Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection on surgical outcomes after appendectomy.

Methods

Data on patients who underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis between 2010 and 2020 at our hospital were investigated retrospectively. The patients were classified into HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups using propensity score-matching (PSM) analysis, adjusting for the five reported risk factors for postoperative complications: age, sex, Blumberg’s sign, C-reactive protein level, and white blood cell count. We compared the postoperative outcomes of the two groups. HIV infection parameters, including the number and proportion of CD4 + lymphocytes and the HIV-RNA levels were also compared before and after appendectomy in the HIV-positive patients.

Results

Among 636 patients enrolled, 42 were HIV-positive and 594 were HIV-negative. Postoperative complications occurred in five HIV-positive patients and eight HIV-negative patients, with no significant difference in the incidence (p = 0.405) or severity of any complication (p = 0.655) between the groups. HIV infection was well-controlled preoperatively using antiretroviral therapy (83.3%). There was no deterioration in parameters and no changes in the postoperative treatment in any of the HIV-positive patients.

Conclusion

Advances in antiviral drugs have made appendectomy a safe and feasible procedure for HIV-positive patients, with similar postoperative complication risks to HIV-negative patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of patients living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is increasing, in line with advances in antiretroviral therapy [1]. As this patient population grows, more such patients will undergo surgery. Patients with HIV are generally immunocompromised, and HIV infection is regarded as a perioperative risk associated with higher morbidity, more severe postoperative complications, and longer hospital stays [2,3,4,5]. Thus, surgeons must assess HIV-positive [HIV (+)] patients carefully to predict their postoperative risk and evaluate the benefit–risk balance of surgery.

Appendicitis is the most common abdominal emergency worldwide [6], so the number of appendectomies performed on HIV (+) patients is expected to increase [7]. However, the surgical outcomes of HIV (+) patients who undergo appendectomy have been poorly described in the literature and few studies have investigated the impact of surgery on subsequent HIV treatment. This study evaluates the impact of HIV infection on postoperative outcomes following appendectomy for acute appendicitis by comparing data from HIV (+) and HIV-negative [HIV (−)] patients, using propensity score-matching (PSM) analysis.

Methods

Patients

We reviewed the medical records, retrospectively, of consecutive patients who underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis between January 2010 and December 2020. Surgeons diagnosed acute appendicitis based on the physical examination of patients presenting with signs and symptoms including vomiting or nausea, pain in the right lower quadrant, rebound tenderness or muscular defense; laboratory data [C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and white blood cell (WBC) count]; and imaging findings, including enlargement of the appendix, dirty-fat signs around the appendix, hardened feces, or abscess. Patients underwent emergency appendectomy at the Department of Surgery of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine. Data on baseline patient characteristics (demographics, preoperative risk factors, and comorbidities), types of antiretroviral drugs, operative records, and postoperative outcomes from the retrieved hospital medical records were obtained and entered in a database for analysis. This study was approved by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine Research Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board (Approval no. NCGM-G-004099–00) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 1983. Informed consent was obtained on the website with an option to opt out. Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from the study.

Treatment strategy for appendicitis

Catarrhal appendicitis was treated conservatively, with antibiotics, whereas phlegmonous or more advanced appendicitis was treated surgically when the patient's general condition allowed. Surgery was always indicated for perforation or when there was a high possibility of perforation, including appendicitis with fecal calculus or a swollen appendix greater than 10 mm. In the case of obvious abscess formation, conservative antibiotic therapy preceded interval appendectomy, which was performed a few months later. Laparoscopic surgery was the first choice, but the open approach was chosen for patients with impaired cardiopulmonary function, and when laparoscopic instruments were not available in emergency situations. The treatment strategy was the same for HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients.

Variables studied

The patients were divided into HIV (+) and HIV (−) groups for comparison. Preoperative variables included age, sex, presence of Blumberg’s sign, and blood test values for inflammation, such as CRP levels and WBC count. The surgical parameters included the surgical approach (laparoscopic surgery or laparotomy), operative time (minutes), and blood loss (mL). Postoperative morbidity was evaluated according to the Clavien–Dindo (C–D) classification within 30 days after surgery. The C–D classification, which is used for general surgery, assesses the validated and simple classification of postoperative complications from I to V. Grade I is any deviation from the normal postoperative course without any treatment; grade II requires pharmacological treatment; grade III requires surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention; grade IV is life-threatening and requires intensive care unit management; and grade V indicates death. Complications of C–D grade ≥ III were defined as severe [8].

Human immunodeficiency virus infection parameters included the number and proportion of CD4 + lymphocytes and the level of HIV-RNA. The HIV-RNA levels were detected only in absolute amounts at or above 40. Patients < 40 years of age were divided into three groups (undetected, < 20, and < 40). The average value was calculated as > 40.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation or as median values (range) and were compared using Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. PSM analysis was used to develop a matched patient group. The propensity model was developed using a logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, presence of Blumberg’s sign, CRP, and WBC, which are reported risk factors for postoperative complications after appendectomy [9,10,11,12]. A 1:1 match without replacement was performed using logit (propensity score) through the nearest available matching, with the caliper set at 0.05. After the PSM, continuous and categorical variables were compared using the paired t test and McNemar’s test, respectively. Parameters related to HIV infection were compared before and after the surgery. Continuous and categorical variables of the indicators of HIV were also assessed using the paired t test and McNemar’s test. Statistical analyses were performed using the JMP® Pro software (version 15; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

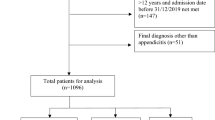

A total of 636 patients were enrolled (392 male patients and 244 female patients, with a median (range) age of 45 (4–91) years). Before the PSM, there were 42 HIV (+) and 594 HIV (−) patients, with significant differences in sex, Blumberg’s sign, and WBC count between the groups. After PSM, the 42 HIV (+) patients (the HIV (+) group) and 42 matched patients who were HIV (−) (the HIV (−) group) were the subjects of this analysis. Table 1 summarizes the patients’ characteristics before and after PSM. The patient demographics were comparable after PSM.

Surgical parameters and postoperative outcomes

Table 2 summarizes the surgical parameters and postoperative outcomes of the patients after PSM. All the patients in both groups underwent emergency surgery. The emergency surgery was changed in some patients because of failure after the initiation of antibiotic treatment. The surgical approach was open in 18 (21.4%) patients and laparoscopic in 66 (78.6%) patients, without a significant difference between the groups. Postoperative complications developed in 13 patients: 5 from the HIV (+) group and 8 from the HIV (−) group. C–D ≥ IIIa complications developed in two patients from the HIV (+) group (acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and abscess formation in one each), and in three patients from the HIV (−) group (ARDS, abscess formation, and paralytic ileus in one each). The two patients with ARDS were intubated and required intensive care for a few days. The patients with abscess formation were treated with percutaneous computed tomography-guided drainage, and the patients with paralytic ileus were treated with an ileus tube. The incidence of each complication was not significantly different between the groups. There were no significant differences in other postoperative outcomes, including blood loss (p = 0.852), operation time (p = 0.112), or hospitalization (p = 0.136). There was no mortality in either group.

Effect on HIV treatment

HIV had been diagnosed prior to surgery in 40 patients, 35 of whom were treated preoperatively with anti-retroviral therapy (ART), and 5 of whom were on treatment-free follow-up. HIV infection was diagnosed at the onset of appendicitis in the other two patients. The route of infection was homosexual transmission in 29 (69.0%) patients, bisexual transmission in six (14.3%) patients, heterosexual transmission in three (7.2%) patients, hemophiliac transmission in three (7.2%) patients, and unknown in one (2.4%) patient. Table 3 summarizes the parameters of the HIV (+) patients. There was no incidence of an AIDS-related complex at the time of surgery. The preoperative mean CD4 + lymphocyte count of all the patients was 523 ± 271 cells/μL, and the number of patients with a preoperative HIV-RNA level < 20 copies/ml was 26 (61.9%), indicating that HIV infection was well controlled in our HIV(+) group patients. After appendectomy, a decrease in CD4 + lymphocytes was noted in 16 (38.1%) patients and an increase in HIV-RNA was observed in 10 (23.8%) patients. However, there were no significant differences between these two values before and after appendectomy. Even in the two HIV (+) patients with severe postoperative complications, there was no reduction in the number of CD4 + lymphocytes, and the level of HIV-RNA remained unchanged. From the perspective of preoperative HIV control, there were three patients with a CD4 + lymphocyte count < 200 cells/μL, which has been reportedly associated with a significant increase in postoperative complications [13,14,15]; however, all these patients had a good postoperative course without postoperative complications. There was no deterioration in the control of HIV infection or a requirement to change HIV treatment after appendectomy in any of our patients.

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of HIV infection on postoperative complications following emergency appendectomy. We used PSM analysis to compare HIV (+) and HIV (−) patients based on the reported postoperative risk factors. Our analysis showed no difference in postoperative complications between the groups, suggesting that HIV infection was not associated with morbidity after appendectomy if HIV activity was controlled.

Appendicitis is a common gastrointestinal surgical emergency in HIV (+) patients [2, 4, 16,17,18,19]. While appendectomy is effective, the associated postoperative morbidity and mortality are related to HIV positivity. Smith et al. reported that patients with AIDS who underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis tended to have longer and more expensive hospital admissions and higher rates of postoperative infections [2]. However, in some reports from areas with high rates of HIV infection, such as African countries, early diagnosis of appendicitis and prompt appendectomy in HIV (+) patients were important because delayed diagnosis is associated with high morbidity, severe postoperative complications, and longer hospital stays [4, 5]. Bova et al. also reported that HIV (+) patients with acute appendicitis should not be treated differently from the healthy population, and that morbidity and mortality may be minimized by prompt surgical treatment [17]. However, few reports have compared postoperative results following appendectomy between HIV (+) and (−) patients. The present study compared postoperative complications between HIV (+) and (−) groups using PSM analysis in a hospital, based on HIV treatment in Japan. HIV infection was not associated with postoperative complications or the length of the hospital admission. Our results suggest that appendectomy can be performed safely for appendicitis in HIV (+) patients, as for appendicitis in non-HIV-infected patients.

Patients with HIV are immunocompromised and rely on ART combining multiple antiviral drugs to maintain sufficient immune cell counts; most notably, the CD4 positive T-cell count [20]. Moreover, HIV infection can now be treated with ART to achieve a good treatment course [1]. As HIV infection can be effectively controlled, the number of HIV-infected patients undergoing surgical procedures has increased. Some studies have shown that the postoperative complication rate of patients with well-controlled HIV infection is comparable to that of HIV (−) patients [21,22,23,24]. However, HIV infection is generally considered a surgical risk in terms of higher postoperative complications and longer hospital stays [3]. From the perspective of predicting the postoperative course, some studies have found that a low CD4 + lymphocyte count, especially < 200 cells/μL, was associated with a significant increase in postoperative complications after surgical intervention, including abdominal surgery [14, 15, 25]. Other reports have shown that patients with a high HIV viral load in abdominal gastrointestinal surgery had poor prognoses, although no major perioperative problems were observed [26]. In the present study, the incidence of postoperative complications did not differ between the HIV (+) and (−) groups, most likely because most of the HIV (+) patients were treated with ART and had well-controlled HIV infections. Three patients had a CD4 + lymphocyte count of < 200 cells/μL, but they did not suffer postoperative complications. This study also showed that appendectomy had no significant effect on the postoperative HIV control or treatment regimen, suggesting the safety and effectiveness of appendectomy for HIV (+) patients.

This study has several limitations. First, the relatively small number of patients in this analysis could have weakened the results. Second, as this was a retrospective single-center study, a prospective multicenter large study evaluating each operative procedure is needed to validate our findings. Finally, AIDS did not develop in any of the patients with severe HIV infection in the present study; thus, the impact of appendectomy on appendicitis in such patients was not evaluated. Further studies on patients with varying severity of HIV infection are required to analyze the influence of appendectomy on patients with severe HIV infection.

In conclusion, as HIV infection control has become easier with the advancement of ART, appendectomy is now a safe and feasible procedure for HIV (+) patients, with similar postoperative complication risks as for HIV (−) patients. Appendectomy does not affect the postoperative control of HIV infection, provided the HIV is well controlled preoperatively.

Abbreviations

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- PMS:

-

Propensity score-matching

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- C–D:

-

Clavien–Dindo

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- Lap:

-

Laparoscopy

- SSI:

-

Surgical-site infection

References

Yoshimura K. Current status of HIV/AIDS in the ART era. J Infect Chemother. 2017;23:12–6.

Smith MC, Chung PJ, Constable YC, Boylan MR, Alfonso AE, Sugiyama G. Appendectomy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: not as bad as we once thought. Surgery. 2017;161:1076–82.

Sandler BJ, Davis KA, Schuster KM. Symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients have poorer outcomes following emergency general surgery: a study of the nationwide inpatient sample. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86:479–88.

Giiti GC, Mazigo HD, Heukelbach J, Mahalu W. HIV, appendectomy and postoperative complications at a reference hospital in Northwest Tanzania: cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:1–6.

Sobnach S, Ede C, Der GV, Klopper J, Bhyat A, Kahn D. A study comparing outcomes of appendectomy between HIV-infected and HIV-negative patients. Chirurgia. 2019;114:467–74.

Anderson JE, Bickler SW, Chang DC, Talamini MA. Examining a common disease with unknown etiology: trends in epidemiology and surgical management of appendicitis in California, 1995–2009. World J Surg. 2012;36:2787–94.

Sartelli M, Viale P, Catena F, Ansaloni L, Moore E, Malangoni M, et al. 2013 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:1–29.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Poillucci G, Mortola L, Podda M, Saverio SD, Casula L, Gerardi C, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy vs antibiotic therapy for acute appendicitis: a propensity score-matched analysis from a multicenter cohort study. Updates Surg. 2017;69:531–40.

Kim JY, Kim JW, Park JH, Kim BC, Yoon SN. Early versus late surgical management for complicated appendicitis in adults: a multicenter propensity score matching study. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2019;97:103–11.

Podda M, Poillucci G, Pacella D, Mortola L, Canfora A, Aresu S, et al. Appendectomy versus conservative treatment with antibiotics for patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis: a propensity score–matched analysis of patient-centered outcomes (the ACTUAA prospective multicenter trial). Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:589–98.

Allievi N, Harbi A, Ceresoli M, Montori G, Poiasina E, Coccolini F, et al. Acute appendicitis: still a surgical disease? Results from a propensity score-based outcome analysis of conservative versus surgical management from a prospective database. World J Surg. 2017;41:2697–705.

Bedada AG, Hsiao M, Azzie G. HIV infection: its impact on patients with appendicitis in Botswana. World J Surg. 2019;43:2131–6.

Deneve JL, Shantha JG, Page AJ, Wyrzykowski AD, Rozycki GS, Feliciano DV. CD4 count is predictive of outcome in HIV-positive patients undergoing abdominal operations. The Am J Surg. 2010;200:694–700.

Davison SP, Reisman NR, Pellegrino ED, Larson EE, Dermody M, Hutchison PJ. Perioperative guidelines for elective surgery in the human immunodeficiency virus–positive patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1831–40.

Gigabhoy R, Cheddie S, Singh B. Appendicitis in the HIV era: a South African perspective. Indian J Surg. 2018;80:207–10.

Bova R, Meagher A. Appendicitis in HIV-positive patients. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:337–9.

Masoomi H, Mills SD, Dolich MO, Dang P, Carmichael JC, Nguyen NT, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic and open appendectomy for acute appendicitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am Surg. 2011;77:1372–6.

Kitaoka K, Saito K, Tokuuye K. Significance of CD4+ T-cell count in the management of appendicitis in patients with HIV. Can J Surg. 2015;58:429.

Maartens G, Celum C, Lewin SR. HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. Lancet. 2014;384:258–71.

Okumu G, Makobore P, Kaggwa S, Kambugu A, Galukande M. Effect of emergency major abdominal surgery on CD4 cell count among HIV positive patients in a sub Saharan Africa tertiary hospital—a prospective study. BMC Surg. 2013;13:1–7.

Moodley Y. HIV infection and poor renal outcomes following noncardiac surgery. Turk J Med Sci. 2018;48:46–51.

Yang J, Wei G, He Y, Hua X, Feng S, Zhao Y, et al. Perioperative antiretroviral regimen for HIV/AIDS patients who underwent abdominal surgery. World J Surg. 2020;44:1790–7.

Rajcoomar S, Rajcoomar R, Rafferty M, Jagt DVD, Mokete L, Pietrzak JRT. Good functional outcomes and low infection rates in total hip arthroplasty in HIV-positive patients, provided there is strict compliance with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36:593–9.

ČaČala SR, Mafana E, Thomson S, Amith A. Prevalence of HIV status and CD4 counts in a surgical cohort: their relationship to clinical outcome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:46–51.

Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Klein DB, Follansbee SE, Quesenberry C, Flamm JA, et al. Surgical outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1238–45.

Funding

Grants-in-Aid for Research from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (21A1019 to N.T.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Norimatsu, Y., Ito, K., Takemura, N. et al. Surgical management of appendicitis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positivity: a propensity score-matched analysis in a base hospital for HIV treatment in Japan. Surg Today 53, 1013–1018 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-023-02661-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-023-02661-5