Abstract

This study evaluates associations between online social networking and sexual health behaviors among homeless youth in Los Angeles. We analyzed survey data from 201 homeless youth accessing services at a Los Angeles agency. Multivariate (regression and logistic) models assessed whether use of (and topics discussed on) online social networking technologies affect HIV knowledge, sexual risk behaviors, and testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). One set of results suggests that using online social networks for partner seeking (compared to not using the networks for seeking partners) is associated with increased sexual risk behaviors. Supporting data suggest that (1) using online social networks to talk about safe sex is associated with an increased likelihood of having met a recent sex partner online, and (2) having online sex partners and talking to friends on online social networks about drugs and partying is associated with increased exchange sex. However, results also suggest that online social network usage is associated with increased knowledge and HIV/STI prevention among homeless youth: (1) using online social networks to talk about love and safe sex is associated with increased knowledge about HIV, (2) using the networks to talk about love is associated with decreased exchange sex, and (3) merely being a member of an online social network is associated with increased likelihood of having previously tested for STIs. Taken together, this study suggests that online social networking and the topics discussed on these networks can potentially increase and decrease sexual risk behaviors depending on how the networks are used. Developing sexual health services and interventions on online social networks could reduce sexual risk behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) disproportionately affect homeless youth. Estimates of HIV in homeless youth range from 2 to 11%, leaving homeless youth at 2–10 times the risk of other adolescents in the United States [1–4]. The presence of STIs among homeless youth is associated with higher rates of sexual risk behaviors (such as unprotected sexual intercourse) and lower rates of testing for HIV and other STIs [5, 6]. Understanding innovative methods that can increase or decrease STI transmission is important in preventing the spread of HIV and other STIs among homeless youth.

Technologies such as the Internet and online social networks may play an important role in facilitating or inhibiting sexual risk behaviors, especially among homeless youth [7–10]. Research on technologies and STI/sexual risk behaviors has typically focused on general Internet and chat-room use among adult populations. This research has looked at the role that the Internet plays in adult sexual risk behaviors [11, 12]; methods of using the Internet to reduce the stigma associated with partner seeking among men who have sex with men (MSM) [13]; methods of using the Internet for HIV/STI study recruitment [14–16]; and methods of using the Internet to deliver HIV/STI interventions and treatments [17]. Results from some of these studies have suggested that people who use the Internet for finding sex partners may be at the highest risk of contracting HIV and STIs. For example, McFarlane et al., [18] reported that, compared to people who do not seek sex on the Internet, “Internet sex seekers” tend to have more frequent anal sex, more previously diagnosed STIs, more sexual exposure to men, greater numbers of sex partners, and higher numbers of sex partners known to be HIV positive.

Surprisingly, the majority of homeless youth frequently access the Internet (over 96%) [19] and those who do might also be more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors [9]. Recent research suggests that homeless youth access the Internet on a daily basis in order to communicate with street and home-based peers, family members, service organizations, and potential employers [19]. Confirming the results of Internet use and sexual risk behaviors among adult populations, research on homeless youth who use the Internet also engage in increased rates of sexual risk behaviors. In fact, one study suggests that homeless youth who practiced exchange sex were 18 times more likely to have found sex partners online [19]. Studying associations between technologies and sexual risk behaviors among youth might be particularly relevant because youth often use technologies in order to socialize, search for information about STIs, communicate with sexual partners about condom use and sexual behaviors, and find out how to get tested for HIV and other STIs [20, 21].

While the bulk of the research on technologies and sexual risk behaviors has focused on Internet use, online social networking technologies, such as Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter, are a new and growing form of online communication among youth that have only begun to be studied related to STI prevention and sexual risk behaviors [8, 22–25]. Online social networks allow users to communicate with others through virtual networks where they can have an online profile, send emails, pictures, chat, and play games [26].

Research suggests that youth often use social networking technologies for flirting and building romantic and sexual relationships [9, 27], and it is likely that homeless youth use online social networking technologies for this same purpose. However, it is unknown what impact these virtual networks have on homeless youths’ sexual risk behaviors, and whether their purpose of communication on these networks may be associated with risk behaviors. On one hand, online social networks might increase sexual risk behaviors as suggested by research showing that youth often engage in cybersex on the Internet and that Internet sex-seekers engage in increased sexual risk behaviors [28–30]. Online social network users might also be more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors because online social networks are designed and used for socializing, including the ability to meet potential romantic others [22, 27, 31]. However, online social network usage could also potentially decrease sexual risk behaviors as youth use online social networks to communicate with others about sexual health, discuss sexual experiences, and learn about HIV and STI prevention [8, 24]. Furthermore, researchers and organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have begun to develop information portals that use online social networks to improve knowledge about HIV and STIs and attempt to reduce sexual risk behaviors [8, 25]. Taken together, online social networks and the way they are used could potentially increase and/or decrease sexual risk behaviors.

The present analysis looks at the relationship between online social network usage and HIV risk behaviors, knowledge about HIV, and STI testing among urban, homeless, youth, a group at extreme high risk for HIV/AIDS who has been raised using online social networks and may be at greater risk for HIV because of their use on these networks.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

A purposive sample of 201 youth was recruited between June 1 and June 22, 2009 in Los Angeles, California at one drop-in agency serving homeless youth. Any client, age 13 to 24, receiving services at the agency was eligible to participate. In June 2009, the agency saw 530 individual youth (34% female, 65% male, and 1.4% transgender. 45% African American, 20% Caucasian, 20% Latino, 1.3% Asian/Pacific Islander, 9% mixed ethnicity, and 5.3% other). Average age was 21.4 years. Recruitment was conducted to match gender, age, and ethnicity of the client population receiving services.

Youth voluntarily signed up to participate in the survey at the same time they signed up to receive services at the agency (e.g. a shower, clothing, case management). A consistent set of two research staff members were responsible for all recruitment and assessment to prevent youth completing the survey multiple times. During recruitment, the research team regularly checked enrollment based on age, gender, and ethnicity and solicited participation from under-represented groups as needed.

For youth 13–17 years old a waiver of parental permission was obtained. All youth accessing services at the agency were homeless or precariously housed (i.e., unaccompanied minors). Because the survey was anonymous a waiver of signed consent was obtained to allow the data to be completely anonymous and protect the privacy of the subjects. All participants were provided with an information sheet that explained the study procedures and their rights as human subjects in research. Research staff received approximately 40 h of training, including lectures, role-playing, mock surveys, ethics training, and emergency procedures.

All surveys were conducted in a private space at the agency. The survey was anonymous and was a computer administered self-interview, where youth answered survey items pertaining to social networking technology use, demographics, sex and drug risk taking, living situation, service utilization, and mental health. The survey lasted approximately 60 min. All participants received a $20 gift card as compensation for their time. Survey items and procedures were approved by the University of Southern California’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

All survey items were self-reported and included information regarding demographics (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender) Internet and online social network usage (including the amount of time spent using online social networks, the types of networks used, and the topics of conversations when using online social networks), sexual risk behaviors (including the number of sexual partners found online in the past 3 months, and history of exchanging sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay), lifetime history of STI testing, and knowledge about HIV and STI’s.

Years homeless was coded from subtracting adolescent’s current age from their self-reported age of first homeless experience. Unsheltered was coded 1 for youth who reported “street, squat, abandoned building” as their current residence. Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual (GLB) was based on self-reported sexual orientation and coded as 1 if Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual or 0 if self-reported Heterosexual or Questioning. STI test was based on “Have you been tested for any [other than HIV] sexually transmitted disease (for example syphilis, gonorrhea, Chlamydia, HPV) in the past 6 months?” coded 1 for yes, 0 for no.

Had sex with online partner and exchanged sex were limited to participants who had had sex (n = 158). Had sex with online partner was based on the item “How many of these sex partners [from the past 3 months] did you meet online?” This number (a continuous variable) was dummy-coded as 0 = 0 partners or 1 = greater than 0 partners. Exchanged sex was based on the item “In the last 3 months have you exchanged for sex money, drugs, a place to stay, food or meals, or anything else?” coded 1 for no, 0 for yes.

The HIV knowledge questions were composed of 22 true/false items listing statements related to HIV/STI’s (e.g., “HIV is caused by a virus” and “Most people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States are men who have sex with other men”).

Data Analysis

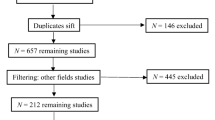

Descriptive statistics were presented on demographics, social network usage, and HIV risk behaviors. For the variables related to topics discussed on online social networks, we created a correlation matrix and removed items that had a correlation over 0.6. Regression analysis was used to test for predictors of HIV knowledge (based on an index based on the 22 HIV-related items). Logistic regression analysis was used to test for predictors of meeting online sex partners; exchanging drugs, alcohol, money, food, or a place to stay for sex; and past history of STI testing. All models included the following demographic variables: age, male, African American, Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual, years homeless, unsheltered, and have previously had sex with partners met online. STATA software was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

Table 1 provides demographic characteristics about the sample. Participants were 201 homeless youth accessing services at the agency and were predominantly African American or White, unemployed, male, heterosexual, and high school graduates or holding a GED or higher degree. The majority of participants in the sample used online social networks almost every week (78.75%) and were particularly likely to use MySpace and/or Facebook. When using online social networks, participants frequently communicated with others about videos; drinking, drugs and parties; sex; love and relationships; being homeless; and school experiences.

Table 2 displays the results of overall sexual risk behaviors and knowledge about HIV among the sample. The majority of participants (79.35%) had previously tested for sexual transmitted infections (STIs). Over 20% of participants who had had sex met a sexual partner within the last 3 months online, and over 10% had exchanged sex for food, drugs, or a place to stay. We found overall differences on rates of sex with online partners, exchanged sex, and STI testing by gender and MSM (Table 3).

Table 4 displays the results of the multivariate analysis looking at associations between online social network usage and online sexual partners, exchanged sex and STI testing. Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual participants (compared to heterosexual and questioning participants) were more likely to have used the Internet to meet one of their sex partners in the past 3 months. Participants who used online social networks to talk to their peers about safe sex were more likely (than those who did not talk about these topics on online social networks) to have used the Internet to meet sex partners in the past 3 months. Female participants and participants who had sex in the past 3 months with people they met online were more likely to have had exchanged money, drugs, a place to stay, food, or other things for sex. Homeless youth who had talked to their peers on online social networks about drinking and drugs were also more likely to have had exchanged sex. Those who used the network to talk about love were less likely to have had exchanged sex.

Males (compared to females) and participants who did not use online social networks (compared to online social network users) were less likely to have previously tested for STI’s. In a sub-analysis looking at STI testing by type of social network, we found that MySpace users were more likely to have tested for STI’s compared to non-MySpace users.

The 22-true/false HIV knowledge items were summed to create an HIV knowledge index score. A correct response on the item was given a score of 1; an incorrect response was given a score of 0. The sum of the correct answers was used to create the index (0–22 scale; 0 = least correct answers related to HIV, 22 = greatest number of correct responses about HIV. On average, participants fell in the middle of the range of scores regarding their HIV knowledge.

Participants who talked to peers on online social networks about either love or safe sex scored higher on the HIV knowledge index than those who did not talk about these topics. Those who talked to others on online social networks about love scored lower on the HIV knowledge index than those who did not talk about this topic (Table 5).

Discussion

Results suggest that online social networks usage can be associated with both potential increases and decreases in HIV/STI risk behaviors in homeless youth. Among 201 homeless youth, the majority of participants used online social networks almost every week and had previously tested for STIs. Over 20% of sexually active participants found a recent sexual partner online, and over 10% had exchanged sex for food, drugs, food, or a place to stay. One set of results suggests that using online social networks for partner seeking (compared to not using the networks for seeking partners) can be associated with an increase sexual risk behaviors. Supporting data reveal that (1) using online social networks to talk about safe sex was associated with an increased likelihood of having met a recent sex partner online, and (2) having had online sex partners and talking to friends on online social networks about drugs and partying was associated with increased rates of exchanged sex.

Results also suggest that online social network usage is associated with increased knowledge and HIV/STI prevention behaviors among homeless youth. Supporting data suggest that (1) using online social networks to talk about love and safe sex is associated with increased knowledge about HIV, (2) using the networks to talk about love is associated with decreased exchange sex, and (3) merely being a member of an online social network is associated with increased likelihood of having previously tested for STIs.

Data from this analysis therefore provide two possibly complementary stories. First, people who use online social networks for sex-related conversations (compared to those who do not talk about sex-related topics) might be more likely to engage in certain sexual risk behaviors that have been found to be associated with increased HIV/STI risk, such as finding sex partners online. However, people who use online social networks both for general use as well as to talk about love and/or safe sex might be more knowledgeable about STIs, aware of their possible risk, less likely to practice exchanged sex, and more likely to get tested.

These findings suggest that online social networks are popular among homeless youth, and that they can be used as a tool for sexual health interventions. As online social networks continue to increase, these networks could potentially increase sexual risk behaviors by facilitating an easy way to meet new sex partners. They could also potentially decrease homeless youths’ sexual risk behaviors if the networks are used as effective sexual health communication and information portals. For example, along with traditional face-to-face methods, agency outreach can use online social networking technologies to set up informational communication pages where they can chat, send messages and Internet links, and offer general resources and help for homeless youth. Health agencies such as the CDC and AIDS.gov have begun using online social networks to inform users about their STI risks and the services available to them. The current findings support the possibility that these types of HIV/STI online social network portals could potentially increase online social network users HIV knowledge and increase rates of STI testing. As networks continue to grow and people continue to use the networks to find sex partners, it becomes increasingly important that health researchers and agencies use these virtual networks to inform users about their risks and offer information on how they can protect themselves.

Provider outreach methods on online social networking technologies may differ based on the type of online social networking technology. For example, on Facebook less than a year ago, communication at the group level was almost entirely done through sending messages or wall posts through Facebook groups. Based upon Facebook changes this year, messages can now be delivered through additional methods such creating an organization or non-profit page and getting others on the network to say that they like the organization or an idea that was posted. This method allows information to be scaled to a large group quickly [32]. Most recently, communication can be initiated on Facebook through posting a question to spark responses and thoughts from others. Methods of outreach at the population level may also differ by online social network. For example, MySpace has been known to have a larger number of people from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds and has maintained an active base of youth and musicians on the network [33]. Taken together, multiple methods exist for targeting homeless youth and other at risk populations through online social networking technologies. These methods should be based on the attributes of the social network and the trends in participation. In order to best reach these populations, future research should focus on understanding the available methods of communication on each online social network and determine whether those methods are appropriate for the given population.

Results also suggest that Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual homeless youth are more likely than non-GLB homeless youth to have met a previous sex partner online. However, it is not entirely clear whether MSM online partner seeking is associated with increased HIV/STI risk and increased transmission. For instance, MSM who search for sexual partners online are more likely to have unprotected sex, and therefore may be at greater risk for receiving or transmitting HIV and STIs [11]. Yet, the increased rates of online partner seeking among GLB may be the result of GLB desire to avoid stigma when seeking partners [9, 12], and could therefore potentially lead to a larger pool of eligible sexual partners who are aware of their sexual risk and using the Internet only to avoid stigma [34]. Future research can address this question.

Study limitations are based on the observational study design and the purposive sample of homeless youth from a drop-in agency. One limitation is that the study used self-report measures rather than testing actual behavior, making it difficult to know whether participant reports of sexual behaviors were accurate. However, self-report measurements are often used and found to be accurate [28, 29] and measuring actual sexual behavior could be invasive. Next, the sample of homeless youth might not be able to generalize to other online social network users. However, because homeless youth are at increased risk for HIV relative to other youth, we feel that this is an important population to target. Additionally, because these youth are often communicating with other housed friends, they may share similarities of online social network usage behavior with housed youth. Future studies may help to determine whether homeless youths’ online social network sexual health behaviors differ from other youth and other populations. Finally, although results suggest a link between online social network usage and sexual risk, our sample and method of data collection does not allow for causal inference. It is possible that youth who are engaging in risk online are potentially finding a new venue to engage in sexual risk behaviors. It is important to conduct additional research to determine whether youth seeking sex online are greater risk than those who seek sex from offline methods, and to determine whether youth are using online social networking technologies as an additional venue to engage in sexual risk behaviors.

Conclusion

As online social network usage continues to increase, users will develop innovative and easier ways to find sex partners online. In order to prevent the spread of HIV and other STIs, it is important to understand the role that online social networking technologies play in the lives of people who face disproportionate risk. The current findings suggest that use of online social networks can be associated with both increases and decreases in sexual risk behavior. These findings suggest that it is imperative that health care providers and organizations use online social networks for sexual health communication in order to decrease sexual risk behaviors and increase HIV/STI testing. Little research has been done in this area, making it important for researchers to begin studying how this new technology impacts sexual health.

References

National Network for Youth. Toolkit for youth workers: fact sheet. Runaway and homeless youth. Washington, DC.

Stricof RL, Kennedy J, Nattell TC, Weisfuse IB, Novick LF. HIV seroprevalence in a facility for runaway and homeless adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(Suppl):50–3.

Schalwitz J, Goulart M, Dunnigan K, Flannery D, editors. Prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and HIV in a homeless youth medical clinic in San Francisco. VI International conference on AIDS, San Francisco; 1990.

Pfeifer R, Oliver J. A study of HIV seroprevalence in a group of homeless youth in Hollywood, California. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20(5):339–42.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Song J, Gwadz M, Lee M, Rossem RV, Koopman C. Reductions in HIV risk among runaway youth. Prev Sci. 2003;4(3):173–87.

Ennett ST, Federman EB, Bailey SL, Ringwalt CL, Hubbard ML. HIV-risk behaviors associated with homelessness characteristics in youth. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(5):344–53.

Bull S, Pratte K, Whitesell N, Rietmeijer C, McFarlane M. Effects of an Internet-based intervention for HIV prevention: the Youthnet trials. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(3):474–87.

Rice E, Tulbert E, Young SD. Interactive communications technology use among homeless youth. J Adolesc Health. Under review.

Subrahmanyam K, Greenfield P. Online communication and adolescent relationships. Future Child. 2008;18:119–46.

Rice E. The positive role of social networks and social networking technology in the condom using behaviors of homeless youth. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(4):588–95.

Liau A, Millett G, Marks G. Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(9):576–84.

Bolding G, Davis M, Hart G, Sherr L, Elford J. Where young MSM meet their first sexual partner: the role of the Internet. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(4):522–6.

Davis M, Hart G, Bolding G, Sherr L, Elford J. Sex and the Internet: gay men, risk reduction and serostatus. Cult Health Sex. 2006;8(2):161–74.

Fernandez MI, Varga LM, Perrino T, et al. The Internet as recruitment tool for HIV studies: viable strategy for reaching at-risk Hispanic MSM in Miami? AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):953–63.

Rosser B, Miner M, Bockting W, et al. HIV risk and the Internet: results of the Men’s INTernet Sex (MINTS) Study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):746–56.

Bowen A, Williams M, Horvath K. Using the Internet to recruit rural MSM for HIV risk assessment: sampling issues. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(3):311–9.

Bowen AM, Horvath K, Williams ML. A randomized control trial of Internet-delivered HIV prevention targeting rural MSM. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(1):120–7.

McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA. 2000;284(4):443–6.

Rice E, Monro W, Barman-Adhikari A, Young SD. Internet use, social networking, and HIV/AIDS risk for homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.016.

Gross EF. Adolescent Internet use: what we expect, what teens report. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2004;25(6):633–49.

Lenhart A, Madden M. Social networking websites and teens: an overview. 2007: Available from: www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_SNS_Data_Memo_Jan_2007.pdf.

Young S, Jordan A. The influence of Facebook pictures on college students’ sexual health behaviors. In: Fogg B, editor. The psychology of Facebook. Stanford, CA: Stanford University (in press).

Gordon R, Bjorklund N, Smith R, Blyden E. Halting HIV/AIDS with avatars and havatars: a virtual world approach to modelling epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(Supp 1):S13.

Moreno MA, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, Brito TE, Christakis DA. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: prevalence and associations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(1):27–34.

Moreno MA, VanderStoep A, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, Kurth A, Christakis DA. Reducing at-risk adolescents’ display of risk behavior on a social networking web site: a randomized controlled pilot intervention trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(1):35–41.

Facebook.com. Facebook. 2009. Available from: www.facebook.com. Cited 20 October 2009.

Young SD, Dutta D, Dommety G. Extrapolating psychological insights from Facebook profiles. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12(3):347–50.

Bolding G, Davis M, Hart G, Sherr L, Elford J. Gay men who look for sex on the Internet: is there more HIV/STI risk with online partners? AIDS. 2005;19(9):961–8.

McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. Young adults on the Internet: risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases and HIV(1). J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(1):11–6.

Vybiral Z, Smahel D, Divinovna R. Growing up in virtual reality: adolescents and the Internet. In: Mares P, editor. Society, reproduction, and contemporary challenges. Brno: Barrister & Principal; 2004. p. 169–88.

Clemmit M. Cyber socializing: are Internet sites like MySpace potentially dangerous? CQ Researcher. 2006;16:625–48.

Facebook.com. Facebook. 2010. Available from: www.facebook.com. Cited 7 August 2010.

Wilkinson D, Thelwall M. Social network site changes over time: the case of MySpace. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2010. doi:10.1002/asi.21397.

Pascoe CJ. Keynote lecture: virtual sex ed: youth, race, sex, and new media. Chicago Uo. Chicago: Section of Family Planning and Contraceptive Research; 2009.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, S.D., Rice, E. Online Social Networking Technologies, HIV Knowledge, and Sexual Risk and Testing Behaviors Among Homeless Youth. AIDS Behav 15, 253–260 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9810-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9810-0