Abstract

Introduction

Previous studies demonstrated an unfavorable psychological outcome after treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms despite an objectively favorable clinical and radiological outcome. The current study was therefore designed to analyze the psychiatric vulnerability of this specific patient collective.

Materials and methods

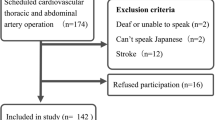

Patients treated for a WHO grade I meningioma and incidental intracranial aneurysms in two German neurosurgical centers between 2007 and 2013 were screened for exclusion criteria including malignant/chronic diseases, recurrence of the tumor/aneurysm after more than 12 months and focal neurological deficits, among others. Seventy-five meningioma patients (M) and 56 incidental aneurysm patients (iA) met the inclusion criteria. The past medical psychiatric history, post-morbid personality characters and coping strategies were determined by questionnaires mailed to the patients in a printed version (Brief COPE, Big Five Personality Test).

Results

Fifty-eight M and 45 iA patients returned the questionnaires. Patients with iA demonstrated significantly higher pre-interventional rates of depressive episodes (p = 0.002) and psychological supervision (p = 0.038). These findings were especially aggravated in iA patients who received their cranial imaging for unspecific symptoms such as dizziness, headaches or tinnitus (n = 33, history of depressions: 39.4 %; previous psychological supervision: 33.3 %). Furthermore, the analysis of the Big Five personality traits revealed remarkably elevated neuroticism scores in the iA collective.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrates an increased rate of positive pre-interventional psychiatric histories in the iA collective. Although those patients represent only a small subgroup, they still may play an important role concerning the overall outcome after iA treatment. Early detection and psychological support in this subgroup might help to improve the overall outcome. Further studies are needed to evaluate the influence of this new aspect on the multifactorial etiology of unfavorable psychiatric outcome after treatment of iA.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amoyal NR, Mason ST, Gould NF, Corry N, Mahfouz S, Barkey A, Fauerbach JA (2011) Measuring coping behavior in patients with major burn injuries: a psychometric evaluation of the BCOPE. J Burn Care Res 32:392–398

Bonares MJ, de Oliveira Manoel AL, Macdonald RL, Schweizer TA (2014) Behavioral profile of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 1:220–232

Brilstra EH, Rinkel GJ, van der Graaf Y, Sluzewski M, Groen RJ, Lo RT, Tulleken CA (2004) Quality of life after treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms by neurosurgical clipping or by embolisation with coils. A prospective, observational study. Cerebrovasc Dis 17:44–52

Brinjikji W, Rabinstein AA, Nasr DM, Lanzino G, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ (2011) Better outcomes with treatment by coiling relative to clipping of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the United States, 2001–2008. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 32:1071–1075

Brown RD (2010) Unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Semin Neurol 30:537–544

Buijs JE, Greebe P, Rinkel GJ (2012) Quality of life, anxiety, and depression in patients with an unruptured intracranial aneurysm with or without aneurysm occlusion. Neurosurgery 70:868–872

Carver CS (1997) You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 4:92–100

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK (1989) Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 56:267–283

Caspi ARB, Shiner RL (2005) Personality development: stability and change. Annu Rev Psychol 56:453–484

Cooper C, Katona C, Livingston G (2008) Validity and reliability of the brief COPE in carers of people with dementia: the LASER-AD Study. J Nerv Ment Dis 196:838–843

Costa PT, Bagby RM, Herbst JH, McCrae RR (2005) Personality self-reports are concurrently reliable and valid during acute depressive episodes. J Affect Disord 89:45–55

DeYoung CG, Quilty LC, Peterson JB (2007) Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. J Pers Soc Psychol 93:880–893

Etminan N, Beseoglu K, Steiger HJ, Hänggi D (2011) The impact of hypertension and nicotine on the size of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 82:4–7

Fogelholm R, Hernesniemi J, Vapalahti M (1993) Impact of early surgery on outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. A population-based study. Stroke 24:1649–1654

Goebel S, Mehdorn HM (2013) Development of anxiety and depression in patients with benign intracranial meningiomas: a prospective long-term study. Support Care Cancer 21:1365–1372

Goldberg L (1990) An alternative “description of personality”: the big-five factor structure. J Pers Soc Psychol 59:1216–1229

Griens AM, Jonker K, Spinhoven P, Blom MB (2002) The influence of depressive state features on trait measurement. J Affect Disord 70:95–99

Hackett ML, Anderson CS (2000) Health outcomes 1 year after subarachnoid hemorrhage: an international population-based study. The Australian Cooperative Research on Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Study Group. Neurology 55:658–662

Hettema JM, Neale MC, Myers JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS (2006) A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders. Am J Psychiatry 163:857–864

Hop JW, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, van Gijn J (1997) Case-fatality rates and functional outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review. Stroke 28:660–664

Horikoshi T, Akiyama I, Yamagata Z, Nukui H (2002) Retrospective analysis of the prevalence of asymptomatic cerebral aneurysm in 4518 patients undergoing magnetic resonance angiography—when does cerebral aneurysm develop? Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 42:105–112

Hwang JS, Hyun MK, Lee HJ, Choi JE, Kim JH, Lee NR, Kwon JW, Lee E (2012) Endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysm: a systematic review. BMC Neurol 12:99

Jeronimus BF, Riese H, Sanderman R, Ormel J (2014) Mutual reinforcement between neuroticism and life experiences: a five-wave, 16-year study to test reciprocal causation. J Pers Soc Psychol 107:751–764

John OP, Srivastava S (1999) The big-five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin L, John OP (eds) Handbook of personality: theory and research. Guilford, New York

Jylhä P, Melartin T, Rytsälä H, Isometsä E (2009) Neuroticism, introversion, and major depressive disorder–traits, states, or scars? Depress Anxiety 26:325–334

Karsten J, Penninx BW, Riese H, Ormel J, Nolen WA, Hartman CA (2012) The state effect of depressive and anxiety disorders on big five personality traits. J Psychiatr Res 46:644–650

Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ (1993) A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:853–862

Koch-Institut R (2012) Daten und Fakten: Ergebnisse der Studie »Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2010«. In: Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes http://www.rki.de/gbe. Accessed 16 Apr 2015

Koorevaar AM, Comijs HC, Dhondt AD, van Marwijk HW, van der Mast RC, Naarding P, Oude Voshaar RC, Stek ML (2013) Big Five personality and depression diagnosis, severity and age of onset in older adults. J Affect Disord 151:178–185

Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D (2010) Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 136:768–821

McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr (1987) Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J Pers Soc Psychol 52:81–90

McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr, Pedroso de Lima M, Simões A, Ostendorf F, Angleitner A, Marusić I, Bratko D, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Chae JH, Piedmont RL (1999) Age differences in personality across the adult life span: parallels in five cultures. Dev Psychol 35:466–477

Ormel J, Jeronimus BF, Kotov R, Riese H, Bos EH, Hankin B, Rosmalen JG, Oldehinkel AJ (2013) Neuroticism and common mental disorders: meaning and utility of a complex relationship. Clin Psychol Rev 33:686–697

Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, Vollebergh W (2004) Vulnerability before, during, and after a major depressive episode: a 3-wave population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:990–996

Otawara YOK, Ogawa A, Yamadate K (2005) Cognitive function before and after surgery in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysm. Stroke 36:142–143

Raaymakers TW (2000) Functional outcome and quality of life after angiography and operation for unruptured intracranial aneurysms. On behalf of the MARS Study Group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 68:571–576

Radwan GN, Loffredo CA, Abdelaziz H, Amr S (2014) Associations of depression and neuroticism with smoking behavior and motives among men in rural Qalyubia (Egypt). J Egypt Public Health Assoc 89:16–21

Rinkel GJ, Djibuti M, Algra A, van Gijn J (1998) Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review. Stroke 29:251–256

Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W (2006) Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull 132:1–25

Satow L (2012) Big-Five-Persönlichkeitstest (B5T): Testmanual und Normen http://www.drsatow.de. Accessed 16 Apr 2015

Solheim O, Eloqayli H, Muller TB, Unsgaard G (2006) Quality of life after treatment for incidental, unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 148:821–830, discussion 830

Srivastava S, John OP, Gosling SD, Potter J (2003) Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: set like plaster or persistent change? J Pers Soc Psychol 84:1041–1053

Thompson ER (2008) Development and validation of an international English big-five mini-markers. Personal Individ Differ 45:542–548

Towgood K, Ogden JA, Mee E (2005) Psychosocial effects of harboring an untreated unruptured intracranial aneurysm. Neurosurgery 57:858–856

Tuffiash E, Tamargo R, Hillis AE (2003) Craniotomy for treatment of unruptured aneurysms is not associated with long-term cognitive dysfunction. Stroke 34:2195–2199

Tuncay T, Musabak I, Gok DE, Kutlu M (2008) The relationship between anxiety, coping strategies and characteristics of patients with diabetes. Health Qual Life Outcomes 6

Vindlacheruvu RR, Mendelow AD, Mitchell P (2005) Risk-benefit analysis of the treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:234–239

Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB (2010) Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol 99:307–314

Yamashiro S, Nishi T, Koga K, Goto T, Kaji M, Muta D, Kuratsu J, Fujioka S (2007) Improvement of quality of life in patients surgically treated for asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78:497–500

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements) or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comment

Although this relatively small follow-up study carried out in highly selected patients with subgroup analyses and multiple significance testing is vulnerable to bias, it nevertheless adds to the growing but still weak knowledge concerning the possible psychiatric comorbidity in patients with intracranial aneurysms. Neuroticism is probably a risk factor for most incidental intracranial findings. Without concern about and attention to often unspecific symptoms, patients do not seek medical attention and are not diagnosed. Furthermore, aneurysms may be incidentally discovered, but they do not develop randomly. Lifestyle-related factors such as smoking and hypertension are strong risk factors and are probably associated with psychological vulnerability on a group level. Also, when considering prophylactic treatment surgeons may at times perhaps favor active interventions in overly anxious or vulnerable patients to offer relief or help them move on. In summary, our aneurysm patients are not the average Joe or Jane, and this may affect treatment results for soft outcomes.

Ole Solheim

Trondheim,Norway

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wenz, H., Wenz, R., Ehrlich, G. et al. Patient characteristics support unfavorable psychiatric outcome after treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochir 157, 1135–1145 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-015-2451-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-015-2451-3