Abstract

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the leading cause of cancer death in Caribbean women. Across the Caribbean islands, the prevalence of hereditary breast cancer among unselected breast cancer patients ranges from 5 to 25%. Moreover, the prevalence of BC among younger women and the high mortality in the Caribbean region are notable. This BC burden presents an opportunity for cancer prevention and control that begins with genetic testing among high-risk women. Measured response to positive genetic test results includes the number of preventive procedures and cascade testing in family members. We previously reported data on an active approach to promote cascade testing in the Bahamas and report on preventive procedures showing moderate uptake. Here, we describe a clinically structured and community-partnered approach to the dissemination and follow-up of genetic test results including family counseling for the promotion of risk mitigation strategies and cascade testing in our Trinidadian cohort of patients tested positive for BC predisposition genes.

Methods

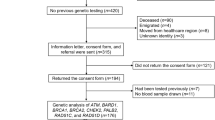

As a part of our initial study of BC genetic testing in Trinidad and Tobago, all participants received pre-test counseling including three-generation pedigree and genetic testing for BRCA1/2, PALB2, and RAD51C. The study was approved by the University of Miami IRB and the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health, Trinidad and Tobago. We prospectively evaluated a clinically structured approach to genetic counseling and follow-up of BC mutation carriers in Trinidad and Tobago in 2015. The intervention consisted of (1) engaging twenty-nine BC patients with a deleterious gene mutation (probands), and (2) invitation of their at-risk relatives to attend to a family counseling session. The session included information on the meaning of their results, risk of inheritance, risk of cancer, risk-reduction options, offering of cascade testing to family members, and follow-up of proband decision-making over two years.

Results

Twenty-four of twenty-nine mutation carriers (82.8%) consented to enroll in the study. At initial pedigree review, we identified 125 at-risk relatives (ARR). Seventy-seven ARR (62%) attended the family counseling sessions; of these, 76 ARR (99%) consented to be tested for their family gene mutation. Genetic sequencing revealed that of the 76 tested, 35 (46%) ARR were carriers of their family mutation. The ARR received their results and were urged to take preventative measures at post-test counseling. At 2-year follow-up, 6 of 21 probands with intact breasts elected to pursue preventive mastectomy (28.5%) and 4 of 20 women with intact ovaries underwent RRSO (20%).

Conclusions

In Trinidad and Tobago, a clinically structured and partnered approach to our testing program led to a significant rate of proband response by completing the intervention counseling session, executing risk-reducing procedures as well as informing and motivating at-risk relatives, thereby demonstrating the utility and efficacy of this BC control program.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Razzaghi H, Quesnel-Crooks S, Sherman R et al (2016) Leading causes of cancer mortality: Caribbean region, 2003–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65(49):1395–1400

Donenberg T, Ahmed H, Royer R et al (2016) A Survey of BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 mutations in women with breast cancer in Trinidad and Tobago. Breast Cancer Res Treat 159(1):131–138

Lerner-Ellis J, Donenberg T, Ahmed H et al (2017) A high frequency of PALB2 mutations in Jamaican patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 162(3):591–596

Donenberg T, Lunn J, Curling D et al (2011) A high prevalence of BRCA1 mutations among breast cancer patients from the Bahamas. Breast Cancer Res Treat 125(2):591–596

Naraynsingh V, Hariharan S, Dan D, Bhola S, Bhola S, Nagee K (2010) Trends in breast cancer mortality in Trinidad and Tobago: a 35-year study. Cancer Epidemiol 34(1):20–23

Hennis AJ, Hambleton IR, Wu SY, Leske MC, Nemesure B (2009) Barbados National Cancer Study G. Breast cancer incidence and mortality in a Caribbean population: comparisons with African-Americans. Int J Cancer 124(2):429–433

Camacho-Rivera M, Ragin C, Roach V, Kalwar T, Taioli E (2015) Breast cancer clinical characteristics and outcomes in Trinidad and Tobago. J Immigr Minor Health 17(3):765–772

Salhab M, Bismohun S, Mokbel K (2010) Risk-reducing strategies for women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations with a focus on prophylactic surgery. BMC Womens Health 10:28

Daly MB, Pilarski R, Berry M et al (2017) NCCN guidelines insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian, version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 15(1):9–20

Metcalfe KA, Lubinski J, Ghadirian P et al (2008) Predictors of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: the Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. J Clin Oncol 26(7):1093–1097

Metcalfe K, Gershman S, Ghadirian P et al (2014) Contralateral mastectomy and survival after breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: retrospective analysis. BMJ 348:g226

Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P et al (2014) Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 32(15):1547–1553

Forman AD, Hall MJ (2009) Influence of race/ethnicity on genetic counseling and testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Breast J 15(Suppl 1):S56–S62

Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M (2005) Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. JAMA 293(14):1729–1736

Lerman C, Hughes C, Benkendorf JL et al (1999) Racial differences in testing motivation and psychological distress following pretest education for BRCA1 gene testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8(4 Pt 2):361–367

Trottier M, Lunn J, Butler R et al (2016) Prevalence of founder mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes among unaffected women from the Bahamas. Clin Genet 89(3):328–331

Akbari MR, Donenberg T, Lunn J et al (2014) The spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients in the Bahamas. Clin Genet 85(1):64–67

Trottier M, Lunn J, Butler R et al (2015) Strategies for recruitment of relatives of BRCA mutation carriers to a genetic testing program in the Bahamas. Clin Genet 88(2):182–186

Narod SA, Butler R, Bobrowski D et al (2017) Short report: follow-up of Bahamian women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 6:301–304

Fashoyin-Aje L, Sanghavi K, Bjornard K, Bodurtha J (2013) Integrating genetic and genomic information into effective cancer care in diverse populations. Ann Oncol 24(suppl_7):vii48–vii54

Daly MB, Pilarski R, Axilbund JE et al (2014) Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian, version 1.2014. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 12(9):1326–1338

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W (1979) Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 41(3):209–218

Metcalfe KA, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Lubinski J et al (2008) International variation in rates of uptake of preventive options in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Int J Cancer 122(9):2017–2022

Wainberg S, Husted J (2004) Utilization of screening and preventive surgery among unaffected carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13(12):1989–1995

Flippo-Morton T, Walsh K, Chambers K et al (2016) Surgical decision making in the BRCA-positive population: institutional experience and comparison with recent literature. Breast J 22(1):35–44

Cragun D, Weidner A, Lewis C et al (2017) Racial disparities in BRCA testing and cancer risk management across a population-based sample of young breast cancer survivors. Cancer 123(13):2497–2505

Lieberman S, Lahad A, Tomer A et al (2018) Familial communication and cascade testing among relatives of BRCA population screening participants. Genet Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2018.26

Fehniger J, Lin F, Beattie MS, Joseph G, Kaplan C (2013) Family communication of BRCA1/2 results and family uptake of BRCA1/2 testing in a diverse population of BRCA1/2 carriers. J Genet Couns 22(5):603–612

MacDonald DJ, Blazer KR, Weitzel JN (2010) Extending comprehensive cancer center expertise in clinical cancer genetics and genomics to diverse communities: the power of partnership. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 8(5):615–624

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from Komen For the Cure. The authors thank the staff of the North West Regional Health Authority: Dr. Dylan Narinesingh, Dr. Cemonne Nixon, Dr. Jamie Morton-Gittens, Dr. Zahir Mohammed, Dr. Suzanne Chapman, Nurse Patrice Carrington, and Nurse Netasha Celestine.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Susan G. Komen Foundation (PI: Hurley).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TD: Conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft. SG: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. JA: Conceptualization, data collection, formal analysis, writing—review and editing GB: Formal analysis, writing—original draft. KH: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. NS: Data collection, writing—review and editing. KTA: Writing—review and editing. MRA: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. SAN: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. JH: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and Animal rights

This study did not involve animals.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Donenberg, T., George, S., Ali, J. et al. A clinically structured and partnered approach to genetic testing in Trinidadian women with breast cancer and their families. Breast Cancer Res Treat 174, 469–477 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5045-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5045-y