Abstract

Management scholars in the West engage in a variety of work that tends to divide between scholarly research and practical endeavors. The schism has not historically existed in China and the East, where scholarship and practice are by tradition regarded as an integrated whole. This paper seeks to narrow the gulf by exploring the conception of management scholarship in the global context, a concern that goes to the heart of what an academic career in management means today, and how scholars may contribute to research and the profession in general. This paper conveys lessons and insights from my three decades of scholarly work developing competitive dynamics and ambicultural management as distinctive research domains, as well as academic and business ventures I have founded to support my research. All these entrepreneurial undertakings are grounded in an expansive, integrated “Chinese” view of management scholarship. Academics seeking to explore synergies between scholarship and practice and to achieve a balanced career anchored in research may find that my entrepreneurial efforts to integrate scholarly and practical ventures offer a useful guide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For our purpose, practice comprises teaching, professional service, and work in the corporate and public arenas.

The first-person narrative format will be used in the remainder of the paper, in light of its personal nature.

It should be noted that the “publish or perish” problem is a relatively modern phenomenon that may be said to have originated with the 1959 Ford Foundation report “Higher Education for Business” by the economists Robert Aaron Gordon and James Edwin Howell. At the time, American business schools were often regarded as “trade schools” where students could attain functional skills like bookkeeping. As Gordon and Howell (1959) wrote, “The vocational approach that has all too often characterized [schools of business administration] in the past is now considered inadequate.” The shift to a research orientation, the report said, would be necessary for business schools to meet the test of “advancing the state of knowledge” rather than merely “transmitting present knowledge.” Looking back still another half century, the beginning of management research may be traced to Frederick Taylor’s studies of workforce productivity and economic efficiency in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, suggesting that research and practice were once more integrated in the US than they are today.

For example, more than a million copies of case studies written by a well-regarded business faculty member have been sold. Likewise, textbook writing and publication can also be financially rewarding.

A special conference on competitive dynamics was held in 2018 at Queen’s University, in Ontario, Canada, on the 30th anniversary of the publication of my dissertation. The meeting was organized by a group of prominent strategy scholars who consider the paper to be a cornerstone of the field of competitive dynamics.

The publications included two each in Administrative Science Quarterly (e.g., Hambrick et al., 1996), Academy of Management Review (e.g., Chen, 1996, which received best paper recognition), and Strategic Management Journal (e.g., Chen & Miller, 1994); four in Academy of Management Journal (e.g., Chen & MacMillan, 1992); and one each in Management Science (Chen, Smith, & Grimm, 1992) and Social Forces (Miller & Chen, 1996).

At the June 2018 CDIC, I identified, in addition to “MJC and his ‘Outside Intruders,’” three other major forces that helped form the research subfield in strategic management: “The Smith-Grimm Dynamic Duo and Their Maryland Gang” (e.g., Ferrier, Smith, & Grimm, 1999; Smith, Grimm, & Gannon, 1992), “The Multipoint, Multimarket Attackers” (e.g., Baum & Korn, 1996; Gimeno & Woo, 1996), and “The Hyper D’Aveni” (e.g., D’Aveni, 1994).

I was humbled to see in the findings of a new study (Aguinis et al., in press) that my research placed me among the top 100 most influential strategy authors (out of a total of more than 6,000) for scholarly impact on strategy textbooks, and I was edified by the implications for my quest for scholarship-practice integration.

Demonstrating the “indirect competition” perspective (McGrath, Chen, & MacMillan, 1998), I had not paired the words “competitive” and “dynamics” until Baum and Korn’s (1996) landmark work, instead interchangeably using “interaction,” “rivalry,” “engagement,” or “interfirm competition.” The decision to not adopt the term “competitive dynamics” was strategic and may be attributed in part to the deep-rooted conception in economics that the term “dynamics” is associated with temporal factors, a notion that prevailed during the early days of the strategy field.

Corporate consulting clients have included Rolls Royce, Munich Re, Morgan Stanley, Merck, United Technology, Taiwan Mobile, Ford-Taiwan, Tsinghua Holdings, and Tencent. Business symposia I have addressed include the World Economic Forum–China, PBS Presidential Forum (with panelists including Tim Kaine, later the 2016 Democratic US Vice Presidential candidate), and HSM-hosted programs in Milan and Sao Paolo (with speakers like Jack Welch and Japanese management guru Kenichi Ohame). Given my scholarship-centric orientation, I found myself being strategic in deciding when to engage in non-academic or business programs, as they can distract from the scholarly core and focus.

The 2007 conferences were a model demonstration of the idea of competitive asymmetry (Chen, 1996), whereby two organizations or entities regard their competitive relationship differently. Seeing, in short order, Western and Chinese business leaders’ diametrically opposed viewpoints provided me with a rich opportunity for ambicultural learning. I challenged my Western audience to consider factors ABC in their consideration of the “China threat,” while I suggested that my Chinese audience reflect on issues XYZ before they reached their conclusion that Western multinationals were bent on “colonizing” China.

During my four-year tenure in this role, GCBI offered new courses for MBAs and undergraduate students, funded and sponsored visiting scholars, hosted an East-West.com conference and speaker series (inviting for instance, Jack Ma of Alibaba during its founding years, at that time a fledgling firm with 43 employees), and collaborated with academic programs such as China’s National MBA Advisory Board and the Chinese University of Hong Kong. I also published Inside Chinese Business: A Guide to Managers Worldwide (Harvard Business Press, 2001). All these activities were supported by a group of about 30 dedicated Wharton undergraduates, volunteers referred to by associates as “toy soldiers,” all of whom shared my ideal of “making the world smaller.”

The definition of “research” is a somewhat contextual issue. Different schools have their own notion of what research comprises. In my early days at Columbia, for example, only articles published in four “A-list” journals were considered to be research. This paper takes a more balanced consideration, regarding any refereed publications as research. I want to emphasize the point that publishing immediately in top-tier journals may be difficult for certain types of research, and that it is acceptable, and sometimes advisable, to proceed in a stepwise fashion from publication in less prestigious publications to the top journals. At some institutions, research may include case writing and writing for practical business audiences (considered here as part of practical venturing).

Many accomplished and retired business executives and entrepreneurs around the world have joined doctoral programs in business administration and/or PhD programs in practice. Some have found that what made them successful in business presents significant barriers for future success in the academic world. Finding the ambicultural balance between the different professions and careers, though a potential challenge, is in its own right an opportunity for rewarding learning.

The integrative mindset that spans scholarly and practical entrepreneurial venturing is exemplified in a remark by David Ho: “I may be a wise scholar, a famous businessman or a good father and husband, but until I am all, I have not succeeded” (Chen, 2001: 90).

This is a sample of questions I have regularly fielded throughout my academic career as recounted in a recent case, “Why Should I Care?” (UVA-S-301), which I use as a wrap-up in my research-based MBA elective course in competitive dynamics.

As I was finishing this paper, I was deeply saddened to receive news of the death of Jim Fredrickson. During the short period we overlapped at Columbia, Jim’s coaching in how to deal with reviewers and handle the revision process was instrumental in shaping me as a scholar and researcher. In addition to his seminal scholarly contributions to the study of strategic decision-making, Jim had a long, outstanding tenure on the faculty at University of Texas at Austin as head of the management department.

References

Aguinis, H., Ramani, R. S., Alabduljader, N., Bailey, J. R., & Lee, J. in press. A pluralist conceptualization of scholarly impact in management education: Students as stakeholders. Academy of Management Learning and Education. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2017.0488.

Arndt, F. F., & Ashkanasy, N. 2015. Integrating ambiculturalism and fusion theory: A world with open doors. Academy of Management Review, 40(1): 144–147.

Bansal, P., Bertels, S., Ewart, T., MacConnachie, P., & O’Brien, J. 2012. Bridging the research–practice gap. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(1): 73–92.

Bansal, P., Smith, W., & Vaara, E. 2018. From the editors: New ways of seeing through qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 61(4): 1189–1195.

Baron, R., Hmieleski, K., & Henry, R. 2012. Entrepreneurs’ dispositional positive affect: The potential benefits—and potential costs—of being “up”. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(3): 310–324.

Bartunek, J. M., & Rynes, S. L. 2014. Academics and practitioners are alike and unlike: The paradoxes of academic practitioner relationships. Journal of Management, 40(5): 1181–1201.

Baum, J. A., & Korn, H. J. 1996. Competitive dynamics of interfirm rivalry. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2): 255–255.

Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. 1995. Disruptive technologies: Catching the wave. Harvard Business Review, 73(1): 43–53.

Chen, M.-J. 1988. Competitive strategic interaction: A study of competitive actions and responses. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park.

Chen, M.-J. 1996. Competitor analysis and interfirm rivalry: Toward a theoretical integration. Academy of Management Review, 21(1): 100–134.

Chen, M.-J. 2001. Inside Chinese business: A guide for managers worldwide. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Chen, M.-J. 2008. Reconceptualizing the competition-cooperation relationship: A transparadox perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry, 17(4): 288–304.

Chen, M.-J. 2009. Competitive dynamics research: An insider’s odyssey. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(1): 5–26.

Chen, M.-J. 2010. Reflecting on the process: Building competitive dynamics research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 27(1): 9–24.

Chen, M.-J. 2014. Becoming ambicultural: A personal quest, and aspiration for organizations. Academy of Management Review, 39(2): 119–137.

Chen, M.-J. 2016. Competitive dynamics: Eastern roots, Western growth. Cross Cultural and Strategic Management, 23(4): 510–530.

Chen, M.-J. 2018. The research-teaching “oneness” of competitive dynamics: Toward an ambicultural integration. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(2): 1–27.

Chen, M.-J., & MacMillan, I. C. 1992. Nonresponse and delayed response to competitive moves: The roles of competitor dependence and action irreversibility. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3): 359–370.

Chen, M.-J., & Miller, D. 1994. Competitive attack, retaliation and performance: An expectancy-valence framework. Strategic Management Journal, 15(2): 85–102.

Chen, M.-J., & Miller, D. 2010. West meets East: Towards an ambicultural approach to management. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(4): 17–24.Chen, M.-J., & Miller, D. 2011. The relational perspective as a business mindset: Managerial implications for East and West. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(3): 6–18.

Chen, M.-J., & Miller, D. 2012. Competitive dynamics: Themes, trends, and a prospective research platform. Academy of Management Annals, 6(1): 135–210.

Chen, M.-J., & Miller, D. 2015. Reconceptualizing competitive dynamics: A multidimensional framework. Strategic Management Journal, 36(5): 758–775.

Chen, M.-J., Smith, K. G., & Grimm, C. 1992. Action characteristics as predictors of competitive response. Management Science, 38(3): 439–455.

Child, J. 1972. Organizational structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice. Sociology, 6(1): 1–22.

D’Aveni, R. A. 1994. Hypercompetition: Managing the dynamics of strategic maneuvering. New York: Free Press.

Davis, G. F., & Thompson, T. A. 1994. A social movement perspective on corporate control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(1): 141–173.

Dees, J. G. 2001. The meaning of social entrepreneurship. Stanford: Stanford Graduate Business School.

DiMaggio, P. J. 1988. Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. Zucker (Ed.). Institutional patterns and organizations: 3–22. Cambridge: Ballinger.

Economist. 2018. How global university rankings are changing higher education. https://www.economist.com/international/2018/05/19/how-global-university-rankings-are-changing-higher-education. Accessed May 19, 2018.

Ferrier, W. J., Smith, K. G., & Grimm, C. M. 1999. The role of competitive action in market share erosion and industry dethronement: A study of industry leaders and challengers. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4): 372–388.

Gimeno, J., & Woo, C. 1996. Hypercompetition in a multimarket environment: The role of strategic similarity and multimarket contact in competitive de-escalation. Organization Science, 7(3): 322–340.

Gordon, R. A., & Howell, J. E. 1959. Higher education for business. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hambrick, D. C., & Chen, M.-J. 2008. New academic fields as admittance-seeking social movements: The case of strategic management. Academy of Management Review, 33(1): 32–54.

Hambrick, D. C., Cho, T. S., & Chen, M.-J. 1996. The influence of top management team heterogeneity on firms’ competitive moves. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4): 659–684.

Hofer, C. W., & Schendel, D. E. 1978. Strategy formulation: Analytical concepts. St. Paul: West Educational.

Lee, T. W. 2009. The management professor. Academy of Management Review, 34(2): 196–199.

Leung, K. 2012. Indigenous Chinese management research: Like it or not, we need it. Management and Organization Review, 8(1): 1–5.

Lewin, K. 1946. Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4): 34–46.

Li, P., Leung, K., Chen, C., & Luo, J. 2012. Indigenous research on Chinese management: What and how. Management and Organization Review, 8(1): 7–24.

MacMillan, I. C., McCaffery, M. L., & Van Wijk, G. 1985. Competitor’s responses to easily imitated new products: Exploring commercial banking product introductions. Strategic Management Journal, 6(1): 75–86.

McGrath, R. G., Chen, M.-J., & MacMillan, I. C. 1998. Multimarket maneuvering in uncertain spheres of influence: Resource diversion strategies. Academy of Management Review, 23(4): 724–740.

Michaelson, C. 2015. How reading novels can help management scholars cultivate ambiculturalism. Academy of Management Review, 40(1): 147–149.

Miller, D. 2014. A downside to the entrepreneurial personality?. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 39(1): 1–8.

Miller, D., & Chen, M.-J. 1994. Sources and consequences of competitive inertia: A study of the US airline industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(1): 1–23.

Miller, D., & Chen, M.-J. 1996. Nonconformity in competitive repertoires: A sociological view of markets. Social Forces, 74(4): 1209–1234.

Miller, D., & Miller, I. 2018. Publishing and its discontents: A path-goal expectancy view of alienation among management scholars. Working paper.

Miller, D., & Sardais, C. 2015. Bifurcating time: How entrepreneurs reconcile the paradoxical demands of the job. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 39(3): 489–512.

Mintzberg, H. 2004. Managers not MBAs: A hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Molinsky, A. 2007. Cross-cultural code switching: The psychological challenges of adapting behavior in foreign cultural interactions. Academy of Management Review, 32(2): 622–640.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. 2002. The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1(1): 78–95.

Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive strategy techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

Schuster, J. H., & Finkelstein, M. J. 2006. American faculty: The restructuring of academic work and careers. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. 2000. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1): 217–226.

Siegel, D., & Wright, M. 2015. Academic entrepreneurship: Time for a rethink?. British Journal of Management, 26(4): 582–595.

Silva, M. D. 2015. Academic entrepreneurship and traditional academic duties: Synergy or rivalry?. Studies in Higher Education, 41(12): 2169–2183.

Smith, K. G., Ferrier, W. J., & Ndofor, H. 2001. Competitive dynamics research: Critique and future directions. In M. Hitt, R. E. Freeman, & J. Harrison (Eds.). Handbook of strategic management: 315–361. London: Blackwell.

Smith, K. G., Grimm, C. M., & Gannon, M. J. 1992. Dynamics of competitive strategy. Newsbury Park: Sage.

Smith, S., Warda, V., & House, A. 2011. Impact in the proposals for the UK’s research excellence framework: Shifting the boundaries of academic autonomy. Research Policy, 40(10): 1369–1379.

Toole, A. A., & Czarnitzki, D. 2009. Exploring the relationship between scientist human capital and firm performance: The case of biomedical academic entrepreneurs in the SBIR program. Management Science, 55(1): 101–114.

Tsai, W., Su, K., & Chen, M.-J. 2011. Seeing through the eyes of a rival: Competitor acumen based on rival-centric perceptions. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4): 761–778.

Tsui, A. S. 2013. The spirit of science and socially responsible scholarship. Management and Organization Review, 9(3): 375–394.

Van de Ven, A. H. 2007. Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vermeulen, F. 2005. On rigor and relevance: Fostering dialectic progress in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6): 978–982.

Wiarda, H. J. 2013. Culture and foreign policy : The neglected factor in international relations. Farnham: Ashgate.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to Ian C. MacMillan, mentor, co-author, and inspiring role model of an academic entrepreneur. Dr. MacMillan’s enlightening counsel and support led me to found my first entrepreneurial venture, the Global Chinese Business Initiative, at Wharton (1997–2001). I would also like to thank Theresa Cho, Dan Li, John Michel, Danny Miller, and Wenpin Tsai for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this paper, and Wan-Chien Lien and Dalong Pang for their dedicated assistance in the preparation of this work. My special thanks to Charles Tucker for his thoughtful editorial assistance. Financial support from the Darden Foundation of the University of Virginia is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

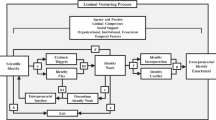

Appendix: Entrepreneurial academic and educational endeavors*

Appendix: Entrepreneurial academic and educational endeavors*

-

1.

Global Chinese Business Initiative at Wharton (GCBI) (1997–2001)

The Global Chinese Business Initiative was founded in 1997 to promote understanding between Western and Chinese enterprises and business and academic professionals. GCBI offers executives unique opportunities for learning and collaboration, fostering awareness of Chinese business thoughts, practices, and networks throughout mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, the Asia-Pacific region, and around the world. My work during this time laid the foundation for all the major organizational venturing activities (most of which are discussed in this paper) I have undertaken over the past two decades.

-

2.

Competitive Dynamics International Conference (CDIC)

To support my core competitive dynamics research and its business application, Chinese scholars led by Professor Hao-Chieh Lin (Taiwan’s Sun-Yet Sen University) took the initiative to start this annual conference in 2010. CDIC has been co-sponsored by leading Chinese universities including Cheng Kung (2010) and Chengchi (2011 and 2014) in Taiwan and Fudan (2012), Tsinghua-SEM (School of Economics and Management) (2013), and Peking-Guanghua (2015) in mainland China. Since 2016, CDIC has been organized by Chinese executives and EMBAs/DBAs I have taught. Each annual conference has attracted 200 or so business academics and executives to discuss cutting-edge strategy and competition issues.

-

3.

Chinese Management Scholars Community (CMSC)

Founded in 2006 at Georgia State University as a small “workshop” for Chinese-speaking scholars in strategic management (a total of 21 assistant professors and doctoral students) attending Academy of Management’s annual conference meeting, CMSC is grass-roots, voluntary effort guided by the mission “to pass the baton” (傳承). CMSC has grown into a community of more than 500 active members unified by a goal of developing research-centered, balanced business academics. CMSC’s core values derive from the “middle” or “zhong” (中) philosophy: integrity, harmony, balance, integration, and independence. Each year it offers a slate of programs, including reunion, research, and teaching forums and workshops and a mentors camp during and after the Academy national meeting. CMSC provides a workable template for professionals outside the mainstream (e.g., newcomers to the association) who can find a “home” in the bigger community and make contributions. Any group of “minority” professionals, not just Chinese, can replicate this approach (Chen, 2014).

-

4.

Chinese Management Scholars Workshop (CMSW)

CMSW, similar to CMSC, is a grassroots organization that a few Chinese colleagues helped me found in 2013. Its roots go back to a two-week workshop I taught in 1997 at Tsinghua University. The first workshop was hosted by the MBA Advisory Board of China’s Ministry of Education for a group of Chinese organizations and management professors who had taught the first cohort of 54 MBAs in China. Some of these scholars (all of whom are now well-established academicians) reunited at Tsinghua University in 2013. To “pass the baton,” we formed a scholarly community for academics in mainland China. Since then, we have partnered with various institutions and held a two-day annual meeting for the past several years: Huazhong University of Science & Technology (2014), Nankai University (2015), Zhejiang University of Science and Technology and Zhejiang University (2016), and Jilin University (2017).

The mission of CMSW is to develop well-rounded academics who can meet China’s unique institutional, intellectual, and educational needs. Unlike most research-centric conferences, CMSW offers a wide range of topics at its annual meeting, addressing pertinent issues that span teaching, research, administration, and business practice. There is a strong need for this kind of broad-based career development of Chinese scholars, and future conference hosts have been lined up through 2022. Each year, CMSC attracts 150 to 200 participants.

-

5.

Visiting Scholars

To help enhance East-West academic exchanges and provide opportunities for Chinese and/or European scholars to gain exposure to the research and teaching environments beyond their home countries, I have been inviting promising young scholars to spend a year with me in the US as a visiting scholar. (Most are self-funded; I help find support for those who are not. To date, I have engaged a total of 23 visiting scholars). I have always found these experiences gratifying. As one example, one such visiting scholar was a doctoral student during her visit in 1998; she is now a well-established full professor in Hong Kong who serves as associate editor of a leading management journal.

-

6.

Wangdao Management Program

Wangdao (王道), or “the royal way,” has been a key tenet of Chinese thought for thousands of years (Chen, Peking University Press, 2011). Today it is a mode of thought urgently needed by global corporate leaders. Pursuing mutual success, wangdao businesses are ambitious but do not seek to control everything; though they avoid confrontation, they are able to maintain competitive advantage and achieve great success. In contrast, businesses of ba dao (霸道), or “the overbearing way,” consider only their own interests. They stick to the zero-sum and winner-take-all competition model and the law of the jungle (“eat or be eaten”). They might be big, but they are not sustainable. Based on the wangdao ideal (Menzi), in 2011 I cofounded with Stan Shih, legendary founder of Taiwan’s Acer Co., an elite executive development program that aims to shape business leaders who are amenable to applying this ancient Chinese philosophy within their enterprises.

-

7.

Xiashang Global Business Program

The Xiashang Global Leadership Management Program, founded in 2013, is based on Xiaxue (夏學), or a “pure wisdom crystallization” of Chinese culture, regarded as the source of Confucianism. (Xia, it should be noted, does not refer to the Xia Dynasty but rather to “Chinese people; great people.”) Xiaxue can integrate a hundred schools of thought and relates to Huaxia (華夏), a concept that combines enlightenment and “greatness,” meaning the fulfillment of human potential, for the benefit of humanity. Hua (華) means light; that is, using light to disperse darkness, to bring enlightenment to everyone and everything in the world. The Xiashang (夏商) Global Leadership Management comprises a group of entrepreneurs who uphold the inclusiveness and openness of the Huaxia spirit to create endeavors for the general welfare of all mankind. Based on the essence of Xiaxue, the program aims to promote the new management thinking of ambiculturalism and to manifest the spirit and model of global entrepreneurs as represented by Huaxia culture.

-

8.

The Oneness Academy

The Academy was founded in 2016 by a group of students as a platform for former students to study and practice together. Any of my students, past and present, and their family members, are welcome to join. The Academy originates from the concepts of JingYi (精一) and ambiculturalism and has its roots in the teachings of Master Yu (e.g., “Use the wisdom of our ancients to inspire our own wisdom”) and Confucius (e.g., “Everyone can be Yao (堯) and Shun (舜),” the two most inspiring leaders or emperors in ancient China. We always refer to scholars as the representative of Zhi (知) or knowledge, and to entrepreneurs as the representative of Xing (行) or practice. The Oneness Academy helps students to integrate knowledge and practice and discover their own “One” to pursue throughout their life.

*These entrepreneurial ventures are listed according to the order of their appearance in Exhibit 1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, MJ. Scholarship-practice “oneness” of an academic career: The entrepreneurial pursuit of an expansive view of management scholarship. Asia Pac J Manag 35, 859–886 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9625-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9625-5