Abstract

Over the past 30 years, there has been a surge of interest in understanding the experiences and outcomes of expectant and parenting foster youth. Despite the importance of understanding this unique population of foster youth, there remains a lack of research on fathers in foster care. Most studies of expectant and parenting foster youth focus on mothers in care, and studies that have examined fathers in care provide little insight compared to what we know about mothers. Furthermore, existing research on fathers in foster care is limited by underreporting, service engagement issues, lack of meaningful engagement data, and very little information on fathers’ involvement with their children. There is very little published research on the experience of fatherhood in foster care or on related outcomes for fathers in care such as residency with children, father engagement with children, coparental relationship quality, or the health and well-being of their children. While there have been over 60 studies and three reviews on expectant and parenting foster youth spanning roughly 30 years, the articles have primarily focused on empirical findings relating to mothers in foster care. Information on fathers in foster care has received little attention and is restricted to empirical studies. This scoping review aims to fill this gap by examining the available information on fathers in foster care. To this end, our scoping review explores empirical findings and knowledge from practice-, legal-, and policy-related literature related to fathers in foster care from peer-reviewed journal articles, reports, dissertations, white papers, and grey literature published between 1989 and 2021. Findings from 94 sources of evidence on expectant and parenting foster youth suggest that mothers in foster care are consistently the focus of the literature. If fathers in foster care are included in the literature, findings or guidance are often provided in the aggregate (e.g., parents in care). However, when aggregated, literature still focuses on mothers in care, or female pronouns are used to describe the larger expectant or parenting foster youth population. Many of the studies excluded fathers, and the primary exclusion rationale includes a lack of identified fathers in care, unreliable child welfare data on fathers, or high attrition of fathers in parenting services. In terms of information on fathers in foster care by the source of evidence, research papers often provided quantitative descriptions of fathers, practice papers focused on rights of fathers, legal papers centered on paternity establishment or paternal rights, and policy papers largely discussed the need for improved data tracking and interventions for fathers. More research is needed to support fathers in foster care as they transition out of care into early adulthood and young fatherhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Youth in foster care have an increased likelihood of becoming parents as compared to their non-foster care peers (Courtney & Dworsky, 2006). Parenting while in foster care is associated with a variety of risk factors for young parents and their children, including adverse outcomes in education (Courtney & Hook, 2017), employment (Dworsky & Gitlow, 2017), housing stability, mental health (Matta Oshima et al., 2013) and criminal justice involvement (Shpiegel & Cascardi, 2015), and intergenerational maltreatment (Dworsky, 2015). As such, young parents in foster care have garnered the attention and concern of scholars, policymakers, and child welfare practitioners, including 30 years of research on this population. Relatively little attention has been paid to the outcomes, experiences, and needs of young fathers in care. The lack of research on fathers in foster care may stem from limitations in survey and child welfare administrative data to accurately capture reports of males impregnating females or fathering a child when paternity is unreported, disputed, or unknown. Further, research indicates that many young fathers in foster care are dually impacted by child welfare and criminal justice involvement (Shpiegel & Cascardi, 2015), which may constrain researchers’ abilities to connect with young fathers in foster care for rigorous qualitative research. Furthermore, research on young fathers (e.g., adolescent, teenage) broadly indicates that young fathers have unique needs related to their delayed entry into the labor force, lower academic achievements, and decreased developmental readiness for paternal obligations, which may affect their ability to meet traditional fatherhood expectations (Johnson Jr., 1998, 2001a, 2001b).

There are three existing literature reviews on expectant and parenting youth in foster care, which collectively review research published between 1989–2017. Each of these reviews covers research that includes a sample of only young mothers or a sample of both young mothers and young fathers together. None of the three reviews covers research that includes a sample of only young fathers. Svoboda et al. (2012) examined literature on parenting youth in foster care published from 1989–2010, identifying common themes across the 16 quantitative and qualitative studies reviewed. The authors note variation across studies in reported rates of pregnancy and impregnation, ranging from 16 to 50% of youth in care who either became pregnant or impregnated someone while they were in foster care. Common themes across the studies include barriers and opportunities, diverse mental and physical health needs of parenting youth, the influence of traumatic life experiences on sexual development, the influence of poverty, and the disruption of relationships and living environments. Although nine of the sixteen studies included fathers in the sample, the authors did not identify any implications for research or policy related to young fathers in foster care. Connolly et al. (2012) conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies published on expectant and parenting youth in foster care in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. They identified risk factors, protective factors, and markers of resilience across 17 studies published between 2000–2010. The authors identified several themes related to what they identify as the experiences of young mothers in foster care, including (1) infants filling an emotional void (2) lack of consistent sexual education, (2) motherhood adversities, (4) mistrust of others and social stigma, (5) perception of motherhood as positive and stabilizing (6) internal strengths and wanting to do better, and (7) support contributing to positive motherhood. Interestingly, the Connolly et al. (2012) review focuses on the findings and implications of the studies solely for young mothers in foster care and their children. However, of the studies reviewed that are based in the United States, the majority included young fathers in foster care in the sample, but father-specific findings were not discussed. In the most recent literature review on this population, Eastman, Palmer, et al. (2019), Eastman, Schelbe, et al. (2019)) reviewed 18 studies on young parents in care published between 2011 amd 2017. Of the studies reviewed, nine included fathers in the sample. Although the authors highlighted some of the findings on expectant and parenting males in care, no father-specific recommendations for child welfare policy, practice, or future research were made.

Across the three reviews, 19 studies included fathers in the sample. However, few studies reviewed identified implications specifically for young fathers and their children, and the existing reviews are similarly disengaged from father-related findings. As such, there are three notable gaps in current understandings of the research on young fathers in foster care. First, current reviews have not thoroughly analyzed the existing body of research published from 1989 and 2017 in terms of father-related findings, including some publications omitted from prior literature reviews. Second, additional research on expectant and parenting youth in foster care has been published from 2018–2021 and has yet to be reviewed for father-related findings. Third, none of the existing literature reviews include research exclusively focused on young expectant and parenting males in foster care. The objective of this scoping review is to address each of these gaps in order to identify the risks, experiences, and needs of young fathers in foster care with implications for child welfare policy, practice, and research. Furthermore, this scoping review seeks to explore in detail the available information on young fathers in foster care spanning the last 30 years. This 30-year span covers the oldest study (Polit et al., 1989) included in the first review of research on expectant and parenting foster youth by Svoboda and colleagues (2012) to the most recent studies reviewed in this scoping review (Dworsky et al., 2021; Martínez-García et al., 2021; Rouse et al., 2021; Shpiegel, Day, et al., 2021; Shpiegel, Fleming, et al., 2021).

Methods

This scoping review began with the establishment of a research team consisting of the two authors of this paper who have practice and research experience with expectant and parenting youth in foster care. We collaborated on identifying the research question for this scoping review, including target audiences, search terms, and databases to conduct the searches. The methodology we used for this scoping review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols extension for scoping reviews framework (Tricco et al., 2018). We completed a detailed review protocol for our scoping review but did not register it. Registering scoping reviews is recommended but not required to reduce duplication of research and for transparency (Tricco et al., 2018). However, we choose not to register our scoping review protocol due to the simplicity of our inclusion criteria (i.e., research containing any findings or information on fathers in foster care). Due to the scarcity of research on fathers in foster care, we were not concerned with the duplication of a research review on this topic. However, if one were to occur, we would welcome the possibility of different conclusions or alternative sources of evidence on this topic. To ensure transparency, our review protocol can be obtained from the primary author upon request and we detail the methods of our scoping review in the next section.

This study is a scoping review of expectant and parenting fathers in foster care. However, we decided to include expectant and parenting mothers in foster care in this scoping review as well. Given that our decision may seem perplexing, we believe that our rationale for including mothers in foster care in this scoping review is warranted. Scoping review methodology is used for variety of purposes (Peterson et al., 2017; Pollock et al., 2021). Two primary purposes of a scoping review are to provide an overview of a field of research (Moher et al., 2015; Pham et al., 2014) and to identify gaps in existing literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Sucharew, 2019). Our scoping review aligns with these purposes in two ways. First, we aimed to provide an overview of the field of research on expectant and parenting foster youth, examining the extent of research done on fathers in foster care. Second, we aimed to identify gaps in existing literature on expectant and parenting foster youth as they relate to fathers in foster care. To achieve these two aims, we review literature on expectant and parenting foster youth broadly (e.g., literature including mothers, fathers, or both) to ascertain the degree to which fathers in foster care are included in research literature (e.g., main sample or comparison group) or white/grey literature (e.g., principal focus or related focus).

Research Question and Purpose

Our scoping review was guided by the research question, “What are the research findings on or guidance for working with expectant and parenting fathers in foster care?” The purpose of our review was to search, identify, and summarize the literature on fathering foster youth that is relevant to research, legal, policy, and practice audiences.

Eligibility Criteria

Documents were eligible for inclusion if they contained one or more of the following elements of information on expectant or parenting fathers in foster care: (1) research findings, (2) legal guidance, (3) policy guidance, or (4) practice guidance. We included documents if they were published between 1989 and 2021, written in English, based in the United States, and either peer-reviewed journal articles, reports, dissertations, white papers, or grey literature. We included documents if they used quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method, or art-based research methodologies. In addition to the eligibility criteria stated above, we included any peer-reviewed publications or report studies that included only pregnant or parenting mothers in foster care and studies in which the gender of the parent in foster care was not clearly stated (e.g., “parents in foster care,” “parenting youth in foster care”). We expanded the eligibility criteria of peer-reviewed publications and reports to include studies on mothers in care and studies that may include fathers in care for comparative purposes (e.g., obtain the proportion studies including fathers in care versus solely mothers in care). For white papers and grey literature, we excluded any documents that made ambiguous or minimal references to fathers in foster care (e.g., “services should include parents in care,” “services should include mothers and fathers in care”).

Information Sources and Search Strategies

To identify potentially relevant documents, we searched the following online bibliographic databases in May and June of 2021: Google Scholar, Google, ArticlesPlus, PubMed, EBSCO, Web of Science, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, and HeinOnline. We used Google Scholar, Scite.ai, ConnectedPapers, and Dimensions.ai to conduct forward and backward citation searches. We searched Google Scholar, ArticlesPlus, PubMed, EBSCO, Web of Science, and HeinOnline for peer-reviewed research studies, reports, and legal publications. We searched ProQuest Dissertations & Theses for dissertation studies and searched Google for white papers, grey literature, and other reports not captured in earlier database searches. We developed and used a combination of the following Boolean search terms for each search to ensure that results were relevant to our research question and search: “adolesc*” OR “teen*” OR “young” OR “youth*” AND “father*” OR “mother*” OR “parent*” OR “expect*” OR “preg*” AND “in care” OR “foster care” OR “child welfare” OR “child protection” OR “child protective.” We searched databases for these Boolean search terms in the title, abstract, full-text, or keywords. The searches were conducted by both authors of this paper.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

Following the search, we conducted a two-phase selection process. In the first phase, we identified possible citations, collected citation data, uploaded citation data (e.g., title, author(s), journal, abstract, and DOI/URLs) into Zotero 5.0, and removed duplicates. In the second phase, we screened citations by assessing the citation data against the eligibility criteria for our review. We retrieved the online full-text of potentially relevant sources, read the text, and assessed the text against the inclusion criteria. We used different selection processes for each source of evidence that matched our eligibility criteria. For peer-reviewed publications and reports, we automatically included a study or report if they were reviewed in previous review studies (i.e., Connolly et al., 2012; Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019; Svoboda et al., 2012). We also included any peer-reviewed publications and reports that met our eligibility criteria and were published but not reviewed in previous review studies (between 1989 and 2017), as well as peer-reviewed publications and report studies published after the 2017 eligibility year cut-off for the Eastman, Palmer, et al. (2019) and Eastman, Schelbe, et al. (2019) review (between 2018 and 2021). When peer-reviewed publications and report studies met our eligibility criteria, we conducted forward and backward citation searches to find additional studies for inclusion based on our eligibility criteria. We selected dissertations, white papers, and grey literature if the publications met our eligibility criteria and had distinct findings or guidance for fathers in foster care. Each author reviewed eligible studies for selection as sources of evidence. We resolved disagreements on publication selection through review and discussion.

Data Charting and Item Extraction

We developed and used a data-charting form to collect, track, and assess data variables to extract. We independently charted the data, discussed the results, and continuously updated the data-charting form in an iterative process based on information contained in the publications that varied based on the type of publication and target audience. We extracted data items from the publications included in our scoping review using a data extraction tool we developed. The data items we extracted from publications included specific details on the topic of the publication (e.g., expectant fathers, fathering, father rights), study sample (e.g., fathers, mothers, both), study context (e.g., research, policy, legal), research findings (e.g., for fathers, mothers, both), and implications (e.g., suggestions for future research, practice guidance).

Synthesis of Results

We grouped the studies by the type of publication and audience. We synthesized peer-reviewed research studies, report studies, and dissertations together for research audiences. We grouped legal studies together for law and advocacy audiences. Lastly, we grouped policy and practice-focused white papers and grey literature together for policy- and practice-related audiences. When we found reviews on pregnant, expectant, and parenting youth in foster care, we noted how many studies may have been missed or excluded from previous reviews and how many studies were published outside of year ranges covered in previous reviews. When we synthesize findings from peer-reviewed studies and report studies that were reviewed in previous review studies (Connolly et al., 2012; Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019; Svoboda et al., 2012), we focus on synthesizing father-specific findings, study procedures, and implications.

Results

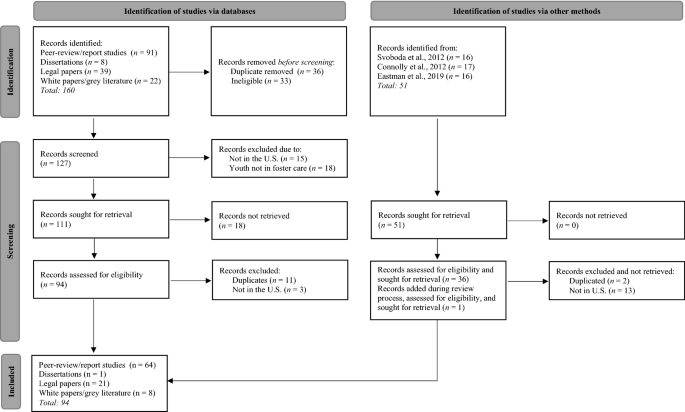

As shown in Fig. 1, after our initial search, we identified 160 sources of evidence. Thirty-six sources of evidence were duplicates of studies we found in our databases searches and studies we included from previous reviews on pregnant, expectant, and parenting youth in foster care (Connolly et al., 2012; Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019; Svoboda et al., 2012) that met our eligibility criteria. Thirty-three sources of evidence were removed that did not meet eligibility criteria. We were then left with 127 sources of evidence that we reduced down to 93 after reviewing sources of evidence that did not meet eligibility criteria (n = 18). During the review process, we added one source of evidence (grey literature) at the suggestion of a reviewer that we missed during the screening process. Of the 94 sources of evidence we included, 64 were peer-review or report studies, 1 was a dissertation, 21 were legal papers, and 8 were either white papers or grey literature. The selected articles highlighted six areas of interest regarding expectant and parenting male youth in foster care: (1) incidents of impregnation by males in foster care; (2) predictors and characteristics associated with fathering while in foster care; (3) risk factors of early fatherhood in care; (4) elements of fathering roles while in foster care; (5) legal rights of fathers in foster care; and (6) practice with fathers in care.

Review of Peer-Reviewed and Report Studies Reviewed in Previous Review Studies

The three previous reviews on expectant and parenting youth in foster care collectively reviewed 37 studies conducted between 1989–2017. Studies across these three reviews, which primarily focus on young expectant and parenting mothers in foster care, include fourteen studies that address pregnancy and birth incidence and various demographic characteristics of expectant and parenting youth in care (Combs et al., 2018; Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2012; Dworsky, 2015; Dworsky & DeCoursey, 2009; Dworsky & Gitlow, 2017; Gotbaum et al., 2005; Krebs & de Castro, 1995; Leslie et al., 2010; Milbrook, 2012; Putnam-Hornstein & King, 2014; Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2016; Shpiegel & Cascardi, 2015; Shpiegel et al., 2017), six papers on sexual risk behaviors (Coleman-Cowger et al., 2011; Constantine et al., 2009; James et al., 2009; Matta Oshima et al., 2013; Polit et al., 1989; Zhan et al., 2019), six papers on child welfare placements and pregnancy (Carpenter et al., 2001; Kerr et al., 2009; King & Van Wert, 2017; Leve et al., 2013; Lieberman et al., 2015; Sakai et al., 2011), three papers on transition aged youth and parenting (Collins et al., 2007; Haight et al., 2009; Max & Paluzzi, 2005), two papers on mental health and substance use (Milbrook, 2012; Matta Oshima et al., 2013), and seven papers on parenting experiences (Aparicio, 2017; Aparicio et al., 2015; Budd et al., 2006; Love et al., 2005; Mena, 2008; Pryce & Samuels, 2010; Radey et al., 2016; Schelbe & Geiger, 2016). We revisited the studies in these reviews and analyzed them based on several factors: (1) inclusion of young fathers in foster care in the sample, (2) findings related to young fathers in foster care, (3) mention of fathers of children with a mother in foster care, and (4) mother-focused studies that either have exclusion criteria for fathers in care or (5) that make recommendations related to fathers in care. As shown in Table 1, 22 of the 37 previously reviewed studies included expectant and parenting fathers in foster care in the sample. Among the remaining 15 studies that did not include expectant or parenting fathers in foster care in the sample, five studies discussed fathers of children with a mother in foster care or made father-related recommendations.

Nine of the fourteen previously reviewed studies on the incidence of pregnancies and births and characteristics of expectant and parenting youth in care included fathers in the sample. Three studies reported incidence of pregnancy or impregnation by gender (Combs et al., 2018; Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2016), while one additional study reported aggregate pregnancy or birth incidence (Leslie et al., 2010). Among the studies that reported incidence of impregnation in the sample, rates of fathering a child while in foster care ranged from 13.8% (Courtney & Dworsky, 2006) to 22% (Combs et al., 2018). The majority of impregnation by males in foster care resulted in a live birth. None of the studies report the age or race of fathers in care specifically. However, Courtney and Dworsky (2006) reported that in the Midwest Study sample, by age 19, 13.8% of males had impregnated a female. In all studies conducted in Illinois that report racial demographics, African American youth are disproportionately more likely to become parents (Dworsky, 2015; Dworsky & DeCoursey, 2009; Dworsky & Gitlow, 2017), as more than 80% of parenting youth in each sample were identified as African American. In the CalYOUTH study, however, young parents were most likely to be of mixed race (Courtney et al., 2016).

Four studies address predictors of fathering a child while in foster care in the domains of placement type (Sakai et al., 2011), substance use treatment history (Coleman-Cowger et al., 2011), and mental health status (Matta Oshima et al., 2013), and other indicators of risk (Matta Oshima et al., 2013). Sakai and colleagues (2011) found that youth placed in kinship care were seven times more likely to become pregnant (females) or impregnate a female (males) than youth placed in traditional foster care. Males in substance use treatment with a foster care history, however, were less likely than their female counterparts to become expectant or parenting (Coleman-Cowger et al., 2011). On the other hand, Matta Oshima et al. (2013) found that males in foster care with a mental health diagnosis were significantly more likely to father a child than those without a diagnosis. Matta Oshima et al. (2013) indicated several predictors of becoming a father while in care in their analysis of longitudinal data from a study of 325 youth in care, including endorsing a substance use disorder, failing grades, and leaving care before age 19. Males who were not yet sexually active by age 17 were less likely to father a child between ages 17 and 19.

In addition to predictors of fathering among males in foster care, several studies illustrate characteristics of the population. Fathers in foster care are unlikely to reside with their children. For example, Courtney and Dworsky (2006) found that only 18.4% of fathers in the Midwest Study resided with a child. Further, fathers in care face adverse outcomes related to incarceration and housing stability. In their analysis of National Youth Transition Database (NYTD) data, Shpiegel and Cascardi (2015) found that 74% of fathers in care had an incarceration history, and one in three experienced homelessness. One study explored rates of employment among both mothers and fathers in foster care, indicating that mothers in care are more likely to be employed for one quarter than fathers in care, with no significant differences in the number of quarters worked or total earnings between genders (Dworsky & Gitlow, 2017). The CalYOUTH study presents the most robust findings on father-specific characteristics among youth in care. In that sample, one-fifth of males had ever gotten a female pregnant, nearly one-tenth had ever fathered a child, and all young fathers reported only having one child. At the time of conception, only 10% of fathers reported using contraception. Further, 20% of fathers reported that they did not want their female partner to become pregnant, while 20% expressed a strong desire for pregnancy (Courtney et al., 2016).

Scholars also consider risk factors associated with fathers in foster care. Although rates of child separation into foster care are higher among children born to young mothers in foster care, one study found that 2.8% of children born to fathers in care entered foster care (Dworsky & DeCoursey, 2009). Another study attributes this, in part, to the fact that most children born to a father in foster care reside with the other parent and maybe under less scrutiny than mothers in care (Dworsky, 2015). In addition to risks associated with child welfare involvement, Courtney et al., 2012 conducted a Latent Class Analysis to understand differences among transition-aged youth, with particular implications for understanding risk factors for young fathers in care. Fathers were most clearly represented in the “Struggling Parents” and “Troubled and Troubling” classes. Struggling parents, of which fathers represent approximately one-quarter of the sample, were more likely to reside with their child, more likely to be married than other classes, and have lower criminal justice involvement than other classes. On the other hand, males make up 75% of the Troubled and Troubling class, of which half are parents and none co-reside with their children. This class also included high rates of criminal justice involvement among males (Courtney et al., 2012). Findings from Courtney and colleagues (2012) demonstrate the unique experiences of fathers in foster care, which may be stressors in the transition to young adulthood and early fatherhood.

Four studies address aspects of fathers’ experiences and roles as fathers while in foster care. Collins et al. (2007) analyzed data from youth who re-entered care after age 18 in Massachusetts, with four parenting youth in the qualitative sample (n = 16). One father identified reuniting with his child as a goal of re-entering care. In their study of both young mothers’ and young fathers’ experiences in foster care, Love and colleagues (2005) suggest services targeting the unique needs of fathers in foster care, including addressing gendered double standards related to parenting that may place more parenting responsibilities on mothers. Schelbe and Geiger (2016) studied mothers and fathers in care as well but presented findings specific to fathers in care. Fathers (n = 12) expressed joy and pride in the fathering role, identifying a wide range of father involvement and engagement with their children. Findings from the CalYOUTH study also include findings on father involvement and engagement. Fathers in the study were more likely (58.7%) to reside with the child’s other parent compared to mothers. Fathers also reported high rates of equal involvement, with 87.7% of fathers reporting that they spent equal time with their children. Fathers also reported regularly routine activities with their children, including eating an evening meal, bathing, and putting their children to bed (Courtney et al., 2016). Fathers also may receive less support from caseworkers and other child welfare staff related to fathering. One study addressed caseworker approaches to serving fathers in foster care. Caseworkers reported that they were less likely to provide family planning guidance to males (23%) compared to females (34%) (Constantine et al., 2009).

In addition to studies that included fathers in the sample, five studies that did not include fathers in care mentioned fathers of children with a mother in care. In two of the studies, authors described relationships between mothers in care and their children’s fathers, indicating when mothers discussed residing with fathers and coparenting (Pryce & Samuels, 2010), as well as cases in which such relationships were both sources of volatility and support (Haight et al., 2009). Three other studies made recommendations for scholars and practitioners to increase knowledge about young fathers in care (Aparicio et al., 2015) and to attend to the importance of healthy coparenting relationships (Lieberman et al., 2015; Max & Paluzzi, 2005).

Review of Peer-Reviewed and Report Studies Not Reviewed in Previous Review Studies

Building on the father-related findings in studies covered in the three existing literature reviews on expectant and parenting youth in foster care, we conducted a new analysis of 28 studies not included in prior reviews. Six of the studies were published between 2007 and 2016 but were not included in the most recent review (Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019). The additional 22 studies on expectant and parenting youth in foster care were published between 2017 and 2021. Of the 28 studies added to this review, only 8 included fathers in care in the sample. Like in the studies covered in prior reviews, this group of studies present findings related to fathers in care in several domains: (1) incidents of impregnation by males in foster care; (2) predictors and characteristics associated with fathering while in foster care; (3) risk factors; (4) elements of fathering roles while in foster care. Further, a new domain emerged in this group: (5) service provision.

Half of the studies including fathers in care in the sample addressed reported rates of impregnation (Combs et al., 2018; Gordon et al., 2011) and characteristics of fathers (Combs et al., 2018; Gordon et al., 2011; Melby et al., 2018; Rouse et al., 2021). Rates of impregnating a female were 27.5% (33% by age 21; Combs et al., 2018) to 49% (Courtney et al., 2007). In a study by Rouse and colleagues (2021), males reported having more sexual partners but were less likely to discuss sexual risk with child welfare staff than their female counterparts. When pregnancy occurred, 82.7 of expectant mothers reported including the father of their baby in decision making about whether or not to continue the pregnancy and parent. Further, they describe additional characteristics among fathers in care (n = 11), including rates of unmarried cohabitation (72.7%), established paternity (33.3%), and several domains related to child support. Similarly, Gordon et al. (2011) presented a broad set of characteristics in their analysis of survey data on 32 fathers in foster care. They found that 50% of fathers had determined paternity status, 72% were enrolled in school, 50% reported involvement with their child, 44% had regular contact with their children, and 16% of children were child welfare involved. In the study by Combs et al. (2018), the mean age for males getting a female pregnant was 18, which was slightly higher than the mean age for females. Among males who impregnated a female, 63% resulted in a live birth, 13% ended in abortion, 11% were expectant at the time of interview, 87% of males were currently employed vs. 37% of females. Similar to earlier studies, new research indicates that sexual risk behaviors are associated with higher rates of impregnation among males, although males in foster care have lower rates of getting a female pregnant than rates at which females in care become pregnant (Zhan et al., 2019).

One study addresses how child welfare involvement influences fatherhood experiences. Manlove et al. (2011) found that limited placement options for fathers in foster care constrained involvement with their children. Further, child protective services (CPS) involvement created difficulties for fathers of children with mothers in foster care to be involved with or live with their children. The authors recommend that child welfare systems provide appropriate placements and services to promote responsible fatherhood. Further, Martínez-García et al. (2021) conducted a photovoice project with parenting foster care alumni regarding parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fathers were represented in the domains of coparenting, reuniting with children, and the joys and challenges of fathering in the pandemic.

This more recent set of studies addresses service provision for parenting youth in care with more depth than previous research. Four studies address services for expectant and parenting youth in care. In their analysis of data from CPS workers, Leigh et al. (2007) found that services are less likely to be provided to young fathers in care than to mothers in the domains of prenatal care and counseling, parenting skill-building, and childcare. Services provided to fathers include parenting skills classes/fatherhood training, counseling, and job/skill training or vocational training. Further, another study of caregiver perspectives on parenting male and female youth in care around issues of sexuality demonstrated challenges in addressing sexual risk behaviors, identifying barriers to communication, and effective monitoring of sexuality with youth in foster care (Albertson et al., 2018). Finally, two publications on a pilot implementation study with young mothers in foster care presented implications for father engagement in services. Findings indicated that home visitors engaged fathers with children of young mothers in care in home visiting sessions, distributed father-specific materials, and provided support around co-parenting and relationship conflicts to approximately a quarter of families (Dworsky et al., 2021). More specifically, home visitors conducted 88 visits with 18 young mothers that addressed father involvement. Home visitors discussed working with clients around father incarceration and improving coparenting. The authors point out the importance that future work on home visiting services with expectant or parenting youth in care include fathers in care.

Several new studies on expectant and parenting youth in care omitted fathers from the sample. Of those studies, six discussed fathers of children with mothers in care or provided exclusion rationale. Half of these studies illustrated challenging aspects of relationships between young mothers in care and their children’s fathers (Bermea et al., 2019), including the complexities due to technology (Bermea et al., 2019) and reports of physical abuse towards children (Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019; Eastman, Schelbe, et al., 2019). In their analysis of CPS case records for children with mothers in care, Eastman, Palmer, et al. (2019), Eastman, Schelbe, et al. (2019)) found that few fathers were involved and supportive and that, in some cases, fathers were indicated as physically abusive towards the children. In another study of CPS involvement of children of mothers in foster care, Eastman and Putnam-Hornstein (2019) indicated that established paternity was used as a covariate in their analysis, but that fathers were excluded because paternity is difficult to identify using birth records. However, they identify that paternity establishment for fathers of children with a mother in care is a strong protective factor against generation CPS involvement and that future research should focus on the establishment of paternity among fathers in care and the effect it has on generation CPS involvement. In addition, Shpiegel and Cascardi (2018) studied young mothers in care but indicated a general need for research on fathers in foster care.

Review of Dissertations

We only identified one dissertation (Murray, 2016) that focused on fathers in foster care. However, the ages of the fathers ranged from 25 to 54 years of age–well past the age when fathers could have been in foster care. Since this was a qualitative study of the experiences of fathers with foster care histories, and the children they are reporting on could have been born while the fathers were in foster care, we decided to include it in our review. In her qualitative dissertation study of 10 fathers with foster care histories, Murray (2016) found that most fathers in her study were committed to their role as a father and were, or at least spent significant time being, involved in the lives of their children. However, some fathers experienced challenges with coparenting, substance use, single fatherhood, and child welfare involvement (of their children). While the findings around challenges to fatherhood in this dissertation study may not have direct connections to the foster care system, they are certainly reflective of similar findings on fathers in foster care shared in this review.

Review of Legal Papers

As displayed in Table 2, we identified 21 papers covering a range of legal topics relating to expectant and parenting foster youth, including five papers on legal reproductive rights (Dudley, 2013; Manian, 2016; Moore, 2012; Pedagno, 2011; Wallis, 2014), ten papers on parental rights (Baynes-Dunning & Worthington, 2012; Benjamin et al., 2006; Garlinghouse, 2012; Harkness et al., 2017; C. C. Katz & Geiger, 2021; S. Katz, 2006; Pokempner, 2019, 2020; Riehl & Shuman, 2019; Stotland & Godsoe, 2006), and six papers on legal representation in child welfare courts (Barry, 2017; Bonagura, 2008; Buske, 2006; Fines, 2011; Hirst & Jones, 2016; Horwitz et al., 2011). Among these legal papers on expectant or parenting foster youth, no papers focused solely on fathers in care, three papers made mention of expectant or parenting fathers in care (Benjamin et al., 2006; S. Katz, 2006; Pokempner, 2020), ten papers discussed expectant or parenting fathers and mothers in care together (Barry, 2017; Bonagura, 2008; Buske, 2006; Dudley, 2013; Harkness et al., 2017; Hirst & Jones, 2016; Horwitz et al., 2011; Pokempner, 2019; Riehl & Shuman, 2019; Stotland & Godsoe, 2006), seven papers focused solely on pregnant females or mothers in foster care (Baynes-Dunning & Worthington, 2012; Fines, 2011; Garlinghouse, 2012; Manian, 2016; Moore, 2012; Pedagno, 2011), and the parental context of one paper was difficult to ascertain (C. C. Katz & Geiger, 2021).

Among the three legal papers that mentioned fathers in foster care, two papers supplied legal guidance for fathers in care but did so in the context of mothers in care. Katz (2006) and Pokempner (2020) both state that fathers in foster care have the same rights as mothers in foster care, including placement with their child, access to parental services, and child-parent visitation for nonresident parents. Only one paper focused on legal guidance that was unique to fathers in foster care. Benjamin et al. (2006) discussed the importance of fathers in foster care to establish paternity for their children and the associated paternal rights of fathers in care who have established paternity, including their legal right to father-child visitation, child custody, and legal representation when their paternal rights are violated.

For the ten papers that discussed legal guidance for fathers and mothers in foster care together, most of the discussions were on the legal rights of parents in foster care generally but centered on mothers in care or used female gender pronouns when discussing parenting foster youth in the aggregate. None of these ten papers shared legal guidance specifically targeting fathers. For example, four of the ten papers (Barry, 2017; Bonagura, 2008; Hirst & Jones, 2016; Stotland & Godsoe, 2006) provide legal insight around parental rights while in foster care for parents in care generally, but only mothers in care are discussed when providing legal details or case examples. When references to fathers are made within these papers, the references are in the context of the father of a child with a mother in foster care, not specifically fathers in foster care. In six of the ten legal papers referencing “parents” in foster care generally, two papers (Buske, 2006; Harkness et al., 2017) only used female gender pronouns, and four papers (Dudley, 2013; Horwitz et al., 2011; Pokempner, 2019; Riehl & Shuman, 2019) used no pronouns at all. In another six papers that did not include discussions of fathers, nearly all discussions addressed legal issues commonly associated with female youth, such as pregnancy rights, pregnancy prevention, and reproductive rights. However, among the ten papers that included fathers in foster care but instead focused on mothers in foster care, the rationale for the focus on mothers in care included statements that “father’s involvement is often minimal” (Manian, 2016, p. 157), “majority of parenting wards who seek to live with their children are female,” and “for convenience” (Stotland & Godsoe, 2006, p. 2).

Review of Policy and Practice Literature

During our search for policy and practice literature discussing expectant and parenting foster youth, we found many reports, guides, and toolkits that only made passing references to fathers. While reviewing the literature for inclusion into this review, we decided to select exemplar resources that illuminated aspects of fatherhood in foster care not often discussed in research papers on expectant and parenting fathers in foster care. As displayed in Table 3, resources that we selected for inclusion provide policy- and practice-related supports and guidance pertaining to fathers in care on topics such as data collection, policy directives, client rights, and future research. For example, a publication from Annie E. Casey Foundation (2019) recommends that data on expectant and parenting fathers in foster care may be improved by using methods to better track expecting fathers in foster care and record efforts to engage and support fathers in care. Publications from Children’s Defense Fund (2020) and Center for the Study of Social Policy (2019) detail how evidence-informed and promising practices can be leveraged to better support fathers in foster care through The Family First Prevention Services Act and Title IV-E prevention efforts. Furthermore, literature such as the reports by the Center for the Study of Social Policy (Harper Browne, 2015; Primus, 2017) uses existing fatherhood research to demonstrate how fathers in foster care can positively impact their children’s lives, be better served by father-focused foster care services, and effectively exercise their paternal rights in the child welfare system.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review has several strengths. One strength is that this is the first review to articulate the current state of literature on expectant and parenting foster youth as it relates to fathers in foster care. Our findings on the lack of available information on fathers in foster care demonstrate the need for further inquiry by researchers, legal representatives, policy makers, and practitioners on the outcomes, needs, and experiences of fathers in foster care. Another strength is that this review articulates gaps in practice-, legal-, and policy-related literature that should be further developed to improve our knowledge on fathers in foster care. Addressing these gaps in the literature will likely lead to improved research, better services, stronger legal representation, and more effective policies for fathers in foster care.

However, findings in this scoping review are subject to at least eight limitations. First, our scoping review may have missed some literature due to our search strategies and databases we used. Although we carefully chose key search terms and databases to conduct searches for this scoping review, eligible literature related to fathers in foster care could have been missed at screening. For example, we may have missed eligible literature that did not include our specific search terms, was not electronically searchable, or was not archived electronically in the databases we used. Second, our scoping review does not include literature published prior to 1989, written in a language other than English, and not based in the United States. While we chose search criteria that was most relevant to recent research conducted in the United States, this scoping review may lack historical, cultural, or geographical context that is relevant to understanding fathers in foster care. Third, our scoping review includes emerging themes and findings that were derived from only two researchers. While consensus was researched among key themes and findings by researchers with practice and research expertise with expectant and parenting foster youth, other researchers may find alternative themes or competing findings. Fourth, our scoping review lacks critical appraisal of included literature. While we comprehensively share themes from literature on fathers in foster care, we do not individually assess the quality of research evidence in peer-reviewed journal articles nor do we ascertain the validity of information contained in reports, dissertations, white papers, or grey literature. Fifth, terminology used across sources of evidence varied in conceptualization. For example, some studies use the term “fathered” or “paternity” to represent a male getting a female pregnant, a male who got a female pregnant resulting in a birth of a child, or both. Additionally, some sources used terms synonymously that have quite different meanings. For example, some sources used “expectant” with fathers to denote a male who impregnated a female but did not share findings related to this specific stage of fatherhood (e.g., fathers awaiting the birth of a child). We have tried to consistently interpret findings using consistent language (e.g., impregnation, expectancy, fathering, and paternity) but we may have misinterpreted findings where authors used ambiguous father-related terms. Sixth, ages of young fathers in foster care vary in the studies we reviewed. Studies included in our review focused roughly on ages 18–21 years, but some samples included fathers younger than 18 years old (i.e., not in extended foster care), between 18 years old and 21 years old (i.e., possibly in extended foster care), older than 21 years old (i.e., beyond the age of extended foster care) or all three. We were unable to assess the extended to which fathers' age (e.g., adolescent, early adult, or emerging adult), foster care status (e.g., in care, left care, or left care and returned to care), or extended foster care status (e.g., in extended foster care or not in extended foster care) affected the lived experience in young fathers in care. This limits our ability to understand how fathers' developmental status or foster care characteristics affects fatherhood in foster care. Furthermore, our findings, implications, and recommendations are based on findings that include fathers who are more likely to be in care, engaged with caseworkers, or open to sharing their experiences of being a father in foster care. Seventh, the race and ethnicity of young fathers in foster care vary in the studies we reviewed. While we share key findings by race and ethnicity when reported, there was a lack of findings or information focused on racial and ethnic minority fathers in care. The findings we share do not adequately shed light on the experience of fatherhood for racial and ethnic minority fathers in foster care. Eighth, our review does not include father-specific findings for single fathers, sexual minority fathers (SMF), gender minority fathers (GMF), or all three. The overwhelming parental structure in the studies we reviewed were father-mother (e.g., father in foster care did not give birth, mother gave birth). We did not identify any study that investigated single father parental structures (e.g., father, SMF, or GMF in foster care gave birth, adopted, or assumed guardianship; no coparenting father or mother) or father-father parental structures (e.g., father, SMF, or GMF in foster care gave birth, adopted, or assumed guardianship; other father did not give birth, adopt, or assume guardianship). Therefore, findings we review and recommendations we make are limited to father-mother parental structures.These limitations potentially undermine the validity of our themes, affect the generalizability of our findings, and may bias the recommendations we make for research-, practice-, legal-, and policy-related audiences.

Discussion

The existing research on expectant and parenting fathers in foster care spans 30 years yet remains sparse both conceptually and methodologically. Research reporting the incidence of paternity among young fathers in care presents a broad range of rates, indicating challenges with accurate reporting of data. The current literature reports rates of impregnation ranging from 27.5 to 49%, with many rate estimates in between. Prevalence rates for expectant fathers in foster care are limited since current efforts to track and monitor fathers in care are limited to caseworkers and fathers’ self-reports, which are likely under counted. Furthermore, there are currently no mechanisms enforcing child welfare agencies to track and report father involvement in the lives of their children. This makes it difficult to determine the kinds of father-focused services to provide to young fathers in foster care. For much of the research on fathers in care, findings are provided in the aggregate, making it difficult to determine findings that are unique to fathers.

The lack of focused research on fathers in foster care is problematic since it gives little insight on how to best support and prepare a population of young fathers who are simultaneously preparing to leave the foster care system, preparing for adulthood, and entering young fatherhood. For example, there is a general lack of empirical research on outcomes of fathers in foster care during the transition to adulthood that may affect their ability to parent their children, such as educational attainment, employment rates, wages, housing stability, victimization, risky behaviors, or mental health issues. Furthermore, There is also relative lack of studies investigating outcomes of or differences between subgroups of fathers in foster care, such as residency with child, age of child, living arrangement with partner, racial/ethnic identity, or sexual minority status. Furthermore, few studies explore fatherhood in the context of direct or indirect father-child interaction theorized as components (e.g., engagement, accessibility, responsibility; Lamb, 2000) or tasks (e.g., positive engagement, warmth/responsiveness, control, indirect care, process responsibility; Pleck, 2010).

Despite the lack of research and knowledge about young fathers in care, research exists on child welfare involved fathers with children in the foster care system that may shed light onto fathers in foster care. For example, the child welfare system has historically ignored, undervalued, and failed to fully engage fathers as agents of change (Jaffe, 1983). Fathers who do engage with the child welfare system often face racial and ethnic experiences of racism and discrimination, particularly among Black fathers (Icard et al., 2017). For example, studies have attributed low father engagement among Black fathers to racialized perceptions and bias among White child welfare caseworkers, attorneys, and judges (Arroyo et al., 2019; Harris & Hackett, 2008). Studies also show that child welfare caseworkers’ can hold negative views of fatherhood roles, such as fathers not being beneficial to child welfare outcomes, not being as needed as mothers, and being harmful to families (Baum, 2017; Bellamy, 2009; Brewsaugh et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2009; Coakley, 2013; Dominelli et al., 2011; Lundahl et al., 2020; Scourfield, 2001).

Given that the child welfare system that struggles to track, engage, and meet the needs of fathers with children in the foster care system as well as young fathers in foster care, more rigorous research is needed to ensure fathers in care are fully supported as they transition out of care into young adulthood and early fatherhood. In alignment with the prevention goals of the Family First Prevention Services Act and Title IV-E, efforts to improve services targeting fathers in foster care may help break the cycle of intergenerational maltreatment of and foster care involvement. To this end, we would like to make the following recommendations considering the findings contained in our review. First, future research should examine ways to better track expectant fathers in care and collect information on diverse forms of father involvement for parenting fathers in care. The improved data on fathers in foster care may likely provide the insight needed to tailor services aiming to strengthen paternal bonds, increase father involvement, and further develop coparenting skills. Second, legal advocates and researchers should examine how the child welfare system affects the paternal rights of fathers in care. An understanding is needed of how the establishment of paternity can be both helpful and harmful to fathers in care, especially when a father encounters a rigid and punitive child support system. For example, the establishment of paternity among fathers in care can strengthen the rights of fathers in care but potentially weaken their ability to meet their paternal obligations or employment and education requirements of extended foster care. Third, policymakers and practitioners should explore how existing fatherhood policies, practices, and interventions may be leveraged in foster care settings to improve the child and family outcomes of fathers in foster care. Such efforts may be effective in interrupting the cycle of intergenerational maltreatment among fathers in foster care and break the cycle of foster care involvement for children born to fathers in foster care.

References

Albertson, K., Crouch, J. M., Udell, W., Schimmel-Bristow, A., Serrano, J., & Ahrens, K. R. (2018). Caregiver perceived barriers to preventing unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections among youth in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 94, 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.09.034

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2019). Expectant and parenting youth in foster care: Systems leaders data tool kit (pp. 1–42). https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-expectantandparentingyouth-2019.pdf

Aparicio, E. M. (2017). ‘I want to be better than you’: Lived experiences of intergenerational child maltreatment prevention among teenage mothers in and beyond foster care: Teen mothers in foster care. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12274

Aparicio, E. M., Pecukonis, E. V., & O’Neale, S. (2015). “The love that I was missing”: Exploring the lived experience of motherhood among teen mothers in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 51, 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.02.002

Aparicio, E. M., Shpiegel, S., Grinnell-Davis, C., & King, B. (2019). “My body is strong and amazing”: Embodied experiences of pregnancy and birth among young women in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.007

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arroyo, J., Zsembik, B., & Peek, C. W. (2019). Ain’t nobody got time for dad? Racial-ethnic disproportionalities in child welfare casework practice with nonresident fathers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 93, 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.014

Barry, E. (2017). Babies having babies: Advocating for a different standard for minor parents in abuse and neglect cases notes. Cardozo Law Review, 39(6), 2329–2366.

Baum, N. (2017). Gender-sensitive intervention to improve work with fathers in child welfare services. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12259

Baynes-Dunning, K., & Worthington, K. (2012). Responding to the needs of adolescent girls in foster care. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law and Policy, 20(2), 321–350.

Bellamy, J. L. (2009). A national study of male involvement among families in contact with the child welfare system. Child Maltreatment, 14(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559508326288

Benjamin, E. R., Keating, A., Lieberman, D., Lipman, J., Schissel, A., Spiro, M., & Stubbs, C. (2006). The rights of pregnant and parenting teens: A guide to the law in New York State (pp. 1–99). New York Civil Liberties Union Reproductive Rights Project. https://www.nyclu.org/sites/default/files/publications/nyclu_pub_rights_parenting_teens.pdf

Bermea, A. M., Forenza, B., Rueda, H. A., & Toews, M. L. (2019). Resiliency and adolescent motherhood in the context of residential foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36(5), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0574-0

Bonagura, R. (2008). Redefining the baseline: Reasonable efforts, family preservation, and parenting foster children in New York. Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, 18(1), 176–233. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/coljgl18&i=177

Brewsaugh, K., Masyn, K. E., & Salloum, A. (2018). Child welfare workers’ sexism and beliefs about father involvement. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.029

Brown, L., Callahan, M., Strega, S., Walmsley, C., & Dominelli, L. (2009). Manufacturing ghost fathers: The paradox of father presence and absence in child welfare. Child & Family Social Work, 14(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00578.x

Budd, K. S., Holdsworth, M. J. A., & HoganBruen, K. D. (2006). Antecedents and concomitants of parenting stress in adolescent mothers in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(5), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.006

Buske, S. (2006). The Adoption and Safe Families Act and teen-parent wards: A misguided game of wait & (and) see parenting, permanency, and the law. Children’s Legal Rights Journal, 26(4), 71–87.

Carpenter, S. C., Clyman, R. B., Davidson, A. J., & Steiner, J. F. (2001). The association of foster care or kinship care with adolescent sexual behavior and first pregnancy. Pediatrics, 108(3), e46–e46. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.3.e46

Center for the Study of Social Policy. (2019). Connecting the dots: A resource guide for meeting the needs of expectant and parenting youth, their children, and their families (pp. 1–103). https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/CSSP-EPY-Resource-Guide-FINAL.pdf

Children’s Defense Fund. (2020). Implementing the Family First Prevention Services Act: A technical guide for agencies, policymakers and other stakeholders (pp. 1–225). https://www.childrensdefense.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FFPSA-Guide.pdf

Coakley, T. M. (2013). An appraisal of fathers’ perspectives on fatherhood and barriers to their child welfare involvement. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23(5), 627–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.775935

Cohen, M., Brown, L. C., Weber, M., Stevens, B., Murphy, S., Ange, M. E., Fenton, D., & Skidmore, M. (2011). A medical guide for youth in foster care (pp. 1–28). New York State Office of Children & Family Services. http://www.ocfs.state.ny.us/MAIN/PUBLICATIONS/PUB5116SINGLE.PDF

Coleman-Cowger, V. H., Green, B. A., & Clark, T. T. (2011). The impact of mental health issues, substance use, and exposure to victimization on pregnancy rates among a sample of youth with past-year foster care placement. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2207–2212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.07.007

Collins, M. E., Clay, C., & Ward, R. (2007). Leaving care in Massachusetts: Policy and supports to facilitate the transition to adulthood (pp. 1–109). Boston University School of Social Work. https://www.bu.edu/ssw/files/pdf/20080603-ytfinalreport1.pdf

Combs, K. M., Begun, S., Rinehart, D. J., & Taussig, H. (2018). Pregnancy and childbearing among young adults who experienced foster care. Child Maltreatment, 23(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517733816

Connolly, J., Heifetz, M., & Bohr, Y. (2012). Pregnancy and motherhood among adolescent girls in child protective services: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 6(5), 614–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2012.723970

Constantine, W. L., Jerman, P., & Constantine, N. A. (2009). Sex education and reproductive health needs of foster and transitioning youth in three california counties (pp. 1–46). Public Health Institute. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.524.5664&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Courtney, M. E., & Dworsky, A. (2006). Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child and Family Social Work, 11(3), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00433.x

Courtney, M. E., Dworsky, A. L., Cusick, G. R., Havlicek, J., Perez, A., & Keller, T. E. (2007). Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at age 21. Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago. https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/Midwest-Eval-Outcomes-at-Age-21.pdf

Courtney, M. E., & Hook, J. L. (2017). The potential educational benefits of extending foster care to young adults: Findings from a natural experiment. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.030

Courtney, M. E., Hook, J. L., & Lee, J. S. (2012). Distinct subgroups of former foster youth during young adulthood: Implications for policy and practice. Child Care in Practice, 18(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2012.718196

Courtney, M. E., Okpych, N. J., Charles, P., Mikell, D., Stevenson, B., Park, K., Kindle, B., Harty, J., Feng, H., & Courtney, M. E. (2016). Findings from the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study (CalYOUTH): Conditions of youth at age 19 (pp. 19–3125). Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Day, A., & Yazigi, L. (2016). Maximizing the education well-being of pregnant and parenting foster youth (No. 7). Wayne State University Policy and Practice Brief. https://depts.washington.edu/fostered/sites/default/files/foster/policy/issue_7-Pregnant-and-Parenting.pdf

Dominelli, L., Strega, S., Walmsley, C., Callahan, M., & Brown, L. (2011). ‘Here’s my story’: Fathers of ‘looked after’ children recount their experiences in the Canadian child welfare system. The British Journal of Social Work, 41(2), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq099

Dudley, T. I. (2013). Foster care, pregnancy prevention, and the law. Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law & Justice, 28(1), 77–115. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/berkwolj28&i=91

Dworsky, A., & DeCoursey, J. (2009). Pregnant and parenting foster youth: Their needs, their experiences (pp. 1–51). Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/Pregnant_Foster_Youth_final_081109.pdf

Dworsky, A. (2015). Child welfare services involvement among the children of young parents in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 45, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.005

Dworsky, A., Gitlow, E., & Ethier, K. (2019). Evaluation of the home visiting pilot for pregnant and parenting youth in care: FY2018 preliminary report. 43. University of Chicago

Dworsky, A., Ahrens, K., & Courtney, M. (2013). Health insurance coverage and use of family planning services among current and former foster youth: Implications of the health care reform law. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 38(2), 421–439.

Dworsky, A., & Gitlow, E. (2017). Employment outcomes of young parents who age out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.032

Dworsky, A., Gitlow, E. R., & Ethier, K. (2021). Bridging the divide between child welfare and home visiting systems to address the needs of pregnant and parenting youth in care. Social Service Review, 95(1), 110–164. https://doi.org/10.1086/713875

Eastman, A. L., Palmer, L., & Ahn, E. (2019). Pregnant and parenting youth in care and their children: A literature review. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36(6), 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00598-8

Eastman, A. L., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2019). An examination of child protective service involvement among children born to mothers in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.002

Eastman, A. L., Schelbe, L., & McCroskey, J. (2019). A content analysis of case records: Two-generations of child protective services involvement. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.030

Fines, B. G. (2011). Challenges of representing adolescent parents in child welfare proceedings. University of Dayton Law Review, 36(3), 307–336. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/udlr36&i=310

Font, S. A., Cancian, M., & Berger, L. M. (2019). Prevalence and risk factors for early motherhood among low-income, maltreated, and foster youth. Demography, 56(1), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0744-x

Garlinghouse, T. G. (2012). Fostering motherhood: Remedying violations of minor parents’ right to family integrity. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law, 15(4), 1221–1258. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/upjcl15&i=1241

Gordon, D. M., Watkins, N. D., Walling, S. M., Wilhelm, S., & Rayford, B. S. (2011). Adolescent fathers involved with child protection: Social workers speak. Child Welfare, 90(5), 95–114.

Gotbaum, B., Sheppard, J. E., & Woltman, M. A. (2005). Children raising children: City fails to adequately assist pregnant and parenting youth in foster care (pp. 1–10). The Public Advocate for the City of New York. https://www.nyc.gov/html/records/pdf/govpub/2708children_raising_children.pdf

Haight, W., Finet, D., Bamba, S., & Helton, J. (2009). The beliefs of resilient African-American adolescent mothers transitioning from foster care to independent living: A case-based analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.05.009

Harkness, R., Abrams, S., & Eskin, A. (2017). Building a safety net for teen parents in foster care: California’s approach parent & child advocacy. Child Law Practice, 36(3), 69–70.

Harper Browne, C. (2015). Expectant and parenting youth in foster care: Addressing their developmental needs to promote healthy parent and child outcomes (pp. 1–46). Center for the Study of Social Policy. https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/EPY-developmental-needs-paper-web-2.pdf

Harris, M. S., & Hackett, W. (2008). Decision points in child welfare: An action research model to address disproportionality. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.09.006

Herrman, J. W., Finigan-Carr, N., & Haigh, K. M. (2017). Intimate partner violence and pregnant and parenting adolescents in out-of-home care: Reflections on a data set and implications for intervention. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(15–16), 2409–2416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13420

Hirst, E. M., & Jones, A. L. (2016). Breaking the cycle of intergenerational child maltreatment: A case for active efforts for dependent minor parents and their children in state custody. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 67(3), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12061

Holtrop, K., Canto, A. I., Schelbe, L., McWey, L. M., Radey, M., & Montgomery, J. E. (2018). Adapting a parenting intervention for parents aging out of the child welfare system: A systematic approach to expand the reach of an evidence-based intervention. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(3), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000308

Horwitz, R., Junge, C., & Rosin, S. (2011). Protection v. presentment: When youths in foster care become respondents in child welfare proceedings. Clearinghouse Review, 45(5), 421–430.

Icard, L. D., Fagan, J., Lee, Y., & Rutledge, S. E. (2017). Father’s involvement in the lives of children in foster care. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12196

Jaffe, E. D. (1983). Fathers and child welfare services: The forgotten client. In M. E. Lamb & A. Sagi (Eds.), Fatherhood and family policy (pp. 129–137). Routledge.

James, S., Montgomery, S. B., Leslie, L. K., & Zhang, J. (2009). Sexual risk behaviors among youth in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(9), 990–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.04.014

Johnson, W. E., Jr. (1998). Paternal involvement in fragile, African American families: Implications for clinical social work practice. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 68(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377319809517525

Johnson, W. E., Jr. (2001a). Young unwed African American fathers: Indicators of their paternal involvement. In A. M. Neal-Barnett, J. M. Contreras, & K. A. Kerns (Eds.), Forging links: African American children clinical developmental perspectives (pp. 147–174). Praeger.

Johnson, W. E., Jr. (2001b). Paternal involvement among unwed fathers. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(6), 513–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00146-3

Katz, S. (2006). When the child is a parent: Effective advocacy for teen parents in the child welfare system. Temple Law Review, 79(2), 535–556. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/temple79&i=543

Katz, C. C., & Geiger, J. M. (2021). The role of court appointed special advocates (CASAs) in the lives of transition-age youth with foster care experience. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00759-8

Kerr, D. C. R., Leve, L. D., & Chamberlain, P. (2009). Pregnancy rates among juvenile justice girls in two randomized controlled trials of multidimensional treatment foster care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 588–593. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015289

King, B., & Van Wert, M. (2017). Predictors of early childbirth among female adolescents in foster care. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(2), 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.014

Krebs, B., & de Castro, N. (1995). Caring for our children: Improving the foster care system for teen mothers and their children. Youth Advocacy Center. https://web.archive.org/web/20041209160843/http://www.youthadvocacycenter.org/pdf/CaringforOurChildren.pdf

Lamb, M. E. (2000) The history of research on father involvement. Marriage & Family Review, 29(2–3), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v29n02_03

Langford, B. H., & Greenblatt, S. B. (2012). Investing in supports for pregnant and parenting adolescents and young adults in or transitioning from foster care (pp. 1–7). Youth Transition Funders Group, Foster Care Work Group. http://www.ytfg.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/FCWG_Pregnant_and_Parenting.pdf

Leigh, W. A., Huff, D., Jones, E. F., & Marshall, A. (2007). Aging out of the foster care system to adulthood: Findings, challenges, and recommendations (pp. 1–126). Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Health Policy Institute. https://teamwv.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/AgingOutOfTheFosterCareSystem.pdf

Leslie, L. K., James, S., Monn, A., Kauten, M. C., Zhang, J., & Aarons, G. (2010). Health-risk behaviors in young adolescents in the child welfare system. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.032

Leve, L. D., Kerr, D. C. R., & Harold, G. T. (2013). Young adult outcomes associated with teen pregnancy among high-risk girls in a randomized controlled trial of multidimensional treatment foster care. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 22(5), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2013.788886

Lieberman, L. D., Bryant, L. L., & Boyce, K. (2015). Family preservation and healthy outcomes for pregnant and parenting teens in foster care: The Inwood House theory of change. Journal of Family Social Work, 18(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2015.974014

Love, L. T., McIntosh, J., Rosst, M., & Tertzakian, K. (2005). Fostering hope: Preventing teen pregnancy among youth in foster care (pp. 1–32). National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy.

Lundahl, B., McDonald, C., & Vanderloo, M. (2020). Service users’ perspectives of child welfare services: A systematic review using the practice model as a guide. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 14(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2018.1548406

Manian, M. (2016). Minors, parents, and minor parents. Missouri Law Review, 81(19), 1–79. http://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol81/iss1/19

Manlove, J., Welti, K., McCoy-Roth, M., Berger, A., & Malm, K. (2011). Teen parents in foster care: Risk factors and outcomes for teens and their children (No. 28; pp. 1–9). Child Trends Research Brief. https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Child_Trends-2011_11_01_RB_TeenParentsFC.pdf

Martínez-García, G., Sanchez, A., Shpiegel, S., Ventola, M., Channell Doig, A., Jasczyński, M., Smith, R., & Aparicio, E. M. (2021). Storms and blossoms: Foster care system alumni parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital Repository at the University of Maryland. https://doi.org/10.13016/OHOX-FBUQ

Matta Oshima, K. M., Narendorf, S. C., & McMillen, J. C. (2013). Pregnancy risk among older youth transitioning out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(10), 1760–1765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.08.001

Max, J., & Paluzzi, P. (2005). Promoting successful transition from foster/group home settings to independent living among pregnant and parenting teens. (pp. 1–8). Healthy Teen Network. https://www.healthyteennetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/PromotingSuccessfulTransitionfromFosterGroupHomeSettingsIndependentLivingPregnantParentingTeens.pdf

Melby, J., Rouse, H., Jordan, T., & Weems, C. (2018). Pregnancy and parenting among Iowa youth transitioning from foster care: Survey and focus group results (Child Welfare Research and Training Project, pp. 1–56). Iowa State University. https://ypii.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ISU-Analysis_Final-Report_09-07-18-1.pdf

Mena, W. F. (2008). Experiences and perceptions of emancipated youth who were pregnant while in the foster care system [Doctoral dissertation]. California State University Long Beach (UMI No. 1455554).

Milbrook, N. (2012). Factors contributing to subsequent pregnancies among teen parents in child welfare [Psy.D., Adler School of Professional Psychology]. http://www.proquest.com/docview/1197258111/abstract/FB5982784F234AB7PQ/1

Moher, D., Stewart, L., & Shekelle, P. (2015). All in the Family: Systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0163-7

Moore, K. (2012). Pregnant in foster care: Prenatal care, abortion, and the consequences for foster families. Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, 23(1), 29–64.

Murray, F. L. (2016). Bringing fathers into F.O.C.U.S.: The lived experiences of fathers who completed a community based fatherhood program (Order No. 10250917) [Dissertation, Texas Woman’s University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Narendorf, S. C., Munson, M. R., & Levingston, F. (2013). Managing moods and parenting: Perspectives of former system youth who struggle with emotional challenges. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(12), 1979–1987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.09.023

Noll, J. G., & Shenk, C. E. (2013). Teen birth rates in sexually abused and neglected females. Pediatrics, 131(4), e1181–e1187. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3072

Pedagno, A. T. (2011). Who are the parents? In loco parentis, parens patriae, and abortion decision-making for pregnant girls in foster care. Ave Maria Law Review, 10(1), 171–202. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/avemar10&i=173

Peterson, J., Pearce, P. F., Ferguson, L. A., & Langford, C. A. (2017). Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12380

Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

Pleck, J. H. (2010). Paternal involvement: Revised conceptualizations and theoretical linkages with child outcomes. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Pokempner, J. (2019). Leveraging the FFPSA for older youth: Prevention provisions. Children’s Rights Litigation, 22(3), 17–22.

Pokempner, J. (2020). Know your rights guide: Tools for navigating the child welfare system and advocating for yourself (pp. 1–153). Juvenile Law Center. https://jlc.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2020-06/Know%20Your%20Rights%20Guide_Full%20Guide_0.pdf

Polit, D. F., Morton, T. D., & White, C. M. (1989). Sex, contraception and pregnancy among adolescents in foster care. Family Planning Perspectives, 21(5), 203. https://doi.org/10.2307/2135572