Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to identify and classify genetic variants in consensus moderate-to-high-risk predisposition genes associated with Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (HBOC), in BRCA1/2-negative patients from Brazil.

Methods

The study comprised 126 index patients who met NCCN clinical criteria and tested negative for all coding exons and intronic flanking regions of BRCA1/2 genes. Multiplex PCR-based assays were designed to cover the complete coding regions and flanking splicing sites of six genes implicated in HBOC. Sequencing was performed on HiSeq2500 Genome Analyzer.

Results

Overall, we identified 488 unique variants. We identified five patients (3.97%) that harbored pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in four genes: ATM (1), CHEK2 (2), PALB2 (1), and TP53 (1). One hundred and thirty variants were classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS), 10 of which were predicted to disrupt mRNA splicing (seven non-coding variants and three coding variants), while other six missense VUS were classified as probably damaging by prediction algorithms.

Conclusion

A detailed mutational profile of non-BRCA genes is still being described in Brazil. In this study, we contributed to filling this gap, by providing important data on the diversity of genetic variants in a Brazilian high-risk patient cohort. ATM, CHEK2, PALB2 and TP53 are well established as HBOC predisposition genes, and the identification of deleterious variants in such actionable genes contributes to clinical management of probands and relatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Antoniou A, Pharoah PDP, Narod S et al (2003) Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 72:1117–1130. https://doi.org/10.1086/375033

Maxwell KN, Domchek SM (2012) Cancer treatment according to BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 9:520–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.123

Easton DF, Pharoah PDP, Antoniou AC et al (2015) Gene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer risk. N Engl J Med 372:2243–2257. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1501341

Susswein LR, Marshall ML, Nusbaum R et al (2016) Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variant prevalence among the first 10,000 patients referred for next-generation cancer panel testing. Genet Med 18:823–832. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.166

Slavin TP, Maxwell KN, Lilyquist J et al (2017) The contribution of pathogenic variants in breast cancer susceptibility genes to familial breast cancer risk. NPJ Breast Cancer 3:22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-017-0024-8

Jarhelle E, Riise Stensland HMF, Hansen GÅM et al (2019) Identifying sequence variants contributing to hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 negative breast and ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep 9:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55515-x

Pal T, Agnese D, Daly M et al (2020) Points to consider: is there evidence to support BRCA1/2 and other inherited breast cancer genetic testing for all breast cancer patients? A statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med 22:681–685. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0712-x

Couch FJ, Hart SN, Sharma P et al (2015) Inherited mutations in 17 breast cancer susceptibility genes among a large triple-negative breast cancer cohort unselected for family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 33:304–311. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1414

Kurian AW, Li Y, Hamilton AS, et al (2017) Gaps in incorporating germline genetic testing into treatment decision-making for early-stage breast cancer. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. pp 2232–2239

Momozawa Y, Iwasaki Y, Parsons MT et al (2018) Germline pathogenic variants of 11 breast cancer genes in 7,051 Japanese patients and 11,241 controls. Nat Commun 9:4–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06581-8

Desmond A, Kurian AW, Gabree M et al (2015) Clinical actionability of multigene panel testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment. JAMA Oncol 1:943–951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2690

Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C et al (2017) Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 3:1190–1196. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0424

Rosenthal EA, Ranola JMO, Shirts BH (2017) Power of pedigree likelihood analysis in extended pedigrees to classify rare variants of uncertain significance in cancer risk genes. Fam Cancer 16:611–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-017-9989-6

Bonache S, Esteban I, Moles A et al (2018) Multigene panel testing beyond BRCA1/2 in breast/ovarian cancer Spanish families and clinical actionability of findings. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 144:2495–2513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2763-9

Hauke J, Horvath J, Groß E et al (2018) Gene panel testing of 5589 BRCA1/2-negative index patients with breast cancer in a routine diagnostic setting: results of the German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Med 7:1349–1358. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1376

Lu HM, Li S, Black MH et al (2019) Association of breast and ovarian cancers with predisposition genes identified by large-scale sequencing. JAMA Oncol 5:51–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2956

Singh J, Thota N, Singh S et al (2018a) Screening of over 1000 Indian patients with breast and/or ovarian cancer with a multi-gene panel: prevalence of BRCA1/2 and non-BRCA mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 170:189–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4726-x

Dominguez-Valentin M, Nakken S, Tubeuf H et al (2019) Results of multigene panel testing in familial cancer cases without genetic cause demonstrated by single gene testing. Sci Rep 9:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54517-z

Antoniou AC, Casadei S, Heikkinen T et al (2014) Breast-cancer risk in families with mutations in PALB2. N Engl J Med 371:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1400382

Schon K, Tischkowitz M (2018) Clinical implications of germline mutations in breast cancer: TP53. Breast Cancer Res Treat 167:417–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4531-y

Yang X, Leslie G, Doroszuk A et al (2019) Cancer risks associated with germline PALB2 pathogenic variants: an international study of 524 families. J Clin Oncol 38:674–685

Marabelli M, Cheng SC, Parmigiani G (2016) Penetrance of ATM gene mutations in breast cancer: a meta-analysis of different measures of risk. Genet Epidemiol 40:425–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21971

Eliade M, Skrzypski J, Baurand A et al (2017) The transfer of multigene panel testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer to healthcare: what are the implications for the management of patients and families? Oncotarget 8:1957–1971. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12699

Tung NM, Boughey JC, Pierce LJ et al (2020) Management of hereditary breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology Guideline. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00299

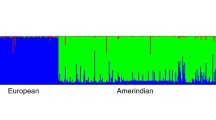

Pena SDJ, di Pietro G, Fuchshuber-Moraes M et al (2011) The genomic ancestry of individuals from different geographical regions of Brazil is more uniform than expected. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017063

Kehdy FSG, Gouveia MH, Machado M et al (2015) Origin and dynamics of admixture in Brazilians and its effect on the pattern of deleterious mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:8696–8701. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1504447112

Cybulski C, Kluźniak W, Huzarski T et al (2019) The spectrum of mutations predisposing to familial breast cancer in Poland. Int J Cancer 145:3311–3320. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32492

Achatz MIW, Olivier M, Le CF et al (2007) The TP53 mutation, R337H, is associated with Li-Fraumeni and Li-Fraumeni-like syndromes in Brazilian families. Cancer Lett 245:96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.039

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF (1988) A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 16:1215. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/16.3.1215

Castéra L, Krieger S, Rousselin A et al (2014) Next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer using genomic capture targeting multiple candidate genes. Eur J Hum Genet 22:1305–1313. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.16

Laduca H, Stuenkel AJ, Dolinsky JS et al (2014) Utilization of multigene panels in hereditary cancer predisposition testing: analysis of more than 2,000 patients. Gen Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.40

Thompson ER, Rowley SM, Li N et al (2016) Panel testing for familial breast cancer: calibrating the tension between research and clinical care. J Clin Oncol 34:1455–1459. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7454

NCCN (2014) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Breast Cancer. Version 1.2014

de Leeneer K, de Schrijver J, Clement L et al (2011) Practical tools to implement massive parallel pyrosequencing of PCR products in next generation molecular diagnostics. PLoS One 6:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025531

McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE et al (2016) The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol 17:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4

den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR et al (2016) HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Hum Mutat 37:564–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.22981

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S et al (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17:405–423. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.30

Meyer R, Kopanos C, Albarca Aguilera M et al (2018) VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty897

Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M et al (2009) Human splicing finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res 37:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp215

Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB (2003) DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 421:499–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01368

Pauty J, Couturier AM, Rodrigue A et al (2017) Cancer-causing mutations in the tumor suppressor PALB2 reveal a novel cancer mechanism using a hidden nuclear export signal in the WD40 repeat motif. Nucleic Acids Res 45:2644–2657. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx011

Wiltshire T, Ducy M, Foo TK et al (2020) Functional characterization of 84 PALB2 variants of uncertain significance. Genet Med 22:622–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0682-z

Decker B, Allen J, Luccarini C et al (2017) Rare, protein-truncating variants in ATM, CHEK2 and PALB2, but not XRCC2, are associated with increased breast cancer risks. J Med Genet 54:732–741. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104588

Antoniou AC, Pharoah PD, McMullan G et al (2001) Evidence for further breast cancer susceptibility genes in addition to BRCA1 and BRCA2 in a population-based study. Genet Epidemiol 21:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.1014

Girard E, Eon-Marchais S, Olaso R et al (2019) Familial breast cancer and DNA repair genes: Insights into known and novel susceptibility genes from the GENESIS study, and implications for multigene panel testing. Int J Cancer 144:1962–1974. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31921

Meijers-Heijboer H, Wijnen J, Vasen H et al (2003) The CHEK2 1100delC mutation identifies families with a hereditary breast and colorectal cancer phenotype. Am J Hum Genet 72:1308–1314. https://doi.org/10.1086/375121

Naseem H, Boylan J, Speake D et al (2006) Inherited association of breast and colorectal cancer: limited role of CHEK2 compared with high-penetrance genes. Clin Genet 70:388–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00698.x

Winship I, Southey MC (2016) Gene panel testing for hereditary breast cancer. Med J Aust 204:188-190.e1. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja15.01335

Delimitsou A, Fostira F, Kalfakakou D et al (2019) Functional characterization of CHEK2 variants in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae system. Hum Mutat 40:631–648. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23728

Fischer NW, Prodeus A, Gariépy J (2018) Survival in males with glioma and gastric adenocarcinoma correlates with mutant p53 residual transcriptional activity. JCI insight. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.121364

Singh J, Thota N, Singh S et al (2018b) Screening of over 1000 Indian patients with breast and/or ovarian cancer with a multi-gene panel: prevalence of BRCA1/2 and non-BRCA mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 170:189–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4726-x

Tavtigian SV, Oefner PJ, Babikyan D et al (2009) Rare, evolutionarily unlikely missense substitutions in atm confer increased risk of breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet 85:427–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.018

Buys SS, Sandbach JF, Gammon A et al (2017) A study of over 35,000 women with breast cancer tested with a 25-gene panel of hereditary cancer genes. Cancer 123:1721–1730. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30498

Sás D (2015) Mutações em genes de predisposição para câncer de mama em pacientes brasileiros de risco. Diss - Univ Estadual Paul “Julio Mesquita Filho”, Inst Biociências Botucatu 42

de Souza Timoteo AR, Gonçalves AÉMM, Sales LAP et al (2018) A portrait of germline mutation in Brazilian at-risk for hereditary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 172:637–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4938-0

Afghahi A, Kurian AW (2017) The Changing landscape of genetic testing for inherited breast cancer predisposition. Curr Treat Options Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-017-0468-y

Da Costa E, Silva Carvalho S, Cury NM, Brotto DB et al (2020) Germline variants in DNA repair genes associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome: analysis of a 21 gene panel in the Brazilian population. BMC Med Genom. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-019-0652-y

Dutil J, Golubeva VA, Pacheco-Torres AL et al (2015) The spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 alleles in Latin America and the Caribbean: a clinical perspective. Breast Cancer Res Treat 154:441–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3629-3

Dutil J, Teer JK, Golubeva V et al (2019) Germline variants in cancer genes in high-risk non-BRCA patients from Puerto Rico. Sci Rep 9:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54170-6

Jerzak KJ, Mancuso T, Eisen A (2018) Ataxia–telangiectasia gene (ATM) mutation heterozygosity in breast cancer: a narrative review. Curr Oncol 25:e176–e180. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.25.3707

Anna A, Monika G (2018) Splicing mutations in human genetic disorders: examples, detection, and confirmation. J Appl Genet 59:253–268

Fu Y, Masuda A, Ito M et al (2011) AG-dependent 3’-splice sites are predisposed to aberrant splicing due to a mutation at the first nucleotide of an exon. Nucleic Acids Res 39:4396–4404. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr026

Fortuno C, Cipponi A, Ballinger ML et al (2019) A quantitative model to predict pathogenicity of missense variants in the TP53 gene. Hum Mutat 40:788–800. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23739

Palmero EI, Carraro DM, Alemar B et al (2018) The germline mutational landscape of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Brazil. Sci Rep 8:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27315-2

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to all patients who participated in this study. We also thank Kelly Rose Lobo de Souza who performed BRCA genetic testing and Carolina Furtado for her experimental assistance. This work was supported by the National Institute for Cancer Control (INCT para Controle do Câncer; https://www.inct-cancer-control.com.br), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil, Grant Numbers: 305873/2014-8 and 573806/2008-0), and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ, Brazil Grant Number: E26/170.026/2008). PSS was supported by grants from the Rio de Janeiro State Science Foundation (FAPERJ E26/201.200/2014), the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq 304498/2014-9), and the Coordination for Higher Education Personnel Training (CAPES). This study is part of the requirements for the doctoral degree in Genetics of PSS at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: MAMM and CRB. Patients’ inclusion, clinical data collection, and Genetic Counseling: ACES. DNA sequencing: RG, PSS, CMN, SMAP and BPM. Identification of genetics variants and pathogenicity classification: RG, ACB, PSS, and BPM. Manuscript writing—original draft: RG. Manuscript writing—review and editing: RG, PSS, BPM, and MAMM. Funding acquisition: MAMM and CRB. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Patient consent

All individuals who participate in this study provided written informed consent approved by the local ethics committee. No identifiable personal patient data are show in this article.

Research involving human rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were approved by the ethical committee of the Brazilian National Cancer Institute (INCA; Project #114/07 and C.A.A.E. 14144819.0.0000.5274).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10549_2020_5985_MOESM2_ESM.eps

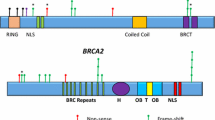

Supplementary file2 Supplementary Fig. 2 Pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), and VUS classified as probably damaging by protein position. Protein domains are shown as colored bars (EPS 3033 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gomes, R., Spinola, P.d., Brant, A.C. et al. Prevalence of germline variants in consensus moderate-to-high-risk predisposition genes to hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA1/2-negative Brazilian patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 185, 851–861 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05985-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05985-9