Abstract

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a congenital malformation in which the pancreatic and bile ducts join anatomically outside the duodenal wall. Japanese clinical practice guidelines on how to deal with PBM were made in 2012, representing a world first. According to the 2013 revision to the diagnostic criteria for PBM, in addition to direct cholangiography, diagnosis can be made by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), 3-dimensional drip infusion cholangiography computed tomography, endoscopic ultrasonography (US), or multiplanar reconstruction images by multidetector row computed tomography. In PBM, the common channel is so long that sphincter action does not affect the pancreaticobiliary junction, and pancreatic juice frequently refluxes into the biliary tract. Persistence of refluxed pancreatic juice injures epithelium of the biliary tract and promotes cancer development, resulting in higher rates of carcinogenesis in the biliary tract. In a nationwide survey, biliary cancer was detected in 21.6 % of adult patients with congenital biliary dilatation (bile duct cancer, 32.1 % vs. gallbladder cancer, 62.3 %) and in 42.4 % of PBM patients without biliary dilatation (bile duct cancer, 7.3 % vs. gallbladder cancer, 88.1 %). Pathophysiological conditions due to pancreatobiliary reflux occur in patients with high confluence of pancreaticobiliary ducts, a common channel ≥6 mm long, and occlusion of communication during contraction of the sphincter. Once the diagnosis of PBM is established, immediate prophylactic surgery is recommended. However, the surgical strategy for PBM without biliary dilatation remains controversial. To detect PBM without biliary dilatation early, MRCP is recommended for patients showing gallbladder wall thickening on screening US under suspicion of PBM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

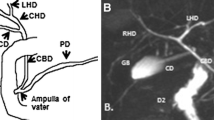

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a congenital malformation in which the pancreatic and bile ducts join anatomically outside the duodenal wall. The sphincter of Oddi is normally located at the distal end of the pancreatic and bile ducts and regulates the outflow of bile and pancreatic juice. In PBM, the common channel is so long that action of the sphincter of Oddi does not directly affect the pancreaticobiliary junction. As a result, reciprocal reflux of pancreatic juices and bile occurs. As the fluid pressure in the pancreatic duct usually exceeds that in the bile duct, reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tract frequently occurs in PBM. Persistence of refluxed pancreatic juice injures the epithelium of the biliary tract and promotes cancer development, resulting in higher rates of carcinogenesis in the biliary tract of PBM (Fig. 1). PBM can be divided into PBM with biliary dilatation (congenital biliary dilatation) and PBM without biliary dilatation [1, 2].

The pathophysiology of pancreaticobiliary maljunction [3]

Japanese clinical practice guidelines on how to deal with PBM were created in 2012, as the first in the world [3]. Diagnostic criteria for PBM were revised in 2013, taking recent advances in diagnostic imaging techniques into consideration [4]. Based on the guidelines and new diagnostic criteria, we describe herein recent topics and problems in the management of PBM, with a focus on biliary cancer.

Diagnostic criteria for PBM 2013

Diagnostic criteria of PBM were proposed in 1987 [5], and were slightly revised in 1990 and published in English in 1994 [6]. In 2013, these criteria underwent thorough revision, 23 years to the day since the previous version (Table 1) [4]. Although no significant changes have been made to the definition of PBM, diagnostic modalities have undergone substantial advances in recent years. As no radiological modalities were initially available that could show the status of the pancreaticobiliary junction outside the duodenal wall, PBM was diagnosed when a lack of effect of the sphincter of Oddi on the pancreaticobiliary junction was verified on direct cholangiography such as with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has now become popular as a noninvasive method for obtaining high-quality images of the pancreaticobiliary tree, and it is replacing diagnostic ERCP for many pancreatobiliary diseases. Many PBM cases can be diagnosed from MRCP based on findings of an anomalous union between the common bile duct and pancreatic duct in addition to a long common channel [7–10]. MRCP is thus useful for diagnosing children and screening for PBM [7]. However, accurate diagnosis of PBM is difficult in cases with a relatively short common channel (Fig. 2a, b) [11]. In cases with a common channel ≤9 mm on MRCP, direct cholangiography is needed to confirm PBM [12]. PBM can be diagnosed if junction outside the wall can be depicted by high-resolution images with multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) provided by multidetector row computed tomography (MD-CT), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) [3, 13, 14].

Amylase levels in bile are markedly elevated (>10,000 IU/l) in most cases of PBM, but are not elevated at all in some cases [15, 16]. Furthermore, elevation of pancreatic enzyme levels in bile and hyperplastic changes to the gallbladder mucosa are sometimes observed in some cases with a relatively long common channel in which the effect of the sphincter reaches the pancreaticobiliary junction (high confluence of pancreaticobiliary ducts) [17–19].

Since the maximum diameter of the common bile duct correlates positively with age, standard values for the maximum diameter of the common bile duct in each age group appear appropriate for accurate evaluation of the presence of bile duct dilatation [20–22].

Biliary cancer associated with PBM

Incidence and characteristics

Biliary cancers are frequently observed in adult patients with PBM [23–25]. According to a nationwide survey in Japan (n = 2561) [2], biliary cancer was detected in 21.6 % of adult patients with congenital biliary dilatation and in 42.4 % of PBM patients without biliary dilatation. In patients with biliary cancers in association with PBM, the location ratio of cancers in the bile duct and gallbladder were 32.1 % and 62.3 % in congenital biliary dilatation, and 7.3 % and 88.1 % in PBM patients without biliary dilatation, respectively. The mean age at which PBM patients developed biliary cancer was 60.1 years for gallbladder cancer and 52.0 years for bile duct cancer among patients with congenital biliary dilatation, and 58.6 years for gallbladder cancer in PBM patients without biliary dilatation. Such patients develop biliary cancers 15–20 years earlier than patients without PBM [26].

In PBM patients, biliary cancers frequently develop as simultaneous and/or metachronous double cancers. Of 37 patients with simultaneous double or multiple biliary cancers, 19 patients (51 %) suffered from concurrent PBM [3, 27–31].

The ratio of gallstone detection in PBM patients who developed gallbladder cancer was lower than that in the biliary cancer population without PBM [2, 3, 32]. In our series, the ratios were 10 % and 62 %, respectively [1].

Mechanism of biliary carcinogenesis

The mechanisms of carcinogenesis in PBM appear to be related to the persistence of refluxed pancreatic juice into the biliary tract. Refluxed proteolytic pancreatic enzymes and phospholipase A2 are activated in the biliary tract and strongly cytotoxic substances such as lysolecithin are produced. The resulting chronic inflammation provokes repeated cycles of damage and healing in the biliary mucosal epithelia. These alterations in the mucosal epithelia, in conjunction with DNA mutations, finally promote cancer development and progression (Fig. 3) [1, 3, 33, 34]. The sequence of hyperplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma, regarded as the prevailing mechanism underlying the development of biliary tract cancer in PBM, is thought to differ from both the adenoma-carcinoma sequence and de novo carcinogenesis associated with biliary tract cancer in the population without PBM [35–37].

Mechanism of biliary carcinogenesis in pancreaticobiliary maljunction [1]

In our series, the gallbladder mucosa was significantly higher in PBM than in controls. The incidence of epithelial hyperplasia of the gallbladder and the Ki-67 labeling index of the gallbladder epithelium were significantly higher in PBM than in controls. K-ras mutations in the noncancerous epithelium of the gallbladder were detected in 36 % of PBM patients [1, 19]. Considering that increased cell proliferation is linked to the development of cancer by means of tumor promotion and an increased rate of random mutations, the gallbladder mucosa of PBM patients can be considered to represent a premalignant region.

Treatment of PBM

Once a diagnosis of PBM has been established, immediate prophylactic surgery is recommended before the onset of malignant changes. Cholecystectomy and resection of the extrahepatic bile duct (flow-diversion surgery) is an established standard for the surgical treatment of congenital biliary dilatation [3, 22]. Internal drainage operations have been abandoned because of the high risk of postoperative carcinogenesis.

On the other hand, treatment of PBM without biliary dilatation and without cancer is controversial. Prophylactic cholecystectomy is performed in many institutes, as most biliary cancers that develop in PBM patients without biliary dilatation are gallbladder cancers [38, 39]. However, some surgeons propose excision of the extrahepatic bile duct together with the gallbladder for PBM patients without biliary dilatation [23], because the frequency of bile duct cancer in PBM patients without biliary dilatation is higher compared to that in the general population [2], and K-ras and/or p53 gene mutations are also reportedly seen in the bile duct of PBM patients without biliary dilatation [23, 40].

Strategy for early diagnosis of PBM

Compared to congenital biliary dilatation, PBM cases without biliary dilatation rarely evoke symptoms, and most patients are not diagnosed until the onset of advanced stage gallbladder cancer [1, 38]. Detecting PBM before the development of biliary cancer is important in order to allow for prophylactic surgery. Epithelial hyperplasia of the gallbladder induced by longstanding continuous stasis of the bile intermingled with refluxed pancreatic juice is a characteristic pathological change in PBM patients [41–43]. To achieve early detection of PBM without biliary dilatation, MRCP is warranted in patients showing thickening of the gallbladder wall on screening US under suspicion of PBM (Fig. 2c) [44].

High confluence of pancreaticobiliary ducts

The frequency of common channel formation ranges from 55 % to 91 % [17], and the mean length of the common channel has been reported as 4.5 mm [45]. To investigate the clinical significance of a relatively long common channel, we defined high confluence of pancreaticobiliary ducts (HCPBD) as a disease state in which the common channel length is ≥6 mm and communication is occluded when the sphincter of Oddi is contracted (Fig. 4a, b) [17].

Images from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography of high confluence of pancreaticobiliary ducts (HCPBD) [3]. The bile and pancreatic ducts form a common channel (arrows) 8 mm long during sphincter relaxation (a). Communication between these two ducts is interrupted during contraction of the sphincter of Oddi (b)

In our series of 95 HCPBD patients, reflux of contrast medium into the pancreatic duct was detected in 86 % of patients who underwent postoperative T-tube cholangiography. Elevated amylase levels in bile were observed in all patients, although the mean levels were significantly lower than those in PBM patients. Gallbladder cancer was identified in 11 HCPBD patients (12 %). Similar to PBM patients, hyperplastic changes with increases in both the proliferative activity of epithelial cells and K-ras mutations were also detected in the noncancerous epithelium of the gallbladder in HCPBD patients [1, 18, 19]. A relatively long common channel also appears to represent an important risk factor for the development of gallbladder cancer. However, several differences exist between HCPBD and PBM without biliary dilatation in terms of other features, such as gender predilections, age at diagnosis, incidence of concomitant gallbladder cancer, and biliary amylase levels. HCPBD appears to represent an intermediate clinical condition that is both morphologically and functionally difficult to differentiate clearly from PBM. We consider that HCPBD should currently be managed as a disease entity independent of PBM in terms of the appropriate therapeutic strategies [1, 22].

Conclusions

Biliary cancers occur frequently through proliferative processes provoked by chronic inflammation resulting from the persistence of pancreatic juice refluxed through a long common channel. Once PBM is diagnosed, immediate prophylactic surgery is recommended before malignant changes develop. It is important to diagnose PBM before the onset of biliary carcinogenesis. To achieve early detection of PBM without biliary dilatation, MRCP is recommended for patients showing gallbladder wall thickening on screening US under suspicion of PBM. Further investigations and surveillance studies are also needed to clarify appropriate surgical strategies for PBM without biliary dilatation.

References

Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Anjiki H, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:S84–8.

Morine Y, Shiamda M, Takamatsu H, et al. Clinical features of pancreaticobiliary maljunction: update analysis of 2nd Japan-nationwide survey. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2013;20:472–80.

Kamisawa T, Ando H, Suyama M, et al. Japanese clinical practice guidelines for pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:731–59.

Kamisawa T, Ando H, Hamada Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria for pancreaticobiliary maljunction 2013. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:159–61.

The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSGPM), Committee for Diagnostic Criteria for Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction (in Japanese). Tan to Sui. 1987;8:115–8.

The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSPBM), The Committee of JSPBM for Diagnostic Criteria. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J HeptobiliaryPancreat Surg. 1994;1:219–21.

Hirohashi S, Hirohashi R, Uchida H, et al. Pancreatitis: evaluation with MR cholangiopancreatography in children. Radiology. 1997;203:411–5.

Sugiyama M, Baba M, Atomi Y, et al. Diagnosis of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction: value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Surgery. 1998;123:391–7.

Matos C, Nicaise N, Deviere J, et al. Choledochal cysts: comparison of findings at MR cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in eight patients. Radiology. 1998;209:443–8.

Kim MJ, Han SJ, Yoon CS, et al. Using MR cholangiopancreatography to reveal anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union in infants and children with choledochal cysts. Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:209–14.

Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, et al. MRCP of congenital pancreaticobiliary malformation. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:129–33.

Itokawa F, Kamisawa T, Nakano T, et al. Exploring the length of the common channel of pancreaticobiliary maljunction on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. J HepatobiliaryPancreat Sci. doi:10.1002/jhbp.168 (Epub ahead of print)

Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography for diagnosing anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:261–7.

Yusuf TE, Bhutani MS. Role of endoscopic ultrasonography in diseases of the extrahepatic biliary system. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:243–50.

Matsuda M, Watanabe G, Hashimoto M, et al. Evaluation of pancreaticobiliary maljunction and low bile amylase levels (in Japanese with English abstract). J Jpn Biliary Assoc. 2007;21:119–24.

Todani T, Urushihara N, Morotomi Y, et al. Characteristics of choledochal cysts in neonates and early infants. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1995;5:143–5.

Kamisawa T, Amemiya K, Tu Y, et al. Clinical significance of a long common channel. Pancreatology. 2002;2:122–8.

Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y, et al. Pathologic changes in the non-carcinomatous epithelium of the gallbladder in patients with a relatively long common channel. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:56–60.

Kamisawa T, Go K, Chen PY, et al. Lesions with a high risk of carcinogenesis in the gallbladder of patients with a long common channel. Dig Endosc. 2006;18:192–5.

Hamada Y, Takehara H, Ando H, et al. Definition of biliary dilatation based on standard diameter of the bile duct in children (in Japanese). Tan to Sui. 2010;31:1269–72.

Itoi T, Kamisawa T, Fujii H, et al. Extrahepatic bile duct measurement by using transabdominal ultrasound in Japanese adults: multi-center prospective study. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1045–50.

Kamisawa T, Ando H, Shimada M, et al. Recent advances and problems in the management of pancreaticobiliary maljunction: feedback from the guidelines committee. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:87–92.

Funabiki T, Matsubara T, Miyakawa S, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:159–69.

Deng YL, Cheng NS, Lin YX, et al. Relationship between pancreaticobiliary maljunction and gallbladder carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:570–80.

Li Y, Wei J, Zhao Z, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction is associated with common bile duct carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Sci World J. 2013;618670. doi:10.1155/2013/618670

Matsuda T, Marugame T, Kamo K, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2003: based on data from 13 population-based cancer registries in the monitoring of cancer incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:850–8.

Ogawa A, Sugo H, Takamori S, et al. Double cancers in the common bile duct: molecular genetic findings with an analysis of LOH. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:374–8.

Okamoto A, Tsuruta K, Matsumoto G, et al. Papillary carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: characteristic features and implications in surgical treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:394–401.

Hori H, Ajiki T, Fujita T, et al. Double cancer of gall bladder and bile duct not associated with anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary duct system. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:638–42.

Itoh T, Fuji N, Taniguchi H, et al. Double cancer of the cystic duct and gallbladder associated with low junction of the cystic duct. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:338–43.

Fujii T, Kaneko T, Sugimoto H, et al. Metachronous double cancer of the gallbladder and common bile duct. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:280–5.

Miyazaki M, Takada T, Miyakawa S, et al. Risk factors for biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas and prophylactic surgery for these factors. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:15–24.

Shimada K, Yanagisawa J, Nakayama F. Increased lysophosphatidylcholine and pancreatic enzyme content in bile of patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction. Hepatology. 1991;13:438–44.

Tsuchida A, Itoi T. Carcinogenesis and chemoprevention of biliary tract cancer in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:130–5.

Kozuka S, Tsubone N, Yasui A, et al. Relation of adenoma to carcinoma in the gallbladder. Cancer. 1982;50:2226–34.

Watanabe H, Date K, Itoi T, et al. Histological and genetic changes in malignant transformation of gallbladder adenoma. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:136–9.

Aoki T, Tsuchida A, Kasuya K, et al. Carcinogenesis in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. In: Koyanagi Y, Aoki T, editors. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Tokyo: Igaku Tosho; 2002. p. 295–302.

Tashiro S, Imaizumi T, Ohkawa H, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:345–51.

Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction without congenital choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1998;85:911–6.

Matsubara T, Sakurai Y, Zhi L, et al. K-ras and p53 gene mutations in noncancerous biliary lesions of patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:312–21.

Tsuchida A, Itoi T, Endo M, et al. Pathological features and surgical outcome of pancreaticobiliary maljunction without dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct. Oncol Rep. 2004;11:269–76.

Tanno S, Obara T, Fujii T, et al. Proliferative potential and K-ras mutation in epithelial hyperplasia of the gallbladder in patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. Cancer. 1998;83:267–75.

Yamamoto M, Nakajo S, Tahara E, et al. Mucosal changes of the gallbladder in anomalous union with the pancreatico-biliary duct system. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187:241–6.

Takuma K, Kamisawa T, Tabata T, et al. Importance of early diagnosis of pancreaticobiliary maljunction without biliary dilatation. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3409–14.

Dowdy GS, Waldron GW, Brown WG. Surgical anatomy of the pancreatobiliary ductal system. Arch Surg. 1962;84:229–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kamisawa, T., Kuruma, S., Tabata, T. et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and biliary cancer. J Gastroenterol 50, 273–279 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-1015-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-1015-2