Abstract

People with HIV (PWH) smoke at higher rates compared with the general population and have lower cessation rates. The primary aim of this study was to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on smoking in PWH. A survey was administered to participants in two smoking cessation trials in the United States. Mean cigarettes per day was 13.9 (SD 8.6), and participants reported they had smoked on average for 30.93 years (SD 10.4). More than half (55.7%) of participants (N = 140) reported not changing their smoking during the pandemic, while 15% reported decreasing, and 25% reported increasing their smoking. In bivariate analyses, worrying about food due to lack of money (χ2 = 9.13, df 2, p = 0.01) and greater Covid-related worry (rs = 0.19, p = 0.02) were significantly associated with increased smoking. Qualitative research may be needed to more clearly elucidate factors related to smoking behaviors among PWH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic affected nearly every aspect of daily life in the United States for most people. In mid-March of 2020, restrictions were put in place in most states across the United States (U.S.) and social distancing became the norm. This mandate resulted in reduced social interaction and increased social isolation among many groups. Psychological distress, including loneliness, related to the pandemic has been reported [1], and the effect was more pronounced among those with lower socioeconomic status. This change in levels of social interaction and the resultant psychological effects has led to increased daily stress for many, including people with HIV (PWH), and may have exacerbated behaviors that many people report using to manage stress [2, 3], namely cigarette smoking. For the first time in 20 years, the Federal Trade Commission reported that cigarette sales increased during 2020, further demonstrating the pandemic’s effect on smoking behaviors [4].

Irrespective of COVID-19, smoking prevalence is higher in PWH compared with the general population [5] and this group of smokers generally smokes more heavily and reports higher levels of nicotine dependence [6]. PWH who smoke often report high rates of comorbid anxiety and stress, both factors that have been related to poor smoking cessation outcomes [2, 7]. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, studies among PWH have repeatedly found that a significant majority of smokers’ report that symptoms of anxiety and depression were barriers to making a quit attempt and maintaining abstinence following a quit attempt [8, 9]. Further, PWH endorse that smoking is a key strategy to help them manage or alleviate the daily stress associated with living with HIV [2, 10, 11]. These key relationships between mood and smoking in PWH might suggest that COVID-19 pandemic-related stress could hinder smoking cessation efforts.

Worry and anxiety among PWH may be further increased by the COVID-19 pandemic due to reports that highlight increased severity of COVID-19 infection in people who smoke [12, 13] and in those with underlying chronic health conditions [14,15,16] (such as HIV). In fact, two recent meta-analyses concluded that HIV increased the risk of death from COVID-19 by 78–95% [16, 17]. One report indicated that among the general population of people who smoke on a nondaily level worry and fear increased from pre versus post the onset of the pandemic. In reflecting back, these general population smokers reported a slight increase in their motivation to quit smoking during the pandemic [18]. Given the greater stressors experienced by PWH, they may have been differentially impacted in their motivation to quit smoking during the pandemic. Understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic may have affected PWH who smoke may provide increased understanding into the challenges and barriers that PWH face when attempting to successfully manage smoking cessation and achieve abstinence. This understanding may also help to inform smoking cessation approaches and strategies among HIV researchers and clinicians.

Early in the pandemic, a group of investigators discussed the effect that the COVID-19 pandemic may have on both smoking behaviors and motivation to quit among PWH who smoke [19]. While motivation to quit might have increased due to health concerns, increased worry and anxiety related to the pandemic may have promoted increased smoking levels. A common survey was administered to participants across projects so that a clearer understanding of the pandemic’s effect on this vulnerable group of smokers could be elucidated [20]. The overall aim of this study was to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on daily cigarette smoking, Covid-related stress and worry, and the associations between Covid-related stress/worry and the level of cigarette smoking in PWH.

Methods

Participants

The two studies included in this analysis were recruiting people with HIV who identified as current daily smokers. The sample described here was enrolled in the two ongoing smoking cessation studies in Rhode Island, Illinois, and Pennsylvania at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S.

Procedures

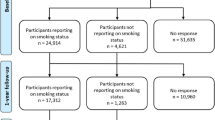

Participants were enrolled in one of two smoking cessation clinical trials: (1) a 24-week randomized trial utilizing peer navigators for social support to quit smoking [21], or (2) a 26-week randomized trial testing the tailoring of a smoking cessation medication to the individual’s nicotine metabolite ratio and/or an adherence intervention to optimize treatment for smoking [22]. Recruitment for both studies was initially started prior to the pandemic (March 2020), halted for 3–4 months, and then resumed in July 2020 with newly added precautions and restrictions. All participants in the present analysis were enrolled between June 2020 and June 2021. Participants were recruited via electronic medical record review by study staff at the academic health systems, or through community recruitment, advertisements on public transportation, television and radio, flyer campaigns, and online advertising through social media.

Prospective participants were screened by phone and, if eligible, were scheduled for an in-person or video visit (based on research restrictions at the time at university settings) to confirm eligibility, complete informed consent, and collect baseline data. Following informed consent, participants who were eligible for the parent study completed the COVID-19 survey as part of their baseline visit. Protocols for the studies included in this analysis have been previously described [21, 22]. Participants were eligible for the studies if they: (1) were diagnosed with HIV; (2) at least 18 years old; (3) smoked daily; and (4) able to use varenicline or nicotine patch safely (one study only). Participants were excluded if they: (1) were already using pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation; (2) had an unstable medical or psychiatric illness; (3) were experiencing symptoms of psychosis; (3) had past-month suicidal ideation or past year suicide attempt; (4) were pregnant; or (5) had a history of epilepsy or seizure disorder (one study only). Participants were compensated for completed study sessions. The respective Institutional Review Boards approved all study procedures.

Measures

Sample demographics were collected via self-report and included age in years, sex at birth (male/female), self-identified gender (female, male, transgender male, transgender female, genderqueer/gender nonconforming), race (White, Black/African American, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, More than One Race, Unknown/not identified), ethnicity (Hispanic/non-Hispanic), education level (years), and employment status (employed, unemployed, retired, disabled, other). We constructed a 47-item COVID-19 survey that included five separate constructs: COVID-19 exposure; life changes due to the COVID-19 crisis and social distancing; COVID-19-related worry; COVID-19-related stress; and COVID-19 impacts on smoking [20]. The survey was completed by the participants on RedCap or Qualtrics (based on site) and took about 20 min to complete.

COVID-19 Exposure (Categorical Variables)

One item asked, “Have you been exposed to someone likely to have COVID-19?” Similarly, a second item asked, “Have you been suspected of having COVID-19?” Response options were yes/no.

Life Changes (Categorical Variables)

Five items asked about life changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic, including: “How has the amount of contact with people outside your home changed? Has the quality of your relationships with your family [friends] changed? Has the COVID-19 crisis created financial problems for you or your family? To what degree are you concerned about the stability of your living situation? Did you worry whether your food would run out because of a lack of money (yes/no)?”

COVID-19-Related Worry (Continuous Variable)

Four items asked “Since the stay-at-home order was issued in March 2020, how worried have you been about (being infected; family and friends being infected; your physical health being influenced by COVID-19; your mental/emotional health being influenced by COVID-19)?” Response options ranged from (0) not all, to (4) extremely. A composite worry score was calculated by adding the response options of the four items together and total worry scores could range from 0 to 16. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91, indicating excellent internal consistency of the scale.

COVID-19-Related Stress (Continuous Variable)

Three items asked about stress related to COVID-19 and stay-at home restrictions: “how stressful have [restrictions on leaving home; changes in family contacts; changes in social contacts (not including family)] been for you?” Response options ranged from (1) not at all, to (5) extremely. A composite stress score was calculated by adding the response options of three items together and could range from 3 to 15. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76, indicating acceptable internal consistency of the scale.

Smoking Status

Smoking was assessed as both a continuous variable and as a categorical variable. Participants were asked (continuous variable): “Prior to the stay-at-home order, how many cigarettes per day were you smoking? How many cigarettes per day are you currently smoking?” Participants were subsequently asked about perceived change in smoking, which was assessed as a categorical variable: “Are you smoking more than, less than, or the same amount as before the pandemic began?”

Cigarette Dependence

The Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) is a validated 6-item scale used to evaluate the severity of cigarette dependence [23]. Scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater dependence.

Data Analysis Plan

All analyses were completed using SPSS (version 25) and SAS (version 9.4). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Paired samples t-tests were used to examine change in cigarettes per day (CPD) prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic (both assessed concurrently at the time of survey administration). ANOVA’s and correlations were used to examine associations between cigarettes per day and categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Chi-square tests and Spearman rank-order correlations were used to examine associations between self-reported change in smoking (less/same/more) and Covid-related variables. CPD and change in smoking (less/same/more) were used as the dependent variables in statistical models. Covid-related variables (i.e., worry, stress) were predictor variables. Variables that with p-values less than 0.10 in bivariate analysis were included in subsequent multivariable analyses. Because no variables were significantly associated with CPD, no multivariable linear regression analysis predicting that outcome was conducted. Multivariable ordered logistic regression was conducted to examine predictors of a change in smoking level (less/same/more) during the pandemic. All statistical tests defined significance by p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 140 surveys were completed and included in the analyses. Demographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1.

Baseline Smoking Characteristics

Mean CPD was 13.9 (SD 8.6), and participants reported they had smoked on average for 30.93 years (SD 10.4). Mean CPD was higher among White smokers (M 16.0, SD 9.02) compared to Black smokers (M 11.6, SD 6.2). Mean age of smoking initiation was 18.4 (SD 6.1) years. Mean FTCD score was 5.1 (SD = 2.3), indicating moderate dependence, and the majority of the sample (n = 122; 87.1%) smoked every day. Participants reported an average of 3.6 (SD 11.8) lifetime quit attempts. Nearly half of the sample (46.4%) reported that they had been told by a physician that they should quit smoking.

Changes in Smoking Behavior Related to Covid Pandemic

During the pandemic, 15% of smokers reported decreasing, 25% of smokers reported increasing, and more than half (55.7%) reported not changing their cigarette consumption. More than two-thirds (69.3%) reported that smoking helped them stay calm during the COVID-19 crisis. More than three-quarters of participants (79.3%) reported that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect their ability to obtain cigarettes (see Table 2). Self-reported smoking (CPD) during the pandemic (M = 13.4; SD = 7.9) was not different compared to self-reported pre-pandemic smoking (M = 13.9; SD = 8.6; t = 1.17; df 131; p = 0.24).

Nearly half of participants (43.6%) reported that the pandemic did not impact their motivation to quit smoking. Nearly half (46.3%) said social support for quitting was impacted by the pandemic, and 40% reported that it was more difficult to make a quit attempt due to the stay-at-home order. Three-quarters of participants (75%) said no new smoking triggers or high-risk situations had emerged during the pandemic, and participants reported they had not changed or adjusted their quit strategies due to the pandemic. Few participants reported making a quit attempt during the pandemic: two participants reported trying to quit with a family member, and another reported trying to eliminate the first cigarette of the day (upon awakening). One participant reported trying to only smoke outside their home as a measure to reduce their smoking.

COVID-19 Exposure/Infection

Fourteen (10%) participants reported being exposed to someone with COVID-19 illness or symptoms, while 7 (5%) participants reported having been diagnosed with COVID-19 illness or symptoms. While only three participants reported having a member of their household test positive for COVID-19, 43 participants (30.7%) reported having a non-household family member or friend test positive for COVID-19. Participants indicated that family members or friends had fallen ill (16.4%), been hospitalized (12.1%), or died (11.4%) due to COVID-19 illness.

Perceived COVID-19-Related Stress/Worry

Participants were asked how worried they were that they would be infected, a family member could be infected, and their physical and/or emotional health would be affected by COVID-19. Results are shown in Table 2. Mean total worry score was 6.9 (SD 5.4) with a range of 0 to 16, indicating than on average there was a moderate level of pandemic-related worry. Mean total stress score was 6.6 (SD 3.3) with a possible range of 3–15, indicating a low to moderate level of stress. Sum worry and sum stress scores did not differ by gender or race (p’s > 0.05).

Pandemic-Related Life Changes

Eighty percent of participants reported having less contact with people outside of their homes relative to before the COVID-19 crisis. While most participants reported the quality of their relationships with family were unaffected (n = 93; 66.4%), 15.7% (n = 22) of participants reported that the quality of their family relationships were worse since the pandemic began. Nearly one-quarter of participants reported that relationships with friends were also affected (n = 33; 23.6%). One-third (n = 44, 31.4%) of participants worried about food running out and nearly half (n = 60, 44.7%) worried about the stability of their living situation (see Table 2).

Correlates of Change in Smoking Behavior

In bivariate analyses, none of the demographic variables correlated with the number of cigarettes smoked per day. However, two Covid-related variables were significantly associated with reporting changes in smoking level; worrying about food running out due to a lack of money (χ2 = 9.13, df 2, p = 0.01) and the sum score of Covid-19-related worry (rs = 0.19, p = 0.02), were associated with increased smoking. Exposure to COVID-19 was not associated with a change in smoking level (X2 = 0.92, df 2, p = 0.63). Also, there were no significant associations between changes in relationships, financial problems, or concern over the stability of their living situation and reported change in smoking level (see Table 3).

In the multivariable ordered logistic regression, worrying about food due to a lack of money and overall level of worry due to Covid were entered into the model together. The overall model was significant, X2 (2) = 10.78, p = 0.005. Worrying about food security was associated with greater odds of being in a higher smoking change category [OR 2.50; 95% CI (1.17, 5.36), p = 0.018], but the effect of total worry score was nonsignificant [OR 1.06; 95% CI (0.99, 1.13), p = 0.11].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of COVID-19 exposure, pandemic-related life changes, stress, and worry on smoking behaviors among those living with HIV, a group with high smoking prevalence rates and increased vulnerability to severe COVID-19 infection. Interestingly, our results indicate that while PWH experienced increased isolation from family and friends, and moderate levels of COVID-19-related anxiety and stress, their smoking behaviors remained fairly steady, their motivation to quit smoking was relatively unaffected, and few made a quit attempt. This is somewhat surprising since some studies of smokers in the general population reported greater fear related to COVID-19 effects, and this fear mediated the impact on behavioral intentions related to quitting smoking [24]. In one smoking cessation trial, higher perceived risk of COVID-19 was associated with increased interest in quitting smoking (AOR 1.72, 95% CI 1.01–2.92) [25]. In another study, smokers in the general population with higher perceived risk of COVID-19 infection were more than twice as likely to make a quit attempt (AOR 2.37, 95% CI 1.59, 3.55) [26]. A longitudinal study in the U.K. reported that over the 12 months of observations, 45% of smokers self-reported a quit attempt and more than one-quarter said it was due to COVID-19-related reasons [27]. Perhaps smokers with HIV already have high baseline levels of anxiety and stress (compared to the general population) and increased social isolation due to their HIV infection, so the pandemic did not move this underlying anxiety much more in a negative direction and did not impact their smoking behaviors. PWH may be a chronically stressed population that perhaps is less likely to be intimated by a new health challenge, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The NCI FOAs to support studies that test, develop, or adapt evidence-based smoking cessation interventions to reduce cigarette smoking rates in PWH was based on the premise that PWH who smoke may have unique treatment needs. Our findings provide further support that PWH who smoke are a unique group of smokers, and novel approaches to smoking cessation are likely required.

Several studies among general population smokers noted that smoking increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kalkhoran et al. reported that, while 45% of smokers reported no change in their cigarette smoking, 33% increased their level of cigarette smoking since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [28]. A second study found that increased smoking was associated with higher perceived pandemic-related stress (AOR 1.49, 95% CI 1.16–1.91) [25]. A study of Dutch smokers demonstrated that pandemic-related stress affected smokers in different ways. While some increased their level of smoking, others decreased [29]. While 25% of participants in our study reported increased smoking, the majority of smokers in our sample did not change their smoking level. While this may be due to the support they were receiving in their respective clinical trials for smoking cessation, it may also be related to financial constraints not experienced by other groups of smokers. PWH who smoke tend to be of lower socioeconomic status, as evidenced by their reports of concern that food would run out due to a lack of money. Nevertheless, our sample is different from the general population, and thus their behavior may be different.

Historically, a significant barrier to successful smoking cessation among PWH who smoke has been the use of cigarette smoking as a stress management strategy [2]. Among our sample, more than two-thirds of participants reported that smoking helped them stay calm during the COVID-19 crisis. This is similar to findings of Popova et al. who also reported that smokers in the general population believed that cigarettes help them deal with the stresses and challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic [30]. In a study of PWH living in the U.K., more than three-quarters reported feeling more anxious during the pandemic and one-fifth had suicidal thoughts. However, widespread resilience was also noted. More than 80% of study participants reported that the experience of living with HIV had given them the strength to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic [26]. Perhaps drawing on this history and focusing on resilience during smoking cessation counseling in PWH is a strategy that could improve cessation rates and sustained abstinence in this group of smokers. Some have suggested that a focus on resilience-based HIV care may enhance well-being among PWH during times of increased psychological stress [31]. Incorporating this approach in smoking cessation treatment with PWH may improve outcomes.

This study has several limitations. It was a cross-sectional examination and did not examine the effect of the pandemic on smoking behaviors over time. Participants who enrolled earlier in the pandemic and prior to the development of vaccines may have been affected differently compared to those who were enrolled later. Some findings, such as smoking level, may have been affected by recall bias. Finally, this sample is comprised of smokers with HIV who enrolled in smoking cessation trials during a pandemic and may not be generalizable to all smokers with HIV. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on smoking behaviors in PWH. Further, the survey was conducted with participants from three cities in the U.S. and was racially and ethnically diverse.

Conclusion

In summary, our study provides initial insight into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related stay-at-home order on PWH who smoke. Although a significant level of concern, stress, and worry were expressed, there was not a significant change in smoking behaviors or increased quit intentions noted. This is a somewhat unique and resistant group of smokers, highlighting the need for qualitative research to further understand smoking behavior and motivation to quit among PWH and suggesting the need for novel approaches.

Data Availability

Data may be available upon written request to the first author.

Code Availability

Code may be available upon written request to the first author.

References

McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93–4.

Cioe PA, Gordon REF, Guthrie KM, Freiberg MS, Kahler CW. Perceived barriers to smoking cessation and perceptions of electronic cigarettes among persons living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2018;30(11):1469–75.

Richards JM, Stipelman BA, Bornovalova MA, Daughters SB, Sinha R, Lejuez CW. Biological mechanisms underlying the relationship between stress and smoking: state of the science and directions for future work. Biol Psychol. 2011;88(1):1–12.

Commission FT. Federal trade commission cigarette report for 2020. 2021.

Ledgerwood DM, Yskes R. Smoking cessation for people living with HIV/AIDS: a literature review and synthesis. Nicot Tob Res. 2016;18(12):2177–84.

CDC. Current cigarette smoking among adults in the United States 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm.

Zyambo CM, Burkholder GA, Cropsey KL, Willig JH, Wilson CM, Gakumo CA, et al. Mental health disorders and alcohol use are associated with increased likelihood of smoking relapse among people living with HIV attending routine clinical care. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1409.

Shuter J, Bernstein SL, Moadel AB. Cigarette smoking behaviors and beliefs in persons living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(1):75–85.

Chew D, Steinberg MB, Thomas P, Swaminathan S, Hodder SL. Evaluation of a smoking cessation program for HIV infected individuals in an urban HIV clinic: challenges and lessons learned. AIDS Res Treat. 2014;2014: 237834.

Schnall R, Carcamo J, Porras T, Huang MC, Webb Hooper M. Use of the phase-based model of smoking treatment to guide intervention development for persons living with HIV who self-identify as African American tobacco smokers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1703.

Cooperman N. Current research on cigarette smoking among people with HIV. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:19–26.

Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, Wu Y, Huang J, Lian N, et al. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID-19: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1915–21.

Adrish M, Chilimuri S, Mantri N, Sun H, Zahid M, Gongati S, et al. Association of smoking status with outcomes in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2020;7(1):e000716.

Wang R, Pan M, Zhang X, Han M, Fan X, Zhao F, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of 125 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Fuyang, Anhui, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:421–8.

Bhaskaran B, Rentsch C, MacKenna B, Schultze A, Mehrkar A, Bates C, et al. HIV infection and COVID-19 death: a population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet HIV. 2021;8:e24–32.

Mellor MM, Bast AC, Jones NR, Roberts NW, Ordonez-Mena JM, Reith AJM, et al. Risk of adverse coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes for people living with HIV. AIDS. 2021;35(4):F1–10.

Ssentongo P, Heilbrunn ES, Ssentongo AE, Advani S, Chinchilli VM, Nunez JJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6283.

Hoeppner SS, Carlon HA, Kahler CW, Park ER, Darville A, Rohsenow DJ, et al. COVID-19 impact on smokers participating in smoking cessation trials: the experience of nondaily smokers participating in a smartphone app study. Telemed Rep. 2021;2(1):179–87.

Ashare RL, Bernstein SL, Schnoll R, Gross R, Catz SL, Cioe P, et al. The United States National Cancer Institute’s coordinated research effort on tobacco use as a major cause of morbidity and mortality among people with HIV. Nicot Tob Res. 2020;23(2):407–10.

Rosoff-Verbit Z, Logue-Chamberlain E, Fishman J, Audrain-McGovern J, Hawk L, Mahoney M, et al. The perceived impact of COVID-19 among treatment-seeking smokers: a mixed methods approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):505.

Cioe PA, Pinkston M, Tashima KT, Kahler CW. Peer navigation for smoking cessation in smokers with HIV: protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;110: 106435.

Quinn MH, Bauer AM, Fox EN, Hatzell J, Randle T, Purnell J, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized factorial clinical trial of pharmacogenetic and adherence optimization strategies to promote tobacco cessation among persons with HIV. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;110: 106410.

Fagerstrom K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom test for cigarette dependence. Nicot Tob Res. 2012;14(1):75–8.

Duong HT, Massey ZB, Churchill V, Popova L. Are smokers scared by COVID-19 risk? How fear and comparative optimism influence smokers’ intentions to take measures to quit smoking. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12): e0260478.

Rigotti NA, Chang Y, Regan S, Lee S, Kelley JHK, Davis E, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic reported by recently hospitalized participants in a smoking cessation trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(12):3786–93.

Pantelic M, Martin K, Fitzpatrick C, Nixon E, Tweed M, Spice W, et al. “I have the strength to get through this using my past experiences with HIV”: findings from a mixed-method survey of health outcomes, service accessibility, and psychosocial wellbeing among people living with HIV during the Covid-19 pandemic. AIDS Care. 2021;34(7):821–7.

Kale D, Perski O, Herbec A, Beard E, Shahab L. Changes in cigarette smoking and vaping in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: findings from baseline and 12-month follow up of HEBECO study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):630.

Kalkhoran SM, Levy DE, Rigotti NA. Smoking and E-cigarette use among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Prev Med. 2021;62(3):341–9.

Bommele J, Hopman P, Walters BH, Geboers C, Croes E, Fong GT, et al. The double-edged relationship between COVID-19 stress and smoking: implications for smoking cessation. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:63.

Popova L, Henderson K, Kute N, Singh-Looney M, Ashley DL, Reynolds RM, et al. “I’m bored and I’m stressed”: a qualitative study of exclusive smokers, ENDS users, and transitioning smokers or ENDS users in the time of COVID-19. Nicot Tob Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab199/6381659.

Brown LL, Martin EG, Knudsen HK, Gotham HJ, Garner BR. Resilience-focused HIV care to promote psychological well-being during COVID-19 and other catastrophes. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 705573.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Suzanne Sales for her contributions to the codebook development, dataset merging, and data management. NCI staff reviewed a draft of this manuscript to provide feedback on the initiative language but had no influence over the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

This work is supported by the following Grants from the National Cancer Institute: R21CA243906, R21CA243911 and R01CA243914. This work was also supported by the Penn Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), (P30 AI 045008), Penn Mental Health AIDS Research Center (PMHARC) (P30 MH 097488). This work was facilitated by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PAC and RS contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by PAC, RS, and CWK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PAC and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Drs. Cioe, Hoeppner, Hitsman, Pinkston, Tashima, and Kahler have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. Dr. Schnoll received medication and placebo free of charge from Pfizer for clinical trials and has provided consultation to Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Curaleaf. Dr. Ashare received an investigator-initiated grant from Novo Nordisk, Inc for a study unrelated to the current project. Dr. Vilardaga is the principal investigator in an industry trial study funded by Happify Inc. Dr. Gross serves on a DSMB for a Pfizer medication unrelated to smoking or HIV.

Ethical Approval

Approval was obtained by Institutional Review Boards at Brown University and the University of Pennsylvania.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cioe, P.A., Schnoll, R., Hoeppner, B.B. et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Stress, Isolation, Smoking Behaviors, and Motivation to Quit in People with HIV Who Smoke. AIDS Behav 27, 1862–1869 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03917-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03917-w