Abstract

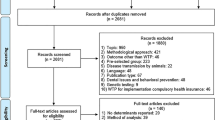

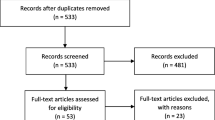

Stated preference (SP) methods are increasingly being applied to HIV-related research and continuously provide researchers with health utility scores of select healthcare products or services that populations consider important. Following PRISMA guidelines, we sought to understand how SP methods have been applied in HIV-related research. We conducted a systematic review to identify studies meeting the following criteria: SP method is clearly stated, conducted in the United States, was published between 01/01/2012 and 02/12/2022, and included adults aged 18 and over. Study design and SP method application were also examined. We identified six SP methods (e.g., Conjoint Analysis, Discrete Choice Experiment) across 18 studies, which were categorized into one of two groups: HIV prevention and HIV treatment-care. Categories of attributes used in SP methods largely focused on: administration, physical/health effects, financial, location, access, and external influences. SP methods are innovative tools capable of informing researchers on what populations consider most beneficial when deciding on treatment, care, or prevention options for HIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Made available upon request. Requests should be emailed to crodr738@fiu.edu.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Kroes EP, Sheldon RJ. Stated preference methods: an introduction. JTEP. 1988;22(1):11–25.

Raghavarao D, Wiley JB, Chitturi P. Choice-based conjoint analysis: models and designs. 1st ed. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2010.

Ryan M, Hughes J. Using conjoint analysis to assess women’s preferences for miscarriage management. Health Econ. 1997;6(3):261–73.

O’Connell S, Queally M, Savage E, Murphy DM, Mc Carthy VJC. Preferences for support in managing symptoms of an asthma flare-up: a pilot study of a discrete choice experiment. J Asthma. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2022.2054429.

Simblett S, Pennington M, Quaife M, Theochari E, Burke P, Brichetto G, et al. Key drivers and facilitators of the choice to use mHealth technology in people with neurological conditions: observational study. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(5): e29509.

Zhang M, He X, Wu J, Wang X, Jiang Q, Xie F. How do treatment preferences of patients with cancer compare with those of oncologists and family members? Evidence from a discrete choice experiment in China. Value in Health. 2022;25(10):1768–77.

Fifer S, Ordman R, Briggs L, Cowley A. Patient and clinician preferences for genetic and genomic testing in non-small cell lung cancer: a discrete choice experiment. J Pers Med. 2022;12(6):879–98.

Yan J, Wei Y, Teng Y, Liu S, Li F, Bao S, et al. physician preferences and shared-decision making for the traditional chinese medicine treatment of lung cancer: a discrete-choice experiment study in China. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:1487–97.

Graf MA, Tanner DD, Swinyard WR. Optimizing the delivery of patient and physician satisfaction: a conjoint analysis approach. Health Care Manage Rev. 1993;18(4):34–43.

Ostermann J, Njau B, Hobbie A, Mtuy T, Masaki ML, Shayo A, et al. Using discrete choice experiments to design interventions for heterogeneous preferences: protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of a preference-informed, heterogeneity-focused, HIV testing offer for high-risk populations. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11): e039313.

Shrestha R, Alias H, Wong LP, Altice FL, Lim SH. Using individual stated-preferences to optimize HIV self-testing service delivery among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Malaysia: results from a conjoint-based analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09832-w.

Galárraga O, Kuo C, Mtukushe B, Maughan-Brown B, Harrison A, Hoare J. iSAY (incentives for South African Youth): stated preferences of young people living with HIV. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265: 113333.

Soekhai V, Whichello C, Levitan B, Veldwijk J, Pinto CA, Donkers B, et al. Methods for exploring and eliciting patient preferences in the medical product lifecycle: a literature review. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(7):1324–31.

Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Carson RT. Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. J Choice Model. 2010;3(3):57–72.

Jervis SM, Ennis JM, Drake MA. A comparison of adaptive choice-based conjoint and choice-based conjoint to determine key choice attributes of sour cream with limited sample size. J Sens Stud. 2012;27(6):451–62.

Sawtooth Software. What is the Difference Between ACA and CBC? 2019. https://sawtoothsoftware.com/resources/knowledge-base/sales-questions/what-is-the-difference-between-aca-and-cbc.

Ali S, Ronaldson S. Ordinal preference elicitation methods in health economics and health services research: using discrete choice experiments and ranking methods. Br Med Bull. 2012;103(1):21–44.

Tran BX, Nguyen LH, Ohinmaa A, Maher RM, Nong VM, Latkin CA. Longitudinal and cross sectional assessments of health utility in adults with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:7.

Beckham SW, Crossnohere NL, Gross M, Bridges JFP. Eliciting preferences for HIV prevention technologies: a systematic review. Patient. 2021;14(2):151–74.

Eshun-Wilson I, Kim HY, Schwartz S, Conte M, Glidden DV, Geng EH. Exploring relative preferences for HIV service features using discrete choice experiments: a synthetic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17(5):467–77.

Humphrey JM, Naanyu V, MacDonald KR, Wools-Kaloustian K, Zimet GD. Stated-preference research in HIV: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10): e0224566.

McGrady ME, Pai ALH, Prosser LA. Using discrete choice experiments to develop and deliver patient-centered psychological interventions: a systematic review. Health psychol. 2021;15(2):314–32.

Sharma M, Ong JJ, Celum C, Terris-Prestholt F. Heterogeneity in individual preferences for HIV testing: a systematic literature review of discrete choice experiments. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30: 100653.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89.

Conte M, Eshun-Wilson I, Geng E, Imbert E, Hickey MD, Havlir D, et al. Brief Report: Understanding preferences for HIV care among patients experiencing homelessness or unstable housing: a discrete choice experiment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(4):444–9.

Ostermann J, Mühlbacher A, Brown DS, Regier DA, Hobbie A, Weinhold A, et al. Heterogeneous patient preferences for modern antiretroviral therapy: results of a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2020;23(7):851–61.

Lyons A, Bilker WB, Hines J, Gross R. Effect of format on comprehension of adherence data in chronic disease: a cross-sectional study in HIV. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(1):154–9.

Yelverton V, Ostermann J, Hobbie A, Madut D, Thielman N. A mixed methods approach to understanding antiretroviral treatment preferences: what do patients really want? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(9):340–8.

Shumway M, Luetkemeyer AF, Peters MG, Johnson MO, Napoles TM, Riley ED. Direct-acting antiviral treatment for HIV/HCV patients in safety net settings: patient and provider preferences. AIDS Care. 2019;31(11):1340–7.

Jones DL, Cook R, Potter JE, Miron-Shatz T, Chakhtoura N, Spence A, et al. Fertility desires among women living with HIV. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9): e0160190.

Simoni JM, Tapia K, Lee SJ, Graham SM, Beima-Sofie K, Mohamed ZH, et al. A conjoint analysis of the acceptability of targeted long-acting injectable antiretroviral therapy among persons living with HIV in the U.S. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(4):1226–36.

Lee S-J, Brooks R, Bolan RK, Flynn R. Assessing willingness to test for HIV among men who have sex with men using conjoint analysis, evidence for uptake of the FDA-approved at-home HIV test. AIDS Care. 2013;25(12):1592–8.

Lee SJ, Newman PA, Comulada WS, Cunningham WE, Duan N. Use of conjoint analysis to assess HIV vaccine acceptability: feasibility of an innovation in the assessment of consumer health-care preferences. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(4):235–41.

Primrose RJ, Zaveri T, Bakke AJ, Ziegler GR, Moskowitz HR, Hayes JE. Drivers of vaginal drug delivery system acceptability from internet-based conjoint analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3): e0150896.

Schieffer RJ, Bryndza Tfaily E, D’Aquila R, Greene GJ, Carballo-Diéguez A, Giguere R, et al. Conjoint analysis of user acceptability of sustained long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021;38(4):336–45.

Shrestha R, Karki P, Altice FL, Dubov O, Fraenkel L, Huedo-Medina T, et al. Measuring acceptability and preferences for implementation of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) using conjoint analysis: an application to primary HIV prevention among high risk drug users. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1228–38.

Sharma A, Stephenson RB, White D, Sullivan PS. Acceptability and intended usage preferences for six HIV testing options among internet-using men who have sex with men. Springerplus. 2014;3:109.

Zaveri T, Primrose RJ, Surapaneni L, Ziegler GR, Hayes JE. Firmness perception influences women’s preferences for vaginal suppositories. Pharmaceutics. 2014;6(3):512–29.

Asiago-Reddy EA, McPeak J, Scarpa R, Braksmajer A, Ruszkowski N, McMahon J, et al. Perceived access to PrEP as a critical step in engagement: a qualitative analysis and discrete choice experiment among young men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1): e0258530.

Dubov A, Ogunbajo A, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. Optimizing access to Prep based on MSM preferences: results of a discrete choice experiment. AIDS Care. 2019;31(5):545–53.

Gutierrez JI, Dubov A, Altice FL, Vlahov D. Preferences for pre-exposure prophylaxis among U.S. military men who have sex with men: results of an adaptive choice based conjoint analysis study. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):32.

Van Gerwen OT, Talluri R, Camino AFMS, Mena LA, Chamberlain N, Ford EW, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted infection testing preferences for young black men who have sex with men in the Southeastern United States: implications for a post-COVID-19 era. Sex Transm Dis. 2022;49(3):208–15.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. What is the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. Initiative? 2021 https://ahead.hiv.gov/about-ehe.

Orme BK. Sample size issues for conjoint analysis. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. 4th ed. Madison, Wis.: Research Publishers LLC; 2019.

Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Halversen C. Sawtooth Software, editor2020 December 29, 2020. https://sawtoothsoftware.com/resources/blog/posts/sample-size-rules-of-thumb.

Sawtooth Software. Discover. Provo, UT 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2020 updated May 2022. Vol. 33. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and Transgender People: Prevention Challenges 2022 [cited 2022 July 17]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/prevention-challenges.html.

Reisner SL, Jadwin-Cakmak L, White Hughto JM, Martinez M, Salomon L, Harper GW. Characterizing the HIV prevention and care continua in a sample of transgender youth in the U.S. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(12):3312–27.

Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. London: Sage publications; 2017.

Funding

This work was supported by the Veteran’s Fellowship provided by the Graduate School at Florida International University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

See data extraction paragraph in Methods. CR lead manuscript development, including table creation, and wrote the first draft. JM edited and finalized the writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial, non-financial, or competing interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodriguez, C.A., Mitchell, J.W. Use of Stated Preference Methods in HIV Treatment and Prevention Research in the United States: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav 27, 2328–2359 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03962-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03962-5