Abstract

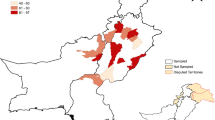

Coronaviride is a colossal family of viruses that cause a variety of diseases in humans and other animals. As of late, a novel coronavirus, not anterior-optically discerned in humans, has been identified in a denizen of the Middle East. There is growing evidence that the Camelus dromedarius is host species for the virus and plays an important role of a source of human infection. Along these lines, the authors decided to detect coronaviruses in dromedary camels in two high-risk areas of Iran by employing an reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay. In the present study, nasal swab specimens were collected from 98 camels (C. dromedarius) traditionally reared in southeast and northwest of Iran. The detection of pancoronavirus was carried out, using RT-PCR. Pancoronavirus RNA was observed in seven cases among 98 nasal swab samples. Among these, 4 positive samples belonged to Azerbaijan province located in northwest of Iran and 3 positive samples were taken from southeast of Iran. The results of this study contribute to raising the hypothesis to the extent of transmission and risk factors for human infection and public health in Iran.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronaviride is an astronomically immense family of viruses that induce a diversity of diseases in humans, from a prevalent cold to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Additionally, these viruses cause disease in a wide assortment of animal species (Drosten et al. 2003; Kuiken et al. 2003; Perlman and Netland 2009; Vabret et al. 2006; Vabret et al. 2008; WHO 2013). In late 2012, a novel coronavirus, not already found in humans, was distinguished in an inhabitant of the Middle East (Corman et al. 2011; Zaki et al. 2012). Thus far, the coronavirus has been kenned as the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Bermingham et al. 2012; Buchholz 2013; Van Boheemen et al. 2012; Zaki et al. 2012). As per the World Health Organization (WHO), worldwide cases meaning the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) were 1599 cases affirmed by research facilities until October 2015. These cases included at least 574 deaths (case fatality rate of 36%) since the first cases were reported in September 2012 (WHO 2015).

There is confirmation that the dromedary camels are host species for the infection and they assume a part as a wellspring of human disease (WHO 2013). An investigation in Egypt, utilizing reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), detected MERS-CoV in 3.6% (4 out of 110) of ostensibly salubrious dromedary camels in an abattoir. The genetic sequence of the viruses demonstrates the lowest contrasts from a reference strain previously taken from a human case (Chu et al. 2014).

Viral culture is a standard test for diagnosis of respiratory infections (van Elden et al. 2002). However, as it is difficult to grow coronaviruses in cell culture (Siddell et al. 1983), RT-PCR has been produced to acquire more affectable and fast indicative results. This pancoronavirus assay is a utilizable implement for screening sample amassments for the presence of all kenned coronaviruses (Moës 2005; Zaki et al. 2012). As Iran recently reported its sixth human MERS-CoV case and the fifth death from the disease, it is vital to evaluate the situation of the infection in camels as a source of the virus. Therefore, the authors decided to detect coronaviruses in dromedary camels in two high-risk areas of Iran by applying an RT-PCR assay.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

After a 4-month period (from January to May 2014), the nasal swab samples were gathered aseptically with sterile absorbent swabs soaked in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) from 98 apparently healthy camels (C. dromedarius) which were reared traditionally in Kerman and West Azerbaijan provinces, Iran.

Sample processing

At first, the swab tips were squeezed, and vortexes and 140 μl of the solution obtained were taken for RNA extraction. Subsequently, 60 μl of RNA concentrate, which was received for the most part as portrayed by the producer’s aide (Qiagen, Germany), was stored at −20 °C.

PCR process

The coronavirus RNA was recognized by amplifying a 251-bp section of the coronavirus polymerase gene utilizing the accompanying preliminary set: Cor-FW (5′-TGGGGAGTAATGAACCCGGTA-3′) and Cor-RV (5′-ACATGTAAAAGAGCTAATAACAC-3′) (Copenhagen, Denmark). PCR amplifications were performed in 25-μl reaction volumes containing 5 μl of the extract and 20 μl of the master mix (containing 10 μl buffer, 2 μl dNTP mix, 1.8 μl enzyme Mix (a combination of reverse transcriptase and Hot Star Taq DNA polymerase), 4 μM of forward and reverse primer, and RNase-free water). The reverse transcriptase reaction was launched during 30 min at 50 °C; it underwent PCR initiation at 95 °C for 15 min, 50 cycles of amplification (30-s denaturation at 94 °C and 1-min extension at 72 °C), and finally the last augmentation by hatching at 72 °C for 10 min. Then, 5 μl of the product mixed with 1 μl of the loading buffer was loaded on agarose gel (1.2%) and run at 90 V for 30 min. The coronavirus-positive samples will be subject to a sequence.

Results

Pancoronavirus RNA was identified in seven cases among 98 nasal swab samples. Four positive samples belonged to West Azerbaijan province, northwest of Iran, and the remaining three were taken from Kerman province, southeast of Iran (Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

The late dangerous human contaminations made by the MERS-CoV realized an astonishing interest in the revelation of coronaviruses in individuals and farm animals. The first studies were carried out to investigate whether or not a camel is a possible source and reservoir of the virus (Haagmans et al. 2014a; Memish et al. 2014).

The positive serological results from 50 serum tests taken from dromedary camels in Oman exhibited a high titer of neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV (Reusken et al. 2013b). Camels infected with MERS-CoV may not show any clinical signs (Assiri et al. 2013; Azhar et al. 2014; WHO 2014a, b).

Thus, it is not possible to know whether or not an animal in a farm, market, race track, or slaughterhouse is excreting the virus and is able to infect humans through their nasal discharges and feces and potentially in their milk and urine (Adney et al. 2014). The virus may also be found in the organs and meat of the infected animals (WHO 2014). C. dromedarius is increasingly apperceived as an indigenous reservoir for human coronaviruses. A pancoronavirus RT-PCR examination is an apt strategy to distinguish the majority of the coronaviruses in clinical specimens. Other than speedy screening for a few pathogens in one test, it supplies the likelihood to distinguish aforetime obscure coronaviruses.

In recent studies, scientists have tested the sera of sheep, dairy cattle, goats, and camels from the Middle East and some different districts for the nearness of antibodies against the MERS-CoV. Interestingly, the results showed that all samples taken from the camels were positive against MERS-CoV (Hemida et al. 2013; Meyer et al. 2014; Perera et al. 2013; Reusken et al. 2013a). However, no anti-MERS-CoV antibodies were found in any of the other tested animals (Reusken et al. 2013b).

The results of previous studies also indicate that humans who had had interaction with camels developed a higher seroprevalence than those without contact (Reusken et al. 2013a; Reusken et al. 2013b). Be that as it may, camels do not essentially need to build up the sickness; however, they are liable to transmit the pathogen (Müller et al. 2015). A recent study has demonstrated that indistinguishable MERS-CoV RNA sections were identified in an air test gathered from the dwelling place of the camel where there was a common comparable MERS-CoV with a contaminated individual (Azhar et al. 2014).

On 11 June 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that Kuwait found the virus in five camels. They also confirmed the first two MERS-CoV cases in Iran (WHO 2014b). According to the WHO recent report, all the patients who died from MERS-CoV were inhabitants of Kerman province, Iran (WHO 2014a; Yousefi et al. 2016). Therefore, our research group designed a study to focus on the detection of coronaviruses in camels in Kerman province, Iran.

However, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran has reported that the above-mentioned patients had no contact with animals or did not consume raw camel products before their illness; however, they had close contact with Umrah pilgrims who had an influenza-like illness. Previous studies affirm a remarkable similarity between MERS-CoVs conveyed by humans and camels (Abdulaziz et al. 2014; Haagmans et al. 2014b) and bolster the theory that human MERS-CoV contamination might be procured straightforwardly from camels.

The first reported case of coronavirus infection in C. dromedarius in Iran raises the possibility that a significant proportion of cases might be infected or will be infected in the future, thus improving the hypothesis to the extent of transmission and risk factors for humans.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the implementation of a perpetual veterinary surveillance program for detecting coronaviruses in dromedary camels may avail our control of the transit method of coronavirus infections.

References

Abdulaziz N. Alagaili TB, Nischay Mishra, Vishal Kapoor, Stephen C. Sameroff, Emmie de Wit, Vincent J. Munster, Lisa E. Hensley IS Zalmout, Amit Kapoor, Jonathan H. Epstein, William B. Karesh, Peter Daszak, Osama B. Mohammed, W. Ian Lipkin (2014) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia mbioasmorg 5 doi:10.1128/mBio.00884–14

Adney DR et al. (2014) Replication and shedding of MERS-CoV in upper respiratory tract of inoculated dromedary camels Emerg Infect Dis 20:1999–2005

Assiri A et al (2013) Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 13:752–761

Azhar EI, El-Kafrawy SA, Farraj SA, Hassan AM, Al-Saeed MS, Hashem AM, Madani TA (2014) Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. New England Journal of Medicine 370:2499–2505. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401505

Bermingham A et al. (2012) Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012 Euro Surveill 17

Chu DKW et al (2014) MERS coronaviruses in dromedary camels, Egypt. Emerging Infectious Diseases 20:1049–1053. doi:10.3201/eid2006.140299

Corman V et al (2011) Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro surveillance: bulletin europeen sur les maladies transmissibles=European communicable disease bulletin 17:395–405

Drosten C et al (2003) Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 348:1967–1976

Haagmans BL et al (2014a) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis 14:140–145

Haagmans BL et al (2014b) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis 14:140–145. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(13)70690-x

Hemida M et al. (2013) Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013 Eurosurveillance

Kuiken T et al (2003) Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 362:263

Memish ZA et al (2014) Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1012–1015

Meyer B, Drosten C, Müller MA (2014) Serological assays for emerging coronaviruses: challenges and pitfalls. Virus research 194:175–183

Moës EV, Keyaerts L, Zlateva E, Li K, Maes S, Pyrc P, Berkhout K, van der Hoek B, Van Ranst Marc L (2005) A novel pancoronavirus RT-PCR assay: frequent detection of human coronavirus NL63 in children hospitalized with respiratory tract infections in Belgium. BMC Infect Dis 5(6)

Müller MA et al (2015) Presence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide, cross-sectional, serological study. Lancet Infect Dis 15:559–564. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(15)70090-3

Perera R et al (2013) Seroepidemiology for MERS coronavirus using microneutralisation and pseudoparticle virus neutralisation assays reveal a high prevalence of antibody in dromedary camels in Egypt, June 2013. Euro Surveill 18:20574

Perlman S, Netland J (2009) Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:439–450

Reusken CB et al (2013a) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis 13:859–866

Reusken CBEM et al (2013b) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis 13:859–866. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(13)70164-6

Siddell S, Wege H, Ter Meulen V (1983) The biology of coronaviruses. Journal of General Virology 64:761–776

U Buchholz, MA Muller, A Nitsche, A Sanewski, N Wevering, T Bauer-Balci, F Boni, C Drosten, B Schweiger, T Wolff, D Muth, B Meyer, S Buda, G Krause, L Schaade, W Haas (2013) Contact investigation of a case of human novel coronavirus infection treated in a German hospital, October-November 2012. Surveillance and outbreak reports

Vabret A, Dina J, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Corbet S, Freymuth F (2006) Detection of the new human coronavirus HKU1: a report of 6 cases. Clin Infect Dis 42:634–639

Vabret A, Dina J, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Tripey V, Brouard J, Freymuth F (2008) Human (non-severe acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus infections in hospitalised children in France. J Paediatr Child Health 44:176–181

Van Boheemen S et al. 2012.Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio. 2012; 3: e00473–12. In: PubMed Abstract| Publisher Full Text| PubMed Central Full Text OpenURL

van Elden LJ, van Kraaij MG, Nijhuis M, Hendriksen KA, Dekker AW, Rozenberg-Arska M, AM v L (2002) Polymerase chain reaction is more sensitive than viral culture and antigen testing for the detection of respiratory viruses in adults with hematological cancer and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 34:177–183

WHO (13 June 2014a) Update on MERS-CoV transmission from animals to humans, and interim recommendations for at-risk groups http://www.whoint/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/en/

WHO (2014b) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—update.27 March Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2014_03_27_mers/en/

WHO (2013) WHO guidelines for investigation of cases of human infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) http://www.whoint/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/MERS_CoV_investigation_guideline_Jul13pdf

WHO (2015) Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) situation update 22 October 2015 www.healthgovau/mers-coronavirus

Yousefi M, Dehesh MM, Farokhnia M (2016) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Iran in 2014 Japanese journal of infectious diseases

Zaki AM, Van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, RA F (2012) Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367:1814–1820

Acknowledgement

This research was financially supported by the research council of the Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Iran (grant number 942). The authors would like to express their deep sense of gratitude and sincere thanks to Dr. Hadi Hasibi, Dr. Amin Paydar Ardakani, and Dr. Fattah Iranmanesh for their assistance in sample taking.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All ethical considerations utilizing animals were considered conscientiously, and the experimental protocol was affirmed by the Ethics Committee of KUMS, Kerman, Iran.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khalili Bagaloy, H., Sakhaee, E. & Khalili, M. Detection of pancoronavirus using PCR in Camelus dromedarius in Iran (first report). Comp Clin Pathol 26, 193–196 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-016-2368-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-016-2368-0