Abstract

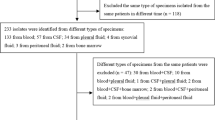

Little is known about occult bacteremia (OB) in Spain following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine (PCV13). Our aim was to describe the microbiologic characteristics and management of OB among children aged 3–36 months in Spain in the era of PCV13. Data were obtained from a multicenter registry of positive blood cultures collected at 22 Spanish emergency departments (ED). Positive blood cultures performed on patients aged 3–36 months from 2011 to 2015 were retrospectively identified. Immunocompetent infants with a final diagnosis of OB were included. Non-well-appearing patients and patients with fever > 72 h were excluded. We analyzed 67 cases (median age 12.5 months [IQR 8.7–19.4]). Thirty-seven (54.4%) had received ≥ 1 dose of PCV. Overall, 47 (70.1%) were initially managed as outpatients (38.3% of them with antibiotic treatment). Phone contact was established with 43 (91.5%) of them after receiving the blood culture result and 11 (23.4%) were hospitalized with parenteral antibiotic. All patients did well. Streptococcus pneumoniae was isolated in 79.1% of the patients (42.2% of the isolated serotypes were included in the PCV13). S. pneumoniae remains the first cause of OB in patients attended in the ED, mainly with non-PCV13 serotypes. Most of the patients with OB were initially managed as outpatients with no adverse outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

21 June 2018

The names of the three authors (Borja Gómez, Santiago Mintegi, and Juan J. García-García) were inadvertently removed during the production of the original article. The names of the authors are correctly captured here.

References

Stoll ML, Rubin LG (2004) Incidence of occult bacteraemia among highly febrile young children in the era of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a study from a children’s hospital emergency department and urgent care center. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 158:671–675

Sard B, Bailey MC, Vinci R (2006) An analysis of pediatric blood cultures in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era in a community hospital emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 22:295–300

Waddle E, Jhaveri R (2009) Outcomes of febrile children without localising signs after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Arch Dis Child 94:144–147. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.130583

Wilkinson M, Bulloch B, Smith M (2009) Prevalence of occult bacteraemia in children aged 3 to 36 months presenting to the emergency department with fever in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Acad Emerg Med 16:220–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00328

Bressan S, Berlese P, Mion T et al (2012) Bacteraemia in feverish children presenting to the emergency department: a retrospective study and literature review. Acta Paediatr 101:271–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02478

Lee GM, Fleisher GR, Harper MB (2001) Management of febrile children in the age of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Pediatrics 108:835–844

Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR et al (1993) Practice guideline for the management of children and infants 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Ann Emerg Med 22:1198–1210

Zeretzke CM, McIntosh MS, Kalynych CJ et al (2012) Reduced use of occult bacteremia blood screens by emergency medicine physicians using immunization registry for children presenting with fever without a source. Pediatr Emerg Care 28:640–645. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e31825cfd3e

Simon AE, Lukacs SL, Mendola P (2011) Emergency department laboratory evaluations of fever without source in children aged 3 to 36 months. Pediatrics 128:e1368–e1375. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3855

Baraff LJ (2008) Management of infants and young children with fever without source. Pediatr Ann 37:673–679

NICE (2013) Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. CG160. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg160. Accessed 20 Sep 2017

Weil-Olivier C, van der Linden M, de Schutter I et al (2012) Prevention of pneumococcal diseases in the post-seven valent vaccine era: a European perspective. BMC Infect Dis 12:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-207

Sharma D, Baughman W, Holst A et al (2013) Pneumococcal carriage and invasive disease in children before introduction of the 13-valent conjugate vaccine: comparison with the era before 7-valent conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 32:e45–e53. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e3182788fdd

Link-Gelles R, Taylor T, Moore MR, Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team (2013) Forecasting invasive pneumococcal disease trends after the introduction of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the United States, 2010-2020. Vaccine 31:2572–2577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.049

Moore CE, Paul J, Foster D, Oxford Invasive Pneumococcal Surveillance Group et al (2014) Reduction of invasive pneumococcal disease 3 years after the introduction of the 13-valent conjugate vaccine in the Oxfordshire region of England. J Infect Dis 210:1001–1011. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu213

Moore MR, Link-Gelles R, Schaffner W et al (2015) Effect of use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children on invasive pneumococcal disease in children and adults in the USA: analysis of multisite, population-based surveillance. Lancet Infect Dis 15:301–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71081-3

Benito-Fernández J, Mintegi S, Pocheville-Gurutzeta I et al (2010) Pneumococcal bacteraemia in febrile infants presenting to the emergency department 8 years after the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the Basque Country of Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J 29:1142–1144. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e3181eaf89a

Hernandez-Bou S, Trenchs V, Batlle A et al (2015) Occult bacteraemia is uncommon in febrile infants who appear well, and close clinical follow-up is more appropriate than blood tests. Acta Paediatr 104:e76–e81. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12852

Gomez B, Hernandez-Bou S, Garcia-Garcia JJ, Mintegi S, Bacteraemia Study Working Group of the Infectious Diseases Working Group of the Spanish Society of Pediatric Emergencies (SEUP) (2015) Bacteremia in previously healthy children in emergency departments: clinical and microbiological characteristics and outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34:453–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-014-2247-z

Dieckmann RA, Brownstein D, Gausche-Hill M (2010) The pediatric assessment triangle: a novel approach for the rapid evaluation of children. Pediatr Emerg Care 26:312–315. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181d6db37

Herz AM, Greenhow TL, Alcantara J et al (2006) Changing epidemiology of outpatient bacteraemia in 3 to 36 month-old children after the introduction of the heptavalent-conjugate pneumococcal vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 25:293–300

Rudinsky SL, Carstairs KL, Reardon JM et al (2009) Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Acad Emerg Med 16:585–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00444

Ribitzky-Eisner H, Minuhin Y, Greenberg D et al (2016) Epidemiologic and microbiologic characteristics of occult bacteremia among febrile children in southern Israel, before and after initiation of the routine antipneumococcal immunization (2005-2012). Pediatr Neonatol 57:378–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.10.004

Antachopoulus C, Tsolia MN, Tzanakaki G et al (2014) Parapneumonic pleural effusions caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 3 in children immunized with 13-valent conjugated pneumococcal vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33:81–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000000041

Moraga-Llop F, García-García JJ, Díaz-Conradi A et al (2016) Vaccine failures in patients properly vaccinated with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Catalonia, a region with low vaccination coverage. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35:460–463. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001041

Selva L, Ciruela P, Esteva C et al (2012) Serotype 3 is a common serotype causing invasive pneumococcal disease in children less than 5 years old, as identified by real-time PCR. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:1487–1495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-011-1468-7

Leibovitz E, David N, Ribitzky-Eisner H et al (2016) The epidemiologic, microbiologic and clinical picture of bacteremia among febrile infants and young children managed as outpatients at the emergency room, before and after initiation of the routine anti-pneumococcal immunization. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:E723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070723

Manzano S, Bailey B, Gervaix A, Cousineau J, Delvin E, Girodias J (2011) Markers for bacterial infection in children with fever without source. Arch Dis Child 96:440–446. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2010.203760

Mintegi S, Benito J, Sánchez J et al (2009) Predictors of occult bacteraemia in young febrile children in the era of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine. Eur J Emerg Med 16:199–205

Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T et al (2011) Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systematic review. BMJ 342:d3082. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d3082

Pelton SI, Loughlin AM, Marchant CD (2004) Seven valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine immunization in two Boston communities. Changes in serotypes and antimicrobial susceptibility among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates. Pediatr Infect Dis J 23:1015–1022

Bachur R, Harper MB (2000) Reevaluation of outpatients with Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia. Pediatrics 105:502–509

Claudius I, Baraff LJ (2010) Pediatric emergencies associated with fever. Emerg Med Clin North Am 28:67–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2009.09.002

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the members of the Bacteraemia Study Working Group of the Infectious Diseases Working Group of the Spanish Society of Pediatric Emergencies. The 22 participating centers and their researchers were as follows:

Hospital Sant Joan de Déu Barcelona (Carla Pascual), Hospital Universitari Vall D’Hebrón (Nuria Worner, Susana Melendo), Niño Jesús Children’s University Hospital (Mercedes de la Torre, Mercedes Alonso), Cruces University Hospital (Iker Gangoiti, Usune González), Canaries University Hospital Maternity Ward (Sara García), Son Espases University Hospital (Carmen Pérez, Enrique Ruiz de Gopegui), Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Sofía Mesa, María Ángeles Orellana), Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital (María Ángeles García, Peña Gómez), Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí. Hospital de Sabadell. Institut Universitari Parc Taulí - UAB (Laura Marzo, Dionisia Fontanals), Basurto University Hospital (María Landa, José Luis Díaz de Tuesta), Cabueñes Hospital (Ramón Fernández, Begoña Fernández), Althaia. Xarxa Assistencial Universitària de Manresa (Zulema Lobato, Montse Morta), Mendaro Hospital (Laura Herero, Yosune Mendiola), Hospital Moncloa (Juana Barja, Rodolfo Luján), Alto Deba General Hospital (Goizalde López, Ainara Rodríguez), Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (José Rodríguez, Ana Blázquez), Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía (Alfredo Tagarro, Esteban Aznar), Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus (Neus Rius), Hospital General de Catalunya (Esther Oliva), Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (Francisca Aguilar, Angela Bello), Hospital Universitario Río Hortega (María Nathalie Campo, Juncal Mena), Hospital del Tajo (Clara García-Bermejo).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Basque Country, under whose auspices the coordinating institution operates. Approval for the study and for data sharing with the coordinating institution and with the centralized data center was granted by the institutional review board at each participating institution.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: The names of the three authors were inadvertently removed during the production of the original article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernández-Bou, S., Gómez, B., Mintegi, S. et al. Occult bacteremia etiology following the introduction of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a multicenter study in Spain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 37, 1449–1455 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3270-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3270-2