Abstract

This paper studies contribution of capital deepening, technological progress and efficiency improvement to economic growth while focusing on cross-country data, and thus finds itself at the crossroads of growth and development accounting. We take a production frontier approach to growth accounting and choose DEA as the frontier estimation method. To explore the effects that windfall gains from natural resource use have on growth, output data are corrected for pure natural resource rents—part of GDP figures not earned by either labor or capital. Taking into account countries’ natural resources, we find that in the two decades from 1970 to 1990 the average contribution of technological catch-up to per worker output growth was, if anything, negative on the worldwide scale and this trend continued till the mid 1990ies. Analysis of efficiency estimates also shows a possible change over the period of 1970–1990 in the effect of natural resources on country’s performance

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, Coelli et al. (2005) for an overview of the various methods

Given the CRS assumption, the alternative definition in per worker terms is y t =f t (k t )

s is observed in the data every 5 years. Since s moves slowly over time, a quinquennial observation can plausibly be employed for nearby dates as well.

See World Bank (2006) for a broader discussion of the genuine saving concept. World Development Indicators (WDI) database reports energy and mineral rent as percentage of GNI. To express rents in terms of GDP, we multiply them by the ratio of GNI to GDP in the given year.

Calculations were carried out using the DEAFrontier software developed by Joe Zhu at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

For comparison in Table 6 a 25 year period from 1971 to 1996 is used. Estimates of the capital stock, K, are then generated using the perpetual inventory equation Kt = It + (1−δ)Kt−1, where It is investment, measured from PWT6.1 as RGDPL · POP · KI, where RGDPL is real income per capita obtained with the Laspeyres method, POP is the population, and KI is the investment share in total income.

Following the literature, for example Caselli (2005), depreciation rate δ is set to 0.06 and the initial capital stock K0 is computed as I 0 /(g+δ), where I 0 is the value of the investment series in the first year it is available, and g is the average geometric growth rate for the investment series between the first year with available data and 1970.

Hicks neutrality would see production frontier shift upwards without change of shape.

It may appear plausible if one allows for a broader definition of technology incorporating institutional and systemic component. For instance, Blanchard and Kremer (1997) explain the sharp economic decline of the whole bloc of ex-socialist economies during the 1990s by the collapse of the crucial institutional element of production which led to disorganization. Precluding technological regress in the DEA analysis comparing these countries would be pointless, since a clear technological regress was indeed present in this middle income part of the world. The same argument can be extended to many African countries which historically represent the lower-income part of the world and where certain institutions present in the 1960s were simply not in place any more in the 1990s. On the other hand, while the suggested “sequential production set” approach does insure against technological regress in the data, it strengthens and prolongs the effect of “positive outliers” i.e. country observations with overestimated production per worker.

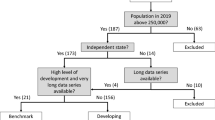

Due to data limitations, in our core samples we focus on two time periods, 1970/1971 and 1990 and changes over these two decades. For comparison in Table 5 we consider a 25-year interval from 1971 to 1996, whereby the sequential production set is constructed over three year observations: 1971, 1990, 1996

although this bimodality gets smoothed in panel (2*) where differences in human capital are taken into account.

The Economic Freedom index provided by the Frazer Institute measures the degree of economic freedom present in five major areas: government size, property rights, access to financial markets and to international trade and state regulation of business See Gwartney and Lawson (2007) for detailed overview. In total, the index is comprised of 42 distinct variables, each placed on a scale from zero to 10, and is proven good approximation of institutional quality.

Patent count is the number of patents granted to the respective countries’ residents by the US Patent and Trademark Organization (USPTO) and is a way to measure countries’ innovative activity. The data are taken from World Bank’s Innovation and development Database, described in Lederman and Saenz (2005).

as established in a recent paper by Simar and Wilson (2007) for proper inference a double bootstrap procedure should complement truncated regression, but in our case the important thing is that these regressions rule out a significant negative impact of rents on efficiency in 1970/1971.

Diewert (1992) demonstrates the many favourable statistical and economic theoretic properties of the Fisher index which lead to the name.

And the fact that output per worker growth over the 5 years from 1965 to 1970 appears to be almost half of the total growth over the 25 year period from 1965 to 1990 raises concern about the validity of the 1965 data used in Kumar and Russell (2002).

References

Afriat S (1972) Efficiency estimation of production functions. Int Econ Rev 13(3):568–98

Barro RJ, Lee J (2001) International data on educational attainment: Updates and implications. Oxf Econ Pap 53(3):541–563

Blanchard O, Kremer M (1997) Disorganization. Q J Econ 112(4):1091–1126

Caselli F (2005) Accounting for cross-country income differences. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S (eds) Handbook of economic growth. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Coelli TJ, Prasada Rao DS, O’Donnell CJ, Battese GE (2005) An introduction to efficiency and productivity analysis 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Diewert WE (1980) Capital and the theory of productivity measurement. Am Econ Rev 70:260–67

Diewert WE (1992) Fisher ideal output, input and productivity indexes revisited. Journal of Productivity Analysis 3(3):211–48

Easterly W, Levine R (2001) It’s not factor accumulation: Stylized facts and growth models”. World Bank econ rev 15(2):177–219

Färe R, Grosskopf S, Norris M, Zhang Z (1994) Productivity growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in industrialized countries. Am Econ Rev 84(1):66–83

Farell MJ (1957) The measurement of productive efficiency. J R Stat Soc, Series A, General 120(3):253–82

Gwartney J, Lawson R (2007) Economic freedom of the world bulletin: 2007

Hall RE, Jones CI (1999) Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Q J Econ 114(1):83–116

Henderson DJ, Russell RR (2005) Human capital and convergence: a production frontier approach. Int Econ Rev 46(4):1167–1205

Kumar S, Russell RR (2002) Technological change, technological catch-up, and capital deepening: relative contributions to growth and convergence. Am Econ Rev 92(3):527–548

Lederman D, Saenz L (2005) Innovation and development around the world, 1960-2000. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3774

Rodrik D (1999) Where did all the growth go? External shocks, social conflict, and growth collapses. J econ growth 4(4):385–412

Sachs JD, Warner AM (1995) Natural resource abundance and economic growth NBER Working Paper No. 5398

Simar L, Wilson PW (2007) Estimation and inference in two-stage, semi-parametric models of production processes. J econom 136(1):31–64 Elsevier

Summers R, Heston A (1991) The Penn world table (Mark 5): an expanded set of international comparisons, 1950–1988. Q J Econ 106(2):327–68

World Bank (2006) (ed.by Kirk Hamilton) Where is the wealth of nations? Measuring Capital for the 21st century. World Bank publication

Acknowledgements

The author renders thanks for helpful comments and suggestions to the participants of International Wuppertal Colloquium on Sustainable Growth, Resource Productivity and Sustainable Industrial Policy held 17–19 September 2008 at Wuppertal University, Nordic Conference in Development Economics 2008 held 16–17 June at IIES at Stockholm University and Monte Verità Conference on Sustainable Resource Use and Economic Dynamics held on 2–5 June 2008. All errors remain my own responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Merkina, N. Technological catch-up or resource rents?. Int Econ Econ Policy 6, 59–82 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-009-0127-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-009-0127-2