Abstract

This paper reexamines the Barro growth model in a context of interdependent preferences with consumption externality. Agents care about both consumption and social status, which is determined by their relative consumption in society. The results underline the individuals’ preferences for status as a key role in explaining long term growth and welfare. In particular, a higher growth rate may correspond to a lower social welfare if increment in growth is explained by status-seeking accompanied by the keeping up with the Joneses. Furthermore, we discuss two public financing systems from the viewpoint of growth and welfare. If lump-sum tax always implies a higher growth rate, income tax may perform better in terms of welfare when government size becomes sufficiently large.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The government size is defined as the ratio of public spending to income.

In a model with endogenous leisure, Dupor and Liu (2003) introduced the notion of keeping up with (or running away from) the Joneses when the marginal rate of substitution between leisure and individual consumption increases (decreases) with respect to the average consumption level.

For example, Alvarez-Cuadrado et al. (2015) estimated the importance of the interdependence of preferences and habit persistence. The results suggest that households’ preferences derive almost 25% of their consumption services from comparison between their consumption and that of their neighbours, and around 35% from comparison between their current and past consumption. This implies that around 60% of individual satisfaction is from relative consumption.

Using German panel (GSOEP) spanning the years 1984–2001 and considering life satisfaction as a proxy of individual utility, Vendrik and Woltjer (2007) found the concavity of individual utility in relative income.

As the utility function is concave in c and the capital accumulation function is concave in k, then the first-order conditions of the Hamiltonian problem are also sufficient (Mangasarian 1966).

However, the social planner does not necessarily need to incorporate status concerns in her social objective. A non-welfarist social planner can calculate the optimal growth on the basis of another set of preferences, ignoring status concerns. In this case, individuals may attach a weight \(s > 0\) to social status while it is considered as null by the non-welfarist social planner. The optimal growth rate is that of the status externality free-centralized economy as shown in Rauscher (1997), Corneo and Jeanne (1997).

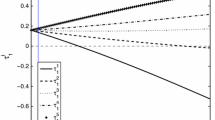

Combining (21) with (22), we can rewrite the optimal growth rate as \(\gamma ^{o} = \frac{\sigma }{1 - s + s \sigma } \left[ (1-\tau ) A^{\frac{1}{1- \alpha }}\tau ^{\frac{\alpha }{1- \alpha }} - \rho - \delta \right] \). The FOC for a maximum value of \(\gamma ^{o}\) is \(\frac{\partial \gamma ^{o}}{ \partial \tau } = \frac{\sigma A^{\frac{1}{1- \alpha }}}{1 - s + s \sigma } \left[ -\tau ^{\frac{\alpha }{1- \alpha }} + \frac{\alpha }{1-\alpha }(1-\tau ) \tau ^{\frac{\alpha }{1- \alpha }-1} \right] = 0\). It is satisfied when \({\hat{\tau }} = \alpha .\) Notice that the second derivative of \(\gamma ^{o}\) with respect to \(\tau \) is negative for \(\tau = {\hat{\tau }}\). This confirms that \({\hat{\tau }} = \alpha \) is the government size maximizing the optimal growth rate.

References

Alvarez-Cuadrado F, Casado JM, Labeaga JM (2015) Envy and habits: panel data estimates of interdependent preferences. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 0305–9049. https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12111

Barro RJ (1990) Government spending in a simple model of endogenous growth. J Polit Econ 98:S103–S125

Brekke K-A, Howarth RB (2002) Status, growth and the environment: goods as symbols in applied welfare economics. Edward Elgar, Northampton

Clark A, Frijters P, Shields M (2008) Relative income, happiness and utility: an explanations for easterlin paradox and other puzzles. J Econ Lit 46:95–144

Corneo G, Jeanne O (1997) Relative wealth effects and the optimality of growth. Econ Lett 54:87–92

Corneo G, Jeanne O (2001) On the relative-wealth effects and long-run growth. Res Econ 55:349–358

Duesenberry JS (1949) Income, saving and the theory of consumer behaviour. Havard University Press, Cambridge

Dupor B, Liu W-F (2003) Jealousy and equilibrium overconsumption. Am Econ Rev 93(1):423–428

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A (2005) Income and well-being : an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. J Publ Econ 89:997–1019

Fisher WH, Hof FX (2000) Relative consumption, economic growth and taxation. J Econ (Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie) 73:241–262

Frijters P, Shields M, Haisken-Deneuw J (2004) Money does matter! evidence from increasing real incomes in east germany following reunification. Am Econ Rev 94:730–741

Galí J (1994) Keeping up with the Joneses: consumption externalities, portfolio choice, and asset prices. J Money Credit Bank 26(1):1–8

Glomm G, Ravikumar B (1994) Growth-inequality trade-offs in a model with public sector R-D. Can J Econ 27:485–493

Gómez M (2006) Optimal consumption taxation in a model of endogenous growth with external habit formation. Econ Lett 93:427–435

Johansson-Stenman O, Carlsson F, Daruvala D (2002) Measuring hypothetical grandparents, preferences for equality and relative standing. Econ J 112:362–83

Lau S-HP (1995) Welfare-maximizing vs. growth-maximizing shares of government investment and consumption. Econ Lett 47(3–4):351–359

Liu W-F, Turnovsky SJ (2005) Consumption externalities, production externalities and long-run macroeconomic efficiency. J Publ Econ 89:1097–1129

Long NV, Shimomura K (2004) Relative wealth, status seeking and catching-up. J Econ Behav Organ 53:529–542

Mangasarian OL (1966) Sufficient conditions for the optimal control of nonlinear systems. SIAM J Control 4:139–152

Marrero GA, Novales A (2005) Growth and welfare: distorting versus non-distorting taxes. J Macroecon 27:403–433

McBride M (2001) Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. J Econ Behav Organ 45:251–278

Ng YK (2003) From preferences to happiness: towards a more complete welfare economics. Soc Choice Welfare 20:307–350

Nguyen-Van P, Pham TKC (2013) Endogenous fiscal policies, environmental quality, and status-seeking behavior. Ecol Econ 88:32–40

Pham TKC (2005) Economic growth and status-seeking through personal wealth. Eur J Polit Econ 21:407–427

Rauscher M (1997) Conspicuous consumption, economic growth and taxation. J Econ (Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie) 66:35–42

Turnovsky SJ, Monteiro G (2007) Consumption externalities, production externalities and efficient capital accumulation under time non-separable preferences. Eur Econ Rev 51:479–504

Vendrik M, Woltjer GB (2007) Hapiness and loss aversion: is utility concave or convex in relative income? J Publ Econ 91:1423–1448

Wendner R (2003) Status, environmental externality, and optimal tax programs. Econ Bull 5:1–10

Wendner R (2010) Growth and keeping up with the Joneses. Macroecon Dyn 14:176–199

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am thankful to the two anonymous referees of this journal and Cuong Le-Van for their useful comments. All remaining errors are mine.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pham, T.K.C. Keeping up with or running away from the Joneses: the Barro model revisited. J Econ 126, 179–192 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-018-0624-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-018-0624-2

Keywords

- Income tax

- Lump-sum tax

- Keeping up with the Joneses

- Public spending

- Running away from the Joneses

- Status-seeking