Abstract

Considerable effort has been devoted to the analysis of genotype by environment (G × E) interactions in various phenotypic domains, such as cognitive abilities and personality. In many studies, environmental variables were observed (measured) variables. In case of an unmeasured environment, van der Sluis et al. (2006) proposed to study heteroscedasticity in the factor model using only MZ twin data. This method is closely related to the Jinks and Fulker (1970) test for G × E, but slightly more powerful. In this paper, we identify four challenges to the investigation of G × E in general, and specifically to the heteroscedasticity approaches of Jinks and Fulker and van der Sluis et al. We propose extensions of these approaches purported to solve these problems. These extensions comprise: (1) including DZ twin data, (2) modeling both A × E and A × C interactions; and (3) extending the univariate approach to a multivariate approach. By means of simulations, we study the power of the univariate method to detect the different G × E interactions in varying situations. In addition, we study how well we could distinguish between A × E, A × C, and C × E. We apply a multivariate version of the extended model to an empirical data set on cognitive abilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The topic of genotype by environment (G × E) interaction has received increasing attention in the past decade in twin and family studies, and in (genome-wide) genetic association studies (GWAS). A G × E interaction denotes the degree to which the phenotypic variation explained by genetic factors varies across environmental conditions, or, conversely, the degree to which phenotypic variation explained by environmental influences varies across genotypes (see Boomsma and Martin 2002).

Using multi-group designs (Boomsma et al. 1999) or the moderation model proposed by Purcell (2002), various twin and family studies have shown that within the ACE-model, the phenotypic variance decomposition into additive genetic factors (A), common environmental factors (C) and unique environmental factors (E) varies across environmental conditions. This has been established with respect to various behavioral measures (e.g. aggression and alcohol consumption; see Kendler 2001, for a review including more examples) and specifically with respect to cognitive ability (Bartels et al. 2009a; Grant et al. 2010; Harden et al. 2007; Johnson et al. 2009a; Turkheimer et al. 2003; van der Sluis et al. 2008), personality (Bartels et al. 2009b; Boomsma et al. 1999; Brendgen et al. 2009; Distel et al. 2010; Heath et al. 1998; Hicks et al. 2009a; Hicks et al. 2009b; Johnson et al. 2009b; Silberg et al. 2001; Tuvblad et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2009), health-related phenotypes (Johnson and Krueger 2005; Johnson et al. 2010; McCaffery et al. 2008; McCaffery et al. 2009), and measures of brain morphology (Lenroot et al. 2009; Wallace et al. 2006).

In these studies, the extent to which the additive genetic factor A explains phenotypic variation fluctuates as a function of a specific measured environmental variable. It has, however, proven difficult to identify the (multiple) relevant environmental conditions that moderate the influence of genetic factors (e.g. Eichler et al. 2010). In GWAS, for example, G × E interaction is usually not modeled, although in theory, the presence of unmodeled G × E may affect the power to detect genetic variants (e.g. Eichler et al. 2010; Maher 2008; Manolio et al. 2009).

As the identification of environmental variables involved in G × E can be difficult, methods to detect G × E interactions given unmeasured genetic and environmental factors remain useful. At presence, two MZ-twin based methods are available. Letting Y 1 and Y 2 denote MZ twin pair scores, Jinks and Fulker (1970) showed that G × E may be detected in the dependency of |Y 1 − Y 2|, a proxy for the variance of E, on Y 1 + Y 2, a proxy for the level of A (see Jinks and Fulker 1970). In a similar approach, van der Sluis et al. (2006) used marginal maximum likelihood to test for heteroscedastic E variance by conditioning on A in MZ twin data (Hessen and Dolan 2009; Molenaar et al. 2010). Like Jinks and Fulker (1970), these authors focused on the detection of A × E, i.e. heteroscedastic E variance as a function of A.

In the following, we use the term ‘G × E’ to refer to the general concept of ‘genotype-by-environment interaction’. In addition, we refer to specific instances of G × E that are modeled in a given statistical model (e.g. A × E in the ACE model; A × M in the moderation model of Purcell 2002, where M is a measured variable).

Problems with existing heteroscedasticity approaches

The methods of Jinks and Fulker (1970) and van der Sluis et al. (2006) face a number of challenges. Here we address the following four: non-normality, conflation of A × E and C × E, heteroscedastic measurement error, and genotype–environment correlation.

Non-normality

As heteroscedasticity due to G × E results in non-normality of the observed phenotypic variable, other sources of non-normality can result in spurious G × E. These include floor and ceiling effects (see van der Sluis et al. 2006), poor scaling of the measurement (Eaves 2006; Evans et al. 2002) and non-linear factor-to-indicator relations (Tucker-Drob et al. (2009)).

Heteroscedastic measurement error

As discussed by Turkheimer and Waldron (2000), the statistical ‘unique environment factor’, E, is not necessarily equal to the conceptual notion of environmental influences underlying phenotypic scores, as the former may for instance include measurement error (see also Loehlin and Nichols 1976). This is a challenge as heteroscedastic measurement error may mimic G × E.

Conflation of A × E and C × E

The existing univariate approaches by Jinks and Fulker and van der Sluis utilize MZ twin data only. This precludes distinguishing between the additive genetic effects, A, and the common environment effects, C (Evans et al. 2002). It is therefore possible that an observed effect can be due to C × E rather than A × E.

Genotype–environment correlation

Measures of the environment that interact with A may themselves be affected by either the same or unique genetic influences (e.g. Turkheimer et al. 2009). Such genotype–environment correlation is known to affect tests using measured environments, in both the case that the genetic influences are unique and common to the measured environment and the phenotype (Purcell 2002). It is however unknown how it affects the heteroscedasticity approaches as presented above.

Note that the problems discussed above are not limited to the approaches of Jinks and Fulker and van der Sluis et al. in which the environment is unmeasured. Given measured environment, non-normality of the phenotypic variable can also result in spurious G × E (Purcell 2002). In addition, testing for G × E in presence of a genotype–environment correlation is a challenge in the measured moderator approach as well (see van der Sluis et al. 2011; Rathouz et al. 2008).

Towards a solution

In this paper, we address the problems mentioned above in an extended version of the approach of van der Sluis et al. Specifically, we extend the van der Sluis et al. method to include dizygotic (DZ) twin data to avoid the conflation of the A and C components. The inclusion of DZ data has several advantages: first, one can distinguish between A × E and A × C. Second, inclusion of DZ twin data will increase the power simply due to the increase in total sample size. Third, A × E effects may be detected more readily if the C component can be isolated. Finally, as A and C are separated, we hypothesize that the presence of C × E does not result in spurious A × E.

In addition to the extension of van der Sluis et al. (2006), we propose a multivariate extension. In the multivariate extension we use the common path way model to distinguish between the measurement model (a phenotypic one factor model) and the biometric model (McArdle and Goldsmith 1984; Kendler et al. 1987; Franić et al. 2011). In this model, genetic and environmental influences contribute to the observed phenotypic variance via one common phenotypic construct. In the measurement model, the observed phenotypic variables are linked to the latent phenotypic construct. In the biometric model, the latent phenotypic construct is decomposed into the A, C, and E components. In this way we can introduce the A × E and A × C interactions at the level of the construct, instead of at the level of the observed variable. We thereby avoid the conflation of measurement error with unique environment influences, as measurement error is now explicitly modeled in the measurement part of the model, and the unique environment factor is separately modeled at the level of the latent phenotypic construct. So we can introduce heteroscedastic residuals in the measurement model to account for floor, ceiling, and/or poor scaling effects, and test G × E at the level of the biometric model.

Below, we first shortly introduce the univariate method discussed by van der Sluis et al. (2006) to detect A × E interactions in MZ twin data. Next, we extend this model to an ACE-model with both A × E and A × C interactions. We then investigate the extended model in simulation studies. We investigate whether the method can properly distinguish the different interactions. In addition, we compare the power to detect the various interactions of the extended method to the power of the van der Sluis et al. (2006) approach. We also investigate whether we can distinguish between A × E/A × C on the one hand and C × E on the other hand. Furthermore, we compare the present method with unmeasured C and E factors to the approach of Purcell (2002) that makes use of measured environment variables. Next, we discuss an extension of the method to include multivariate data, and apply the multivariate extension to an IQ data set (Osborne 1980). We conclude the paper with a short discussion.

The univariate case

Van der Sluis’ model: AE

Van der Sluis et al. (2006) was limited to the AE model. Specifically, given N twin pairs:

where Y j denotes the phenotypic score of the j-th twin member (j = 1, 2), and A j and E j denote the zero mean additive genetic and unshared environmental factor, respectively. The parameter υ is the intercept (phenotypic mean) and a and e are regression coefficients (factor loadings).

Given the usual assumptions of the twin method, the MZ covariance matrix includes the elements:

To test for a possible A × E interaction, van der Sluis et al. (2006) proposed to test for heteroscedasticity of σ 2E , by testing whether σ 2E varied systematically over the values of factor A. They specified a parametric function between σ 2E and the score of the twins on A, i.e.

where ‘σ 2E |A’ denotes ‘σ 2E conditional on the level of A’. The exponential function, exp(.), is used to avoid negative variances (see also Bauer and Hussong 2009; Hessen and Dolan 2009; Molenaar et al. 2010). In the equation, β0 is a baseline parameter and β1 is a heteroscedasticity parameter, which models the dependency of σ 2E on A. If β1 = 0, the model reduces to the standard AE-model. The model may be extended to accommodate more complicated relations between σ 2E and A, e.g. σ 2E |A = exp(β0 + β1A + β2A2).

To fit the model to data, van der Sluis et al. used marginal maximum likelihood (Bock and Aitkin 1981). As A1 = A2 = A, the marginal log likelihood function contains a single integral over A, which may be approximated using a one-dimensional Gauss-Hermite quadrature approximation, i.e.

where g(A) is the normal density for factor A, f(.) is the bivariate normal density function for y 1 and y 2 , conditional on the level of A, with μ|A = ν + aA, and σ 2E |A given by Eq. 4, and cor(y1,y2)|A = 0. W g and N g are the g-th weight and node in the Gauss-Hermite quadrature approximation (e.g. Stroud and Secrest 1966). Van der Sluis et al. (2006) showed that the model performed well in terms of statistical power to detect the A × E interaction. Below we extend this model by the addition of the DZ twins.

ACE-model

In the classical twin model, including MZ and DZ twins, the phenotypic covariance matrix of the ACE model includes the elements:

where σ 2C is the shared environmental variance and ρA is 1 (MZ) or 0.5 (DZ). We now consider both A × E and A × C interactions. To introduce the A × E interaction, we proceed as above, i.e.

We now include the subscript j because A of twin 1 and 2 are distinct in DZ twins. We model A × C interaction as heteroscedastic C variance, conditional on A:

with

where γ0 and γ1 are the baseline and heteroscedasticity parameter, respectively (as in Eq. 7). If A × C is present, the covariance between C1 and C2 will vary as a function of A1 and A2. However, as required, the correlation between C1 and C2 will be 1 for every level of both A1 and A2. We model these A × C and A × E simultaneously, i.e. we estimate β1 and γ1 simultaneously. In the standard ACE-model without G × E, the distribution of the phenotypic scores of the twins and their co-twins is assumed to be a bivariate normal distribution (Fig. 1a). In case of G × E, the bivariate distribution of the data becomes skewed due to A × C (Fig. 1b) or A × E (Fig. 1c). As can be seen, the two types of interactions result in specific violations of bivariate normality. Specifically, the presence of a positive A × C interaction (γ1 > 0; C variance is increasing across A) results in an observed distribution that is skewed to the right, see Fig. 1b. Similarly for positive A × E, see Fig. 1c. In addition, a negative A × C interaction (γ1 < 0) or a negative A × E interaction (β1 < 0) results in left skew.

In this approach of modeling G × E we choose to model σ 2E and σ 2C as a function of a latent A factor. This is different from Purcell (2002) who modeled the factor loading of A as a function of observed E or C. We choose the former option as it connects better to the framework of Jinks and Fulker (1970) who define G × E as heteroscedastic E with respect to A (see also Evans et al. 2002).

With MZ and DZ twin data, the marginal log likelihood involves a double integral (i.e. over A1 and A2), which can be approximated using multivariate Gauss-Hermite quadratures. As we have two dimensions now, we have two sets of nodes, N 1g and N 2h , where g = 1, …, Q and h = 1, …, Q (the total number of nodes is therefore Q 2).

Standard two-dimensional Gauss-Hermite quadrature approximation assumes both dimensions (here A1 and A2) to be uncorrelated. We therefore transform the nodes N 1g and N 2h into N *1g and N *2h so that these transformed nodes have the proper correlations (i.e. 1 for MZ twins and 0.5 for DZ twins). Thus for the MZ twins we use

and for the DZ twins:

The likelihood function of the model is now given by

where h(.) is the multivariate normal distribution for A1 and A2, f() is the bivariate normal distribution of Y 1 and Y 2 with μ|A j = ν + σA × A j and

W g and W k are the same weights as in the AE model (see above). The conditional correlation between y 1 and y 2 is

Simulation study 1

With the present models in place, we studied how well we can detect the various types of interactions, and how well we can distinguish between them. In addition we investigated whether the presence of a C × E interaction will influence the detection of A × E and/or A × C.

Design

We simulated data according to three scenarios. In all scenario’s A, C, and E are continuous variables. In scenario I, named ‘A predominant’, explained phenotypic variances by the A, C, and E factor equaled approximately 50, 25 and 25%, respectively (in the absence of any G × E interaction). In scenario II, named ‘AC predominant’, explained variances equaled approximately 40, 40, and 20% for the A, C, and E factors, respectively. Finally, in scenario III, named ‘C predominant’, explained variances equaled 20, 60, and 20%.

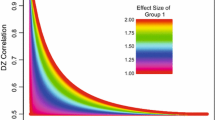

Within each scenario we simulated five different data sets. The first data set included an A × E interaction. The second data set included an A × C interaction. The third data set was simulated with both interactions (A × C and A × E) in the same direction, the fourth data set was simulated with both interactions in opposite direction, and the fifth data set included a C × E interaction. For each scenario, we additionally simulated a data set with no effect, i.e. according to the standard homoscedastic ACE-model. All data sets including an interaction effect were simulated to include either a small, a medium, or a large effect. We considered an interaction ‘small’ when the percentage of variance explained by the environmental factor in question increased with 3–4% for each standardized unit of A within the [−3; 3] interval. In the ‘medium’ condition, explained variance increased with 4–5% over the levels of A. In the ‘large’ condition explained variance increased with 5–6% over the levels of A. See Table 1 for the true values of the heteroscedasticity parameter, β1 and γ1. The other parameters equaled: σ 2A = 4, β0 = 0.45, and γ0 = 0.45 (scenario I), σ 2A = 4, β0 = 0.65, and γ0 = 1.40 (scenario II), and σ 2A = 2, β0 = 0.65, and γ0 = 1.70 (scenario III). See Fig. 2 for a graphical representation of the effect sizes across the scenarios.

For each condition in the design of the simulation study we simulated 1,000 data sets with 500 MZ and 500 DZ twin pairs. To each of these data sets, we fitted an ACE model: (1) with A × E interaction (ACE–AxE), (2) with A × C interaction (ACE–A × C), (3) with an A × E and an A × C interaction simultaneously (ACE–AxE–AxC), and (4) with A × E interaction using the MZ twin data only (AE–A × E). For each model, we calculated the power of the likelihood ratio test to detect the effects in the model (see Saris and Satorra 1993; Satorra and Saris 1985). See Molenaar et al. (2009) for an easy step-by-step illustration. All models were fitted in the freely available software package Mx (Neale et al. 2006). We used marginal maximum likelihood estimation (Bock and Aitkin 1981) with 100 multivariate Gauss-Hermite quadrature points (i.e. 10 for each dimension) to approximate both integrals in the likelihood function as discussed above. In case of the AE-model, we used 10 quadrature points as the likelihood function of this model only includes a single integral. Power was calculated using a 0.05 level of significance. All Mx input scripts are available from the website of the first author.

Results

In Table 1, parameter recovery is summarized for the cases in which the true model is fitted to the data (e.g. ACE–A × E when the data contains an A × E effect and ACE–A × E–A × C when the data contains both effects). In the Table 1, average parameter estimates of the G × E parameters, β1 and γ1 are shown together with their true values, standard deviation, and bias (which is defined as the difference between the average estimate and the true value divided by the true value). As appears from the Table 1, in case of an A × C effect in the data, the A × C parameter γ1 is somewhat underestimated within the ACE–A × C with percent bias between 15 and 29% in the three scenarios. In case of only an A × E effect in the data, the A × E parameter, β1, of the ACE–A × E is hardly biased with bias between 3 and 14%. In the case that both effects are in the opposite direction in the data, β1 is overestimated (bias between 20 and 37%), but γ1 is reasonably unbiased (bias between −11 and 22%). In the case that both effects are in the same direction in the data, β1 is somewhat biased in scenario I and II, but not biased in scenario III, and γ1 is severely biased in scenario I and II. The latter suggests that when both effects are in the same direction in scenario I and II, the A × C effect is absorbed to some degree by the A × E parameter β1.

Table 2 shows the power of the different models to detect the effects in scenario I (‘A predominant’). We only focus on scenario I to save space (as tables get really large) and because the main conclusions are the same for all scenario’s. However, power results of scenario II and III are available from the website of the first author. As can be seen in Table 2, in the absence of an effect, power coefficients approximately equal the level of significance (0.05). For example, when only an A × E is in the data, power to detect A × C should equal 0.05, as ideally the A × E effect in the data should not be detected as an A × C interaction. For all such cases, power coefficients are underlined in Table 2.

The underlined power coefficients in the Table 2 show that for each effect size, false positives are largely absent. That is, all power coefficients are close to 0.05 in the absence of an effect. Furthermore it can be concluded from the power coefficients that in the ACE–A × E–A × C model, the distinct interaction effects (A × E vs. A × C) are generally not confounded. However, in the ACE–A × E and ACE–A × C models, there is an increased risk on false positives. Specifically, the ACE–A × E model has an increased power to detect the A × C effect, and the ACE–A × C model has an increased power to detect the A × E effect.

If we consider the power to detect the effects that are actually in the data (i.e. the power coefficients that are not underlined in Table 2), we can conclude that within the ACE-models, the power to detect an A × E interaction is generally acceptable. For the ACE–A × E–A × C model, power is good for a large effect size (0.92), power is acceptable for a medium effect size (0.81), and moderate for a small effect size (0.61). Power to detect A × C interaction using the different models is far lower than the power to detect A × E. That is, large sample sizes are needed to detect the A × C effect. For the ACE–A × E–A × C model, power to detect A × C is at most 0.32 in case of a large effect size, while it is 0.92 for A × E. However, if the A × C interaction is accompanied by an A × E interaction in the opposite direction, effects are somewhat easier to resolve with power of at most 0.70.

We now compare the results of the models including data for both MZ and DZ twins with the AE-model, which includes data of MZ twins only. As the previous analysis involved a total of 1,000 subjects, we calculated the power of the AE-model to detect the interactions in the data in case of 1,000 MZ twins. In this case, power is approximately equal to the ACE–A × E model.

Finally, from Table 2 we conclude that the presence of a C × E interaction results in an increased false positive rate in detecting A × E. Specifically, given a small effect size, the ACE–A × C–A × E model has a power of 0.30 to detect an A × E interaction, while a C × E interaction is in the data. This power coefficient could be compared to the case that there truly is an A × E interaction in the data. In that comparison, this model has a power of 0.61 to detect an A × E effect. Thus, from Table 2 it can be seen that in scenario I for all effect sizes, power to detect A × E is larger when A × E is present than when C × E is present, which is reasonably acceptable. However, with respect to scenario II and III (not tabulated), results are somewhat different: in scenario II, where C explains more variance, the power to detect an A × E interaction is about equal when A × E is in the data and when C × E is present, for all effect sizes. In scenario III where C is the predominant factor, power to detect an A × E interaction is even larger when C × E is present than when A × E is in the data.

Conclusion

Overall, the power to detect an A × E interaction is acceptable. In contrast, to detect an A × C interaction, large sample sizes are needed as the power is low. This appears to be mainly due to underestimation of the A × C parameter, particularly in the case that A × C and A × E effects are both present in the same direction. However, results show that it could be important to take the A × C effect into account as it will increase the power to detect an A × E interaction. Within the ACE model, it is thus advisable to use the ACE–A × E–A × C model when one has no idea whether the interaction is A × E or A × C. Using the ACE–A × E or the ACE–A × C model can lead to an increased false positive rate (i.e. an A × C may be detected as an A × E, while A × E is absent).

Besides the underestimation of A × C, it appeared that the A × E effect could in some cases be somewhat overestimated. However, this is not a main problem as it appeared from the power study that the A × E effect is not associated with false positives. That is, when there is no A × E effect in the data, no spurious A × E effect arise.

From the simulation it is also clear that one can distinguish relatively well between A × E and A × C. However it is difficult to distinguish between A × E and C × E, particularly when C is a relatively large source of variation. If a C × E interaction is present, it may be mistakenly detected as an A × E interaction. We return to this point in the discussion.

Simulation study 2

In simulation study 2 we investigate the relation between the present approach with unmeasured environment, and the G × E approach where the environment is measured (Purcell 2002). First, it is interesting to see how interactions between genotypes and measured environment are detected in the ACE–A × E–A × C model, and second it is interesting to see how the ACE–A × E–A × C model deals with G × E interactions where the environment is open to genetic influences as well. To investigate this, we simulated data according to an ACE-model in which the A component is moderated by a measured environment variable. We distinguish between two cases (1) univariate moderation, in which the environment moderates the genetic variance unique to the phenotype of interest (i.e. the moderator may be influenced by genes, but these genes are not shared with the phenotype of interest), (2) bivariate moderation, in which the environment moderates the genetic variance common to the moderator and the phenotype of interest (i.e. the moderator is influenced by the same genes as the phenotypic variable resulting in a G × E correlation). Purcell (2002) proposed a model for both cases, which we refer to as the univariate and bivariate moderation model, respectively. We considered both the univariate model and the bivariate model, and fitted the ACE–A × E–A × C model to it to see whether the moderation effects are detected and how the gene by environment correlation influences the results.

Design univariate moderation

We simulated data according to an ACE-model, in which the A component was moderated by an external variable, M, i.e. (omitting subject and twin subscript)

where M is the (mean-centered) moderator, i.e. a measure of the environment, a 0 is the baseline parameter, a 1 is the moderation parameter, and parameter m takes into account the main effect of M (which is advisable when modeling interactions, see Nelder 1994). If a 1 departs from 0, A is moderated by M, which amounts to an A × E interaction. In the present simulation study we choose: a 0 = c = e = 1. In addition, we choose the main effect of the moderator to be to be either small (m = 0.5), medium (m = 0.75), or large (m = 1.0). Note that the main effect of the moderator is the same across the MZ and DZ twins (i.e. a C moderator). In addition, we chose the degree of moderation, to be small (a 1 = 0.5), medium (a 1 = 0.75), or large (a 1 = 1). Finally, we manipulated the within twin correlation of M to be either 0, 0.5, 0.7, or 1.0). As we are not interested in the exact power of the ACE–A × E–A × C model to detect the effects, effect sizes do not necessary reflect realistic effect sizes. The main aim of this simulation study is to see whether the moderation effects are detected by the ACE–A × E–A × C model. Note that we simulated the data using the observed moderator variable, but in fitting the ACE–A × E–A × C model, we do not use this variable.

Results univariate moderation

Table 3 shows the power to detect A × E in the presence of A × C and the power to detect A × C in the presence of A × E. Given these results, we note that when the within twin correlation of the moderator is 0 or 0.5, power to detect A × E is generally large, while the power to detect A × C is small. This indicates that the moderation effect in the data is generally detected as A × E. When the correlation increases to 0.7 or 1.0, power to detect A × E is small, and power to detect A × C is large, i.e. in this case the moderation effect in the data is generally detected as A × C. These results hold irrespective of the size of the main effect of the moderator. Power of the Purcell model equaled 1 in nearly all simulated scenarios (not tabulated). Power of the Purcell model is thus larger than the power in the ACE–A × E–A × C model, but this is not surprising as this approach uses the information available in the moderator variable.

Design bivariate moderation

As noted in Purcell (2002) the moderator could share genetic influences with the phenotypic variable, we denote these common influences, Ac. Purcell proposes the following model for the mean-centered M and Y:

i.e. the phenotypic variance is decomposed into A c , C c , and E c components which are shared with the moderator variable, and into A u , C u , and E u components which are unique to the phenotypic variable. Note that the model could be extended to introduce moderation of the C c and E c . When only the A u component is moderated, the univariate moderation model from Eq. 16 will suffice.

We simulated data according to the bivariate moderation model. We manipulated the effect size of the G × E effect into no effect (a 1 = 0), a small effect (a 1 = 0.5), a medium effect (a 1 = 0.75), and a large effect (a 1 = 1.0). In addition, we manipulated the size of the G × E correlation, into 0.3 (i.e. a m = 0.5), 0.4 (a m = 0.75) and 0.5 (a m = 1). We simulated an ‘E moderator’, that is, besides the effects of A, the moderator was influenced by E but not by C (c m = 0, e m = 1). The other parameters equaled c c = e c = c u = a 0 = a u = e u = 1. We note again that the chosen effect sizes are not necessarily realistic as we are only interested in how the ‘Purcell’ effects are detected in the ACE–A × E–A × C model.

Results bivariate model

Table 4 shows the power of the ACE–A × E–A × C model to detect A × E and A × C effects in the data under the different scenarios. We see that the moderation effect in the data is mainly detected as A × E (i.e. power of A × E effect is large, power of A × C effect is small). This was to be expected as the moderator was not influenced by C. In addition, we see that in case of no moderation in the data, no G × E is detected (i.e. power approaches 0.05 in all these cases). Thus, the G × E correlation does not appear to cause spurious interactions.

Conclusion and discussion

This second simulation study showed two important results. First, a correlation between phenotype and environment due to shared genes does not affect the results concerning tests on G × E in the ACE–A × E–A × C model. Second, interactions between observed measures of the environment and the additive genetic factor, A, can in principle be detected using the ACE–A × E–A × C model. Depending on the within twin correlation of the moderator, the interaction will arise as an A × E or A × C. Of course power is an issue here, as small effects will possibly remain undetected. However, given a sufficiently large sample size, phenotypic variables can be screened on G × E when no explicit hypotheses exist on which measures of the environment will interact with genetic influences of the phenotype, or when the relevant environment measures are not available (e.g. an IQ datasets which lacks a measure of SES).

Application

We applied the univariate G × E model to the Osborne data (Osborne 1980), which comprise scores of 477 twin pairs on various tests of cognitive ability. We analyzed the scores of the twin pairs on the first-principal component of 13 cognitive ability tests from the Osborn data. We found the ACE–A × E model to provide the best model fit, indicating that an A × E interaction is present in these data. We do not present the detailed results in this paper to save space, and because we apply the multivariate model to these data below. However, a small report of this application is available from the site of the first author.

The multivariate case

In this section, we introduce a multivariate approach in which we distinguish between a measurement model and a biometrical model (the common pathway model). In the biometrical part of the model, we introduce the A × C and A × E effects, and in the measurement model we introduce heteroscedastic residuals to account for possible heteroscedastic measurement error, and/or floor, ceiling, and poor scaling effects. In addition, we show how one can test for non-linear factor loadings within the multivariate approach. We outline the multivariate approach below.

Let y 1 denote the N × p-dimensional matrix of the scores of the N twin 1 members on p phenotypic scores, and let y 2 denote the scores of the twin 2 members. These scores are submitted to a k dimensional factor model which is referred to as the measurement model. In the measurement model, the observed variables are linked to a (set of) phenotypic construct(s). Specifically, the covariance matrix Σ y1, y2 of the horizontally stacked matrices y 1, y 2 is modeled as

where Λ are the factor loadings, Σ η is the covariance matrix of the phenotypic constructs, and Σθ is the covariance matrix of the residuals. The structure of the factor loading matrix, Λ, may be derived from theory, such as the general intelligence theory by Spearman (1904), or the Big Five personality theory (Digman 1990). In principle, Λ can be submitted to a Cholesky decomposition to test for general and specific genetic and environmental contributions, however then, the measurement model is not separated from the biometric model anymore. Here, we focus on a theory based factor model, but we return to the Cholesky decomposition in the discussion.

As an illustration, we consider general intelligence or g (Spearman 1904). According to g theory, a single phenotypic latent construct underlies all scores of a given intelligence test. That is, in both the twin 1 and 2 samples, we postulate one common factor. Given four observed cognitive variables, we have the following factor loading matrix:

where the factor loadings of the first variables of each twin are fixed to 1 for identification purposes.

In the biometric model, the 2 × 2 covariance matrix of the phenotypic constructs, Σ η , is decomposed as follows

i.e. the covariance matrix of the general intelligence factor underlying the twin 1 and 2 subtest data is modeled as a function of the A, C, and E factors.

To model A × C and A × E interactions, we can apply the univariate method from Eqs. 7 and 8 to the matrices ΣC, and ΣE, i.e.

and

where ‘|A1, A2’ means that the corresponding covariance matrix is conditional on both A1 and A2. The term on the off-diagonal of ΣC|A1, A2 ensures that the correlation between factor C1 and factor C2 remains equal to 1. For the general intelligence factor, we thus have two heteroscedasticity parameters, β1 and γ1 for the A × E and A × C interaction, respectively. Note that when there are multiple factors (e.g. in applications to Big Five personality data), each factor is associated with it’s own β1 and γ1 parameters.

Now, in the measurement model, we introduce heteroscedastic residual variances in Σθ to account for heteroscedasticity that is specific to the observed phenotypic variables and not due to heteroscedasticity of E or C on the level of the latent phenotypic construct, thus:

In this equation, δ01 is the baseline parameter for phenotypic variable 1, δ04 is the baseline parameter for phenotypic variable 4, δ11 is the heteroscedasticity parameter for phenotypic variable 1, etc. In addition, σθ1|A1,A2 is the conditional residual covariance between the scores of twin 1 and 2 on phenotypic variable 1, and σθ4|A1, A2 is the conditional residual covariance between the scores of twin 1 and 2 on phenotypic variable 4. These conditional covariances account for possible genetic and environment influences on the level of the residuals. These covariances could in principle be submitted to an ACE-decomposition, including A × E and/or A × C effects on the level of the individual variable. This would enable a test on whether G × E occurs at the level of the phenotypic construct or at the level of the individual variable. However, these G × E tests on the level of the variable are vulnerable to problems like poor scaling. For present purposes (testing G × E on the level of the phenotypic construct to avoid problems like poor scaling) we do not distinguish between ACE-components on the level of the variable. Instead, we account for similarities between twins of the same twin pair by conditional covariances between the residuals as introduced in Eq. 24. The conditional covariances are calculated as follows, e.g. for variable 1,

where ρ1 is the residual correlation between the twin 1 and 2 scores on variable 1 after the phenotypic construct is taken into account. Note that this correlation is constant across A1 and A2. Thus, to conclude, in the measurement model 15 parameters are estimated: λ1–λ3, and δ01–δ04, δ11–δ14, and ρ1–ρ4.

In the model above, we introduced heteroscedasticity in the biometric model to model A × E and A × C and we introduced heteroscedasticity in the measurement model to model heteroscedastic residuals. As the G × E effects are modeled on the factor that is common to all phenotypic variables (i.e. the phenotypic construct), the A × E and A × C effects capture the heteroscedasticity that is common to all variables of the construct. Variable specific heteroscedasticity (i.e. not shared among all variables) is captured by the heteroscedastic residuals. In doing so, confounds specific to the variables-like poor scaling are absorbed by the heteroscedastic residuals. The G × E effects that arise on the level of the construct can therefore be more confidently interpreted as such. However, as Eaves (2006) pointed out, the same artifacts of scale could be present in all variables in a G × E study. In the present approach, this may give rise to spurious G × E on the level of the construct.

Testing for spurious G × E due to non-linearity

The measurement model in Eq. 19 is based on the premise that the observed phenotypic scores are linearly predicted from the latent phenotypic construct. Tucker-Drob et al. (2009) showed that when the relation between the observed phenotypic variables and the latent phenotypic construct is non-linear, this can result in spurious G × E. To exclude possible spurious G × E we can test the factor loadings on non-linearity. Note that we test for non-linearity in the measurement model, but still retain the ACE decomposition in the biometric model. Testing for non-linearity of the factor loadings is straightforward in Mx (Neale et al. 2006; see Molenaar et al. 2010 for an Mx example) and Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2007; see Tucker-Drob et al. 2009 for an Mplus example).

Application

Data

We analyzed the Osborne data (Osborne 1980), which include the scores of 328 Caucasian twin pairs and 149 Afro–American twin pairs on various tests of cognitive abilities. As sample size within both groups is insufficient, we analyzed both groups together for illustrational purposes. The 477 twin pairs included 247 MZ twins (110 males, 137 females), and 230 DZ twins, of which 180 were same sex twins (65 male–male, 115 female–female) and 50 were opposite sex twins. Mean age was 15.30 (sd: 1.55; min: 12; max: 20).

From the Osborne data, we selected four subtests, the Mazes test, Object apeture test, Simple arithmetic test, and New castle spatial test that fitted a one-factor model well. To the scores of the twin 1 and 2 samples on these subtests, we fitted a one-factor model representing the general intelligence factor. The variance of this latent phenotypic factor was decomposed into an A, C, and E component, with A × E and A × C interactions, as in Eqs. 22, 23. In the full sample (i.e. MZs and DZs together), the scores were standardized to have variances equal to 4 to facilitate parameter estimation. See Table 5 for the correlation matrices in the MZ and DZ samples. The baseline model without A × E and A × C interaction fitted adequately compared to the saturated model [χ2(66) = 51.57]. In this model, the phenotypic factors correlated 0.76 (SE = 0.04) between the members of the DZ twins, and 0.95 (SE = 0.01) between the members of the MZ twins.

Results

First, we tested the factor loadings in the measurement model for non-linearity. We did this using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2007). Parameter estimates and model fit statistics are in Table 6. According to the AIC, BIC, and LRT, the model with non-linear factor loadings fitted best. However, only subtest OA is associated with a non-linear factor loading. As the effect concerns only a single variable, we continue our analysis assuming linearity for all variables for illustrational purposes. However, we stress that in practice one should be cautious drawing conclusion on G × E in the presence of unmodeled non-linearity. We return to this point in the discussion.

In Table 7, the results of the multivariate analyses are summarized. We started with the full model, the ACE–A × E–A × C–het, where ‘het’ denotes that heteroscedastic residuals are present (δ11–δ14 are estimated). In this model, the A × E and A × C effects are on the level of the general intelligence factor. From the model we dropped the A × C interaction. All model fit indices indicated that the model fit improved, indicating that an A × C interaction was absent [χ2(1) = 1.50]. Next, we dropped the A × E interaction from the model (resulting in an ACE–het model). All fit statistics indicated that the model fit deteriorated [χ2(1) = 9.23]. We thus concluded that the ACE–AxE–het model was a better fitting model. Parameter estimates of this model are in Table 8. As can be seen, the heteroscedasticity parameters of the residuals (δ11–δ14) did not differ significantly form 0, as judged by their confidence intervals. We therefore dropped these parameters, resulting in an ACE–A × E model. According to a likelihood ratio test, this model fitted better than a model with heteroscedastic residuals [χ2(4) = 6.158], this was confirmed by the AIC and BIC (see Table 7). Parameter estimates of the ACE–A × E, are in Table 8. It appears that dropping the heteroscedastic residuals (parameter δ11–δ14) hardly affected the A × E parameter, β1. The estimate of β1 changed from 1.40 to 1.38. As the estimate of β1 was larger than zero, the variance of factor E increases with increasing levels of factor A. Thus, for increasing genetic levels (i.e. for an increasing position on the additive genetic factor, A), differences between twins in phenotypes are larger because differences in environments increase. Note that this is consistent with the notion of ability differentiation in which the general intelligence factor is hypothesized to be a weaker source of individual differences at higher levels of this factor (Deary et al. 1996). This is similar to what we found in the univariate application where we used PC1 scores (as described shortly above). However, the advantage of the multivariate approach is that it enables us to show that the A × E effect involves the common phenotypic factor and is not due to heteroscedastic residuals.

Conclusion

In this paper we identified four challenges to the detection of G × E using the existing univariate heteroscedastic approaches of Jinks and Fulker (1970) and van der Sluis et al. (2006); non-normality, conflation of A × E and C × E, heteroscedastic measurement error, and gene by environment correlation. We presented an extension of the heteroscedasticity approach meant to overcome these problems. Specifically, we presented a univariate method suitable to study the presence of A × C and A × E interactions using both MZ and DZ twin data. In this approach, we explicitly distinguished between the A and C component so as to avoid the conflation of A and C. We showed that A × E and A × C interactions are well separable, but it turned out that A × E analyses are still influenced by the presence of C × E. One might argue that this problem could be solved by constructing a model that incorporates both A × E and C × E interaction simultaneously, so that the effects can be disentangled. We considered such a model, in which the variance of E was modeled as a function of both A and C. (Note that this simultaneous modeling of A × E and C × E requires an extension of the ACE-model that is not covered by the equations in the present paper). Simulations demonstrated that, although the extended model could be specified and fit without problems, A × E and C × E could not be distinguished. Specifically, when the simulated effect, e.g. A × E, was dropped, the likelihood hardly changed because the effect was almost fully absorbed by the C × E effect. Details about this extended model and the simulations are in the Appendix.

The difficulty of distinguishing A × E and C × E is related to the well known problem that A and C are less well resolvable compared to A and E, or C and E (Martin et al. 1978). The simulations that we presented show that the presence of C × E will bias tests of A × E, depending on the strength of C as a source of individual differences. For some phenotypic measures, it is known that the strength of C is negligibly small, specifically in cognitive abilities from adolescence onwards (see Boomsma et al. 2002). In these cases, A × E interactions may arguably be interpreted as such. In cases that C is substantial (i.e. situations comparable to scenario II and III from the simulations), one should be more careful in interpreting a significant A × E interaction, as the effect could indicate the presence of C × E rather than A × E. In such cases, it seems wise to interpret A × E as the interaction between familiarity factors and environmental factors, as in the analysis of MZ twin data only (as in Jinks and Fulker 1970; van der Sluis et al. 2006). That is, one leaves unresolved the exact dimension across which the strength of the environmental factor increase, i.e. A or C. A possible solution proposed by Jinks and Fulker (1970) is to consider twin data that includes MZ twins who are reared apart. In theory this improves the distinction of A and C. However, in practice such data are scarce. Nevertheless, the model could be useful as an explorative tool to screen phenotypic variables on G × E when no ideas exist (yet) on what measures to include in a Purcell (2002) type of analysis.

Extending the univariate approach of van der Sluis et al. (2006) to include DZ twins did not solve the conflation of A × E with C × E. However, this does not disqualify our new model as an approach of testing G × E. We think that the new method has some clear advantages over existing approaches. First, in our new method we can distinguish between A × E and A × C (although large samples or large effect sizes are needed to detect A × C). Second, because of the increased sample size due to the addition of the DZ twin data, power to detect A × E is increased as compared to the van der Sluis et al. and Jinks and Fulker model. Third, in both the simulation and application we showed that taking into account A × C interaction which is possible due to the DZ twin data, may be beneficial in terms of the power to detect the A × E effect.

References

Bartels M, Boomsma DI (2009) Born to be happy? The etiology of subjective well-being. Behav Genet 39:605–615

Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Boomsma DI (2009) Breast feeding, maternal education, and cognitive function: a prospective study in twins. Behav Genet 39:616–622

Bauer DJ, Hussong AM (2009) Psychometric approaches for developing commensurate measures across independent studies: traditional and new models. Psychol Methods 2:101–125

Bock RD, Aitkin M (1981) Marginal maximum likelihood estimation of item parameters: application of an EM algorithm. Psychometrika 46:443–459

Boomsma DI, Martin NG (2002) Gene–environment interactions. In: D’haenen H, den Boer JA, Willner P (eds) Biological psychiatry. Wiley, New York, pp 181–187

Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC, van Baal GCM, Koopmans JM (1999) A religious upbringing reduces the influence of genetic factors on disinhibition: evidence for interaction between genotype and environment on personality. Twin Res 2:115–125

Boomsma DI, Vink JM, van Beijsterveldt TC, de Geus EJ, Beem AL, Mulder EJ, Derks EM, Riese H, Willemsen GA, Bartels M, van den Berg M, Kupper NH, Polderman TJ, Posthuma D, Rietveld MJ, Stubbe JH, Knol LI, Stroet T, van Baal GC (2002) Netherlands twin register: a focus on longitudinal research. Twin Res 5:401–406

Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Boivin M, Girard A, Bukowski WM, Dionne G et al (2009) Gene–environment interplay between peer rejection and depressive behavior in children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:1009–1017

Deary IJ, Egan V, Gibson GJ, Austin E, Brand CR, Kellaghan T (1990) Intelligence, the differentiation hypothesis. Intelligence 23:105–132

Digman JM (1990) Personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model. Annu Rev Psychol 41:417–440

Distel MA, Rebollo-Mesa I, Abellaoui A, Derom CA, Willemsen G, Cacioppo JT, Boomsma DI (2010) Family resemblance for loneliness. Behav Genet 40:480–494

Eaves LJ (2006) Genotype x environment interaction in psychopathology: fact or artifact? Twin Res Hum Genet 9:1–8

Eichler EE, Flint J, Gibson G, Kong A, Leal SM, Moore JH, Nadeau JH (2010) Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat Rev Genet 11:446–450

Evans DM, Gillespie NA, Martin NG (2002) Biometrical genetics. Biol Psychol 1–2:33–51

Franić S, Dolan CV, Borsboom D, Hudziak JJ, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Boomsma DI (2011) Can genetics help psychometrics? Improving dimensionality assessment through genetic factor modeling (submitted)

Grant MD, Kremen WS, Jacobson KC, Franz C, Xian H, Eisen SA et al (2010) Does parental education have a moderating effect on the genetic and environmental influences of general cognitive ability in early adulthood? Behav Genet 40:438–446

Harden KP, Turkheimer E, Loehlin JC (2007) Genotype by environment interaction in adolescents’ cognitive aptitude. Behav Genet 37:273–283

Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Martin NG (1998) Interaction of marital status and genetic risk for symptoms of depression. Twin Res 1:119–122

Hessen DJ, Dolan CV (2009) Heteroscedastic one-factor models and marginal maximum likelihood estimation. Br J Math Stat Psychol 62:57–77

Hicks BM, DiRago AC, Iacono WG, McGue M (2009a) Gene–environment interplay in internalizing disorders: consistent findings across six environmental risk factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:1309–1317

Hicks BM, South SC, DiRago AC, Iacono W, McGue M (2009b) Environmental adversity and increasing genetic risk for externalizing disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:640–648

Jinks JL, Fulker DW (1970) Comparison of the biometrical genetical, mava, and classical approaches to the analysis of human behavior. Psychol Bull 73:311–349

Johnson W, Krueger RF (2005) Genetic effects on physical health: lower at higher income levels. Behav Genet 35:579–590

Johnson W, Deary IJ, Iacono WG (2009a) Genetic and environmental transactions underlying educational attainment. Intelligence 37:466–478

Johnson W, McGue M, Iacono WG (2009b) School performance and genetic and environmental variance in antisocial behaviour at the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Dev Psychol 45:973–987

Johnson W, Kyvik KO, Mortensen EL, Skytthe A, Batty GD, Deary IJ (2010) Education reduces the effects of genetic susceptibilities to poor physical health. Int J Epidemiol 39:406–414

Kendler KS (2001) Twin studies of psychiatric illness: an update. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:1005–1014

Kendler KS, Heath AC, Martin NG, Eaves LJ (1987) Symptoms of anxiety and depression: same genes, different environments? Arch Gen Psychiatry 44:451–457

Lenroot RK, Schmitt JE, Ordaz SJ, Wallace GL, Neale MC, Lerch JP et al (2009) Differences in genetic and environmental influences on the human cerebral cortex associated with development during childhood and adolescence. Hum Brain Mapp 30:163–174

Loehlin JC, Nichols PL (1976) Heredity, environment, and personality: a set of 850 twins. University of Texas Press, Austin

Maher B (2008) The case of the missing heritability. Nature 456:18–21

Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA et al (2009) Finding the missing heritability for complex diseases. Nat Rev Genet 461:747–753

Martin NG, Eaves LJ, Kearsey MJ, Davies P (1978) The power of the classical twin design. Heredity 40:97–116

McArdle J, Goldsmith HH (1984) Structural equation modeling applied to the twin design: comparative multivariate models of the WAIS. Behav Genet 14:609

McCaffery JM, Padandonatos GD, Lyons MJ, Niaura R (2008) Educational attainment and the heritability of self-reported hypertension among male Vietnam-era twins. Psychosom Med 70:781–786

McCaffery JM, Padandonatos GD, Bond DS, Lyons MJ, Wing RR (2009) Gene × environment interaction of vigorous exercise and body mass index among male Vietnam-era twins. Am J Clin Nutr 89:1011–1018

Molenaar D, Dolan CV, Wicherts JM (2009) The power to detect sex differences in IQ test scores using multi-group covariance and mean structure analysis. Intelligence 37:396–404

Molenaar D, Dolan CV, Verhelst ND (2010) Testing and modeling non-normality within the one factor model. Br J Math Stat Psychol 63:293–317

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2007) Mplus user’s guide, 5th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA

Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH (2006) Mx: statistical modeling, 7th edn. VCU, Department of Psychiatry, Richmond

Nelder JA (1994) The statistics of linear models: back to basics. Stat Comput 4:221–234

Osborne RT (1980) Twins: black and white. Foundation for Human Understanding, Athens

Purcell S (2002) Variance components models for gene–environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Res 5:554–571

Rathouz PJ, van Hulle CA, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID, Lahey BB (2008) Specification, testing, and interpretation of gene-by-measured-environment models in the presence of gene–environment correlation. Behav Genet 38:301–315

Saris WE, Satorra A (1993) Power evaluations in structural equation models. In: Bollen KA, Long JS (eds) Testing structural equation models. Sage, Newbury Park, pp 181–204

Satorra A, Saris WE (1985) The power of the likelihood ratio test in covariance structure analysis. Psychometrika 50:83–90

Silberg JL, Rutter M, Neale MC, Eaves LJ (2001) Genetic moderation of environmental risk for depression and anxiety in adolescent girls. Br J Psychiatry 179:116–121

Spearman C (1904) “General intelligence” objectively determined and measured. Am J Psychol 15:201–293

Stroud AH, Secrest D (1966) Gaussian quadrature formulas. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Tucker-Drob EM, Harden KP, Turkheimer E (2009) Combining nonlinear biometric and psychometric models of cognitive ability. Behav Genet 39:461–471

Turkheimer E, Waldron M (2000) Nonshared environment: a theoretical, methodological, and quantitative review. Psychol Bull 1:78–108

Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldorn M, D’Onofrio B, Gottesman II (2003) Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychol Sci 14:623–628

Turkheimer E, Harden KP, D’Onofrio B, Gottesman II (2009) The Scarr Rowe interaction between measured socioeconomic status and the heritability of cognitive ability. In: McCartney K, Weinberg RA (eds) Experience and development: a festschrift in honor of Sandra Wood Scarr. Psychology Press, New York, pp 81–97

Tuvblad C, Grann M, Lichtenstein P (2006) Heritability for adolescent antisocial behavior differs with socioeconomic status: gene–environment interaction. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:734–743

Van der Sluis S, Dolan CV, Neale MC, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D (2006) Detecting genotype–environment interaction in monozygotic twin data: comparing the Jinks and Fulker test and a new test based on marginal maximum likelihood estimation. Twin Res Hum Genet 9(3):377–392

van der Sluis S, Posthuma D, Dolan CV (2011) A note on false positives and power in G × E modelling of twin data. Behav Genet. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9480-3

Van der Sluis S, Willemsen G, de Geus EJC, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D (2008) Gene–environment interaction in adults’ IQ scores: measures of past and present environment. Behav Genet 38:372–389

Wallace GL, Schmitt JE, Lenroot R, Viding E, Ordaz S, Rosenthal MA et al (2006) A pediatric study of twin brain morphology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:987–993

Zhang Z, Ilies R, Arvey RD (2009) Beyond genetic explanations for leadership: the moderating role of the social environment. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 110:118–128

Acknowledgments

The research by Dylan Molenaar was made possible by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). Sophie van der Sluis is financially supported by research grants NWO/MaGW VENI-451-08-025 and VIDI-016-065-318. All Mx syntax files of the models described in this paper are available from the site of the first author, www.dylanmolenaar.nl. We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers whose comments led to substantial improvements of this paper.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by Stacey Cherny.

Appendix

Appendix

Distinction between C × E and A × E within an ACE–A × E–C × E model

In this appendix we show that within an ACE–A × E–C × E model the A × E and C × E effects are empirically unidentified. The results below are obtained under circumstances similar to scenario I from the paper. Table 9 depicts the power of an ACE–A × E–C × E model to detect C × E and A × E.

The Table 9 shows that when an A × E is in the data, the effect is not detected as A × E and not as C × E within the ACE–A × E–C × E model. This is because the A × E effect can arise as both C × E and as A × E in the model. Thus, consider the case that A × E is in the data, and the ACE–A × E–C × E is fitted. Dropping the A × E effect from the model shows no deterioration in model fit (while the A × E effect is in the data) as the A × E effect is fully absorbed in the C × E parameter. When the A × E parameter is freed, and the C × E parameter is dropped, model fit again shows no deterioration as the A × E effect is now be absorbed by the A × E parameter. Same holds for the case when a C × E effect is in the data.

When the ACE–A × E and the ACE–C × E models are considered, power is always large irrespective of the exact effect that is in the data. For instance, power of ACE–A × E is large when an A × E is in the data and when an A × C is in the data. From the above we conclude that the A × E parameter can not be distinguished from the C × E parameter (the parameters are highly correlated) under reasonable circumstances (i.e. the chosen effect and sample sizes).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Molenaar, D., van der Sluis, S., Boomsma, D.I. et al. Detecting Specific Genotype by Environment Interactions Using Marginal Maximum Likelihood Estimation in the Classical Twin Design. Behav Genet 42, 483–499 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-011-9522-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-011-9522-x