Abstract

Background

Multiple sclerosis imposes a heavy burden on the person who suffers from it and on the relatives, due to the caregiving load involved. The objective was to analyse whether the inclusion of social costs in economic evaluations of multiple sclerosis-related interventions changed results and/or conclusions.

Methods

A systematic review was launched using Medline and the Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry of Tufts University (2000–2019). Included studies should: (1) be an original study published in a scientific journal, (2) be an economic evaluation of any multiple sclerosis-related intervention, (3) include productivity losses and/or informal care costs (social costs), (4) be written in English, (5) use quality-adjusted life years as outcome, and (6) separate the results according to the perspective applied.

Results

Twenty-nine articles were selected, resulting in 67 economic evaluation estimations. Social costs were included in 47% of the studies. Productivity losses were assessed in 90% of the estimations (the human capital approach was the most frequently used method), whereas informal care costs were included in nearly two-thirds of the estimations (applying the opportunity and the replacement-cost methods equally). The inclusion of social costs modified the figures for incremental costs in 15 estimations, leading to a change in the conclusions in 10 estimations, 6 of them changing from not recommended from the healthcare perspective to implemented from the societal perspective. The inclusion of social costs also altered the results from cost-effective to dominant in five additional estimations.

Conclusions

The inclusion of social costs affected the results/conclusions in multiple sclerosis-related interventions, helping to identify the most appropriate interventions for reducing its economic burden from a broader perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A shift towards a societal perspective in the economic assessment of healthcare technologies, including not only the payer’s or the provider’s point of view (direct costs), but also the impact on patients and their families and the public/societal expenditure (indirect costs), has been observed over the last decade [1]. The inclusion of non-healthcare costs or social costs such as informal care and/or productivity loss is gaining more and more importance as advances in treatment options, innovation in health technologies and new methods of diagnosis have provided new models of care. Due to medical advances, the management of several diseases has shifted from acute diseases with mainly hospital-based treatment to chronic diseases relying more and more on outpatient care with support from informal caregivers. Considering a broad perspective is particularly important when, in addition to the healthcare resources used and the effects on patients’ health, it is intended to evaluate interventions which can generate other types of significant effects on other social dimensions such as labour productivity, non-professional care time (informal care) or the health and well-being of other agents as well as those of the patients [2,3,4,5,6].

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune and neurodegenerative condition that affects the brain and spinal cord, causing a disfunction in part of the nervous system’s ability to transmit signals due to damage to the insulating covers of the nerve cells [7]. Some of the most common symptoms of MS entail difficulty in walking, vision problems and problems with balance and co-ordination [8, 9]. Those symptoms might be present before the diagnosis of the disease, since 85% of the individuals who later develop the condition begin with an episode of neurological disturbance, which is commonly known as a clinically isolated syndrome, which might progress over days or weeks [10]. In patients of working age, these symptoms could lead to short and long periods of absence from work. Since those people with a first appearance of symptoms have not yet been diagnosed, the societal impact (due to loss of productivity) could have been underestimated.

MS is particularly interesting to study since it is a disease associated with considerable healthcare and other social costs, due to early onset of symptoms which commonly manifest themselves in childhood and early adulthood (20 s and 30 s), and with a debilitating pathogenesis, making the disease one of the most common causes of disability in younger adults. Even though most people with MS are diagnosed at 20 to 50 years old, a recent study has shown that individuals with a diagnosis of MS at younger ages (during childhood) may develop a more severe stage of the disease after longer periods of time, even as long as 32 years after the diagnosis, than those individuals with a later diagnosis, who might worsen after 18 years, and who also take longer to reach disability milestones [11]. The onset of the disease affects the ability to work, as a recent study has revealed that the proportion of patients below retirement age who are employed or self-employed decreases as the severity of the illness increases [12], imposing a great burden in terms of societal costs (informal care costs and costs due to sick leave and early retirement), which can reach 60% of the total lifetime costs [13]. Thus, the symptomatology of MS leads patients and their families to greater needs of care (outside the healthcare system) and a severe curtailment of working life. This debilitating state of health also results in a lower quality of life [13], a higher risk of death and shorter life expectancies than in the general population without the disease [14,15,16,17,18], even though the availability of new treatments might be reducing those differences. Furthermore, due to advances in treatment options and diagnostic criteria, the costs of the disease have shifted from being mainly those of hospitalisation, to being those of outpatient care, which now accounts for 80–90% of MS-related healthcare costs [19, 20].

Apart from studies which focus entirely on the estimation of healthcare costs, the literature in the field of cost-of-illness studies reveals that non-healthcare costs, mainly those resulting from the loss of work and the cost of care associated with the loss of patients’ autonomy due to disability, represent a very high cost for society, being even higher than healthcare costs [12]. Furthermore, as the disease progresses and affects patients’ health more severely, social costs increase progressively, both in absolute value and in proportion to the total cost of MS [21]. Thus, apart from the effects on patients, the health of the closest relatives is also affected, as well as other aspects directly related to their well-being [22, 23].

However, and although several non-medical costs related to MS have been identified [24], which are usually out-of-pocket expenses, the most substantial non-medical costs associated with the disease have been shown to be productivity losses and informal caregiving costs [12]. A recent European study in 16 countries has shown that among MS sufferers who are below retirement age, only about 50% are employed (range from 31 to 65%). Those with no disruption on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) had a work capacity of 82%, but among those with maximum disability due to the disease, this capacity declined to 8% [12]. Studies have also shown that MS has a significant impact on family members; about 50% of MS sufferers receive informal care from family members, ranging from less than 50 h/month for people with mild symptoms to round-the-clock care for those with severe symptoms [12]. Moreover, as the disease becomes more debilitating over the years, work life and family life often become heavily affected, and there is a high impact on the health-related quality of life of the individual sufferers and their families, and a high impact on society as well [12, 25].

Despite the efforts developed in the field of burden and cost-of-illness studies, to the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence on the influence of considering the perspective of the society in economic evaluations of healthcare interventions on MS. The aim of the present work was, therefore, to study the effects of considering a broader perspective (societal) instead of the healthcare funder’s perspective in the economic assessment of MS-related healthcare interventions. Therefore, we tried to discover whether a consideration of society’s perspective would significantly modify the results and the recommendations of the economic evaluations performed.

Methods

Study design: search strategy and inclusion criteria

We performed a systematic literature review, using the methodological framework outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [26]. A search in the MEDLINE database using PubMed and the Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) Registry of Tufts University was performed, covering the period from 1st January 2000 to 31st October 2019. The two databases were selected to perform a comprehensive search covering a broad range of disciplines related to economic evaluations within the medical field. Since the CEA Registry is based on MEDLINE searches for articles using the keywords “QALYs”, “quality-adjusted” and “cost-utility analysis”, results would be expected to overlap [27]. However, studies have shown that searching in both databases ensures a more accurate search [28]. The search launched in PubMed included the subject headings (Mesh terms in PubMed) and targeted “keywords search” for the following two groups: (1) Economic evaluation (including the terms: “Costs and Cost Analysis”; “cost–effectiveness”; “cost–utility”; “cost–benefit”; “economic evaluation”; “economic analysis”; “QALY”; “quality-adjusted life years”) and (2) multiple sclerosis (including the terms: “multiple sclerosis”; “sclerosis”). We restricted our review to any original studies published in a scientific journal and including an economic evaluation of any intervention related to multiple sclerosis. However, studies were only included if social costs (informal care costs and/or productivity losses) were included in the analysis and results were provided separately for each perspective applied (healthcare provider/payer and societal perspectives). Moreover, studies had to use quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) as one of the outcomes of the analysis, and the results had to be given separately (or could be extracted) if other diseases were also included in the analysis. The search was restricted to studies conducted on humans and published in English. Studies were also excluded if they were reviews of economic evaluations, methodological studies or were not full economic evaluations, such as a cost-of-illness study, a burden-of-disease study or a budget impact analysis.

Overview and definitions

This review focuses on the cost-utility analysis, which measures the health outcomes in QALYs and the costs of multiple sclerosis-related interventions. Therefore, to reflect the true range of costs and outcomes of multiple sclerosis interventions, the analysis examines the interventions from both the healthcare perspective and the societal perspective.

For the purpose of the study, the concept of healthcare costs has been defined in accordance with the OECD report of 2000 (revised in 2011) “System of Health Accounts methodology proposed by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)” [29]. It is important to note that according to that definition, professional long-term care would be part of direct healthcare costs and is described as follows: “Total long-term care consists of a range of medical/nursing care services, personal care services and assistance services that are consumed with the primary goal of alleviating pain and suffering or reducing or managing the deterioration in health status in patients with a degree of long-term dependency”. Hence, in this study, direct healthcare costs included all medical resources as well as professional caregiving, which would constitute the perspective of the healthcare provider/payer, whereas social costs referred mainly to informal care (provided by non-professional caregivers) and to productivity costs due to loss of productivity. Therefore, the societal perspective would then add to the healthcare provider/payer’s perspective the costs due to informal care and productivity losses.

Study selection procedure and data extraction

To eliminate bias and errors in the methodology, the process of study selection and data extraction was double-blinded and was conducted using peer review. We followed a three-stage selection method based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. First, BRS screened the lists of selected titles and abstracts identified in the electronic literature searches, and full texts were retrieved if the abstract indicated that the study was an economic evaluation of multiple sclerosis or sclerosis and if it was written in English. Second, based on the inclusion criteria, two investigators (SD and BRS) independently conducted a full-text review and assessed each paper as included, excluded, or unsure. The individual screening results were compared, and discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (LMPL or IAR) conducting a full-text review. Final agreement was achieved through discussion among the research team members to achieve consensus. Third, relevant data from the selected articles were extracted using an Excel-based data extraction table specifying the following information: author’s full name, year of publication, journal, title, intervention type, country and currency, discount rate (costs/outcomes), time horizon, perspective applied (healthcare provider/payer or societal), costs and QALYs as a consequence of the intervention against its comparator from both perspectives, the threshold assumed for the economic evaluation, costs included (healthcare and social costs), and the method used for calculating social costs. The data-extracting process was also double-blinded, using peer review with two independent researchers (BRS and SD) extracting the data. Disagreements in the data-extracting phase were settled by introducing a third researcher (LMPL or IAR).

Data synthesis

Following the data extraction, a narrative synthesis of the results from the included studies was performed. To assess the influence of the inclusion of social costs (informal care costs and/or productivity losses) on the result and conclusion of the economic evaluations of total costs of MS interventions, information about the incremental cost-utility ratios (ICURs) was collected or calculated (if not given by the original authors of the study) from both perspectives. The ICURs were then compared to determine whether the inclusion of social costs in the analyses had affected the conclusion or results of the study based on the threshold value assumed by the authors. In this sense, two options could produce changes in results or in the conclusions. We recorded a change in the conclusions when the decision about the adoption of a new technology was changed as a result of the inclusion of the social costs. For instance, from the healthcare perspective, the ICUR was above the threshold value, so the assessed technology was not recommended. However, when social costs were included, the ICUR was below the corresponding threshold. On the other hand, a change in results was identified when social costs were introduced and (1) the ICUR fell below the threshold (as in the previous case referred to, when a change in results led to a change in conclusions) or (2) the intervention became cost-saving (although it was previously already cost-effective but had a positive ICUR). It is important to stress that a significant change in the results may not change the conclusions of the analysis, as explained in the latter case. For example, an intervention assessed with a favourable ICUR from the healthcare perspective would already be recommended. If the inclusion of social costs made the ratio significantly more favourable (or even dominant), there would have been a change in the results of the economic evaluation without leading to a change in the conclusions, as the evaluated intervention would have already been recommended from the healthcare perspective.

Results

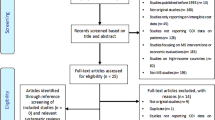

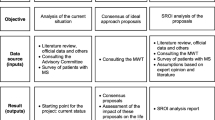

Based on the literature search in the 2 databases, 421 records were retrieved, after dropping duplicates (Fig. 1). After reviewing titles and abstracts, 301 were excluded because they did not meet the study criteria, leaving 120 records for full-text review. From these, 91 were additionally excluded for the following reasons: 22 were not full economic evaluations and eight were not evaluations of multiple sclerosis (or, if other diseases were included in the analysis, the results regarding MS could not be separated). Out of the 61 economic evaluations on multiple sclerosis that were excluded, 48 did not include social costs in their estimations, 11 did not separate perspectives (healthcare payer/provider from the societal perspective) and two papers did not use QALYs as outcome. Hence, 29 studies met the inclusion criteria and were finally included in the literature review [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58].

Study characteristics

Almost three-quarters of the studies considered either multiple sclerosis in general (11 studies, 38%), without specifying the type of MS [33, 36, 39, 42, 44, 47, 51,52,53,54, 57], or relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in another 11 studies [31, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 50, 55, 56]. Another two studies exclusively referred to people with secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis [45, 46]; one study focussed on slow-progression multiple sclerosis [30], progressive multiple sclerosis [32] and subsequent multiple sclerosis [49]; and another one on relapsing–remitting or secondary multiple sclerosis [48] and on secondary-progressive or progressive relapsing multiple sclerosis [58].

Of the 29 studies included in the analysis, 8 were performed in the United Kingdom [30, 32, 38,39,40, 51, 53, 57]; 7 in the United States [31, 35, 36, 50, 52, 54, 58]; 5 in Sweden [33, 44,45,46,47]; 2 were performed in France [34, 48]; 2 in Italy[37, 49]; 2 Iran [41, 56]; and 1 study was performed in Canada [42], 1 in Serbia [43] and 1 in Finland [55] (Table 1).

Most often, the assessed interventions (22) were pharmaceutical treatments [33,34,35, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47, 49, 50, 52,53,54,55,56, 58]. However, three studies evaluated mixed interventions in care delivery and pharmaceutical procedures [31, 36, 48], two focussed on non-pharmacological treatments [30, 32], one was on a care delivery intervention [51] and another one was a health education or behaviour programme [57]. Among the pharmaceutical interventions, single or jointly with another type of intervention, only 1 concerned a symptom-disease management therapy, i.e. cannabis [39], and the remaining 23 evaluated a disease-modifying therapy: 12 studies assessed an injectable medication alone [31, 33, 41,42,43, 45,46,47, 49, 52,53,54], 5 additional articles individually evaluated an infused medication [36,37,38, 44, 56], and another two performed their economic evaluations solely on an oral medication [34, 50]. Two studies assessed the use of injectable and infused medications [35, 58], another one evaluated oral and infused medications together [40], and another article considered oral and injectable medications together [55].

Lifetime was the most frequently used time horizon for the evaluations [31, 33,34,35, 41, 53, 54] while the other studies used different time lapses depending on the type of intervention. With regard to the perspective applied, 12 studies used the societal perspective as the main point of view in the analysis [31,32,33, 36,37,38, 41, 46,47,48, 52, 54], in which the perspective of the healthcare payer/provider could be extracted from the text or tables, or appeared as a secondary analysis. Eleven studies performed the evaluation from both perspectives [34, 35, 42,43,44,45, 49, 51, 53, 56, 58], and the other 6 studies [30, 39, 40, 50, 55, 57] included the societal perspective in a secondary analysis (Table 1).

Only three studies exclusively included informal care costs [30, 32, 39], 11 studies only estimated labour productivity losses due to multiple sclerosis [31, 34, 35, 37, 38, 41,42,43, 55,56,57], while the other 15 studies included both types of social costs [33, 36, 40, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, 58]. With regard to the valuation of informal care costs, if stated, the opportunity cost [36, 49, 52] and the replacement cost [30, 51, 53] methods were used equally in three studies. Another 12 studies did not provide information about the method used to value informal care costs. Two of the papers that applied the opportunity-cost method explicitly stated that both paid and unpaid time were valued [36, 49]. Frasco et al. (2017) [36] indicated that leisure time was valued as 65% of the average net income, whereas Lazzaro et al. (2009) [49] imputed a unit cost equal to €5.90 per hour for unpaid time. Pan et al. (2012) [54] only considered leisure time when evaluating informal care costs.

In the case of labour productivity losses, the human capital approach was used in 15 studies [31, 33,34,35,36,37, 41,42,43, 48, 49, 51, 52, 56, 57] if the authors explicitly reported the method used. Ten additional studies did not mention the approach used to value productivity losses. The friction-cost method was used in only one paper [53], differentiating the valuation of paid and unpaid time as follows: in the case of labour productivity losses due to absenteeism, each working hour lost was valued as 80% of the average value of a worker’s productivity; and the time lost by inactive individuals was valued at 40% of the average wage. Absenteeism was actually the main component of labour productivity losses, and was included in 14 studies [33,34,35,36, 44,45,46,47,48,49, 51, 53, 54, 57], whereas early retirement was included in 9 studies [33, 34, 36, 44,45,46,47,48, 54], temporary disability in 6 [34, 36, 45,46,47,48], premature mortality in 2 [54, 56] and presenteeism in 1 [54].

Results of economic evaluations

Table 2 displays the results obtained from the 67 economic evaluations (EEs) resulting from the 29 articles included in this review.

The inclusion of social costs changed the incremental costs of the assessed intervention versus its comparator in 15 economic evaluation estimations. Although still positive (having higher costs than the comparator) when social costs were considered, the incremental costs were reduced so as to make the corresponding ICUR fall below the comparative threshold in three cases. In another one, the opposite pattern was observed. Moreover, in eight additional estimations, from the societal perspective the incremental costs of the assessed intervention changed from being positive to negative, implying that the evaluated intervention was cost-saving against its comparator. Three additional estimations showed the contrary trend: positive incremental costs from the societal perspective, but cost-saving from the perspective of the healthcare payer/provider.

In view of the aforementioned changes in incremental costs due to the inclusion of social costs (informal care costs and/or productivity losses), the conclusions were modified in ten EEs (almost 15% of the EEs analysed in the review). Economic evaluations 35, 36 and 37 showed that, when informal care and labour productivity losses were included, the procedure that was the subject of analysis became cost-effective, as its cost per additional QALY lay below the €30,000 threshold set by the authors, compared to its lack of cost-effectiveness from the healthcare payer’s perspective. Moreover, in three EEs, the inclusion of social costs (labour productivity losses only in the case of EEs 14 and 15 and both types of social costs for EE 66) resulted in a more dramatic change: the assessed interventions became dominant from the societal perspective (lower costs and higher health gains), when, from the healthcare payer’s perspective, they were not cost-effective. Conversely, in EEs numbers 9, 10 and 12, the assessed intervention was cost-effective when the analysis was performed from the healthcare payer’s perspective, but it became dominated by the comparator when social costs were included, owing to higher incremental costs. Economic evaluation 65 showed that once labour productivity losses were considered, the intervention was no longer cost-effective, as it was from the perspective of the healthcare payer/provider.

Moreover, and although not involving any change in the conclusions as in the ten estimations described above, the inclusion of social costs did show a change in results in five additional EEs (more than 7% of the total number of EEs): the EEs numbered 17, 20, 33, 45 and 58 became not only cost-effective, as they were already from the healthcare payer/provider’s perspective, but also dominant after the inclusion of social costs, because, in addition to being better in terms of health outcomes, they were cost- saving.

From the healthcare payer/provider’s perspective, 12 EEs (17.91%) reported negative incremental costs (estimations number 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 16, 21, 22, 46, 47 and 63), pointing towards the assessed intervention being cost-saving against the comparator. However, only eight (11.94%) of them led to the conclusion that the intervention was dominant (estimations number 6, 7, 16, 21, 22, 46, 47 and 63). On the other hand, if the societal perspective was applied, 17 estimations (25.37%) showed negative incremental costs (estimations number 6, 7, 8, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 33, 45, 46, 47, 58, 63 and 66), all of which, apart from 1 EE, proved to be dominant, leading to lower costs and higher gains in QALY. Another remarkable result is the one obtained in the two EEs (number 21 and 22) from the study carried out by Hettle et al. (2018) [40] and in estimation number 63 by Taheri et al. (2019) [56] when comparing the results from the healthcare payer’s perspective with those from the societal perspective. In all the scenarios, the assessed intervention was cost-saving and led to gains in health, but both economic and QALY outcomes were higher from the societal perspective, when carers’ utilities were incorporated, showing that pharmaceutical interventions also reported benefits to informal caregivers. These were the only studies that additionally took into account the informal carers’ utilities when applying the societal perspective.

With regard to the incremental cost-utility ratios (ICURs), from the healthcare perspective, 18 (26.87%) EEs (number 8, 9, 10, 12, 17, 18, 19, 20, 33, 44, 45, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 64 and 65) proved to be cost-effective (ICUR below the corresponding threshold value). From the societal perspective, 12 ICURs were below the threshold and were thus cost-effective (EEs number 8, 18, 19, 35, 36, 37, 44, 55, 56, 57, 59 and 64).

Figure 2 shows the dispersion of the costs and QALYs of the 67 economic evaluation estimations included, according to the perspective applied. The most noticeable effect is that several interventions that had intermediate values of between €30,000 and 50,000/QALY fall below the threshold of €30,000/QALY or are even cost-saving when the societal perspective is applied.

Discussion

In this review, we sought to explore changes that might occur due to the application of different costing perspectives (that of the health financier/provider or that of society) to economic evaluations of MS interventions. To fill the gap in the existing literature, the objective of this review was twofold. First, to identify the number of economic evaluations, carried out from a societal perspective, of the treatments related to multiple sclerosis. Second, to investigate the effect that the choice of perspective (societal versus healthcare provider’s or payer’s perspective) has on the results and conclusions of the economic evaluations implemented in this area. Our analysis shows that the results and possible recommendations for decision-makers can differ depending on the perspective selected.

In relation to the first objective, the proportion of articles about economic evaluations that include the societal perspective in the field of multiple sclerosis is noteworthy. Almost half of the articles (47%; 42 out of 90 papers) used the societal perspective. This proportion is notably higher than that found in the area of treatments for rare diseases, where a review found that only 11% of the studies included a societal perspective[59], a ratio slightly higher than that found for the area of depression (42%) [60], but lower than that found for interventions in Alzheimer’s disease (58%) [61].

In the economic evaluations which include a societal perspective, a further difference was found between the types of social costs that were included in the estimations for MS and those included in the economic evaluations of other diseases. In the case of MS, the majority of EEs (about 90%) that considered the societal perspective analysed costs associated with labour productivity losses. This finding is quite similar to that for diseases such as depression (95% of EEs that considered the societal perspective estimated labour productivity losses) and rare diseases (about 80%). However, in other diseases such as Alzheimer’s, this figure barely reaches 3% [59,60,61]. The differences are even higher when considering the existence of informal care costs. In multiple sclerosis, about 65% of the EEs that considered the societal perspective included informal care costs, only surpassed in studies of Alzheimer’s, 97% of which included these costs, whereas for diseases such as depression and rare diseases, the opposite trend was shown, with only 29 and 22% of the respective studies including informal care costs.

Finding the reason for these differences in the weight and/or the presence of informal care costs and productivity losses, depending on the diseases considered, is neither clear nor intuitive. They could be explained by the nature of the disease (for example, by the age at onset). Thus, in the case of Alzheimer’s, rare diseases or multiple sclerosis, the costs may be shared between the patients (through productivity losses) and the family (through informal care costs), whereas in the case of depression, the burden could be mainly supported by individuals (through loss of work). In case of the latter disease, it would seem that the burden is still usually considered as a problem for the patient as an individual (through loss of work), and the financial strains on the affected family are not taken into consideration. As has been previously stated, multiple sclerosis is often diagnosed at early ages, even during childhood or early adulthood [11], and leads to disability and a reduced health-related quality of life over time [16, 17]. As a result, societal costs, such as productivity losses and formal and informal long-term care costs, can be incurred from early ages and throughout the rest of life [13]. On the other hand, the differences might be explained by the fact that the inclusion of certain types of costs, such as informal care costs, has not been considered until recently in the literature about some diseases, and it is still a challenge to be faced in cost-of-illness and economic evaluation studies [62, 63].

It is not easy to know why the societal perspective is more evident in connection with some diseases compared to others since there is evidence that the social costs associated with them are very substantial. In the case of MS, two studies conducted as long as 20 years ago highlighted the importance of informal care costs in some European countries [64], especially in the United Kingdom [46, 64] and in Italy [65], where they were the main societal costs, and this was confirmed by later European studies[23, 66]. In fact, social costs can be as high as healthcare costs in the four diseases previously mentioned (Alzheimer’s disease, rare diseases, depression and MS). In any case, it is surprising that the proportion of economic evaluations that consider the societal perspective was not higher, when a large number of countries, such as Sweden, the Netherlands and France [67,68,69], either recommend using the societal perspective or point out the importance of using both the societal perspective and that of the healthcare financier, as in Spain and Italy [70, 71]. Other countries have opted for the perspective of the healthcare funder but allow, as a supplementary analysis, the inclusion of the societal perspective (Australia, Canada, the Baltic countries, Belgium and Poland, among others) [72,73,74,75,76]. Even in the case of England and Wales, although the main perspective is that of the healthcare funder, in appropriate cases the inclusion of personal social services (PSS) is allowed [77].

With regard to the second objective of the review, the inclusion of social costs modified the incremental costs of the assessed interventions versus their comparators in 15 economic evaluation estimations. In 10 of them (14.9% of the 67 economic evaluations reviewed in this work), the use of the societal perspective could modify the recommendations/conclusions of the evaluations. In six cases, the consideration of social costs made the evaluated intervention cost-effective compared to its comparator, but in four other cases the effect was the opposite, and the evaluated intervention was no longer cost-effective against its comparator. Even though the inclusion of social costs did not affect the adoption of the assessed intervention in all the estimations, it is also worth mentioning that it did produce a change in results in 7.5% of the economic evaluations analysed, which changed from having a good cost-effectiveness ratio from a healthcare perspective to being dominant from a societal point of view. When comparing these results with other diseases (such as depression, Alzheimer’s and rare diseases), it was observed that, even though consideration of the societal perspective had a positive influence by changing the interventions in those diseases to dominant (cost-saving) [59,60,61], this positive effect was weaker than in the case of MS, in which the inclusion of social costs led to a larger number of changes in the incremental costs. This might be explained by the nature of the interventions performed within these diseases, as in the case of MS they are mainly pharmaceutical interventions with a lifetime horizon. In addition, when analysing the changed conclusions in some interventions, some reasons could be considered. First, because when the interventions are medical procedures, the differences in social costs are usually smaller than those in non-medical procedures, such as pharmaceutical interventions [61]. Second, because for those interventions whose time horizon is longer (10 years, even more, or even lifetime), the difference in social costs is greater than for those interventions whose time horizon is shorter (less than 3 years).

From a methodological point of view, the lack of transparency in many of the studies analysed is particularly worrying. In two-thirds of the articles which included the costs of informal care as part of the costs analysed from the societal perspective, the method of assessing informal care time was not made explicit by the original authors of the study. Of the six articles which specified the method used, three used the opportunity-cost approach and in the other three, the replacement-cost approach was used. Of the 26 articles that included productivity losses, 10 of them (38.5%) did not specify the method used. Of the 16 studies that indicated the approach, 15 used the human capital as the method, while only one study used the alternative approach of friction costs. It should be noted that high heterogeneity was identified in the items valued as productivity losses. Some articles only included absenteeism, while other papers included presenteeism, permanent sick leave, early retirement, and premature mortality.

Some limitations should also be taken into account when interpreting our findings. However, most of these limitations were due to the lack of homogeneity in the information provided by the original authors. First, since no homogeneous methodology was observed among the studies included (i.e., method used to value productivity losses and/or informal care costs, detailed information about social cost components), the comparability between studies might be compromised. Second, we did not aim to reassess the evaluated healthcare interventions in each original study, but to review whether the inclusion of the societal perspective could modify the conclusion. However, the authors considered different time horizons, discount rates, healthcare costs and cost-effectiveness thresholds, which may also limit the comparability of results. Moreover, the stage of the disease might be a relevant factor behind the economic burden of the condition, but there is no consistency in relation to this question, since 10 studies did not specify the degree of severity [33, 36, 39, 42, 44, 48, 51,52,53,54, 57], while 11 studies referred to relapsing–remitting MS individually [31, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 50, 55, 56] and the other 8 studies considered slow or secondary-progressive MS, solely or jointly with relapsing–remitting MS. Lastly, the search strategy in relation to the databases used might be subject to debate. However, we complemented our search launched in Medline by additionally using the CEA Registry of Tufts University, which applies an algorithm also launched in Medline and a systematic review process [27, 78].

To conclude, the systematic review performed indicates that the adoption of a societal perspective would modify the results of economic evaluations of MS-related interventions, as well as the conclusions about their implementation. Therefore, consideration of the perspective used in the economic evaluations carried out in the field of MS, far from being neutral, can lead to important consequences in relation to the information generated for decision-makers. Excluding the societal perspective when performing economic evaluations in diseases such as MS could lead to the omission of relevant information for decision-makers, and could even result in a misguided recommendation about whether a new and available treatment should be adopted or not. In addition, to be truly social, the societal perspective should also include the effect on caregivers’ health status. It is remarkable that, although almost two-thirds of the selected economic evaluations included informal care costs, only two studies [40, 56] also considered the effects of the assessed intervention on the caregivers’ health. Such effects could be highly important in view of the economic burden borne by caregivers of people with MS, and because interventions aimed at improving the care of people with this disease have been shown not only to lead to better states of health of both caregivers and care receivers [79, 80], but also to maintain those positive effects even after the intervention has finished [80], suggesting that caregivers might be an appropriate and independent target for more focussed MS-related therapeutic strategies. In fact, one of the major recommendations of recent caregiver reports [81,82,83] is to include the caregiver in the care receiver’s care plan. Hence, the effect of implementing healthcare interventions on the well-being and health of those providing care, which might additionally entail the identification of consequential effects, may come to prominence as a need for methodological improvement that should be taken into account in future studies. Moreover, in future studies, the stage of MS should also be a key factor when assessing the economic evaluation of new drugs, because some studies have already provided evidences of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments in delaying the progression to secondary-progressive MS and evidence of the effectiveness of an early start of the treatment [84, 85]. In addition, when interpreting the results by geographical location, the distribution of total costs between healthcare costs, professional and non-professional care costs, and labour productivity losses might be subject to country-specific employment and social policies, as there are notable differences between countries [86, 87]. Future analyses could aim to clarify the way in which the composition of costs differs among the countries where the economic evaluations are performed, as well as their relationship with social protection policies.

For ease of comparison, results are shown in additional euros per additional QALY. For this, the euro-currency exchange rates of the year of each article were applied. The values were not updated to any base year since the efficiency thresholds applied as a usual reference are usually kept constant over several years. In this sense, and to facilitate the interpretation of the results, two vectors were drawn with the values of €30,000/QALY and €50,000/QALY. These values were adopted as they are frequently cited thresholds in the economic evaluation literature.

References

Polimeni, J.M., Vichansavakul, K., Iorgulescu, R.I., Chandrasekara, R.: Why perspective matters in health outcomes research analyses. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 12, 1503–1512 (2013)

Brouwer, W.: The inclusion of spillover effects in economic evaluations: Not an optional extra. Pharmacoeconomics 37, 451–456 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0730-6

Drost, R.M.W.A., Paulus, A.T.G., Evers, S.M.A.A.: Five pillars for societal perspective. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health. Care. 36, 72–74 (2020)

Jönsson, B.: Ten arguments for a societal perspective in the economic evaluation of medical innovations. Eur. J. Health. Econ. 10, 357–359 (2009)

Oliva, J., Brosa, M., Espín, J., Figueras, M., Trapero, M., Key4Value-Grupo: Controversial issues in economic evaluation (I): Perspective and costs of health care interventions. Rev. Esp. Salud. Publica 89, 5–14 (2015). https://doi.org/10.4321/S1135-57272015000100002

Wittenberg, E., James, L.P., Prosser, L.A.: Spillover effects on caregivers’ and family members’ utility: A systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 37, 475–499 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00768-7

Zagon, I.S., McLaughlin, P.J.: Multiple sclerosis: Perspectives in treatment and pathogenesis. Codon PublicationsBrisbane, Australia (2017)

Tsang, B.K., Macdonell, R.: Multiple sclerosis- diagnosis, management and prognosis. Aust. Fam. Physician. 40, 948–955 (2011)

Koriem, K.M.M.: Multiple sclerosis: New insights and trends. Asian. Pacific. J. Trop. Biomed. 6, 429–440 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.03.009

Miller, D., Barkhof, F., Montalban, X., Thompson, A., Filippi, M.: Clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis, part I: natural history, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis. Lancet. Neurol. 4, 281–288 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(05)70071-5

Harding, K.E., Liang, K., Cossburn, M.D., Ingram, G., Hirst, C.L., Pickersgill, T.P., Te Water Naude, J., Wardle, M., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Robertson, N.P.: Long-term outcome of paediatric-onset multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 84, 141–147 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-303996

Kobelt, G., Thompson, A., Berg, J., Gannedahl, M., Eriksson, J., Group, M.S., Platform, E.M.S.: New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Multe. Scler. J. 23, 1123–1136 (2017)

Palmer, A.J., van der Mei, I., Taylor, B.V., Clarke, P.M., Simpson, S., Jr., Ahmad, H.: Modelling the impact of multiple sclerosis on life expectancy, quality-adjusted life years and total lifetime costs: Evidence from Australia. Mult. Scler. 26, 411–420 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458519831213

Kingwell, E., van der Kop, M., Zhao, Y., Shirani, A., Zhu, F., Oger, J., Tremlett, H.: Relative mortality and survival in multiple sclerosis: findings from British Columbia. Canada. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 83, 61–66 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2011-300616

Scalfari, A., Knappertz, V., Cutter, G., Goodin, D.S., Ashton, R., Ebers, G.C.: Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 81, 184–192 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829a3388

Marrie, R.A., Elliott, L., Marriott, J., Cossoy, M., Blanchard, J., Leung, S., Yu, N.: Effect of comorbidity on mortality in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 85, 240–247 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001718

Lunde, H.M.B., Assmus, J., Myhr, K.M., Bø, L., Grytten, N.: Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: A 60-year longitudinal population study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 88, 621–625 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2016-315238

Leray, E., Moreau, T., Fromont, A., Edan, G.: Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis. Rev. Neurol. (Paris). 172, 3–13 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2015.10.006

Briggs, F.B.S., Thompson, N.R., Conway, D.S.: Prognostic factors of disability in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 30, 9–16 (2019)

McKay, K.A., Hillert, J., Manouchehrinia, A.: Long-term disability progression of pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Neurology 92, e2764–e2773 (2019)

Ernstsson, O., Gyllensten, H., Alexanderson, K., Tinghög, P., Friberg, E., Norlund, A.: Cost of illness of multiple sclerosis-a systematic review. PLoS. One 11, e0159129 (2016)

Maguire, R., Maguire, P.: Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: Recent trends and future directions. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-020-01043-5

Parisé, H., Laliberté, F., Lefebvre, P., Duh, M.S., Kim, E., Agashivala, N., Abouzaid, S., Weinstock-Guttman, B.: Direct and indirect cost burden associated with multiple sclerosis relapses: excess costs of persons with MS and their spouse caregivers. J. Neurol. Sci. 330, 71–77 (2013)

Nicholas, R.S., Heaven, M.L., Middleton, R.M., Chevli, M., Pulikottil-Jacob, R., Jones, K.H., Ford, D.V.: Personal and societal costs of multiple sclerosis in the UK: A population-based MS Registry study. Mult. Scler. J-Exp, Transl. Clin. 6, 2055217320901727 (2020)

García-Domínguez, J.M., Maurino, J., Martínez-Ginés, M.L., Carmona, O., Caminero, A.B., Medrano, N., Ruíz-Beato, E.: Economic burden of multiple sclerosis in a population with low physical disability. BMC. Public. Health (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6907-x

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G., Group p: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS. Med 6, e1000097 (2009)

Thorat, T., Cangelosi, M., Neumann, P.J.: Skills of the trade: The tufts cost-effectiveness analysis registry. J. Benefit-Cost. Anal. 3, 1–9 (2012)

Saret, C.J., Winn, A.N., Shah, G., Parsons, S.K., Lin, P.J., Cohen, J.T., Neumann, P.J.: Value of innovation in hematologic malignancies: A systematic review of published cost-effectiveness analyses. Blood 125, 1866–1869 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-07-592832

OECD/Eurostat/WHO: A System of Health Accounts 2011: Revised edition. OECD Publishing, Paris (2017). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270985-en

Ball, S., Vickery, J., Hobart, J., Wright, D., Green, C., Shearer, J., Nunn, A., Cano, M.G., MacManus, D., Miller, D., Mallik, S., Zajicek, J.: The cannabinoid use in progressive inflammatory brain disease (CUPID) trial: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled parallel-group multicentre trial and economic evaluation of cannabinoids to slow progression in multiple sclerosis. Health. Technol. Assess (2015). https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19120

Bell, C., Graham, J., Earnshaw, S., Oleen-Burkey, M., Castelli-Haley, J., Johnson, K.: Cost-effectiveness of four immunomodulatory therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A Markov model based on long-term clinical data. J. Manag. Care. Pharm. 13, 245–261 (2007). https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.3.245

Bogosian, A., Chadwick, P., Windgassen, S., Norton, S., McCrone, P., Mosweu, I., Silber, E., Moss-Morris, R.: Distress improves after mindfulness training for progressive MS: A pilot randomised trial. Mult. Scler. 21, 1184–1194 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458515576261

Caloyeras, J.P., Zhang, B., Wang, C., Eriksson, M., Fredrikson, S., Beckmann, K., Knappertz, V., Pohl, C., Hartung, H.P., Shah, D., Miller, J.D., Sandbrink, R., Lanius, V., Gondek, K., Russell, M.W.: Cost-effectiveness analysis of interferon beta-1b for the treatment of patients with a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Clin. Ther. 34, 1132–1144 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.03.004

Chevalier, J., Chamoux, C., Hammes, F., Chicoye, A.: Cost-effectiveness of treatments for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: A French societal perspective. PLoS. ONE 11, e0150703 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150703

Earnshaw, S.R., Graham, J., Oleen-Burkey, M., Castelli-Haley, J., Johnson, K.: Cost effectiveness of glatiramer acetate and natalizumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Appl. Health. Econ. Health. Policy. 7, 91–108 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/11314900-000000000-0000010.1007/bf03256144

Frasco, M.A., Shih, T., Incerti, D., Diaz Espinosa, O., Vania, D.K., Thomas, N.: Incremental net monetary benefit of ocrelizumab relative to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a. J. Med. Econ. 20, 1074–1082 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2017.1357564

Furneri, G., Santoni, L., Ricella, C., Prosperini, L.: Cost-effectiveness analysis of escalating to natalizumab or switching among immunomodulators in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Italy. BMC. Health. Serv. Res. 19, 436 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4264-1

Gani, R., Giovannoni, G., Bates, D., Kemball, B., Hughes, S., Kerrigan, J.: Cost-effectiveness analyses of natalizumab (Tysabri) compared with other disease-modifying therapies for people with highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in the UK. Pharmacoeconomics 26, 617–627 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826070-00008

Gras, A., Broughton, J.: A cost-effectiveness model for the use of a cannabis-derived oromucosal spray for the treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes. Res. 16, 771–779 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2016.1140574

Hettle, R., Harty, G., Wong, S.L.: Cost-effectiveness of cladribine tablets, alemtuzumab, and natalizumab in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis with high disease activity in England. J. Med. Econ. 21, 676–686 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1461630

Imani, A., Golestani, M.: Cost-utility analysis of disease-modifying drugs in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Iran. Iran. J. Neurol. 11, 87–90 (2012)

Iskedjian, M., Walker, J.H., Gray, T., Vicente, C., Einarson, T.R., Gehshan, A.: Economic evaluation of Avonex (interferon beta-Ia) in patients following a single demyelinating event. Mult. Scler. 11, 542–551 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458505ms1211oa

Jankovic, S.M., Kostic, M., Radosavljevic, M., Tesic, D., Stefanovic-Stoimenov, N., Stevanovic, I., Rakovic, S., Aleksic, J., Folic, M., Aleksic, A., Mihajlovic, I., Biorac, N., Borlja, J., Vuckovic, R.: Cost-effectiveness of four immunomodulatory therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a Markov model based on data a Balkan country in socioeconomic transition. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 66, 556–562 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2298/vsp0907556j

Kobelt, G., Berg, J., Lindgren, P., Jonsson, B., Stawiarz, L., Hillert, J.: Modeling the cost-effectiveness of a new treatment for MS (natalizumab) compared with current standard practice in Sweden. Mult. Scler. 14, 679–690 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458507086667

Kobelt, G., Jönsson, L., Fredrikson, S.: Cost-utility of interferon beta(1b) in the treatment of patients with active relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Health. Econ. 4, 50–59 (2003)

Kobelt, G., Jonsson, L., Henriksson, F., Fredrikson, S., Jonsson, B.: Cost-utility analysis of interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health. Care. 16, 768–780 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462300102041

Kobelt, G., Jonsson, L., Miltenburger, C., Jonsson, B.: Cost-utility analysis of interferon beta-1B in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis using natural history disease data. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health. Care. 18, 127–138 (2002)

Kobelt, G., Texier-Richard, B., Lindgren, P.: The long-term cost of multiple sclerosis in France and potential changes with disease-modifying interventions. Mult. Scler. 15, 741–751 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458509102771

Lazzaro, C., Bianchi, C., Peracino, L., Zacchetti, P., Uccelli, A.: Economic evaluation of treating clinically isolated syndrome and subsequent multiple sclerosis with interferon beta-1b. Neurol. Sci. 30, 21–31 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-009-0015-0

Mauskopf, J., Fay, M., Iyer, R., Sarda, S., Livingston, T.: Cost-effectiveness of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis in the United States. J. Med. Econ. 19, 432–442 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2015.1135805

Mosweu, I., Moss-Morris, R., Dennison, L., Chalder, T., McCrone, P.: Cost-effectiveness of nurse-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) compared to supportive listening (SL) for adjustment to multiple sclerosis. Health. Econ. Rev (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-017-0172-4

Noyes, K., Bajorska, A., Chappel, A., Schwid, S.R., Mehta, L.R., Weinstock-Guttman, B., Holloway, R.G., Dick, A.W.: Cost-effectiveness of disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology 77, 355–363 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182270402

Nuijten, M.J., Hutton, J.: Cost-effectiveness analysis of interferon beta in multiple sclerosis: A Markov process analysis. Value. Health. 5, 44–54 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51052.x

Pan, F., Goh, J.W., Cutter, G., Su, W., Pleimes, D., Wang, C.: Long-term cost-effectiveness model of interferon beta-1b in the early treatment of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Clin. Ther. 34, 1966–1976 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.07.010

Soini, E., Joutseno, J., Sumelahti, M.L.: Cost-utility of first-line disease-modifying treatments for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Clin. Ther. 39, 537-557.e510 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.01.028

Taheri, S., Sahraian, M.A., Yousefi, N.: Cost-effectiveness of alemtuzumab and natalizumab for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treatment in Iran: decision analysis based on an indirect comparison. J. Med. Econ. 22, 71–84 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1543189

Tosh, J., Dixon, S., Carter, A., Daley, A., Petty, J., Roalfe, A., Sharrack, B., Saxton, J.M.: Cost effectiveness of a pragmatic exercise intervention (EXIMS) for people with multiple sclerosis: economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial. Mult. Scler. 20, 1123–1130 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458513515958

Touchette, D.R., Durgin, T.L., Wanke, L.A., Goodkin, D.E.: A cost-utility analysis of mitoxantrone hydrochloride and interferon beta-1b in the treatment of patients with secondary progressive or progressive relapsing multiple sclerosis. Clin. Ther. 25, 611–634 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80100-5

Aranda-Reneo, I., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Peña-Longobardo, L.M., Oliva-Moreno, J., López-Bastida, J.: Can the consideration of societal costs change the recommendation of economic evaluations in the field of rare diseases? An. Empir. Anal. Value. Health. 24, 431–442 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.10.014

Duevel, J.A., Hasemann, L., Peña-Longobardo, L.M., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Aranda-Reneo, I., Oliva-Moreno, J., López-Bastida, J., Greiner, W.: Considering the societal perspective in economic evaluations: A systematic review in the case of depression. Health. Econ. Rev (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-020-00288-7

Peña-Longobardo, L.M., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Oliva-Moreno, J., Aranda-Reneo, I., López-Bastida, J.: How relevant are social costs in economic evaluations? The case of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Health. Econ. 20, 1207–1236 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-019-01087-6

Oliva-Moreno, J., Trapero-Bertran, M., Peña-Longobardo, L.M., Del Pozo-Rubio, R.: The valuation of informal care in cost-of-illness studies: A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 35, 331–345 (2017)

Hoefman, R.J., van Exel, J., Brouwer, W.: How to include informal care in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 31(12), 1105–19 (2013)

Murphy, N., Confavreux, C., Haas, J., König, N., Roullet, E., Sailer, M., Swash, M., Young, C., Mérot, J.L.: Economic evaluation of multiple sclerosis in the UK, Germany and France. Pharmacoeconomics. 13, 607–622 (1998)

Amato, M.P., Battaglia, M.A., Caputo, D., Fattore, G., Gerzeli, S., Pitaro, M., Trojano, M.: The costs of multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional, multicenter cost-of-illness study in Italy. J. Neurol. 249, 152–163 (2002)

Sobocki, P., Pugliatti, M., Lauer, K., Kobelt, G.: Estimation of the cost of MS in Europe: extrapolations from a multinational cost study. Mult. Scler. 13, 1054–1064 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458507077941

The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benfits Agency (TLV). General guidelines for economic evaluations from the Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency. https://tools.ispor.org/PEguidelines/countrydet.asp?c=21&t=1 (2017). Accessed 5 May 2021

Zorginstituut Nederland. Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare. Zorginstituut Nederland, Diemen. https://tools.ispor.org/PEguidelines/source/Netherlands_Guideline_for_economic_evaluations_in_healthcare.pdf (2016). Accessed 15 May 2021

Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS). Choices in methods for economic evaluation. Haute Autorité de Santé. https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-11/choices_in_methods_for_economic_evaluation_-_2011.pdf (2012). Accessed 15 May 2021

Capri, S., Ceci, A., Terranova, L., Merlo, F., Mantovani, L.: Guidelines for economic evaluations in Italy: Recommendations from the Italian group of pharmacoeconomic studies. Drug. Inf. J. 35, 189–201 (2001)

Lopez-Bastida, J., Oliva, J., Antonanzas, F., García-Altés, A., Gisbert, R., Mar, J., Puig-Junoy, J.: Spanish recommendations on economic evaluation of health technologies. Eur. J. Health. Econ. 11, 513–520 (2010)

Canadian agency for drugs and technologies in health. Guidelines for the Economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada. 4th ed. CADTH https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/guidelines_for_the_economic_evaluation_of_health_technologies_canada_4th_ed.pdf (2017) Accessed 15 May 2021

Behmane, D., Lambot, K., Irs, A., Steikunas, N.: Baltic guideline for economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals (pharmacoeconomic analysis). https://tools.ispor.org/PEguidelines/source/Baltic-PE-guideline.pdf (2002). Accessed 15 May 2021

Agency for health technology assessment. Guidelines for conducting health technology assessment (HTA). Agency for health technology assessment https://tools.ispor.org/PEguidelines/source/Poland_Guidelines-for-Conducting-HTA_English-Version.pdf (2009) Accessed 5 May 2021

Australian departament of health. Guidelines for preparing submissions to the pharmaceutical benefits advisory commintee (PBAC). Departament of Health https://pbac.pbs.gov.au (2016) Accessed 15 May 2021

Neyt, M., Cleemput, I., Sande, S.V., Thiry, N.: Belgian guidelines for budget impact analyses. Acta. Clin. Belg. 70, 175–180 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1179/2295333714y.0000000118

National institute for health and care excellence. Guide to methods of technology appraisal 2013. NICE www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9 (2013) Accessed 15 May 2021

Neumann, P.J., Greenberg, D., Olchanski, N.V., Stone, P.W., Rosen, A.B.: Growth and quality of the cost-utility literature, 1976–2001. Value. Health. 8, 3–9 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04010.x

Edmonds, P., Hart, S., Gao, W., Vivat, B., Burman, R., Silber, E., Higginson, I.J.: Palliative care for people severely affected by multiple sclerosis: Evaluation of a novel palliative care service. Mult. Scler. J. 16, 627–636 (2010)

Martindale-Adams, J., Zuber, J., Levin, M., Burns, R., Graney, M., Nichols, L.O.: Integrating caregiver support into multiple sclerosis care. Multiple. Scler. Int (2020). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3436726

ASPE (Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation). National Research Summit on Care, Services and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers: Final Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//181216/FinalReport.pdf (2018) Accessed 29 Jan 2022

Schulz, R., Eden, J., Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults, Board on Health Care Services, Health and Medicine Division, & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (eds.): Families Caring for an Aging America. National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC) (2016)

Tanielian, T., Bouskill, K.E., Ramchand, R., Friedman, E.M., Trail, T.E., Clague, A.: Improving Support for America’s Hidden Heroes: A Military Caregiver Research Blueprint Santa Monica. CA, USA (2017)

Brown, J.W.L., Coles, A., Horakova, D., Havrdova, E., Izquierdo, G., Prat, A., Girard, M., Duquette, P., Trojano, M., Lugaresi, A., Bergamaschi, R., Grammond, P., Alroughani, R., Hupperts, R., McCombe, P., Van Pesch, V., Sola, P., Ferraro, D., Grand’Maison, F., Terzi, M., Lechner-Scott, J., Flechter, S., Slee, M., Shaygannejad, V., Pucci, E., Granella, F., Jokubaitis, V., Willis, M., Rice, C., Scolding, N., Wilkins, A., Pearson, O.R., Ziemssen, T., Hutchinson, M., Harding, K., Jones, J., McGuigan, C., Butzkueven, H., Kalincik, T., Robertson, N.: Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA 321, 175–187 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.20588

Ontaneda, D., Tallantyre, E., Kalincik, T., Planchon, S.M., Evangelou, N.: Early highly effective versus escalation treatment approaches in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Lancet. Neurol. 18, 973–980 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30151-6

Eichhorst, W., Marx, P., Wehner, C.: Labor market reforms in Europe: towards more flexicure labor markets? J. Labour. Market. Res. 51, 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-017-0231-7

Mueller, M., Bourke, E. and Morgan, D.: Assessing the comparability of long-term care spending estimates under the Joint Health Accounts questionnaire. Technical report, OECD. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/LTC-Spending-Estimates-underthe-Joint-Health-Accounts-Questionnaire.pdf (2020) Accessed 21 Jan 2022

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 779312.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Daugbjerg, S., Peña-Longobardo, L.M. et al. Does the inclusion of societal costs change the economic evaluations recommendations? A systematic review for multiple sclerosis disease. Eur J Health Econ 24, 247–277 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01471-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01471-9

Keywords

- Economic evaluation

- Health technology assessment

- Informal care

- Productivity losses

- Multiple sclerosis

- Societal perspective

- Social costs

- Cost-effectiveness

- Cost-utility