Summary

Background

Introduced in the mid-1990s, minimally invasive pancreatic surgery (MIPS) developed slowly over the next two decades, and its real-life benefits remained unclear.

Methods

In this review, the current status and evidence on the most common types of MIPS, such as minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy (MIPD), distal pancreatectomy, enucleation, and central pancreatectomy are presented.

Results

Minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy (MIDP) is the most frequently used procedure among these, and its indications are nowadays expanding. MIDP for benign and low-grade malignant tumors is advantageous compared to the open approach, suggesting less intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospital stay, faster functional recovery, and better quality of life. The oncological adequacy of MIDP in pancreatic cancer is unclear, as no randomized trials have been published. In contrast, MIPD is a technically challenging procedure performed in a small number of centers and in a selected group of patients. Its use remains controversial, as conflicting data have been reported in the literature. Annual volume and learning curve seem to be the key determinants of safety in MIPD. Minimally invasive pancreatic enucleation and central pancreatectomy are less common. Although one randomized trial was published on minimally invasive vs. open central pancreatectomy, current evidence on these procedures is mostly based on retrospective, single-institution series clearly affected by selection bias and small sample size.

Conclusion

Well-designed prospective studies based on national registries are needed to expand knowledge on MIPS and determine its role in pancreatic surgery. To facilitate further development of MIPS, it has to integrate effectively with the outcome-improving effect of a dedicated pancreatic team.

Similar content being viewed by others

This manuscript summarizes current data and evidence level on minimally invasive pancreatic surgery. Its main types such as pancreatoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, enucleation, and central pancreatectomy are included.

Introduction

Minimally invasive pancreatic surgery (MIPS) was introduced in the mid-1990s by Gagner and co-workers, who reported laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy, enucleation, and distal pancreatectomy [1, 2]. Despite these early reports, further implementation of MIPS into clinical practice has been rather slow. Possible reasons for this are the anatomic complexity of the region, limitations of laparoscopic equipment relative to pancreatic surgery, the technically demanding nature of MIPS, and a high risk of postoperative complications.

In the early period of MIPS, minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy (MIDP) and enucleation were mostly considered in selected patients as there was no need for pancreatic anastomoses [3, 4]. The selection criteria for these procedures included tumor type, tumor size, location, involvement of adjacent tissues, and patient characteristics. In contrast, minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy (MIPD) was deemed technically challenging and associated with high perioperative risks [5]. Furthermore, its real-life benefits were largely unclear to surgeons. According to the US National Cancer Database (NCDB) review for 2010–2011, patients with lesions in the pancreatic tail were three times more likely to be operated on by MIPS than those with lesions in the pancreatic head [6]. The same study demonstrated that only 13.5% of all patients were subjected to MIPS, while 86.5% were operated on by the open approach.

The first review articles comparing MIPS and its open counterpart found comparable morbidity and mortality, although longer operative time, less blood loss, and shorter hospital stay were typical for the former [3, 5, 7, 8]. At the same time, these studies underscored the low evidence level and selection bias in the minimally invasive arm. Over the past few years, the evidence level on MIPS has somewhat increased as prospective studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and consensus articles have emerged in the literature. In this study, the current evidence on MIPS and its future perspectives are reviewed.

Minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy

The first MIDP reported by Cuschieri was performed for chronic pancreatitis in 1994 [9]. The proportion of MIDP grew exponentially over the next two decades. In the American population-based study, Tran Cao et al. found that the rate of MIDP has tripled from 2.4% of all distal pancreatectomies in 1998 to 7.3% in 2009 [10]. Data from the nationwide study in the Netherlands demonstrate a significant increase in the proportion of MIDP—from 9 to 47% [11]. In Norway, MIDP currently accounts for 59% of all distal pancreatectomies nationwide [12].

Multiple case–control studies examining outcomes of minimally invasive and open distal pancreatectomy (ODP) have been published to date. Systematic reviews of these studies report reduced intraoperative blood loss, less red blood cell transfusion, and shorter hospital stay for MIDP, but comparable incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), morbidity, and mortality [13, 14]. MIDP was also reported to be associated with relatively high spleen preservation rates compared to its open counterpart, which was explained by the magnified and enhanced visualization facilitating dissection along the splenic vessels and clear identification of small arteries and veins [15, 16]. However, this evidence is based predominantly on retrospective series affected by selection bias. Some studies even observed less postoperative complications following MIDP [7, 17]. At the same time, management of the pancreatic stump during MIDP as one of the most crucial steps of this procedure is as problematic as in open surgery, resulting in similar rates of POPF (19.1 vs. 19.9%, p = 0.73, respectively) [7]. The only RCT published to date suggests less blood loss, longer operative time, lower clinically relevant (grade B/C) delayed gastric emptying rates, shorter time to functional recovery, and better quality of life for MIDP compared with ODP [18]. Interestingly, several prospective studies focusing on costs found MIDP to be as cost effective as ODP [19,20,21].

The indications for MIDP have changed significantly over time. Although initially applied mostly for benign and low-grade malignant tumors, MIDP is becoming increasingly used for ductal adenocarcinoma. In France, its proportion in patients with cancer has doubled from 7.3% in 2007 to 14.8% in 2012 [22]. In the Netherlands, the proportion of MIDP for ductal adenocarcinoma has increased from 5 to 51% [11]. Several systematic reviews published on this topic have agreed that typical advantages of the minimally invasive technique also translate into surgery for pancreatic cancer [23, 24], but, most importantly, the long-term oncologic outcomes were comparable between MIDP and ODP [25, 26]. At the same time, MIDP was associated with less lymph node yield, smaller tumor size, and less perineural invasion, which was a result of early stage cancer and a selection bias in the minimally invasive arm.

The recent worldwide survey among pancreatic surgeons performing MIDP demonstrated that only 12% of surgeons found no contraindications for MIDP [27]. In a similar pan-European survey, 45% of surgeons claimed that they had insufficient training in MIDP for all indications [28]. The recent American nationwide study evaluating patient selection factors concluded that MIDP was more often applied in patients with benign lesions and in case of body mass index (BMI) 30–40 kg/m2, whereas ODP was a preferable option for tumors >5 cm and if multivisceral resection was needed [29]. These findings were further confirmed by the data from the NCDB, which found that pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma was independently associated with opting for the open approach [6]. Thus, questions about the oncologic adequacy and possible limits of MIDP in the setting of cancer remain unanswered. A pan-European RCT (DIPLOMA) on minimally invasive vs. open distal pancreatectomy for cancer is currently running and its results are much anticipated [30].

Laparoscopic versus robotic distal pancreatectomy

Several systematic reviews and meta-analysis have been published on laparoscopic vs. robotic distal pancreatectomy [31,32,33]. These suggest that the robotic approach is associated with longer operative time, shorter hospital stay, and higher spleen preservation rates compared with laparoscopy. However, evidence comes mostly from retrospective series. In a prospective study, Butturini et al. observed longer operative time and doubled costs for the robotic approach, but similar postoperative and oncologic outcomes [34]. Another prospective study compared robotic with laparoscopic single-site distal pancreatectomy and found longer operative time for the robotic approach, while postoperative and oncologic outcomes were similar [35]. In contrast, analysis of the US NCDB demonstrated comparable oncologic outcomes, but a higher conversion rate for laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy [36].

To date, no clear evidence-based recommendations regarding MIDP can be set, although clinical prospective series also from national quality-controlled registries are increasingly published. Clear algorithms for local development of an MIDP service should be based on a structured training program. A recent consensus study from the European association for endoscopic surgery reported a significant reduction in operative time as a learning curve parameter after 10–17 laparoscopic distal pancreatectomies [37]. Conversion rate and intraoperative blood loss were considered as possible indicators of the learning curve in MIDP.

Minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy

Since the introduction of MIPD more than 20 years ago, the attitude of surgeons towards this procedure has been controversial. First and foremost, MIPD is a highly complex procedure with a steep learning curve. Data from a high-volume center suggest decreased blood loss and conversion rate after 20 MIPDs, a decrease in pancreatic fistula after 40 procedures, and a decrease in operative time after 80 procedures [38]. At the same time, given the relatively small number of centers performing MIPD and strict patient selection criteria, its advantages over open pancreatoduodenectomy (OPD), as well as its oncologic adequacy, were unclear. According to a recent pan-European survey, only 21% of pancreatic surgeons have experience with MIPD [28]. Interestingly, 65% of responders view laparoscopy in pancreatoduodenectomy as a technical problem. The most frequently mentioned technical concern during MIPD is construction of pancreatic anastomosis [27].

During the first decade of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy in the US, the latter was performed in only 4.4% of patients referred to pancreatoduodenectomy [39]. The analysis of the NCDB from Sharpe and co-workers demonstrated that low-volume centers performing <10 laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomies annually had a twofold increase in 30-day mortality compared to OPD [40]. Another study focused on NCDB reported decreased 90-day mortality in centers performing >6 MIPD annually [41]. Thus, outcomes of MIPD seem to depend highly on the annual volume of the center.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing MIPD and OPD report less intraoperative blood loss, a lower transfusion rate, longer operative time, and shorter hospital stay for the former [42,43,44,45]. The oncologic outcomes were equivalent to those in OPD [41, 45]. However, these reports are largely based on retrospective studies affected by selection bias, and thus should be interpreted with caution. Three RCTs on MIPD vs. OPD have been published over the past few years. The first study conducted in a single institution in India demonstrated longer operative time, less blood loss, and shorter hospital stay (7 vs. 13 days, p = 0.001) for laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy compared with OPD for periampullary tumors [46]. Postoperative outcomes were comparable. This study was performed in a private hospital with a specific focus on laparoscopic surgery, with few surgeons involved and who had passed the training curve by several hundreds of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomies. This trial is therefore to be considered an expert trial. Due to an imbalance in benign to malignant cases and more pancreatic cancers in the open group, this trial will not be able to present any useful information on long-term oncological outcomes.

Another single-center RCT (PADULAP) reported less grade ≥3 postoperative complications, a lower comprehensive complication index, and shorter hospital stay for the laparoscopic approach [47]. In contrast, the Dutch multicenter randomized LEOPARD-2 trial was prematurely terminated by the safety monitoring board due to more complication-related mortality in the laparoscopic arm (10 vs. 2%) [48]. Surgeon experience, learning curve, and annual volume are thought to affect this outcome. Of note, among the patients included, there were no benefits in short-term outcomes or functional recovery in the laparoscopy group (which was the primary aim of the study).

MIPD and vascular resection

Evidence remains scarce regarding the role of MIPD in the setting of vascular resection for tumor invasion. Only a few case series from expert centers have been published on MIPD with vascular resection and reconstruction [49,50,51,52]. These mostly include venous resections and report acceptable perioperative outcomes. The only comparative study published by Croome et al. suggests comparable surgical and oncologic outcomes between MIPD with vascular resection and its open counterpart [49]. In the LEOPARD-2 trial, intraoperative vascular complications were the main cause for conversions and intraoperative complications leading to a few of the deaths that lead the trial to be stopped prematurely for safety reasons.

Laparoscopic versus robotic pancreatoduodenectomy

The review of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database found that the type of MIPD (laparoscopic or robotic) was not associated with postoperative complications [53]. Another similar study from Zimmerman et al. found that robotic surgery was less frequently performed for malignancies and was associated with more surgical site infections, but a lower conversion rate compared with laparoscopy [54]. In contrast, the recent systematic review from Ricci et al. suggests that the robotic system provided the best outcomes among minimally invasive techniques applied for pancreatoduodenectomy, while laparoscopy was associated with a high risk of postoperative complications, bleeding, and biliary leakage [55].

A recommendation for MIPD based on current evidence cannot be made due to low data quality. In view of complex reconstruction during pancreatic head resection, the robotic approach might have a greater potential.

Other minimally invasive procedures

Less frequently utilized minimally invasive procedures on the pancreas are enucleation and central pancreatectomy. Compared with pancreatoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy, these are parenchyma-sparing procedures aimed at preventing development of pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. Minimally invasive pancreatic enucleation (MIPE) has clear indications applicable also in open surgery: benign and low-grade malignant tumors with a small size ≤4 cm, and a clear distance from the main pancreatic duct.

A small number of case–control studies have been published on minimally invasive vs. open pancreatic enucleation. These report shorter operative time, less blood loss, and reduced hospital stay for the former [56,57,58,59]. A systematic review from Guerra et al. confirmed these findings, while the rates of clinically relevant POPF and major complications were similar [60]. Although initially considered for left-sided pancreatic lesions only, MIPE has also been successfully applied for tumors in the pancreatic head [59, 61]. Interestingly, both the laparoscopic and the robotic approach have been equally successful in pancreatic enucleation, as reported in the aforementioned studies. At the same time, strict patient selection criteria and a lack of randomized trials on this topic limit current knowledge on the role of MIPE.

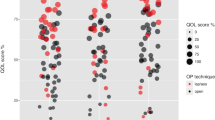

Minimally invasive central pancreatectomy (MICP) is normally applied for benign or low-grade malignant lesions like small neuroendocrine neoplasms located in the pancreatic body and neck, which cannot be removed by MIPE due to tumor proximity to the main pancreatic duct. At the same time, this procedure bears risks and challenges, such as technically demanding pancreatic anastomosis and two potential sources of POPF. Only small case series had been published on MICP until recently [62, 63]. One of the first comparative studies between minimally invasive and open central pancreatectomy conducted by Song et al. demonstrated longer operative time but shorter hospital stay for MICP [64]. Another similar report from Asia suggests less blood loss as well as shorter first flatus and diet start times following laparoscopic central pancreatectomy [65]. Quality of life parameters were higher for laparoscopy compared to the open approach yet without statistical significance. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Xiao and co-workers demonstrated similar POPF rates, morbidity, and incidence of postoperative exocrine and endocrine insufficiency between minimally invasive and open central pancreatectomy [66]. However, the reoperation rate was higher for MICP. Interestingly, the use of pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreaticogastrostomy was almost equal during MICP, while POPF rates between them were similar. Finally, an RCT on robot-assisted laparoscopic vs. open central pancreatectomy published by Chen et al. suggests shorter operative time, less blood loss, lower incidence of clinically relevant POPF, and faster postoperative recovery after laparoscopy [67]. The long-term data on MICP from this trial are awaited.

Future perspectives

More than two decades have passed since the introduction of MIPS and five RCTs have been published to date (Table 1). Yet implementation of MIPS has advanced differently for pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy. If the progress of MIDP over the past two decades and its perspectives are obvious, the future of MIPD is unclear. MIDP is currently gaining widespread acceptance among pancreatic surgeons worldwide and will likely soon replace its open counterpart. The main question yet to be answered regarding MIDP is whether it is as oncologically effective and safe as the open approach. Hopefully, the ongoing DIPLOMA trial on minimally invasive vs. open distal pancreatectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma will give all answers and allow for the extension of boundaries for MIDP and its full recognition. Furthermore, the learning curve and implementation of MIDP into clinical practice is rather straightforward and technically feasible. Thus, it has a good chance of becoming the “gold standard” in the near future.

The situation is rather different with MIPD. The rationale for its use remains controversial. Although some studies report typical advantages of the minimally invasive approach also for MIPD, high mortality observed in a number of population-based studies and in the recent Dutch RCT warrants further investigation. This problem was shown to be associated with low-volume centers performing MIPD. Hence, one possible solution could be centralizing the health care system and concentrating MIPD in high-volume centers with a sufficient level of expertise, where the benefits of MIPD can be perceived. All in all, more evidence is needed to clarify the utility of MIPD.

MIPE and MICP are limited to a small number of selected patients. However, these procedures merit further scrutiny, as they bear significant advantages over formal resections in terms of preserving pancreatic gland function and improving patients’ quality of life. Well-designed multicenter RCTs are needed to proceed with the assessment of MIPE and MICP.

The first consensus expert meeting on MIDP and MIPD is awaited in March 2019, presumably leading to evidence-based recommendations regarding the routine implementation of minimally invasive surgery for pancreatic disease.

In conclusion, although the outcomes both for minimally invasive and open pancreatic surgery are dependent on the technical skills of the single surgeon, the optimal clinical environment and a dedicated pancreatic team plays a greater role in managing patient selection, safe surgery, and overcoming postoperative complications [68]. To facilitate further development of MIPS, it has to integrate effectively with the outcome-improving effect of a dedicated pancreatic team.

References

Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8(5):408–10.

Gagner M, Pomp A, Herrera MF. Early experience with laparoscopic resections of islet cell tumors. Surgery. 1996;120(6):1051–4.

Al-Taan OS, Stephenson JA, Briggs C, Pollard C, Metcalfe MS, Dennison AR. Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: a review of present results and future prospects. HPB. 2010;12(4):239–43.

Iihara M, Obara T. Recent advances in minimally invasive pancreatic surgery. Asian J Surg. 2003;26(2):86–91.

Briggs CD, Mann CD, Irving GR, Neal CP, Peterson M, Cameron IC, et al. Systematic review of minimally invasive pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(6):1129–37.

Gabriel E, Thirunavukarasu P, Attwood K, Nurkin SJ. National disparities in minimally invasive surgery for pancreatic tumors. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(1):398–409.

Venkat R, Edil BH, Schulick RD, Lidor AO, Makary MA, Wolfgang CL. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is associated with significantly less overall morbidity compared to the open technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;255(6):1048–59.

Correa-Gallego C, Dinkelspiel HE, Sulimanoff I, Fisher S, Vinuela EF, Kingham TP, et al. Minimally-invasive vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(1):129–39.

Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1994;39(3):178–84.

Cao THS, Lopez N, Chang DC, Lowy AM, Bouvet M, Baumgartner JM, et al. Improved perioperative outcomes with minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy: results from a population-based analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(3):237–43.

de Rooij T, van Hilst J, Boerma D, Bonsing BA, Daams F, van Dam RM, et al. Impact of a nationwide training program in minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy (LAELAPS). Ann Surg. 2016;264(5):754–762.

Soreide K, Olsen F, Nymo LS, Kleive D, Lassen K. A nationwide cohort study of resection rates and short-term outcomes in open and laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. HPB. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2018.10.006

Mehrabi A, Hafezi M, Arvin J, Esmaeilzadeh M, Garoussi C, Emami G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy for benign and malignant lesions of the pancreas: It’s time to randomize. Surgery. 2015;157(1):45–55.

Jin T, Altaf K, Xiong JJ, Huang W, Javed MA, Mai G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. HPB. 2012;14(11):711–24.

Fernandez-Cruz L, Saenz A, Astudillo E, Martinez I, Hoyos S, Pantoja JP, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: endocrine and nonendocrine tumors. World J Surg. 2002;26(8):1057–65.

Park AE, Heniford BT. Therapeutic laparoscopy of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2002;236(2):149–58.

Yi X, Chen S, Wang W, Zou L, Diao D, Zheng Y, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy of Nonductal Adenocarcinomatous Pancreatic Tumor (NDACPT) in the pancreatic body and tail. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutaneous Tech. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLE.0000000000000416.

de Rooij T, van Hilst J, van Santvoort H, Boerma D, van den Boezem P, Daams F, et al. Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy (LEOPARD): a multicenter patient-blinded randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002979.

Xourafas D, Tavakkoli A, Clancy TE, Ashley SW. Distal pancreatic resection for neuroendocrine tumors: Is laparoscopic really better than open? J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(5):831–40.

Braga M, Pecorelli N, Ferrari D, Balzano G, Zuliani W, Castoldi R. Results of 100 consecutive laparoscopic distal pancreatectomies: postoperative outcome, cost-benefit analysis, and quality of life assessment. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(7):1871–8.

Ricci C, Casadei R, Taffurelli G, Bogoni S, D’Ambra M, Ingaldi C, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy in benign or premalignant pancreatic lesions: Is it really more cost-effective than open approach? J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(8):1415–24.

Sulpice L, Farges O, Goutte N, Bendersky N, Dokmak S, Sauvanet A, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Time for a randomized controlled trial? Results of an all-inclusive national observational study. Ann Surg. 2015;262(5):868–74.

Ricci C, Casadei R, Taffurelli G, Toscano F, Pacilio CA, Bogoni S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(4):770–81.

Chen K, Pan Y, Zhang B, Maher H, Cai XJ. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;53:243–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.12.032

Huang SF, Chien TH, Fang WL, Wang F, Tsai CY, Hsu JT, et al. The 8th edition American Joint Committee on gastric cancer pathological staging classification performs well in a population with high proportion of locally advanced disease. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.05.036.

van Hilst J, Korrel M, de Rooij T, Lof S, Busch OR, Groot Koerkamp B, et al. Oncologic outcomes of minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.12.003.

van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Abu Hilal M, Asbun HJ, Barkun J, Boggi U, et al. Worldwide survey on opinions and use of minimally invasive pancreatic resection. HPB. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2017.01.011.

de Rooij T, Besselink MG, Shamali A, Butturini G, Busch OR, Edwin B, et al. Pan-European survey on the implementation of minimally invasive pancreatic surgery with emphasis on cancer. HPB. 2016;18(2):170–6.

Klompmaker S, van Zoggel D, Watkins AA, Eskander MF, Tseng JF, Besselink MG, et al. Nationwide evaluation of patient selection for minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy using American College of Surgeons’ national quality improvement program. Ann Surg. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001982.

Hilal MA. Distal pancreatectomy, minimally invasive or open, for malignancy. https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN44897265

Zhou JY, Xin C, Mou YP, Xu XW, Zhang MZ, Zhou YC, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis of short-term outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e151189.

Huang B, Feng L, Zhao J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of robotic versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy for benign and malignant pancreatic lesions. Surg Endosc. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4723-7.

Niu X, Yu B, Yao L, Tian J, Guo T, Ma S, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes of robot-assisted laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy versus laparoscopic and open resections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Surg. 2019;42(1):32–45.

Butturini G, Damoli I, Crepaz L, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Daskalaki D, et al. A prospective non-randomised single-center study comparing laparoscopic and robotic distal pancreatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(11):3163–70.

Ryan CE, Ross SB, Sukharamwala PB, Sadowitz BD, Wood TW, Rosemurgy AS. Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy: a robotic or LESS approach. JSLS. 2015;19(1):e2014.00246.

Raoof M, Nota C, Melstrom LG, Warner SG, Woo Y, Singh G, et al. Oncologic outcomes after robot-assisted versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: Analysis of the National Cancer Database. J Surg Oncol. 2018;118(4):651–6.

Edwin B, Sahakyan MA, Hilal MA, Besselink MG, Braga M, Fabre JM, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for pancreatic neoplasms: the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery clinical consensus conference. Surg Endosc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5414-3.

Boone BA, Zenati M, Hogg ME, Steve J, Moser AJ, Bartlett DL, et al. Assessment of quality outcomes for robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy: identification of the learning curve. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(5):416–22.

Tran TB, Dua MM, Worhunsky DJ, Poultsides GA, Norton JA, Visser BC. The first decade of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in the United States: costs and outcomes using the nationwide inpatient sample. Surg Endosc. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4444-y.

Sharpe SM, Talamonti MS, Wang CE, Prinz RA, Roggin KK, Bentrem DJ, et al. Early national experience with laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma: a comparison of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy and open pancreaticoduodenectomy from the National Cancer Data Base. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(1):175–84.

Torphy RJ, Friedman C, Halpern A, Chapman BC, Ahrendt SS, McCarter MM, et al. Comparing short-term and oncologic outcomes of minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy across low and high volume centers. Ann Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002810.

Qin H, Qiu J, Zhao Y, Pan G, Zeng Y. Does minimally-invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy have advantages over its open method? A meta-analysis of retrospective studies. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e104274.

de Rooij T, Lu MZ, Steen MW, Gerhards MF, Dijkgraaf MG, Busch OR, et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative cohort and registry studies. Ann Surg. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001660

Zhang H, Wu X, Zhu F, Shen M, Tian R, Shi C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of minimally invasive versus open approach for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(12):5173–5184.

Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Wang B, Xu Y, Du W. Minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: an up-to-date meta-analysis of comparative cohort studies. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech Part A. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2018.0460

Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, Babu NS, Srivatsan Gurumurthy S, Anand Vijai N, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 2017;104(11):1443–50.

Poves I, Burdio F, Morato O, Iglesias M, Radosevic A, Ilzarbe L, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and open approach for pancreatoduodenectomy: the PADULAP randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268(5):731–9.

van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, Brinkman DJ, van Dieren S, Dijkgraaf MG, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30004-4.

Croome KP, Farnell MB, Que FG, Reid-Lombardo KM, Truty MJ, Nagorney DM, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with major vascular resection: a comparison of laparoscopic versus open approaches. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(1):189–94. discussion 194.

Khatkov IE, Izrailov RE, Khisamov AA, Tyutyunnik PS, Fingerhut A. Superior mesenteric-portal vein resection during laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5115-3.

Cai Y, Gao P, Li Y, Wang X, Peng B. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy with major venous resection and reconstruction: anterior superior mesenteric artery first approach. Surg Endosc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6167-3.

Wang X, Cai Y, Zhao W, Gao P, Li Y, Liu X, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy combined with portal-superior mesenteric vein resection and reconstruction with interposition graft: case series. Medicine. 2019;98(3):e14204.

Nassour I, Wang SC, Porembka MR, Yopp AC, Choti MA, Augustine MM, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a NSQIP analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(11):1784–92.

Zimmerman AM, Roye DG, Charpentier KP. A comparison of outcomes between open, laparoscopic and robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB. 2018;20(4):364–9.

Ricci C, Casadei R, Taffurelli G, Pacilio CA, Ricciardiello M, Minni F. Minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: What is the best “choice”? A systematic review and network meta-analysis of non-randomized comparative studies. World J Surg. 2018;42(3):788–805.

Zhang RC, Zhou YC, Mou YP, Huang CJ, Jin WW, Yan JF, et al. Laparoscopic versus open enucleation for pancreatic neoplasms: clinical outcomes and pancreatic function analysis. Surg Endosc. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4538-6.

Song KB, Kim SC, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Lee DJ, Lee JW, et al. Enucleation for benign or low-grade malignant lesions of the pancreas: single-center experience with 65 consecutive patients. Surgery. 2015;158(5):1203–10.

Tian F, Hong XF, Wu WM, Han XL, Wang MY, Cong L, et al. Propensity score-matched analysis of robotic versus open surgical enucleation for small pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Br J Surg. 2016;103(10):1358–64.

Jin JB, Qin K, Li H, Wu ZC, Zhan Q, Deng XX, et al. Robotic enucleation for benign or borderline tumours of the pancreas: a retrospective analysis and comparison from a high-volume centre in Asia. World J Surg. 2016;40(12):3009–20.

Guerra F, Giuliani G, Bencini L, Bianchi PP, Coratti A. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatic enucleation. Systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. J Surg Oncol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.25026.

Sahakyan MA, Rosok BI, Kazaryan AM, Barkhatov L, Haugvik SP, Fretland AA, et al. Role of laparoscopic enucleation in the treatment of pancreatic lesions: case series and case-matched analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5233-y.

Hamad A, Novak S, Hogg ME. Robotic central pancreatectomy. J Visc Surg. 2017;3:94.

Machado MA, Surjan RC, Epstein MG, Makdissi FF. Laparoscopic central pancreatectomy: a review of 51 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutaneous Tech. 2013;23(6):486–90.

Song KB, Kim SC, Park KM, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Lee DJ, et al. Laparoscopic central pancreatectomy for benign or low-grade malignant lesions in the pancreatic neck and proximal body. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(4):937–46.

Zhang RC, Zhang B, Mou YP, Xu XW, Zhou YC, Huang CJ, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes and quality of life between laparoscopic and open central pancreatectomy with pancreaticojejunostomy. Surg Endosc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5552-7.

Xiao W, Zhu J, Peng L, Hong L, Sun G, Li Y. The role of central pancreatectomy in pancreatic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB. 2018;20(10):896–904.

Chen S, Zhan Q, Jin JB, Wu ZC, Shi Y, Cheng DF, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic versus open middle pancreatectomy: short-term results of a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(2):962–71.

Bassi C, Andrianello S. Identifying key outcome metrics in pancreatic surgery, and how to optimally achieve them. HPB. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2016.12.002.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M.A. Sahakyan, K.J. Labori, F. Primavesi, K. Søreide, S. Stättner, and B. Edwin declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahakyan, M.A., Labori, K.J., Primavesi, F. et al. Minimally invasive pancreatic surgery—where are we going?. Eur Surg 51, 98–104 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-019-0576-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-019-0576-y