Abstract

Cirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C should be monitored for the evaluation of liver function and screening of hepatocellular carcinoma even after sustained virological response (SVR). The stage of inflammatory resolution and regression of fibrosis is likely to happen, once treatment and viral clearance are achieved. However, liver examinations by elastography show that 30–40% of patients do not exhibit a reduction of liver stiffness. This work was a cohort study in cirrhotic patients whose purpose was to identify immunological factors involved in the regression of liver stiffness in chronic hepatitis C and characterize possible serum biomarkers with prognostic value. The sample universe consisted of 31 cirrhotic patients who underwent leukocyte immunophenotyping, quantification of cytokines/chemokines and metalloproteinase inhibitors in the pretreatment (M1) and in the evaluation of SVR (M2). After exclusion criteria application, 16 patients included were once more evaluated in M3 (like M1) and classified into regressors (R) or non-regressors (NR), decrease or not ≥ 25% stiffness, respectively. The results from ROC curve, machine learning (ML) and linear discriminant analysis showed that TCD4 + lymphocytes (absolute) are the most important biomarkers for the prediction of the regression (AUC = 0.90). NR patients presented levels less than R of liver stiffness since baseline, whereas NK cells were increased in NR. Therefore, it was concluded that there is a difference in the profile of circulating immune cells in R and NR, thus allowing the development of a predictive model of regression of liver stiffness after SVR. These findings should be validated in greater numbers of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Eisenhardt M, Glässner A, Krämer B, et al. The CXCR3(+)CD56Bright phenotype characterizes a distinct NK cell subset with anti-fibrotic potential that shows dys-regulated activity in hepatitis C. Sandberg JK, editor. PLoS ONE. 2012;7: e38846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038846

Anjo J, Café A, Carvalho A, et al. O impacto da hepatite C em Portugal. GE J Port Gastrenterol. 2014;21:44–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpg.2014.03.001.

Knop V, Hoppe D, Welzel T, et al. Regression of fibrosis and portal hypertension in HCV-associated cirrhosis and sustained virologic response after interferon-free antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:994–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12578.

Baskic D, Vukovic V, Popovic S, et al. Correction: chronic hepatitis C: conspectus of immunological events in the course of fibrosis evolution (PLoS ONE (2019)14:7 (e0219508). doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219508). PLoS ONE. 2019;14: 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221142

Irshad M, Gupta P, Irshad K. Immunopathogenesis of liver injury during hepatitis C Virus infection. Viral Immunol. 2019;32:112–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/vim.2018.0124.

Grotto RMT, Santos FM, Picelli N, et al. HPA-1a/1b could be considered a molecular predictor of poor prognosis in chronic hepatitis C. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;52:2. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0427-2017.

Saha B, Szabo G. Innate immune cell networking in hepatitis C virus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;96:757–66. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.4mr0314-141r.

Patra T, Ray R, Ray R. Strategies to circumvent host innate immune response by hepatitis C virus. Cells. 2019;8:274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8030274.

Schuppan D, Kim YO. Review series: evolving therapies for liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1887–901. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI66028.Fibrosis.

Alhetheel A, Albarrag A, Shakoor Z, Alswat K, Abdo A, Al-Hamoudi W. Assessment of proinflammatory cytokines in sera of patients with hepatitis C virus infection before and after anti-viral therapy. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016;10:1093–8. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.7595.

Campana L, Iredale J. Regression of liver fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2017;37:001–10. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1597816.

Aydin MM, Akcali KC. Liver fibrosis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:14–21. https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2018.17330.

Rockey DC. Translating an understanding of the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis to novel therapies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:224–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.005.

Quarleri JF, Oubiña JR. Hepatitis c virus strategies to evade the specific-T cell response: a possible mission favoring its persistence. Ann Hepatol. 2016;15:17–26. https://doi.org/10.5604/16652681.1184193.

Cosmi L, Maggi L, Santarlasci V, Liotta F, Annunziato F. T helper cells plasticity in inflammation. Cytom Part A. 2014;85:36–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.a.22348.

Barathan M, Mohamed R, Yong Y, Kannan M, Vadivelu J, Saeidi A, et al. Viral persistence and chronicity in hepatitis C virus infection: Role of T-cell apoptosis. Senescence Exhaust Cells. 2018;7:165. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells7100165.

Poznanski SM, Barra NG, Ashkar AA, Schertzer JD. Immunometabolism of T cells and NK cells: metabolic control of effector and regulatory function. Inflamm Res. 2018;67:813–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-018-1174-3.

Terai S, Tsuchiya A. Status of and candidates for cell therapy in liver cirrhosis: overcoming the “point of no return” in advanced liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:129–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-016-1258-1.

Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, Trepo C, Lindsay K, Goodman Z, et al. Impact of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1303–13. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.33023.

Castera L. Invasive and non-invasive methods for the assessment of fibrosis and disease progression in chronic liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:291–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2011.02.003.

Patel K, Remlinger KS, Walker TG, et al. Multiplex protein analysis to determine fibrosis stage and progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(2113–2120):e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.037.

Fernandes FF, Piedade J, Guimaraes L, et al. Effectiveness of direct-acting agents for hepatitis C and liver stiffness changing after sustained virological response. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:2187–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14707.

Dolmazashvili E, Abutidze A, Chkhartishvili N, Karchava M, Sharvadze L, Tsertsvadze T. Regression of liver fibrosis over a 24-week period after completing direct-acting antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving care within the national hepatitis C elimination program in Georgia: Results of hepatology clinic HEPA exper. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1223–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000964.

Srinivasa Babu A, Wells ML, Teytelboym OM, et al. Elastography in chronic liver disease: modalities, techniques, limitations, and future directions. Radiographics. 2016;36:1987–2006. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016160042.

Ferraioli G, Tinelli C, Lissandrin R, et al. Point shear wave elastography method for assessing liver stiffness. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4787–96. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4787.

Iredale JP, Bataller R. Identifying molecular factors that contribute to resolution of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1160–4. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.019.

Curry MP, O’Leary JG, Bzowej N, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2618–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1512614.

Silva GF, de Andrade VG, Moreira A. Waiting DAAs list mortality impact in HCV cirrhotic patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55:343–5. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-2803.201800000-76.

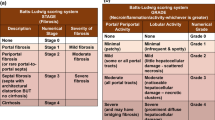

Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1996;24:289–93. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008690394.

Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). Recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2018;69: 461–511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026

Singh S, Facciorusso A, Loomba R, Falck-Ytter YT. Magnitude and kinetics of decrease in liver stiffness after antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(27–38):e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.038.

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77.

Witten IH, Frank E, Hall MA, Pal CJ. Data mining: practical machine learning tools and techniques. In: Fourth. Kaufmann M, editor. Elsevier; 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/C2015-0-02071-8

Chang J. Collapsed gibbs sampling methods for topic models. In: RDocumentation. Ida Package [Internet]. 2015. https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/lda/versions/1.4.2. Acessed 2 Out 2020.

Pan JJ, Bao F, Du E, et al. Morphometry confirms fibrosis regression from sustained virologic response to direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2:1320–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1228.

Toyoda H, Tada T, Yasuda S, Mizuno K, Ito T, Kumada T. Dynamic evaluation of liver fibrosis to assess the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved sustained virologic response. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:1208–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz359.

Yamada R, Hiramatsu N, Oze T, et al. Incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma change over time in patients with hepatitis C virus infection who achieved sustained virologic response. Hepatol Res. 2019;49:570–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13310.

Mallet V, Gilgenkrantz H, Serpaggi J, et al. Brief communication: the relationship of regression of cirrhosis to outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:399. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-6-200809160-00006.

Suda T, Okawa O, Masaoka R, et al. Shear wave elastography in hepatitis C patients before and after antiviral therapy. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:64–8. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i1.64.

Hamada K, Saitoh S, Nishino N, et al. Shear wave elastography predicts hepatocellular carcinoma risk in hepatitis C patients after sustained virological response. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195173.

Tarrant JM. Blood cytokines as biomarkers of in vivo toxicity in preclinical safety assessment: considerations for their use. Toxicol Sci. 2010;117:4–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfq134.

Aziz N, Detels R, Quint JJ, Gjertson D, Ryner T, Butch AW. Biological variation of immunological blood biomarkers in healthy individuals and quality goals for biomarker tests. BMC Immunol. 2019;20:2–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-019-0313-0.

Rios DA, Valva P, Casciato PC, et al. Chronic hepatitis C liver microenvironment: role of the Th17/Treg interplay related to fibrogenesis. Sci Rep. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13777-3.

Medel MLH, Reyes GG, Porras LM, et al. Prolactin induces IL-2 associated TRAIL expression on natural killer cells from chronic hepatitis C patients in vivo and in vitro. Endocrine Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2019;19:975–84. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530319666181206125545.

Winckler FC, Braz AMM, da Silva VN, et al. Influence of the inflammatory response on treatment of hepatitis C with triple therapy. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018;51:731–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0137-2018.

Langhans B, Nischalke HD, Krämer B, et al. Increased peripheral CD4+ regulatory T cells persist after successful direct-acting antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2017;66:888–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.12.019.

Abdelwahab SF. Cellular immune response to hepatitis-C-virus in subjects without viremia or seroconversion: Is it important? Infect Agent Cancer. 2016;11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-016-0070-0.

De Groen RA, Boltjes A, Hou J, et al. IFN-λ-mediated IL-12 production in macrophages induces IFN-γ production in human NK cells. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:250–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201444903.

Yang CM, Yoon JC, Park JH, Lee JM. Hepatitis C virus impairs natural killer cell activity via viral serine protease NS3. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0175793. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175793.

Fugier E, Marche H, Thélu MA, et al. Functions of liver natural killer cells are dependent on the severity of liver inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95614. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095614.

Zhu Z, Cai T, Fan L, et al. Clinical value of immune-inflammatory parameters to assess the severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:332–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.041.

Da Silva Neto PV, Carvalho JCS, Pimentel VE, et al. Prognostic value of sTREM-1 in COVID-19 patients: a biomarker 1 for disease severity and mortality Corresponding: 40. medRxiv. 2020; 1–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.22.20199703

Funding

The project was carried out with the financial support of FAPESP, process 2016/25416-3, and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel – Brazil (CAPES)—Funding Code 001 (grants).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMMB, RPS, MAG, and GFS were involved in conceptualization. AMMB, FCW, RPS, MAG, and GFS were involved in data curation. AMMB, RPS, MAG, and GFS were involved in formal analysis. AMMB, RPS, MAG, and GFS were involved in investigation. AMMB, FCW, LSB, LGC, LBML, RPS, MAG, and GFS were involved in methodology. MAG and GFS were involved in supervision. AMMB, AMMB, RSL, RPS, RMTG, MAG, and GFS were involved in writing—original draft. AMMB, RSL, RMTG, MAG, and GFS were involved in writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Botucatu Medical School, UNESP (protocol no. 2.810.759).

Consent to participate

All the included patients signed the informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data here presented are available to consult with the corresponding author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braz, A.M.M., Winckler, F.C., Binelli, L.S. et al. Inflammation response and liver stiffness: predictive model of regression of hepatic stiffness after sustained virological response in cirrhotics patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Exp Med 21, 587–597 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-021-00708-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-021-00708-w