. injury and grossnegligence), while 14 have been evaluated as potentially unfair.

As noted, each (potentially) unfair ltd clause within the dataset may be relevant, and thus indexed with the corresponding (IDs), under more than one class and (potentially) unfair practice. Note that, even though the majority of rationales refers to the exclusion of claims for compensation, they cover different aspects at stake. Consider for instance anyloss and anydamage. While in the first case the liability exclusion depends on the causal link with the damage (e.g., incidental, direct, indirect, punitive damages), in the second case the limitation concerns the type of loss suffered by the consumer (e.g., economical, reputational).

As an example, consider the following clause taken from the Box ToS (updated August 2017):

To the extent not prohibited by law, in no event will Box, its affiliates re-sellers, officers, employees, agents, suppliers or licensors be liable for: any direct, incidental, special, punitive, cover or consequential damages (including, without limitation, damages for lost profits, revenue, goodwill, use or content) however caused, under any theory of liability, including, without limitation, contract, tort, warranty, negligence or otherwise, even if Box has been advised as to the possibility of such damages. (IDs: extent, anydamage, reputation, dataloss, ecoloss, awareness, liabtheories).

This clause can also be found in the current Box ToS version updated on August 2021. It limits the provider’s liability by kind, i.e., broad category of losses (e.g., loss of data, economic loss, and loss of reputation); by standard of care, since it states that the provider will never be liable even if negligent and aware of the possibility of damages; and by causal link (e.g., special, incidental, and consequential damages), as well as by any liability theory.

Figure 2 presents the recurrence of each (potentially) unfair ltd practice within the dataset, i.e., relative to the 100 analysed ToS. In particular, we identified 1595 references to 18 (potentially) unfair practices in 629 ltd clauses. The most common practice concerns general and nonspecific limitation and/or exclusion of liability (19.62%), followed by liability limitation for the actions of third parties (11.60%), for any damage (9.28%), and for interruption and/or the unavailability of the service (8.15%). Among the less frequent, by contrast, are limitations relating to cases of gross negligence (0.19%), intentional offences and/or damages, and physical and personal injuries (1.08%).

Figure 3 presents the distribution of each practice across market sectors. Since the division of documents is unbalanced (see Section 4), we have normalized the number of each practice within each sector. In the following, we present a detailed description of each class of (potentially) unfair ltd clauses, and an analysis of the related practices across markets.

Limitation of Liability by Legal Theory

The first class of clauses restricts the theories of liability (ID: liabtheories) on which consumers can base actions against service providers. We retrieved this kind of limitation 53 times within the dataset (see Fig. 2), across all the sectors studied. Moreover, as shown in Figure 3, this kind of disclaimer is very frequent in ToS for communication tools (the 80% of ToS), being 2.8 times more frequent than in travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries (28.5% of ToS); 2.2 times more frequent than in content-sharing platforms (36.3% of ToS); and 1.9 times more frequent than in social networking and dating services (41.1% of ToS). In particular, while in the former, four out of five documents contain on average two LTD clauses by legal theory, in travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries only four out of 14 ToS contain a clause of this kind. In the latter case, i.e., social networks and dating, we retrieved such a practice only eight times in seven out of 17 ToS. The distribution in e-commerce, Web search and analytics services, and games and entertainment is more or less equivalent, amounting respectively to five clauses in four out of eight contracts; four clauses in four out of eight ToS; and 13 clauses in 11 out of 20 ToS. These clauses create an imbalance in the parties’ rights, in particular where the provider waives all types of damages under all theories. In this case, consumers will have greater difficulty in exercising their rights effectively. As an example, consider the following clause from the Airbnb terms of service (updated on June 2017):

Neither Airbnb nor any other party involved in creating, producing, or delivering the Airbnb Platform or Collective Content will be liable for any incidental, special, exemplary or consequential damages, including lost profits, loss of data or loss of goodwill, service interruption, computer damage or system failure or the cost of substitute products or services, or for any damages for personal or bodily injury or emotional distress [...] whether based on warranty, contract, tort (including negligence), product liability or any other legal theory, and whether or not Airbnb has been informed of the possibility of such damage, even if a limited remedy set forth herein is found to have failed of its essential purpose. (IDs: thirdparty, injury, anydamage, anyloss, ecoloss, dataloss, reputation, discontinuance, compharm, liabtheories).

The clause above can also be found in the current Airbnb ToS, last updated on 30 October 2020. It can clearly be appreciated that this clause (and others like it) is relevant under multiple classes of (potentially) unfair ltd clauses. Indeed, it limits the potential provider’s liability by theory, as well as by kind of damages, namely, for personal injuries and broad categories of loss (e.g., loss of data, loss of reputation, and economic loss), and by cause (e.g., service interruption, computer damage, and third-party actions). Under this kind of practice, recovering damages from the trader will be particularly difficult. Consider, for instance, a case in which a product defect is caused a property damage. In theory, a consumer should be able to bring an action in tort. However, clauses waiving all types of damages under any liability theory, whether contract, tort, or other kind, will pose a significant barrier to the pursuit of consumer claims. Even when the exclusion concerns only certain liability theories, a clause may still not measure up to the UCTD fairness test. For example, in view of the recent adoption of Directive 2019/770 on certain aspects concerning contracts for the supply of digital content and digital services (Digital Content Directive),Footnote 15 far-reaching exclusions of the trader’s contractual liability for the digital content and digital services provided seem more than questionable.

Limitation of Liability by Causal Link

The second class of (potentially) unfair limitation of liability concerns the causal link with potential damages (ID: anydamage). In particular, the service provider limits the liability by disclaiming broad categories of damages, often encompassing special, direct and/or indirect, punitive, incidental, or consequential damages. Notably, within the dataset, this kind of limitation occurs 148 times (see Fig. 2) across all the analysed market sectors. As shown in Figure 3, clauses limiting the provider’s liability for any damage are present in 100% of ToS in four out of nine sectors, i.e., productivity tools and business management, Web search and analytics, communication tools, and content-sharing platforms. Conversely, their occurrence is lower in the travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries sector, being present only in four out of 14 ToS. As an example, consider the following clause taken from the Expedia terms of service (updated on February 2018):

In no event shall the Expedia Companies, the Expedia Partners and/or their respective suppliers be liable for any direct, indirect, punitive, incidental, special or consequential damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, your access to, display of or use of this Website or with the delay or inability to access, display or use this Website (including, but not limited to, your reliance upon opinions appearing on this Website; any computer viruses, information, software, linked sites, products and services obtaining through this Website; or otherwise arising out of the access to, display of or use of this Website) whether based on a theory of negligence, contract, tort, strict liability, consumer protection statutes, or otherwise, and even if the Expedia Companies, the Expedia Partners and/or their respective suppliers have been advised of the possibility of such damages. (IDs: anydamage, compharm, contractfailure, awareness, liabtheories, discontinuance).

This clause is also present in the current Expedia ToS, last updated in October 2020. Clauses excluding liability by causal link are clearly meant to limit the consumers’ ability to recover damages. They may be found unfair particularly when read in combination with the limitation of liability deriving from certain specific causes, such as breach of agreement and failures of performance, as well as whenever they are not based on force majeure, a case in point being terms seeking to exclude direct liability, as in the above example. Additionally, this clause unfairly does not distinguish between damages caused through the service provider’s fault or negligence and those caused as a result of circumstances beyond the provider’s sphere of control. Such limitations may also be found unfair, particularly when read in conjunction with clauses stating that the service is provided as is and on an as available basis (Bradshaw et al., 2011; Loos & Luzak, 2016), which clauses are meant to exclude express or implied warranties that the service provided will be fit for purpose or merchantable.

Limitation of Liability by Kind of Damage

The third class pertains the kind of damage for which liability is limited and/or excluded. Under this class, service providers usually differentiate between losses and injuries. With regard to losses, it is possible to further distinguish between clauses disclaiming the provider’s liability for (a) broad categories of loss—even if referring to certain specific objects, such as economic loss (ID: ecoloss), loss of reputation (ID: reputation), and loss of data (ID: dataloss)—and those limiting the liability for (b) any kind of loss (ID: anyloss) resulting from the use of the website and related services. These liability limitations affect all the analysed sectors. Specifically, limitation of liability for economic losses usually includes cases of loss of profits, loss of income, lost opportunity, lost business and sales, and loss of revenue. We retrieved 69 occurrences within the dataset (see Fig. 2). From a sectoral perspective, they are highest in Web search and analytics—where 87.5% of ToS contain this type of limitation—followed by content-sharing platforms, productivity tools and business management, and communication tools. In contrast, the occurrence is lower in the travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries sector, where only 14.29% of contracts contain a clause of this kind.

Loss of reputation refers to both reputation and goodwill damages, and it amounts to a total of 39 occurrences (see Fig. 2). This kind of disclaimer appears in 72.7% of ToS in the content-sharing platforms domain, followed by Web search and analytics (50% of ToS), health and well-being (42.8% of ToS), and social networks and dating (41.1% of ToS). In contrast, it is quite rare in the travel accommodation and service intermediaries sector (14.2% of ToS) and in games and entertainment (15% of ToS).

Clauses meant to limit or exclude providers’ liability with regard to data preservation usually include diverse sets of circumstances, such as disclosure, damage, destruction, or data corruption, failure to store data, or loss of data and other digital materials. We found a total of 74 clauses of this kind (see Fig. 2), mostly present in productivity tools and business management (100% of ToS) and in content-sharing platforms (90.9% of ToS). In contrast, such a practice is unsurprisingly very low in the travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries sector (7.1% of ToS).

Finally, we found 122 clauses disclaiming the provider’s liability for any kind of loss (see Fig. 2). They are more frequent in the productivity tools and business management sector (100% of ToS), followed by e-commerce (87.5% of ToS) and Web search and analytics (87.5% of ToS), and lowest in travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries (28.5% of ToS).

As an example, consider the following clauses, taken from the WeTransfer (updated on 9 October 2017) and the BetterPoints (retrieved in May 2019) ToS, respectively:

You acknowledge and agree that WeTransfer is not responsible for any damages to your computer system or the computer system of any third party that result from use of the Services and is not responsible for any failure of the Services to store, transfer or delete a file or for the corruption or loss of any data, information or content contained in a file. (IDs: compharm, dataloss, content).

We expressly exclude, to the fullest extent permitted by law, all liability of betterpoints.uk, its directors, employees or other representatives, howsoever arising, for any loss suffered as a result of your use of this website or involvement in any way with betterpoints.uk. (IDs: extent, anyloss).

The reported clauses are both present in the current WeTransfer and BetterPoints ToS, retrieved in December 2021 and last updated on 15 April 2021, respectively. The analysis of the entire dataset has shown that the limitation or exclusion of liability for failures in data preservation is usually linked to suspension, discontinuance, lack of availability, and termination of service. In contrast, failures to preserve data integrity are linked to (a) electronic virus attacks and malware and (b) security breaches. With regard to data preservation, an important issue pertains to cases where the unilateral suspension and/or termination of the service would entail losing some digital content (e.g., purchased and/or stored content, purchased apps, email address), or, on the contrary, where there would be an opportunity for consumers to gain access to the data to retrieve it for use and storage elsewhere. In the first case, clauses limiting the service provider’s liability appear, in our opinion, to be disproportionately disadvantageous to the consumer and thus unfair. Concerning the data integrity, significantly, the exclusion of liability for damage seems to be frequently imposed by providers that, given the nature of their service (e.g., storage-and-backup-service providers and file-transfer services, such as Dropbox and WeTransfer), should guarantee appropriate measures for data integrity. With regard to injuries, Annex I, paragraph 1(a) UCTD explicitly mentions as unfair clauses that limit or exclude the seller’s or supplier’s liability in the event of the death of a consumer or personal injury to the latter resulting from an act or omission of that seller or supplier. As an example, consider the following clause taken from the Academia terms of service (last updated on May 2017):

Neither Academia.edu nor any other person or entity involved in creating, producing, or delivering the site, services or collective content will be liable for any incidental, special, exemplary or consequential damages, or lost profits, loss of data or loss of goodwill, service interruption, computer damage or system failure or the cost of substitute products or services, or for any damages for personal or bodily injury or emotional distress arising out of or in connection with these terms or from the use of or inability to use the site, services or collective content, or from any communications, interactions or meetings with other users of the site or services or other persons with whom you communicate or interact as a result of your use of the site or services, whether based on warranty, contract, tort (including negligence), product liability or any other legal theory, whether or not Academia.edu has been informed of the possibility of such damage, and whether or not foreseeable, even if a limited remedy set forth herein is found to have failed of its essential purpose. (IDs: injury, anydamage, compharm, anyloss, dataloss, reputation, liabtheories, ecoloss, discontinuance).

Even though, at first glance, it may be difficult to imagine a situation where an act or omission of an online service provider leads to a consumer’s death, it is conceivable to foresee cases where some people may be significantly emotionally or psychologically disturbed if their online services were blocked or disrupted, as in cases where certain digital data (e.g., pictures, work-related files, or research data) are erased. Additionally, the above clause also excludes the provider’s liability under any legal theory; by different classes of causes, such as service interruption; by causal link; and by the standard of care (as detailed in the following), including cases of negligence, foreseeability, and awareness of the damage. Finally, as digital services become increasingly connected to offline interactions, e.g., in the context of online-to-offline commerce or the Internet of Things, the prospect of personal injury or even death in connection to use of a service seems no longer so remote.

Limitation of Liability by Cause

A further class of (potentially) unfair limitations of liability concerns the cause of damage. Under this class, we identified as potentially unfair clauses that limit liability for damage deriving from (a) failure to perform one or more contractual obligations under the terms of service (ID: contractfailure); (b) actions by third parties (ID: thirdparty; (c) a security breach (ID: security); (d) service interruption and unavailability (ID: discontinuance); (e) virus, malware, etc., causing harm to hardware and software (ID: compharm); and (f) information published, stored, and processed within the services (ID: content).

Breach of Agreement and Failure to Perform Contractual Obligations Under the hypothesis concerning a trader’s failure to fulfil one or more of its obligations, potentially unfair clauses stipulate that the service provider will not be liable for any failure to perform a contract or fulfil its terms obligations, including in cases involving breach of agreement, lack of performance, and failures to deliver products and services (ID: contractfailure). This kind of limitation appears in 25 clauses within the dataset (see Fig. 2), affecting 8 out of 9 sectors. It is most frequent in the e-commerce sector, being present in 50% of ToS, followed by games and entertainment, where 30% of ToS contain this practice. In contrast, occurrence is lowest in productivity and business management tools, with only 10% of ToS being affected (see Fig. 3).

As examples, consider the following clauses, taken from the Courchsurfing (updated on 10 September 2018), Goodreads (updated on 6 December 2017), and the Zynga terms of service (updated on 26 July 2016), respectively:

We shall not be liable for any failure or delay in performing under these terms, whether or not such failure or delay is due to causes beyond our reasonable control. (IDs: contractfailure).

You agree that Goodreads will not be liable to you for any interruption of the Service, delay or failure to perform. (IDs: discontinuance, contractfailure).

To the fullest extent allowed by any law that applies, the disclaimers of liability in these terms apply to all damages or injury caused by the service, or related to use of, or inability to use, the service, under any cause of action in any jurisdiction, including, without limitation, actions for breach of warranty, breach of contract or tort (including negligence). (IDs: extent, anydamage, injury, contractfailure, liabtheories).

All the above clauses are still present in the current Couchsurfing, Goodreads, and Zynga ToS, last updated in June 2020, April 2021, and November 2021, respectively. These clauses are meant to limit and/or exclude the guarantees related to the provision of the service and its reliability. Although, there might be circumstances under which such failures fall outside the service provider’s sphere of control, in most cases they do not distinguish between unforeseeable problems and those caused by the provider’s fault or negligence. Indeed, in some cases, as in the clause above, the limitation and/or exclusion of liability also expressly covers cases where the failure is due to the provider’s negligence or to a cause within the provider’s sphere of control. Therefore, these limitation-of-liability clauses seem to indirectly state that consumers could not reasonably expect the service to be delivered without problems. In this regard, it has been noted that when consumers are affected by a breach of contract, this may have the capacity to unsettle lives beyond the pocketbook (Willett, 2016). As a consequence, consumers must deal with disruption in their private lives. The recently adopted Digital Content Directive recognizes the asymmetrical nature of business-to-consumer contracts for the supply of digital content and digital services and lays down both subjective and objective conformity criteria in respect of such contracts (Articles 7 and 8). Accordingly, broad exclusions of traders’ liability for breach of contract and for failure to perform contractual obligations, which could lead consumers into error about their legal situation, would likely be deemed unlawful.

Service Interruption and Unavailability Clauses falling under this hypothesis usually state that the service provider will not be liable under one or more of the following circumstances: any technical problem, failure, or inability to use the service; suspension, disruption, modification, discontinuance, unavailability of service, even when due to any unilateral change, unilateral termination, unilateral limitation on certain features and services, or restriction on access to the service,Footnote 16 without notice (ID: discontinuance). This limitation has been retrieved in 130 clauses across the entire dataset (see Fig. 2) and across all the sectors studied. It is most present in the content-sharing platform sector, with 100% of contracts containing such clauses, as well as in health and well-being, where the affected ToS amount to 85.7%. In contrast, only 21% of ToS in the travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries sector disclaim liabilities for service interruption and/or unavailability (see Fig. 3).

As examples, consider the following clauses, taken from the BetterPoints (retrieved in May 2019) and Lindenlab (last updated on 31 July 2017) ToS, respectively:

You acknowledge that we are not responsible for suspension of the Service, regardless of the cause of the interruption or suspension. (IDs: discontinuance).

Likewise, except as set forth above, in any Additional Terms, or as required by applicable law, Linden Lab is not responsible for repairing, replacing or restoring access to your Usage Subscription, or Virtual Goods and Services (including any Virtual Space or other Virtual Tender associated with each Product, as further described in an applicable Product Policy), or providing you with any credit or refund or any other sum, in the event of: (a) Linden Lab’s change, suspension or termination of any Usage Subscription or Virtual Goods and Services (including any Virtual Space or other Virtual Tender associated with each Product, as further described in an applicable Product Policy); or (b) for loss or damage due to Website or Server error, or any other reason.[...]In such event, you will not be entitled to compensation for such suspension or termination, and you acknowledge that Linden Lab will have no liability to you in connection with such suspension or termination. (IDs: dicontinunance, anyloss, anydamage).

The BetterPoints ToS were last updated in April 2021, and the above clause is still present, while the Lindenlab ToS have never been updated. Similarly to the case of liability limitation for breach of contract, these clauses seem to exclude the provider’s liability for disruptions in the availability and reliability of the service, excluding any guarantees with regard to its provision. Limitation-of-liability clauses for service interruption and unavailability may substantially affect consumers’ interests, likewise giving rise to an imbalance in contractual rights and obligations to the detriment of consumers.

Security Breach, Electronic Viruses, and Other Destructive Program Attacks Often, limitation-of-liability clauses restrict or exclude the provider’s liability for any damage deriving from a security breach, including any unauthorised access, alteration, or modification of data and data transmission (ID: security). In the dataset, such clauses are 21 in total (see Fig. 2). They were found in eight out of nine sectors, with the highest occurrence in the Web search and analytics sector (37.5% of ToS), and the lowest in the travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries sector (7.1% of ToS). These clauses are completely absent in gaming-and-entertainment ToS. Similarly, online service providers frequently limit their liability for any harm or damage to hardware and software or other equipment or technology, including data, due to virus attacks, malware, worms, Trojan horses, or any similar contamination or destructive program (ID: compharm). We found a total of 27 clauses (see Fig. 2) in eight out of nine sectors. They are mostly present in productivity tools and business management (50% of ToS) and in health and well-being (42.8% of ToS). The least-affected sector seems to be gaming and entertainment, where only 5% of ToS contained such clauses, while they were completely absent in Web search and analytics contracts. In our opinion, a full exclusion or broad limitation of liability can be seen as unjustified and significantly tilting the balance between the parties’ rights and obligations, and therefore be (potentially) unfair, regardless of whether the damage was caused intentionally or through negligent or grossly negligent behaviour, regardless of whether the attack was foreseeable by the service provider or whether the service provider was made aware of the possibility of an attack, as well as regardless of whether the service provider took the necessary security measures. Consider, for instance, the following examples, taken from the Myspace (last updated on 24 May 2018) and Badoo (updated on 11 September 2018) ToS, respectively:

In no event shall Myspace be liable to you or any third party for any indirect, consequential, exemplary, incidental, special or punitive damages, including without limitation, lost profit damages arising from [...] or any damage to a user’s computer, hardware, software, modem, or other equipment or technology, including damage from any security breach or from any virus, bugs, tampering, fraud, error, omission [...], including losses or damages in the form of lost profits, or equipment failure or malfunction, even if my space has been advised of the possibility of such damages. (IDs: anydamage, thirdparty, compharm, discontinuance, reputation, dataloss, awareness, content, ecoloss).

Badoo is not responsible for any damage to your computer hardware, computer software, or other equipment or technology including, but without limitation damage from any security breach or from any virus, bugs, tampering, fraud, error, omission, interruption, defect, delay in operation or transmission, computer line or network failure or any other technical or other malfunction. [...] This limitation on liability applies to, but is not limited to, the transmission of any disabling device or virus that may infect your equipment, failure or mechanical or electrical equipment or communication lines, telephone or other interconnect problems (e.g., you cannot access your internet service provider), unauthorized access, theft, bodily injury, property damage, operator errors, strikes or other labor problems or any act of god in connection with Badoo including, without limitation, any liability for loss of revenue or income, loss of profits or contracts, loss of business, loss of anticipated savings, loss of goodwill, loss of data, wasted management or office time and any other loss or damage of any kind, however arising and whether caused by tort (including, but not limited to, negligence), breach of contract or otherwise, even if foreseeable whether arising directly or indirectly. (IDs: security, injury, anydamage, anyloss, reputation, contractfailure, awareness, dataloss, liabtheories, ecoloss).

These two clauses are both present in the current versions of the MySpace and Badoo ToS. The latter were last updated in March 2021.

As in case of limitation of liability for service interruption and unavailability, such clauses are meant to exclude the security and reliability of the service. As the size of e-commerce and social media grows, security and privacy remain critical obstacles that hinder more accelerated growth of e-commerce. There have been many security-breach cases in the last decade, such as those of Target Corporation’s security and payment system (2013), eBay’s cyberattack (2014), Uber’s hacking incident (2016), Facebook’s breach of personal data use and privacy (2018), and many others. As a consequence, consumers have often suffered losses caused by Internet services not working properly, including losses due to leaks of personal data stored in cloud computing and social network platforms. The service provider’s obligation to put security measures in place in order to prevent failure in the protection of personal data, as well as the provider’s responsibility for such measures, has continually been enhanced from the Data Protection Directive (DPD)Footnote 17 to the GDPR. Although the latter is in force, service providers keep using clauses meant to limit or exclude their liability for security issues. It is also important to note that a higher incidence of this practice can be identified in the ToS for social networks and dating, as shown in Figure 2, which usually collect a large amount of personal and sensitive data.

Published Information and Content Very frequently ToS state that the provider is not liable for any content, material, or information posted, stored, or processed within the services—including in cases of inaccuracy or error, copyright violation, defamation, slander, libel, falsehood, obscenity, pornography, profanity, or any objectionable material—or for software, products, and services on the website. These clauses are 122 (see Fig. 2) and they have been considered always potentially unfair. From a sectoral perspective, such clauses were found in all the sectors studied and, more specifically in 100% of contracts in e-commerce, while least affected is the travel, accommodation, and service intermediaries sector, where only 28.5% of ToS contains this liability disclaimer. As concerns the remaining market sectors, the occurrence of this kind of limitation of liability ranges from 75% of ToS in the productivity and business management tools sector to 40% of ToS in the communication tools sector.

Under the E-Commerce Directive (ECD)Footnote 18 intermediary service providers (ISPs) should not be held liable for the content they transmit, store, or host, provided they do not have knowledge of illegal activity, as long as they are in no way involved in the information transmitted, or, in the case of hosting services, do not have any knowledge or awareness of the illegal activities, and if they do become aware of such content, they much promptly remove or disable it. Illegal content covers a wide range of violations, including infringements of intellectual property rights (trademark or copyright), child pornography, racist and xenophobic content, defamation, terrorism or violence, illegal gambling, illegal pharmaceutical offers, and illicit tobacco or alcohol advertisements. The ECD’s safe harbour framework was introduced at the turn of the century as a means for developing online services and enabling the information society to flourish (Ullrich, 2017).

Although the safe harbours adopted within the ECD remain, in principle, intact, the provider’s liability for the content they transmit, store, or host has been at the center of a big debate, and the context in which they operate is being gradually enriched through law and policy developments. Most notably, the recently adopted Directive EU 2019/790 on copyright in the Digital Single Market (DSM Directive),Footnote 19 and especially its Article 17, governing the newly created liability and licensing scheme, has been regarded as a paradigm shift in copyright law. Newly adopted rules contribute to the formation of an emerging liability regime for unlawful content that differs from the conditional liability-exemption regime envisaged within the E-Commerce Directive (Montagnani, 2019).

Aside from the DSM Directive, the responsibilities of online intermediaries with regard to published information and content have been reshaped through a revision of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD),Footnote 20 the recently adopted Regulation (EU) 2021/784 on addressing the dissemination of terrorist content online,Footnote 21 the Commission guidance on application to commercial platforms of the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive,Footnote 22 as well as many communications and recommendations dealing with the issue of illegal content online.Footnote 23 Finally, the draft Digital Services Act proposes in Article 5 further limitations on the liability exemption for host providers, including limitations where the recipient of the service is acting under the authority or control of the provider.

Overall, although liability exemptions for online intermediaries continue to be a key element of the European system, these exemptions generally are not unconditional. Moreover, further layers of duties and obligations are being gradually imposed on online platforms, under headings such as monitoring, diligence, reporting and flagging, cooperating with rightholders, forming licensing agreements, adopting appropriate measures to prevent unlawful content, and designing platforms in a way that prevents consumers from being misled. Violation of such obligations can trigger the liability of the respective providers.

Despite the legal framework and developments just described, broadly framed liability exemptions for published information and content are frequent in online terms of service. Consider the following examples, taken from the Goodreads (updated on 6 December 2017) and HeySuccess (retrieved in February 2019) ToS:

Goodreads takes no responsibility and assumes no liability for any User Content that you or any other Users or third parties post or send over the Service. You understand and acknowledge that you may be exposed to User Content that is inaccurate, offensive, indecent, or objectionable, and you agree that Goodreads shall not be liable for any damages you allege to incur as a result of such User Content. (IDs: thirdparty, content).

We will not be liable to any user for any loss or damage, whether in contract, tort (including negligence), breach of statutory duty, or otherwise, even if foreseeable or we have been informed of the possibility of such loss or damage, arising under or in connection with: use of, or inability to use, our site; any negative or defamatory comments made about you by your referee(s) or other users; use of or reliance on any content displayed on our site; or service interruption, computer damage or system failure. (IDs: anydamage, anyloss, contractfailure, awareness, discontinuance, compharm, liabtheories, dicontinuance, content).

The two clauses above are both present in the current Goodreads and HeySuccess terms of service, last updated in April 2021 and retrieved in December 2021, respectively.

Third-Party Actions As mentioned, clauses designed to limit or exclude the provider’s liability for actions by third parties are among the most frequent LTD (potentially) unfair clauses. They account for 185 clauses in the studied corpus (see Fig. 2), affecting all the market sectors considered (see Fig. 3). The highest occurrence can be found in the productivity and business management tools sector and in the communication tools sector, in both affecting 80% of the relative contracts, followed by health and well-being (71.4% of ToS) and e-commerce and Web search analytics (62.5% of ToS in both cases). In contrast, the lowest number of contracts containing limitation-of-liability clauses for third-party actions belongs to gaming and entertainment (35% of ToS).