Summary

Background

The cause of pericarditis is manifold. It can occur as a result of various diseases but may also be triggered by drugs. However, the data on drug-induced pericarditis are still scarce.

Case report

A 64-year-old female hypertensive patient with rheumatoid arthritis for 20 years presented with thoracic pain and recurrent pericardial and pleural effusions. For treatment of the recurrent effusions, the patient received glucocorticoids and colchicine in addition to the basic rheumatoid arthritis therapy, and treatment has only recently been expanded to include etanercept. On admission, she complained of malaise, dysphagia, and blood pressure was 85/55 mm Hg. She was normofrequent with elevated inflammatory parameters. On trans-thoracal echocardiography (TTE) and computer-tomography (CT), there was a 3-cm non-floating structure in the entire circumference of the pericardium. The indication for pericardiectomy was given because of hemodynamic impairment. After incision of the pericardium, 250 ml of a brown-reddish fluid drained, with brown crumbly necrotic masses visible underneath. Histopathologic findings revealed vasculitis-related chronic fibrinous pericarditis with vasculitic changes. A subclinical infection with Staphylococcus aureus was detectable by PCR analysis.

Conclusion

Based on the fact that tumor necrosis factor blockers can induce vasculitis, etanercept might have been responsible for the exacerbation of pericarditis. The underlying rheumatoid arthritis could also be considered as a trigger. The detection of Staphylococcus aureus DNA in the pericardium and the exacerbation of pericarditis could be attributed to secondary vasculitis after an infection with S. aureus, whereas the tendency to infection due to humoral immunodeficiency after years of immunosuppressive therapy has to be discussed as a trigger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pericarditis has a hospitalization rate of 3.32 and an incidence of 27.7 per 100,000 person-years and accounts for only about 0.2% of all cardiac-related hospitalizations [1]. Triggers may include infections (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic) as well as noninfectious triggers (autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, metabolic disorders, and iatrogenic and traumatic causes) [2]. In very rare cases, drugs, especially chemotherapeutic agents and rarely penicillins, can also lead to the development of pericarditis.

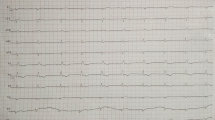

To diagnose pericarditis, more than two of the following parameters must be present: chest pain (improvement by sitting upright, leaning forward), pericardial rubbing, typical ECG changes, new-onset or worsening pericardial effusion, elevation of infectious parameters, evidence of pericardial inflammation by imaging. Prognostically, fever, recurrent hemodynamically effective pericardial effusions, and nonresponse to NSAID therapy [3] are associated with prolonged hospital stays. Treatment is predominantly by anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, colchicine, and glucocorticoids) as well as treatment of the underlying disease [4]. However, the data regarding drug-induced pericarditis are sparse [5].

Case report

A 64-year-old female hypertensive patient with increasing dyspnea and unspecific thoracic pain had had rheumatoid arthritis for 20 years, which was treated with methotrexate, leflunomide, and abatacept as mono- and combination therapy. Due to continued disease activity, the patient received a combination therapy of methotrexate with etanercept 6 months ago. Bilateral pneumonia with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia was successfully treated. The patient had had recurrent pericardial and pleural effusions for years, which were attributed to rheumatoid arthritis activity. For treatment of the recurrent effusions, the patient received glucocorticoids as well as colchicine in addition to the basic rheumatoid arthritis therapy. On admission, she complained of malaise, vomiting, and dysphagia; blood pressure was 85/55 mm Hg, she was normofrequent, inflammatory parameters were elevated. On TTE and CT, there was a 3-cm non-floating structure in the entire circumference of the pericardium, thickened to 3 mm (Fig. 1). The indication for partial pericardiectomy was given because of hemodynamic impairment. Six weeks earlier, a subxiphoid pericardiotomy had been performed with nonspecific histology and negative cytology. After incision of the pericardium, 250 ml of a brown-reddish fluid drained, with brown crumbly necrotic masses visible underneath (Fig. 2). The pericardium was resected except for the dorsal portions. After pericardiectomy, the patient remained free of cardiac symptoms for 12 months (to date). Immunosuppressive therapy was significantly reduced, and the patient last received only immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory therapy with hydroxychloroquine and low-dose methylprednisolone. Since bilateral pneumonia and subsequently osteomyelitis occurred during this therapy, an immunodeficiency was suspected. This was confirmed and a substitution therapy with immunoglobulins was initiated.

Diagnosis

Histopathologic findings revealed vasculitis-related chronic fibrinous pericarditis with vasculitic changes in the small vessels without evidence of malignancy. Cytologically, there were no pathologic findings; subclinical infection with Staphylococcus aureus was detectable by PCR analysis. However, microbiologically, no evidence of florid infection was found.

Discussion

Based on the fact that tumor necrosis factor blockers can induce vasculitis and lupus-like polyserositis, etanercept might have been responsible for the exacerbation of pericarditis. [6, 7]. The underlying rheumatoid arthritis could also be considered as a trigger of pericarditis since the incidence of pericarditis is reported in the literature as up to 27% [8]. Based on the detection of Staphylococcus aureus DNA in the pericardium, the S. aureus bacteremia that took place, and the small vessel vasculitis that was detected, the exacerbation of pericarditis was attributed to secondary vasculitis after an infection with S. aureus, whereas the tendency to infection due to humoral immunodeficiency after years of immunosuppressive therapy including continuous glucocorticoid application has to be discussed as a trigger.

References

Kytö V, Sipilä J, Rautava P. Clinical profile and influences on outcomes in patients hospitalized for acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2014;130(18):1601–6.

Imazio M, Brucato A, Derosa FG, Lestuzzi C, Bombana E, Scipione F, et al. Aetiological diagnosis in acute and recurrent pericarditis: when and how. J Cardiovasc Med. 2009;10(3):217–30.

Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, Ierna S, Demarie D, Ghisio A, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115(21):2739–44.

Mayosi BM, Ntsekhe M, Bosch J, Pandie S, Jung H, Gumedze F, et al. Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in tuberculous pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(12):1121–30.

Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Barón-Esquivias G, Bogaert J, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921–64.

Galaria NA, Werth VP, Schumacher HR. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis due to etanercept. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(8):2041–4.

De Bandt M. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):235.

Koivuniemi R, Paimela L, Suomalainen R, Leirisalo-Repo M. Cardiovascular diseases in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2013;42(2):131–5.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

C. Nebert, C. Mayer, B. Zirngast, L. Moser, P. Rainer, M. D’Orazio, J. Hermann, V. Stangl, and H. Mächler declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Informed consent was obtained from the patient in this case report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nebert, C., Mayer, C., Zirngast, B. et al. Case report: the rare clinical picture of vasculitis of the pericardium in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Surg 54, 173–175 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-022-00755-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-022-00755-x