Abstract

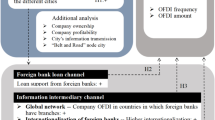

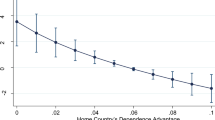

We argue that competitive diffusion is a driver of the trend toward international investment agreements with stricter investment rules, namely defensive moves of developing countries concerned about foreign direct investment (FDI) diversion in favor of competing host countries. Accounting for spatial dependence in the formation of bilateral investment treaties and preferential trade agreements that contain investment provisions, we find that the increase in agreements with stricter provisions on investor-to-state dispute settlement and pre-establishment national treatment is a contagious process. Specifically, a developing country is more likely to sign an agreement with weak investment provisions if other developing countries that compete for FDI from the same developed country have previously signed agreements with similarly weak provisions. Conversely, contagion in agreements with strong provisions exclusively derives from agreements with strong provisions that other FDI-competing developing countries have previously signed with a specific developed source country of FDI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the term “developing countries” as short cut for all countries that are not one of the developed FDI source countries listed in “Appendix 1”. It therefore also includes countries often called countries in transition.

Baldwin and Jaimovich (2012) show that, in contrast to custom unions, the gains from signing a free trade agreement with a given partner country are decreasing in the number of free trade agreements the partner country already has.

Various indicators are considered to define the depth of each of the key characteristics. For instance, investment agreements may contain provisions on expropriation, transfers, minimum standard of treatment, most-favored-nation treatment, as well as non-discrimination for pre- and post-establishment operations.

Note that a k-ad stands for a group of states with size k consisting of one source country and a varying number of host countries, including dyads with just one host country.

By contrast, other types of contagion appear to have negative effects on the process of BIT formation.

By restricting our analysis to BITs and PTAs we may miss a very small number of IIAs that come neither in the form of BITs nor PTAs.

However, some recent IIAs do not include (strict) ISDS provisions, e.g., IIAs involving the European Union.

The total number of known cases exceeded 500 in 2012. For details, see: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webdiaepcb2013d3_en.pdf (Accessed January 2014).

However, obligations on market access are a standard feature of BITs concluded by the United States and Canada.

This estimation technique produces almost identical results as a conditional logit estimator with period fixed effects (Beck et al. 1998).

Our definition of independence is either full political independence or being independent in the sense of having signed international treaties like double taxation treaties (see Barthel and Neumayer 2012).

See “Appendix 5” for details.

Note that we decompose the PTA-related control variable in the same way.

The results for the control variables are similar to the estimations reported in Table 1 (detailed results not reported). Of note, however, the bargaining perspective now receives some support when the dependent variable refers to BITs with strong ISDS provisions by the fact that a larger difference in total economic size between the source and host country now significantly increases the hazard of signing BITs with strong ISDS provisions. Richer host countries are also more likely to sign these types of treaties.

Namely, the two PTAs between the countries of the European Free Trade Area (Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, Liechtenstein) and Mexico and Chile, respectively; the PTA between the EU-15 countries and Mexico as well as EU enlargement agreements involving countries that in our sample are classified as developing host countries.

Results on the control variables are similar to the ones reported in Table 2, except that larger distance now continues to deter BITs/PTAs with strong ISDS/NT provisions and weak (strong) ISDS/NT provisions become more (less) likely the richer the FDI source country.

In addition, restricting the source country sample to the top 6 FDI sources mitigates the problem of potentially unreported bilateral FDI stocks and, thus, reduces the number of FDI observations set to zero (see “Appendix 5” for details).

We consequently exclude the plurilateral PTA among members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Distinguishing between the top 6 FDI source countries and other source countries, the pattern of export-weighted specific source contagion essentially holds for both groups of source countries (results not shown). In particular, the evidence for specific source contagion continues to be stronger than for the benchmark results with FDI-weighted spatial lags.

This implies that our sample can only start in 1987, instead of 1978, in this robustness test. We truncate to zero in case this value is negative, which happens in 0.56 % of cases.

As discussed in more detail in “Appendix 5”, the impact of older FDI stocks is already reduced to the extent that reporting countries adhere to internationally agreed best practices of accounting for accumulated depreciation to arrive at net property, plant and equipment values.

References

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2010). Delegating differences: Bilateral investment treaties and bargaining over dispute resolution provisions. International Studies Quarterly, 54(1), 1–26.

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2011). Contingent credibility: The reputational effects of investment treaty disputes on foreign direct investment. International Organization, 65(3), 1–26.

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2014). Evaluating three explanations for the design of bilateral investment treaties. World Politics, 66(1), 47–87.

Baccini, L., & Dür, A. (2012). The new regionalism and policy interdependence. British Journal of Political Science, 42(1), 57–79.

Baldwin, R. (1993). A domino theory of regionalism. (NBER Working Paper 4465). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Baldwin, R. (1997). The causes of regionalism. World Economy, 20(7), 865–888.

Baldwin, R., & Jaimovich, D. (2012). Are free trade agreements contagious? Journal of International Economics, 88(1), 1–16.

Barthel, F., Busse, M., & Neumayer, E. (2010). The impact of double taxation treaties on foreign direct investment: Evidence from large dyadic panel data. Contemporary Economic Policy, 28(3), 366–377.

Barthel, F., & Neumayer, E. (2012). Competing for scarce foreign capital: Spatial dependence in the diffusion of double taxation treaties. International Studies Quarterly, 56(4), 645–660.

Beck, N., Katz, J. N., & Tucker, R. (1998). Taking time seriously: Time-series-cross-section analysis with a binary dependent variable. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 1260–1288.

Berger, A., Busse, M., Nunnenkamp, P., & Roy, M. (2011). More stringent BITs, less ambiguous effects on FDI? Not a bit! Economics Letters, 112(3), 270–272.

Berger, A., Busse, M., Nunnenkamp, P., & Roy, M. (2013). Do trade and investment agreements lead to more FDI? Accounting of key provisions inside the black box. International Economics and Economic Policy, 10(2), 247–275.

Bergstrand, J. H., & Egger, P. (2013). What determines BITs? Journal of International Economics, 90(1), 107–122.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. V. (2014). Foreign direct investment and institutional diversity in trade agreements: Credibility, commitment, and economic flows in the developing world, 1971–2007. World Politics, 66(1), 88–122.

Cameron, C., Gelbach, J., & Miller, D. (2011). Robust inference with multiway clustering. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 29(2), 238–249.

Cleves, M., Gutierrez, R. G., Gould, W., & Marchenko, Y. V. (2010). An introduction to survival analysis using stata (3rd ed.). College Station: Stata Press.

Dür, A., Baccini, L., & Elsig, M. (2014). The design of international trade agreements: Introducing a new dataset. Review of International Organizations, 9(3), 353–375.

Elkins, Z., Guzman, A. T., & Simmons, B. A. (2006). Competing for capital: The diffusion of bilateral investment treaties, 1960–2000. International Organization, 60(4), 811–846.

Guzman, A. T. (1997). Why LDCs sign treaties that hurt them: Explaining the popularity of bilateral investment treaties. Virginia Journal of International Law, 38, 639–688.

Henderson, D. (1999). The MAI affair: A story and its lessons. London: Royal Institute of International Affairs.

Hoekman, B., & Newfarmer, R. (2005). Preferential trade agreements, investment disciplines and investment flows. Journal of World Trade, 39(5), 949–973.

IMF (2003). Foreign direct investment statistics: How countries measure FDI, 2001. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IMF (2013). Sixth edition of the IMF’s balance of payments and international investment position manual (BPM6). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bop/2007/bopman6.htm).

IMF (2014). Balance of payments and international investment position compilation guide. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bop/2007/bop6comp.htm).

Jandhyala, S., Henisz, W. J., & Mansfield, E. D. (2011). Three waves of BITs: The global diffusion of foreign investment policy. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(6), 1047–1073.

Kerner, A. (2009). Why should I believe you? The costs and consequences of bilateral investment treaties. International Studies Quarterly, 53(1), 73–102.

Koremenos, B. (2007). If only half of international agreements have dispute resolution provisions, which half needs explaining? Journal of Legal Studies, 36, 189–212.

Lipsey, R. E. (2001). Foreign direct investment and the operations of multinational firms: Concepts, history, and data. (NBER Working Paper 8665). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lupu, Y., & Poast, P. (2013). Are bilateral investment treaties really bilateral? Mimeo. Available at: https://ncgg.princeton.edu/IPES/2013/papers/F900_rm2.pdf. Accessed Jan 2014.

Mansfield, E., & Milner, H. (2012). Votes, vetoes, and the political economy of international trade agreements. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mansfield, E., Milner, H., & Pevehouse, J. (2008). Democracy, veto players and the depth of regional integration. World Economy, 31(1), 67–96.

Milner, H. (2014). Introduction: The global economy, FDI, and the regime for investment. World Politics, 66(1), 1–11.

Neumayer, E., & Plümper, T. (2010). Spatial effects in dyadic data. International Organization, 64(1), 145–166.

OECD (2006). Novel features in recent OECD bilateral investment treaties. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

OECD (2008). OECD benchmark definition of foreign direct investment (4th ed.). Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Poulsen, L. S., & Aisbett, E. (2013). When the claim hits: Bilateral investment treaties and bounded rational learning. World Politics, 65(2), 273–313.

Roy, M. (2011). Democracy and the political economy of multilateral commitments on trade in services. Journal of World Trade, 45(6), 1157–1180.

Sachs, L. E., & Sauvant, K. P. (2009). BITs, DTTs, and FDI flows: An overview. In K. P. Sauvant & L. E. Sachs (Eds.), The effect of treaties on foreign direct investment: Bilateral investment treaties, double taxation treaties, and investment flows (pp. 28–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Salacuse, J. W. (2010). The emerging global regime for investment. Harvard International Law Journal, 51(2), 427–473.

Sauvant, K. P., & Sachs, L. E. (Eds.). (2009). The effect of treaties on foreign direct investment: Bilateral investment treaties, double taxation treaties, and investment flows. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simmons, B. A. (2014). Bargaining over BITs, arbitrating awards: The regime for protection and promotion of international investment. World Politics, 66(1), 12–46.

Swenson, D. L. (2005). Why do developing countries sign BITs? U.C. Davis Journal of International Law and Policy, 12(1), 131–155.

Tobin, J., & Busch, M. L. (2010). A BIT is better than a lot: Bilateral investment treaties and preferential trade agreements. World Politics, 62(1), 1–41.

Tobin, J., & Rose-Ackerman, S. (2011). When BITs have some bite: The political-economic environment for bilateral investment treaties. Review of International Organizations, 6(1), 1–31.

UNCTAD (2009). Training manual on statistics for FDI and the operations of TNCs, Vol 1: FDI flows and stocks. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD (2013). World investment report 2013. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

Yackee, J. (2009). Do BITS really work? Revisiting the empirical link between investment treaties and foreign direct investment. In K. P. Sauvant & L. E. Sachs (Eds.), The effect of treaties on foreign direct investment: Bilateral investment treaties, double taxation treaties, and investment flows (pp. 379–394). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 10.

Appendix 2: List of host countries of FDI in sample

Albania, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo (Republic), Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Latvia, Lithuania, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Oman, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Seychelles, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sri Lanka, South Korea, Sudan, Swaziland, Syrian Arab Republic, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Uruguay, Venezuela, Vietnam, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Appendix 3

See Table 11.

Appendix 4

See Table 12.

Appendix 5: FDI data issues

5.1 “Missing” FDI

The IMF’s Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Compilation Guide (IMF 2014), the OECD’s Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct Investment (OECD 2008) and UNCTAD’s Training Manual on Statistics for FDI and the Operations of TNCs (UNCTAD 2009) all provide detailed instructions on how to compile FDI statistics and specify the involved complexities in voluminous manuals with hundreds of pages. Nevertheless, the reliability of actually available FDI data suffers from several shortcomings.

The instructions on international best practices have not only been revised repeatedly, but various developing countries can safely be assumed to lack the administrative expertise and capacity to follow the detailed instructions. As a matter of fact, even more developed countries differ in the degree to which they adhere to current best practices as given by the above mentioned institutions (IMF 2003).

All the same, we see good reasons to prefer bilateral FDI stocks as weights in the construction of spatial lag variables when assessing host-country competition for FDI through international agreements. First of all, the fact that both UNCTAD and the OECD report bilateral FDI statistics covering our large sample can be taken as the first indication that these institutions are confident to convey relevant, though inaccurate information by making these statistics available. Second, we tentatively assessed whether the magnitude of “missing FDI” is considerably larger than “missing trade,” which could be expected if FDI reporting was seriously deficient. Specifically, we compared the difference between (worldwide) outward FDI stocks declared by source countries and (worldwide) inward FDI stocks declared by host countries with the difference between worldwide exports and worldwide imports (details not shown here, but available on request). It is well known that world imports typically exceed world exports by about 2–5 %. The gap between inward and outward FDI stocks was much larger during the earlier part of our period of observation (about 20 % in the first half of the 1980s). However, the underreporting of outward FDI in these years is unlikely to affect our estimations since we refer to inward FDI stocks whenever available. Subsequently, the FDI gap continues to be larger than the trade gap (2–10 %, compared to 2–5 %); but “missing FDI” does not appear to be excessive compared to “missing trade”. See also Lipsey (2001: 27) who noted: “The worldwide discrepancy between outward and inward direct investment flows, which should be zero if all flows were recorded fully and consistently by both sides, has been no higher than 8 % in any year from 1993 to 1999, as contrasted with 40 or 50 % for portfolio investment.”

It is also noteworthy in this context that Barthel et al. (2010) find a fairly high correlation between inward and outward FDI stocks for those dyads in the FDI database which is also underlying our analysis with both the host and the source country reporting the relevant (inward and outward) FDI data (r = 0.86).

5.2 Valuing historical FDI stocks

As noted above, the adherence to best practices in reporting FDI stocks differs across countries and also has changed over time. Current IMF-OECD-UNCTAD guidelines recommend market values prevailing at the time of compilation as the basis for valuing FDI stocks. In practice, book values from the balance sheets of enterprises are often used as proxies of the market value of FDI stocks (for details, see IMF 2003: Sect. 7). If based on historical costs, such balance sheet values do not conform to the preferred market-price principle.

Importantly, using FDI stocks at historical costs does not necessarily imply that old FDI stocks would be weighted equally as most recently built FDI stocks in our calculation of spatial lags. For instance, the valuation of the direct investment position in US economic accounts, as specified by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, explicitly accounts for accumulated depreciation to arrive at net property, plant and equipment at historical cost (for details, see: https://ideas.repec.org/p/bea/papers/0025.html). The IMF’s Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Compilation Guide (https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bop/2007/bop6comp.htm) lists Own Funds at Book Value (OFBV) as one of six methods for approximating market value for unlisted equity: “OFBV involves valuing a company at the value appearing in its books following International Accounting Standards (IAS). (…) IAS require most financial assets to be revalued on, at least, an annual basis and for plant and equipment to be depreciated” (IMF 2014: Appendix 4, paragraph A4.48).

It remains open to question, however, how many developing countries fail to meet demanding international standards on reporting FDI stocks. As noted by the IMF (2013: 123), “in cases in which none of the above methods are feasible, less suitable data may need to be used as data inputs. For example, cumulated flows or a previous balance sheet adjusted by subsequent flows may be the only sources available.” UNCTAD notes: “For a large number of economies, FDI stocks are estimates by either cumulating FDI flows over a period of time or adding flows to an FDI stock that has been obtained for a particular year from national official sources” (http://unctad.org/en/Pages/DIAE/Investment%20and%20Enterprise/FDI_Stocks.aspx). Hence, we perform an additional robustness test by subtracting from any year’s FDI stock the value of FDI stocks from 10 years prior (see main text for details).

5.3 Zero observations

In a dyadic setting, annual FDI data are frequently zero. What is more, it is often hard to decide whether zero observations are ‘real’ in the sense that partner countries explicitly report zero flows and/or stocks. In various instances, it cannot be ruled out that zero observations result from incomplete reporting (‘fake’ zeros).

It is in several ways that we reduce the risk of ‘fake’ zeros in our analysis. First of all, we use FDI stocks, rather than FDI flows, and we take averages over 3 years. The frequency of zeros, and thus the risk of ‘fake’ zeros, is considerably lower for FDI stocks than for FDI flows—particularly when considering period averages, rather than annual data. The risk of ‘fake’ zeros is further reduced in our analysis, compared to previous dyadic analyses. We consider developing countries only as hosts of FDI, not as sources of FDI. In other words, our analysis excludes dyads comprising two developing countries. Misreporting is most likely for these excluded dyads.

Furthermore, the preferred use of inward FDI in our analysis minimizes the risk that ‘fake’ zeros result in seriously biased spatial weights. Typically, missing entries in the reporting of FDI by host countries are less likely for more important sources of their inward FDI. Hence, it is unlikely that the two FDI terms in our formula for specific target contagion become zero because of incomplete reporting as long as the source country i is important enough for host country j and, respectively, competing host countries m. On the other hand, if one of the FDI terms in this formula is zero because of incomplete reporting, this does not cause serious bias as the missing source country i is most likely to be unimportant for host country j and/or competing host countries m. In other words, ‘fake’ zeros are unlikely to result in biased FDI-related weights unless decision makers have better information on the importance of specific source countries and competing host countries, compared to the researcher relying on official statistics.

About this article

Cite this article

Neumayer, E., Nunnenkamp, P. & Roy, M. Are stricter investment rules contagious? Host country competition for foreign direct investment through international agreements. Rev World Econ 152, 177–213 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-015-0231-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-015-0231-z

Keywords

- Bilateral investment treaties

- Preferential trade agreements

- Investment provisions

- Competition for FDI

- Spatial dependence