Abstract

Purpose

To study the long-term outcome of revision microdiscectomy after classic microdiscectomy for lumbosacral radicular syndrome (LSRS).

Methods

Eighty-eight of 216 patients (41%) who underwent a revision microdiscectomy between 2007 and 2010 for MRI disc-related LSRS participated in this study. Questionnaires included visual analogue scores (VAS) for leg pain, RDQ, OLBD, RAND-36, and seven-point Likert scores for recovery, leg pain, and back pain. Any further lumbar re-revision operation(s) were recorded.

Results

Mean (SD) age was 59.8 (12.8), and median [IQR] time of follow-up was 10.0 years [9.0–11.0]. A favourable general perceived recovery was reported by 35 patients (40%). A favourable outcome with respect to perceived leg pain was present in 39 patients (45%), and 35 patients (41%) reported a favourable outcome concerning back pain. The median VAS for leg and back pain was worse in the unfavourable group (48.0/100 mm (IQR 16.0–71.0) vs. 3.0/100 mm (IQR 2.0–5.0) and 56.0/100 mm (IQR 27.0–74.0) vs. 4.0/100 mm (IQR 2.0–17.0), respectively; both p < 0.001). Re-revision operation occurred in 31 (35%) patients (24% same level same side); there was no significant difference in the rate of favourable outcome between patients with or without a re-revision operation.

Conclusion

The long-term results after revision microdiscectomy for LSRS show an unfavourable outcome in the majority of patients and a high risk of re-revision microdiscectomy, with similar results. Based on also the disappointing results of alternative treatments, revision microdiscectomy for recurrent LSRS seems to still be a valid treatment. The results of our study may be useful to counsel patients in making appropriate treatment choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sciatica is a radiating pain in an area of the leg typically served by one lumbar or sacral spinal nerve root and is generally caused by a herniated disc. If conservative treatment fails, surgery of the herniated disc is a valid treatment option [1]. Open microdiscectomy is the most widely used operative treatment option for sciatica [2]. In a recent consecutive cohort study, the results of microdiscectomy in terms of long-term good outcome appeared to be inferior compared to those in a randomized controlled trial (66% vs.79%). This difference is possibly explained by more strict patient selection in RCTs [3, 4]. One of the reasons for an unsatisfactory outcome can be a re-herniated disc at the same level and the same side (true recurrence) causing recurrent sciatica. In these cases, when conservative treatment fails again, revision microdiscectomy is often performed. The number of patients who needed a lumbar re-operation for recurrent sciatica was higher in a long-term cohort study than in a randomized controlled trial (26 vs. 7–12%) [3, 4], showing again the difference between a cohort of patients from a real-world population versus a selection of patients from a RCT [5]. A systematic review comparing outcomes of fusion versus repeat discectomy for recurrent lumbar disc herniation showed that the results of revision microdiscectomy varied between 69 and 86% good or excellent outcome [6, 7], but the included studies were mostly small in sample size, had relatively short follow-up, and all but one came from outside of Europe. Furthermore, the long-term (10 years) results are largely unknown. The objectives of this study, therefore, were to investigate the long-term outcome, including functional scores, pain scores, and perceived recovery, in a large consecutive cohort of patients who had undergone a lumbar revision microdiscectomy more than 10 years earlier for recurrent sciatica caused by an MR-proven, re-herniated disc compressing the nerve root.

Methods

Study population

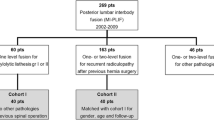

Between January 2007 and January 2010, 216 patients underwent a (first) revision microdiscectomy for a lumbar root nerve compression caused by an MR-proven lumbar disc re-herniation in OLVG, a large community hospital and spinal referral centre in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. Of these 216 patients, 29 had died by 2018. Excluded were 23 patients whose medical data or proper address or telephone number could not be retrieved, one patient who was terminally ill, and one who had migrated. In 2018, the remaining 162 patients were asked by telephone and/or by mail to participate in the study, and when they agreed, a questionnaire with informed consent letter was sent. Seven patients refused participation, and two patients who had difficulty understanding the Dutch language were excluded. Sixty-five patients did not respond despite a telephone reminder. The remaining 88 patients who provided informed consent were included for analysis (Fig. 1). The OLVG Institutional Medical Ethics Committee approved the study protocol.

Data collection

Age and gender were recorded from the responders and non-responders. The other baseline characteristics (body mass index (BMI), smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), and level of herniation) from the responders were recorded from the original medical records and referral letters, as were the follow-up period and whether there had been any further re-operations (in the same hospital), and this was cross-checked with the answers in the questionnaires.

The questionnaires included visual analogue scores (VAS) for leg and back pain (line from 0 to 100 mm) [8]; a Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ): a sciatica-specific disability scale that measures functional status in patients with pain in the leg or back (scores range from 0 to 23, with higher scores indicating worse functional status) [9]; an Oswestry Low Back Disability Questionnaire of which the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) can be derived (0–20% indicates minimal disability, 21–40%: moderate disability, 41–60%: severe disability, 61–80%: crippling back pain, and 81–100% means these patients are either bed-bound or have an exaggeration of their symptoms) [10]; a RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life [11]; and a seven-point Likert scale for a) general perceived recovery, b) leg pain, and c) back pain, ranging from complete recovery or no pain (1) to worse than ever (7). The questionnaires also included questions about any lumbar re-operation(s) (in the same hospital or elsewhere) and on the current use of pain medication for leg or back pain.

The collected data were coupled to a unique identification code and recorded in OpenClinica, a web-based software tool designed to capture clinical study data, in agreement with applicable regulations regarding privacy of study subjects.

Surgical technique of the revision microdiscectomy

All patients were re-operated through the same 2.5–5-cm midline incision via a unilateral or bilateral approach under general or epidural anaesthesia in a jackknife position by either one of four experienced neurosurgeons. All procedures were carried out using a headlight and loupe magnification (2.5–3x). A small partial re-laminotomy or broadening of medial facetectomy was performed as needed. The compressed nerve root was identified and carefully mobilized out of scar tissue, and the re-herniated disc or sequester was removed with rongeurs to free the nerve. Any loose fragments were removed from the disc space to prevent recurrent herniation, but no aggressive discectomy was attempted. Incidental perioperative durotomy was closed with 6/0 polypropylene sutures and/or with TachoSil®, or a subcutaneous-derived fat graft. The wound was closed in two layers, the skin with intra- or subcutaneous sutures.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test for normal distribution (values > 0.9 are considered as normally distributed). Normally distributed continuous variables are represented as a mean with a standard deviation. Continuous variables that are not normally distributed are represented as a median with an interquartile range (IQR; 25–75%). Normally distributed variables were tested with the Student’s t test, and data that were not normally distributed were tested with the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were tested with the Fisher’s exact test. All Likert scores were dichotomized into favourable (score 1 = complete and 2 = nearly complete recovery) and unfavourable outcome (score 3 = some recovery to score 7 = worse than ever). Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were exported from OpenClinica into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software (IBM SPSS 25; IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) for statistical analysis.

Results

Study population

The baseline characteristics of the responding patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age (SD) of the patients was 59.8 years (12.8), and the median [IQR] time of follow-up was 10 years [9.0–11.0]. The non-responding patients only differed significantly in mean age (SD) (51.8 (12.5)), not in gender.

Outcome scores

The median [IQR] VAS for leg pain for the whole group was 17.0/100 mm [3.0–52.0], for back pain was 31.0/100 mm [4.0–60.0], the mean (SD) total score of the RDQ was 9.0 (6.9), and for the Oswestry was 27.3 (22.3). The complete data, including the results for all domains of the RAND-36, are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

A favourable outcome in terms of general perceived recovery (scores 1 and 2 on the seven-point Likert scale for recovery, data available for n = 86 was reported by 35 patients (40%) (Table 2.).

A favourable outcome with respect to perceived leg pain (data available for n = 86) was present in 39 patients (45%) (Table 3). Thirty-five patients (41%) reported a favourable outcome concerning back pain (data available for n = 86) (Table 4).

The median [IQR] VAS for leg and back pain was significantly worse in the unfavourable outcome group (48.0/100 mm [16.0–71.0] vs. 3.0/100 mm [2.0–5.0] and 56.0/100 mm [27.0–74.0] vs. 4.0/100 mm [2.0–17.0], respectively; both p < 0.001) (Table 2.).

Thirty-one of the 88 patients (35%) were reported to have undergone a re-revision operation during the follow-up period, including 21 (24%) patients with a confirmed same level same side re-revision operation, six at another level, and in four patients, the level of re-operation was unknown. There was no significant difference in favourable or unfavourable recovery between patients who did or did not have a re-revision operation concerning general perceived recovery, leg pain, or back pain (Tables 5., 6., 7.).

Discussion

This study from a single, high-volume, spinal referral centre shows an unfavourable outcome in 60% of patients who underwent a revision microdiscectomy for recurrent lumbar disc herniation after long-term median follow-up of 10 years. The re-revision operation rate was 24%, with no difference in perceived outcome, leg pain, or back pain between the revision microdiscectomy and the re-revision microdiscectomy groups.

These disappointing results are in line with our previous study concerning the results of classic microdiscectomy for LSRS [4]. Again, the number of patients with an unfavourable outcome is at the high end of the range found in the literature for cohort studies or RCT’s [12,13,14], showing again the limited external validity of RCT’s, possibly caused by very strict patient selection and selective inclusion bias [4]. A cause for these disappointing results could be our strict criteria for dichotomization in favourable and unfavourable outcome, but from the patient’s perspective, it does not seem reasonable to consider the result 'same as before the operation' as other than an unfavourable outcome.

Another explanation could be that from 2007 onwards in the Netherlands, the strategy of prolonged conservative treatment of an LSRS may have resulted in a decrease in operations caused by a disc sequester and a relative increase in the number of operations caused by extruded fragments and massive posterior annulus defects or contained disc herniation, which are known for a higher chance of recurrence and revision operation and higher chance of unfavourable outcome [4, 15].

The most important reason for the high amount of patients with an unfavourable outcome is probably the long period of follow-up. There are not many studies in the literature that have a follow-up this long after revision microdiscectomy [6, 14, 16, 17]. In the Swedish study by Fritzell et al. [14], the number of patients with a satisfactory outcome after one year of follow-up was 58%. Disc degeneration is progressive over time and does not stop but is probably even accelerated by discectomy, so cumulative higher rates of re-herniation or recurrent back problems are to be expected with advancing age during a longer follow-up period [18, 19].

A limitation of this study is that we have no reliable data concerning the interval period. Thus, we have no information about the short- or intermediate-term effect of revision surgery.

In a previous study evaluating the five-year results of an RCT, 31% of patients after microdiscectomy fluctuated between episodes of good and poor outcome during the follow-up period [3].

So we have no information whether there was a large group of patients with no effect at all on revision surgery, just a short period of time or oscillating between good and bad recovery in between these 10 years.

The long follow-up period could also be a reason for the somewhat low response rate of 41%. As shown in our previous study, a low response rate does not necessarily equate to a lower study validity [4, 20], but still can be considered as a limitation. Although the mean age was lower in the group of non-responders, we have no indications suggesting that the outcome in the non-responders would be substantially different from the responding group.

Based on these findings, exploration of alternative treatment options may be justified, but the question is whether they lead to a better outcome in these patients. Discectomy with fusion has not been proven to be superior to revision discectomy alone [21]. Other alternative treatment options are medical management such as analgesics, muscle relaxants, anti-epileptics, antidepressants, or a combination, but most of the patients already had failed medical treatment prior to revision surgery. The effect of gabapentinoids on neuropathic pain seems borderline at best, and the adverse effects of long-term use of opioids are high with even possible higher mortality rates in patients using strong opioids. So pharmacological treatment options are helpful only in a minority of patients [22]. The effect of spinal epidural infiltration with corticosteroids as an alternative for revision surgery is at best only temporary, and the use of corticosteroids can have side effects or even lead to spinal cord infarction [23, 24]. Non-drug treatments such as rehabilitation can result in a higher percentage of patients returning to work compared to a control group, but there was no positive effect on pain intensity [25]. In some studies, spinal cord stimulation for recurrent radicular pain has been shown to generate a better outcome than re-operation [26, 27], but a recent placebo-controlled cross-over randomized clinical trial showed no difference in pain-related disability scores with the device on or off [28]. Furthermore, it has not yet been proven to be superior to conventional medical therapy and seems to be associated with higher costs and complications [29].

Conclusion

This single-centre, long-term cohort study shows an unfavourable outcome in a majority of patients who had a revision microdiscectomy for recurrent LSRS and a relatively high risk of re-revision microdiscectomy, with similar results. However, based on the equally disappointing results of the alternative treatment options, revision microdiscectomy for recurrent LSRS caused by a disc re-herniation may often still be a valid treatment option, despite 60% unfavourable outcome in the long-term, as short- and intermediate-term pain relief may also be a reasonable treatment goal. The results of our study may be useful to counsel patients in making appropriate treatment choices.

References

Arts M, Brand R, Van Den Akker E, Koes B, Bartels R, Tan WF, Peul W (2010) Tubular discectomy versus conventional microdiscectomy for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation: two year results of a double-blinded randomised controlled trial. In: spine conference publication: (var.pagings)

Jensen RK, Kongsted A, Kjaer P, Koes B (2019) Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ 367:l6273. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6273

Lequin MB, Verbaan D, Jacobs WC, Brand R, Bouma GJ, Vandertop WP, Peul WC, Leiden-The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study G, Wilco CP, Bart WK, Ralph TWMT, BvdH W, Ronald B (2013) Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica 5-year results of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002534

Lequin MB, Verbaan D, Schuurman PR, Tasche S, Peul WC, Vandertop WP, Bouma GJ (2022) Microdiscectomy for sciatica: reality check study of long-term surgical treatment effects of a Lumbosacral radicular syndrome (LSRS). Eur Spine J 31:400–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-07074-x

Rothwell PM (2005) External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?” The Lancet 365:82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8

Suk KS, Lee HM, Moon SH, Kim NH (2001) Recurrent lumbar disc herniation: results of operative management. Spine 26:672–676

Drazin D, Ugiliweneza B, Al-Khouja L, Yang D, Johnson P, Kim T, Boakye M (2016) Treatment of recurrent disc herniation: a systematic review. Cureus 8:e622. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.622

Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (1997) The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain 72:95–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00005-5

Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB (1995) Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20:1899–1908. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB (2000) The oswestry disability index. Spine 25:2940–2952. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L (1992) Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 305:160–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160

Fu T-S, Lai P-L, Tsai T-T, Niu C-C, Chen L-H, Chen W-J (2005) Long-term results of disc excision for recurrent lumbar disc herniation with or without posterolateral fusion. Spine 30:2830–2834

Abdu RW, Abdu WA, Pearson AM, Zhao W, Lurie JD, Weinstein JN (2017) Reoperation for recurrent intervertebral disc herniation in the spine patient outcomes research trial analysis of rate, risk factors, and outcome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 42:1106–1114. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000002088

Fritzell P, Knutsson B, Sanden B, Strömqvist B, Hägg O (2015) Recurrent versus primary lumbar disc herniation surgery: patient-reported outcomes in the swedish spine register swespine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 473:1978–1984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3596-8

Carragee EJ, Han MY, Suen PW, Kim D (2003) Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol 85:102–108

Ahsan K, Najmus S, Hossain A, Khan SI, Awwal MA (2012) Discectomy for primary and recurrent prolapse of lumbar intervertebral discs. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 20:7–10

Patel N, Pople IK, Cummins BH (1995) Revisional lumbar microdiscectomy: an analysis of operative findings and clinical outcome. Br J Neurosurg 9:733–738

Schrimpf D, Haag M, Pilz LR (2014) Possible combinations of electronic data capture and randomization systems. principles and the realization with RANDI2 and openclinica. Methods Inf Med 53:202–207. https://doi.org/10.3414/ME13-01-0074

Schroeder JE, Dettori JR, Brodt ED, Kaplan L (2012) Disc degeneration after disc herniation: are we accelerating the process? Evid Based Spine Care J 3:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1328141

Morton SMB, Bandara DK, Robinson EM, Carr PEA (2012) In the 21st century, what is an acceptable response rate? Aust N Z J Public Health 36:106–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00854.x

Kerezoudis P, Goncalves S, Cesare JD, Alvi MA, Kurian DP, Sebastian AS, Nassr A, Bydon M (2018) Comparing outcomes of fusion versus repeat discectomy for recurrent lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 171:70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.05.023

Ganty P, Sharma M (2012) Failed back surgery syndrome: a suggested algorithm of care. Br J Pain 6:153–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463712470222

Ter Meulen BC, van Dongen JM, Maas E, van de Vegt MH, Haumann J, Weinstein HC, Ostelo R (2023) Effect of transforaminal epidural corticosteroid injections in acute sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 39:654–662. https://doi.org/10.1097/ajp.0000000000001155

Glaser SE, Shah RV (2010) Root cause analysis of paraplegia following transforaminal epidural steroid injections: the “unsafe” triangle. Pain Physician 13:237–244

Durand G, Girodon J, Debiais F (2015) Medical management of failed back surgery syndrome in Europe: evaluation modalities and treatment proposals. Neurochirurgie 61:S57–S65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2015.01.001

North RB, Kidd DH, Farrokhi F, Piantadosi SA (2005) Spinal cord stimulation versus repeated lumbosacral spine surgery for chronic pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurosurgery 56:98–107

North RB, Kumar K, Wallace MS, Henderson JM, Shipley J, Hernandez J, Mekel-Bobrov N, Jaax KN (2011) Spinal cord stimulation versus re-operation in patients with failed back surgery syndrome: an international multicenter randomized controlled trial (evidence study). Neuromodulation 14:330–336

Hara S, Andresen H, Solheim O, Carlsen SM, Sundstrøm T, Lønne G, Lønne VV, Taraldsen K, Tronvik EA, Øie LR, Gulati AM, Sagberg LM, Jakola AS, Solberg TK, Nygaard ØP, Salvesen ØO, Gulati S (2022) Effect of spinal cord burst stimulation vs. placebo stimulation on disability in patients with chronic radicular pain after lumbar spine surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 328:1506–1514. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.18231

Dhruva SS, Murillo J, Ameli O, Morin PE, Spencer DL, Redberg RF, Cohen K (2023) Long-term outcomes in use of opioids, nonpharmacologic pain interventions, and total costs of spinal cord stimulators compared with conventional medical therapy for chronic pain. JAMA Neurol 80:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.4166

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lequin, M.B., Verbaan, D., Schuurman, P.R. et al. The long-term outcome of revision microdiscectomy for recurrent sciatica. Eur Spine J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-024-08199-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-024-08199-5