Abstract

We reviewed articles on the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in Japan to clarify these features of GERD in this country. Although the definition of GERD depends on the individual study, the prevalence of GERD has been increasing since the end of the 1990s. The reasons for the increase in the prevalence of GERD may be due to increases in gastric acid secretion, a decrease in the Helicobacter pylori infection rate, more attention being paid to GERD, and advances in the concept of GERD. More than half of GERD patients had non-erosive reflux disease, and the majority (87%) of erosive esophagitis was mild type, such as Los Angeles classification grade A and grade B. There were several identified risk factors, such as older age, obesity, and hiatal hernia. In particular, mild gastric atrophy and absence of H. pylori infection influence the characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. We also discuss GERD in the elderly; asymptomatic GERD; the natural history of GERD; and associations between GERD and peptic ulcer disease and H. pylori eradication. We examined the prevalence of GERD in patients with specific diseases, and found a higher prevalence of GERD, compared with that in the general population, in patients with diabetes mellitus, those with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and those with bronchial asthma. We provide a comprehensive review of GERD in the Japanese population and raise several clinical issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is caused by the abnormal reflux of the gastric contents into the esophagus and is now recognized as a common gastrointestinal (GI) disease in Japan. GERD has a multifactorial pathogenesis, including the presence of gastric acid [1] or bile [2], hiatal hernia [3], lower esophageal sphincter (LES) dysfunction [3, 4], esophageal motility dysfunction [4], impairment of esophageal epithelial resistance [5], and hypersensitivity [6]. Gastric acid in the reflux contents has major harmful effects on the esophageal mucosa and acid-suppressive drugs are effective in most cases of GERD [1]. Because several factors, including Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric atrophy, influence gastric acid secretion, these factors are inversely related to GERD [7]. Impairment of gastroesophageal barrier functions leads to reflux of the gastric contents into the esophagus. Hiatal hernia and transient LES relaxation play a major role in abnormal gastroesophageal reflux (GER) [3, 4]. Defensive factors such as esophageal clearance and epithelial resistance may be involved in the severity of GERD [4, 6].

GERD is diagnosed by esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) and/or the presence of specific symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation. There are several excellent reviews [8–11] of the epidemiology of GERD by Japanese researchers, but most of these studies are reviewed by limited publications, mainly in English. To clarify the situation in Japan, we reviewed articles on the epidemiology of GERD in the Japanese population published in both English and Japanese.

We examined epidemiological studies of GERD in the Japanese population by searching PubMed or Ichushi web in August 2008. Relevant articles were identified using the terms “Japanese” or “Japan” and “heartburn”, “esophagitis”, “GERD”, “non-erosive reflux disease”, or “esophageal ulcer”. We selected the articles (excluding abstracts) on the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in Japan or quoted other older papers in Japanese as needed. We collected and reviewed a total of 120 papers.

We reviewed the epidemiology of reflux esophagitis (erosive esophagitis) and symptomatic GERD in Japan, and the literature showed that the prevalence of GERD has been increasing from the end of the 1990s.

We also discuss GERD in the elderly; asymptomatic GERD; non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and erosive reflux disease, the natural history of GERD; and finally, the prevalence of GERD among patients with specific diseases. However, we excluded postoperative GERD and infant GERD from this review.

Terminology used in GERD diagnosis

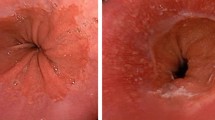

Several diagnostic terms used for GERD may cause some confusion. We define these diagnostic terms (Fig. 1) so that the present review can be better understood. When EGD is used as a diagnostic tool, any positive findings of esophagitis by any classification are defined as “reflux esophagitis” Patients with grade A–D but not grade M by the modified Los Angeles (LA) classification [12] are diagnosed as having “erosive esophagitis” (Fig. 1a). Patients in whom GERD symptoms, such as heartburn, are present, or those who have positive scores in questionnaires specific for GERD are diagnosed as having “symptomatic GERD” (Fig. 1b). When both EGD and GERD symptoms (or questionnaires) are used as diagnostic tools, persons in whom GERD symptoms are present but in whom esophageal mucosal injury is absent are diagnosed as having “non-erosive reflux disease (NERD).” In these cases, grade M by the modified LA classification is included. Persons in whom GERD symptoms are present and who have erosive esophagitis (LA classification grade A or more) are diagnosed as having “erosive reflux disease (ERD)”, and persons with positive findings of esophagitis by EGD but without symptoms are diagnosed has having “asymptomatic ERD” (Fig. 1c).

Definition of diagnostic terminology of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). a Cases diagnosed by esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD). b Cases diagnosed by GERD symptoms or questionnaires. c Cases diagnosed by both EGD and GERD symptoms. LA Los Angeles, ERD erosive reflux disease, NERD non-erosive reflux disease

Prevalence and clinical characteristics of reflux (or erosive) esophagitis in Japan

First, we analyzed GERD in the Japanese population as diagnosed by EGD. There are several classifications of reflux esophagitis but most studies have used the LA classification. Although it was reported that observer variations, dependent on the level of endoscopic experience, occurred during the early period of the introduction of the LA classification to Japan [13], the modified LA classification including grade M [12] has been commonly used more recently for the diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. Grade M is defined as minimal changes to the esophageal mucosa, such as reddish erythema and/or whitish turbidity [12]. Although the definition of reflux esophagitis depends on the individual study, GERD defined as LA classification grade A or more, termed “erosive esophagitis,” could exclude interobserver bias because of the extremely poor agreement in the endoscopic diagnosis of grade M [14, 15].

There were 30 studies [16–45] on the prevalence of reflux esophagitis in outpatients and 12 studies [46–57] on subjects who underwent regular health check-ups (Table 1). The prevalence of reflux esophagitis ranged from 1.4 to 52.1%. This wide range persists even when the studies that included erosive esophagitis (LA classification grade A or more) in their analysis were selected. The reasons for the wide range of reported prevalence for reflux esophagitis might be due to the study subjects (outpatients versus healthy subjects, or their ages), the period when the subjects were enrolled, and the area where the study was conducted. As expected, the prevalence of reflux esophagitis among outpatients was relatively higher than that among subjects who underwent regular health check-ups (mean prevalence for the entire data, 10.6% in outpatients and 7.6% in persons who underwent regular health check-ups).

Twenty-five studies [21, 23, 26–35, 37–41, 43, 44, 48, 52, 55, 56, 58, 59] described the severity of reflux esophagitis according to the LA classification. Because interobserver agreement on grade M is extremely poor, [14, 15] and because the two large studies[29, 30] combined cases of grade C and grade D, and because the LA classification for grade C and grade D was revised in 1999, [60] we analyzed the severity of erosive esophagitis as grade A, grade B, and grade C + D. A total of 9782 cases with erosive esophagitis were analyzed. Of these cases, the numbers with grade A, grade B, and grade C + D were 5338 (54.6%), 3169 (32.4%), and 1275 (13.0%), respectively (Fig. 2). The majority of erosive esophagitis cases in Japan were mild types such as grade A or grade B, accounting for 87%. In the studies which separated grade C and grade D, the prevalence of grade C was more than double that of grade D (grade C, 7.4% and grade D, 3.0%).

Several risk factors for reflux esophagitis have been identified. Most studies agree that the presence of hiatal hernia [17, 18, 22, 29, 34, 46, 48, 52, 55, 56], higher body mass index (BMI) or obesity [29, 37, 45, 51, 55], older age [19, 23, 29, 33, 34, 37, 46], or mild gastric atrophy [33, 34, 37–39, 46, 47, 52, 55, 56], assessed by either higher serum pepsinogen level or closed-type atrophic gastritis by the Kimura-Takemoto classification [61] during EGD, and possibly the absence of H. pylori infection [38, 47, 48] are risk factors for reflux esophagitis. Some studies identified male gender as a risk factor for reflux esophagitis [22, 42, 46, 51, 56, 57] but others failed to find a significant gender difference [19, 52]. Recent interesting studies have shown an association between reflux esophagitis and metabolic syndrome [51, 57], which is recognized as being associated with several GI diseases [62]. Because the H. pylori infection rate is low in younger and middle-aged persons [63], and because most cases of atrophic gastritis are due to H. pylori infection [64], and because the Japanese lifestyle has become increasingly westernized, the risk factors for reflux esophagitis are also changing.

Prevalence and clinical characteristics of symptomatic GERD in Japan

Heartburn is a specific symptom of GERD; however, there are several dilemmas regarding the symptom-based diagnosis of GERD. First, there are differences in the recognition of heartburn among GERD patients. Manabe et al. [65]. showed that, in Japan, recognition of GERD did not differ between patients with erosive esophagitis and physicians, whereas NERD patients did not recognize a “burning sensation in the chest” as heartburn as often as physicians, while confusing “stomach ache” with heartburn. Second, it is uncertain how the frequency and severity of the experienced heartburn influences the diagnosis of GERD. Most researchers agree that GERD can be diagnosed when a person experiences heartburn at least twice weekly and these symptoms disturb their daily life. Disturbance of daily life is usually assessed by administering a questionnaire on health-related quality of life (HR-QOL). Three studies using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36) demonstrated that HR-QOL in GERD patients was lower than that in the general Japanese population. [66–68] A recent study by Hongo et al. [69] using a new questionnaire (QOLRAD) which has been developed as a specific QOL assessment of GERD, showed impairment of HR-QOL in GERD patients.

To achieve an accurate symptom-based diagnosis of GERD, several questionnaires have been established. The Carlsson-Dent self-administered questionnaire (QUEST) [70] has been translated to create a Japanese version. A study by the Osaka GERD Society showed a sensitivity of 72 and 65% and a specificity of 54 and 74% when the cutoff was set at 4 or 6 points, respectively [71]. A frequency scale for symptoms of GERD (FSSG) was recently developed by Kusano et al. [72]. It includes 12 symptoms and uses a 6-point Likert scale. The response scale is designed to measure the frequency of symptoms a patient has experienced (never, occasionally, sometimes, often, and always). When the cutoff was set at 8 points, FSSG showed a sensitivity of 62% and a specificity of 59% [72, 73].

Table 2 presents a summary of the prevalence of symptomatic GERD in Japan [30, 43, 45, 54–57, 74–81]. The diagnosis of symptomatic GERD in ten studies [30, 43, 45, 54, 74–79] was based on the presence of heartburn, while five other studies [55–57, 80, 81] used questionnaires (3 QUEST and 2 FSSG). There were several differences in the diagnostic criteria among the studies, including the frequency, severity, and duration of heartburn; the presence or absence of a detailed explanation of heartburn; face-to-face interview versus self-report questionnaire; and the setting of the cutoff score. The subjects of ten studies [54, 56, 57, 74–80] were an unselected population, mainly persons who underwent regular health check-ups, while in five studies [30, 43, 45, 55, 81] the subjects were outpatients. Although the prevalence of symptomatic GERD ranged from 6.6 to 37.6%, the mean prevalence of GERD was 11.5% (3216/27 870) when GERD was defined as the presence of heartburn at least twice weekly [43, 45, 54, 76–78]. A relatively higher prevalence of GERD was found in a study using a questionnaire. Watanabe et al. [81] showed that patients rarely visited general physicians with heartburn as the chief complaint, although about 37% of patients were positive for FSSG.

Large studies by Yamagishi et al. [79] showed a higher prevalence of symptomatic GERD in elderly women (≥60 years) than men but other studies failed to find a gender difference in terms of the prevalence of symptomatic GERD [75, 76]. Several studies identified that obesity (or weight gain) was a risk for symptomatic GERD [43, 55, 57, 75, 78], and diets containing such foods as sweet cake, rice cake, and fatty or spicy food exacerbated heartburn [43, 56, 75]. Other factors, such as the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or anti-asthmatic drugs [43], irregular lifestyle, overeating, and the presence of stress [54], alcohol intake and smoking habit in male workers [77], and H. pylori infection in younger persons [78] were associated with symptomatic GERD in all the reports.

Recently, functional heartburn was proposed as one of the functional GI disorders [82]. Although the definition of functional heartburn is not well established, the Rome III criteria suggest that functional heartburn is defined as the presence of heartburn but no evidence of abnormal acid reflux and a positive-symptom index by ambulatory 24-h pH monitoring, and no response to treatment with double doses of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) [82]. Therefore, symptomatic GERD might include some cases of functional heartburn. However, it is difficult to distinguish functional heartburn from symptomatic GERD, especially in large studies where it is almost impossible to carry out pH monitoring. Novel biomarkers or diagnostic tools specific for functional heartburn will help us to distinguish these two diseases in the near future.

Increasing prevalence of GERD in Japan

All studies included in Tables 1 and 2 are summarized in Fig. 3 in relation to the study period. The relatively higher prevalence of GERD before 1980 might be due to selection bias and the definition of GERD, but the prevalence of GERD began to increase from the end of the 1990s. Five studies [20, 21, 23, 24, 49] on the prevalence of GERD with study periods of at least 10 years in the same hospitals or area showed a pattern similar to that of the entire data. The precise reasons for the increasing prevalence of GERD in Japan, especially from the end of the 1990s, are unknown. Possible reasons or mechanisms are described below.

Prevalence of GERD in relation to the study period. Fifty-seven studies on the prevalence of GERD were included. Bars show the range of the periods when the subjects were enrolled. Colors represent numbers of study subjects, with blue color indicating less than 100; black 100–5000; and red, more than 5000

Increase in gastric acid secretion

Kinoshita et al. [83] examined gastric acid secretion in Japanese subjects in both the 1970s and 1990s. They found that basal and stimulated gastric acid secretion had increased over the past 20 years in both the elderly and non-elderly, irrespective of H. pylori infection. Since gastric acid plays a major role in the pathogenesis of GERD, an increase in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese affects the epidemiology of GERD.

Decrease in H. pylori infection rates

The prevalence of H. pylori infection is higher in Japan compared with western countries but the rate of infection is decreasing. Sugiyama et al. [63] showed that H. pylori seropositivity was 74.9% in asymptomatic subjects born before 1950 and 20.7% in those born after 1950 in the general population. Because H. pylori infection is inversely related to GERD, a decrease in the infection rate is associated with an increasing prevalence of GERD in the Japanese population, especially in younger and middle-aged persons.

More attention being paid to GERD

There are three PPIs available in Japan. Omeprazole, lansoprazole, and rabeprazole appeared on the market in 1991, 1992, and 1997, respectively. The increasing use of PPIs in the clinical field has led to a greater recognition of GERD. The number of manuscripts, reviews, and themes of symposia related to GERD began increasing in the 1990s. Especially, the first large epidemiological study, published in 1999, [29] which is the most cited Japanese paper in this field, had an influence on Japanese gastroenterologists. Finally, the Japanese GERD Society was established in 1996 and the number of members is increasing. These factors have led to Japanese doctors paying more attention to GERD.

Advance in the concept of GERD

The modified LA classification has been commonly used for the diagnosis of GERD. Although a consensus about the diagnosis of grade M has yet to be reached, an expanded concept of GERD including NERD could affect the reported increase in GERD prevalence. This is further supported by advances in videoendoscopy, enabling the detection of minimal esophageal changes or tiny superficial esophageal mucosal injuries.

Proportions and clinical characteristics of NERD and ERD in Japan

GERD is divided into two subtypes, NERD and ERD, characterized by the presence (ERD) or absence of breaks in the mucosa (NERD). Ten studies [40, 43–45, 54–58, 84] show the proportions of NERD and ERD in GERD. The subjects of three studies [54, 56, 57] were persons who underwent regular health check-ups, while the subjects of the other studies [40, 43–45, 55, 58, 84] were outpatients. Figure 4 shows the proportions of NERD and ERD in Japan. Among a total of 5022 subjects, NERD was identified in 2944 (58.6%) and ERD in 2078 (41.4%). A higher proportion of NERD among GERD patients was more prominent in the unselected subjects who underwent routine health check-ups, with 1205 (80.4%) of 1490 subjects with GERD. Several studies showed that NERD was found more frequently in females [54–58, 84] and in younger persons [55], and was associated with the absence of hiatal hernia [54, 56, 58, 84], and with lower BMI [54, 56–58, 84] compared with ERD among subjects with GERD. These clinical characteristics of NERD are also found in western countries; however, more severe gastric atrophy [54, 56, 84] and the higher rate of H. pylori infection [84] compared with ERD are specific characteristics of Japanese NERD. Joh et al. [68] demonstrated that the frequency of abnormal acid reflux with NERD was higher in patients with minimal changes than in patients without such changes. Thus, if gastric acid secretion lead to the development of NERD (grade M or grade N) or ERD, these clinical features found in Japanese NERD could agree with the theoretically advanced features. Other factors, such as smoking habit [55, 58, 84] or a low incidence of metabolic syndrome [57] are also suggested. The clinical characteristics of ERD are virtually the same as those of reflux esophagitis. Finally, as we mentioned above, the possibility that functional heartburn is included in NERD should be noted.

GERD in elderly Japanese

We should discuss the epidemiology and clinical features of GERD in the elderly because Japan is known for the longevity of its people. Several studies showed a higher prevalence of GERD in the elderly, and the clinical characteristics in this group. First, GERD is predominant in females [85–88]. Women in Japan live longer than men (mean lifespan in 2006 was 85.8 years for women and 79.0 years for men according to a report from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [89]) and osteoporosis and kyphosis commonly found in elderly women may be a factor in the higher prevalence of GERD in elderly women [90]. In addition, Kusano et al. [91] demonstrated that the presence of kyphosis correlated with hernia size in elderly women. Second, the proportion of severe esophagitis is high in the elderly [27, 29, 59, 92]. Furukawa et al. [29] showed that severe esophagitis was found in women more than 70 years old and in men more than 80 years old. The mechanisms responsible for the higher proportion of severe esophagitis in the elderly are unknown, but impairment of esophageal motility in the elderly [92, 93] might be a factor. Third, the presence of hiatal hernia is a risk factor for GERD in both the elderly and non-elderly, but the incidence (46–72%) of hiatal hernia in the elderly is extremely high [27, 29, 87, 92–94], especially in women [29]. In addition, the prevalence of hiatal hernia increases with age [95]. Fourth, Ohara et al. [96] demonstrated that the rate of H. pylori infection in elderly GERD subjects was lower (39%) than that in elderly non-GERD subjects (63%).They found that the serum pepsinogen I/II ratio in elderly GERD subjects was significantly higher than that in elderly non-GERD subjects, revealing mild gastric atrophy, [96] although Urita et al. [85, 86] showed that the incidence of open-type atrophic gastritis was higher in elderly GERD subjects compared with non-elderly GERD subjects. Because the H. pylori infection rate and the presence or severity of gastric atrophy increases with age, clearer associations between GERD and H. pylori-negative or mild gastric atrophy appear in the elderly [85, 86, 96]. Finally, it is a clinically important issue that 24–54% of elderly GERD patients are asymptomatic [27, 86, 87], especially those with mild esophagitis [27]. Sometimes GI bleeding such as hematemesis or tarry stool is the first episode seen in the elderly, accounting for 13.7–33.3% [86–88]. Although GERD is rarely (1.2%) seen as a cause of upper GI bleeding in emergency endoscopy units [26], clinicians should consider that GERD is a potential differential diagnosis in cases of acute GI bleeding in elderly Japanese.

Asymptomatic ERD in Japan

As described above, asymptomatic ERD is one of the clinical features in elderly GERD subjects; thus, we reviewed asymptomatic ERD in the general adult population, with results reported in this section. Individuals often experience asymptomatic erosive esophagitis, which is frequently found incidentally during regular health check-ups or upon further examination for other reasons during an EGD examination. Two large studies showed that 144 (73.8%) out of 195 subjects with erosive esophagitis (LA grade ≥ A) were asymptomatic when assessed by QUEST (cutoff score 6) [56], and 288 (58.8%) of 490 subjects with erosive esophagitis (LA grade ≥ A) were asymptomatic when this was defined as less than two episodes of heartburn per week [54]. The high prevalence of asymptomatic ERD might be due to the definition of asymptomatic (high cutoff score on QUEST and high frequency of heartburn) or the study subjects (persons undergoing a regular health check-up). Nozu and Komiyama [59] demonstrated that 23 (26.4%) of 87 outpatients with erosive esophagitis were asymptomatic when this was defined as the absence of either typical symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation, or atypical symptoms such as epigastric pain, discomfort, dysphagia, cough, or globus. They also found that smoking habit, male gender, and lower BMI were independent risk factors for asymptomatic ERD [59]. Further study of whether these factors are actually associated with asymptomatic ERD is required because of the small sample size of the Nozu study. In addition, no detailed natural history of asymptomatic ERD exists.

Natural history of GERD in Japan

Three questions about the natural history of GERD are suggested: (1) How often do non-GERD subjects develop GERD? (2) Is there a natural sequence of NERD-mild esophagitis-severe esophagitis among GERD patients? (3) How often do GERD patients develop (or progress) to Barrett’s esophagus? A few studies have provided information on the natural history of GERD in the Japanese population.

Three studies demonstrated the incidence of GERD development among non-GERD subjects. Miyamoto et al. [97] showed 37 (15.4%) of 241 elderly subjects developed GERD as diagnosed by QUEST during a 6-year follow-up period, and they identified absence of H. pylori infection, constipation, and the use of calcium-channel antagonists as risk factors for the development of GERD. Similarly Azumi et al. [98] reported 35 (8%) of 451 subjects (mean age, 47 years) who developed GERD during a 5-year follow-up period. Kawanishi [99] demonstrated that 51 (11.3%) of 450 subjects (mean age, 48.0 years) developed erosive esophagitis (47 with grade A and 4 with grade B) during a 5-year follow-up period. These studies suggest that about 10% of non-GERD adults go on to develop GERD, with this being more frequent in the elderly. Azumi et al. [98] demonstrated that 65 (74%) out of 88 subjects who were QUEST-positive at initial examination became QUEST-negative after 5 years, suggesting that, there are some GERD populations who improve spontaneously. Because GERD goes through a cycle of remission and recurrence, there are some difficulties in defining precisely what constitutes a new development of GERD.

Kawanishi [99] elucidated the natural history of NERD as diagnosed by the occurrence of heartburn at least twice weekly without breaks in the esophageal mucosa. He found that 17 (36.2%) of 47 NERD patients developed erosive esophagitis, including 15 with grade A and 2 with grade B esophagitis during a 5-year follow-up period [99]. The incidence of esophagitis was higher compared with that in non-NERD subjects (11.3%), and the absence of H. pylori infection, the absence of gastric atrophy, an increase in BMI, and elevated triglycerides were risk factors for the development of erosive esophagitis among NERD subjects. An impressive study by Manabe et al. [100] elucidated the natural history of mild esophagitis including grade A and grade B. Using EGD, they followed 105 patients with mild esophagitis for 5 years. Only 11 (10.5%) of 105 progressed to severe esophagitis, including 9 with grade C and 2 with grade D, while esophagitis resolved in 31, and 63 showed no progression of esophagitis. They identified increased age, female gender, GERD symptoms at initial examination, the presence of hiatal hernia, the absence of gastric atrophy, and the absence of H. pylori infection as risk factors for progression of esophagitis.

Limited available data about the natural history of GERD in the Japanese population suggest that a subpopulation, especially those who are H. pylori-negative or those in whom gastric atrophy is absent, progress to more severe types of GERD, but the rate of such progression may be low. The rate of progression to Barrett’s esophagus in Japanese GERD patients is still unknown.

Association between peptic ulcer disease and reflux esophagitis

A strong association between peptic ulcer disease and reflux esophagitis had been reported in Japan before the H. pylori era. Table 3 shows the co-incidence of peptic ulcer diseases among patients with reflux esophagitis [18–23, 25, 101, 102]. Co-incidence of duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and duodenogastric ulcer was found in 9.6–31.6%, 6.0–20.1%, and 3.5–5.4% of patients with reflux esophagitis, respectively. The high co-incidence of peptic ulcer diseases might be due to the high prevalence of peptic ulcer disease in Japan before the H. pylori era. The presence of duodenal ulcer might be related to the hypersecretion of gastric acid and/or delay in gastric emptying because of stenosis due to edema or deformity of the duodenal bulb. Interestingly, Amano et al. [41] demonstrated that elderly patients (65 years or older) with duodenal ulcer or distal gastric ulcer had a significantly higher prevalence of reflux esophagitis, including LA grade M (33.3 and 31.7%, respectively), than those with proximal gastric ulcer (18.0%), but these differences were not observed among younger patients. This finding might be related to the role of hypersecretion of gastric acid in elderly GERD patients. Because H. pylori eradication therapy is the first-line treatment for peptic ulcer disease and prevents ulcer recurrence, the rate of co-incidence of peptic ulcer diseases in patients with reflux esophagitis has been decreasing. Associations between reflux esophagitis and NSAID- or aspirin-induced duodenogastric ulcer are unknown. The effects of H pylori eradication therapy on pre-existing GERD are discussed below.

GERD and Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan

An elegant systematic review by Nakajima and Hattori [103] is useful in understanding how GERD is related to H. pylori therapy. There are two proposed issues including recurrence of GERD after cure of infection and the effect of eradication therapy on pre-existing GERD.

The development of reflux esophagitis was found in 4.8–20.5% after cure of infection (Table 4) [104–110]. Most of the newly developed reflux esophagitis was mild type. Two studies [104, 109] revealed a higher incidence of reflux esophagitis in patients with successful eradication compared with those with persistent infection (failure of eradication or matched control) but one study showed no difference [105]. The relatively wide range of incidence might be due to the study subjects (patients with duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, or other diseases) or the observation periods established to detect the development of GERD. Several reports suggested that the presence of hiatal hernia, corpus gastritis, and an increase in gastric acidity were risk factors for development of reflux esophagitis after cure of infection [104, 109]. Several mechanisms for the increased gastric acidity after cure of infection, such as a decrease in ammonia production, cytokines or hormones, and recovery of gastric inflammation of the corpus have been suggested. Whether an increase in gastric acidity alone is responsible for the development of GERD is unclear because of the lack of detailed associations between H. pylori infection and gastroesophageal barriers such as LES. Sasaki et al. [111] reported on the long-term observation of 45 patients with reflux esophagitis (all mild esophagitis such as grade A or grade B) that developed after H. pylori eradication. They found improvement in 78.8%, worsening in 8.9%, and no progression to severe type (grade C or grade D) 3 years after eradication. These findings suggest that most cases of newly developed GERD after H. pylori eradication are transient phenomena and eradication therapy rarely becomes a long-term clinical problem.

Murai et al. [105] showed that 4.6% of patients with successful H. pylori eradication had a recurrence of GERD symptoms after eradication. Yamamori et al. [110] demonstrated that approximately 10% of patients with peptic ulcer disease redeveloped GERD symptoms after cure of H. pylori infection, and age more than 70 years and gastric ulcer were associated with the recurrence. However, the development of GERD symptoms is complex because these symptoms were masked during anti-ulcer treatment such as by the administration of acid-suppressive drugs [103]. In addition, heartburn is seen in patients with other diseases, especially in those with functional dyspepsia. Thus, which disease (GERD or functional dyspepsia) appears after the cure of H. pylori infection in patients with peptic ulcer disease could not be distinguished.

The effect of H. pylori eradication therapy on pre-existing GERD in Japanese patients is summarized in Table 5 [105, 106, 112, 113]. Four studies of the effect of H. pylori eradication therapy on pre-existing GERD have been conducted in Japan. These studies suggest improvement of reflux esophagitis and GERD symptoms after cure of H. pylori infection. In particular, two studies, by Miwa et al. [112]. and Ishiki et al. [113], demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in GERD in a group cured of infection compared with a group with persistent infection. Ishiki et al. [113] found that duodenal ulcer, cure of H. pylori infection, the absence of hiatal hernia, and lower BMI were independently associated with improvement of reflux esophagitis after H. pylori eradication. How does cure of H. pylori infection improve GERD? There are several proposed mechanisms. First, normalization of gastric acidity in patients with duodenal ulcer [114] might play an important role. Second, as Nakajima and Hattori [103] suggested, symptoms such as heartburn and/or acid regurgitation are directly related to peptic ulcer disease; thus, symptoms are improved after the cure of H. pylori infection. Third, peptic ulcer disease, especially duodenal ulcer, is known to be co-incident with GERD (as described in the section above). If peptic ulcer itself directly or indirectly induces reflux esophagitis, healing of the ulcer results in improvement of GERD.

Prevalence of GERD in patients with specific diseases

We reviewed the prevalence of GERD in Japanese patients with specific diseases, including diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), and bronchial asthma. We selected these diseases because there was a sufficient number of publications to review. Other diseases such as collagen disease and osteoporosis are well known as having a high co-incidence with GERD but were excluded in this review because few such Japanese epidemiological studies have been conducted. Non-cardiac chest pain, chronic cough, laryngitis, and dental disease, which are strongly associated with GERD [115], were excluded for the same reason.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is common in Japanese adults, and diabetic patients often complain of GI symptoms. Because diabetes mellitus and GERD share similar risk factors such as obesity, and because diabetes mellitus affects autonomic nerve functions, a higher prevalence of GERD is to be expected in diabetic patients. Table 6 summarizes the prevalence of GERD in patients with diabetes mellitus [116–121]. Nishida et al. [117] demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of GERD in diabetic patients compared with controls, but Ariizumi et al. [121] showed no difference in the prevalence of reflux esophagitis between diabetic patients and controls. When QUEST was used for the diagnosis of GERD [116–121], about 30% of diabetic patients were positive for GERD, showing a higher rate compared with the general adult population (see Table 2). Several studies showed that disease duration of diabetes [117, 120] and the presence of diabetic neuropathy [119, 120] were associated with GERD. Because esophageal motility disorder and abnormal acid reflux in diabetic patients are associated with diabetic motor neuropathy [122] and such esophageal dysfunction is worsened with long disease duration [123], esophageal dysfunction may result in a higher prevalence of GERD in diabetic patients. On the other hand, Kirizuka et al. [116] reported that the presence of hiatal hernia or the use of calcium-channel antagonists was more closely related to the incidence of GERD in diabetic patients than the duration or control of diabetes. Additional associated factors such as an increase in BMI or HbA1c level [117], the use of oral hypoglycemic agents [117], or constipation [119] were suggested as factors related to GERD incidence.

There is another important issue concerning GERD in diabetic patients. Kinekawa et al. [124] examined 53 diabetic patients by QUEST immediately before 24-h pH monitoring. They found that diabetic patients had fewer symptoms and extremely low scores, and there was no difference in scores between patients with and without GER. Similarly, Hisano et al. [119] showed that diabetic patients with GERD had fewer symptoms than nondiabetic GERD patients. If GERD symptoms are masked in diabetic patients, the precise prevalence of GERD might actually be higher.

Chronic liver disease

Six studies [117, 125–129] have reported an association between GERD and chronic liver disease (Table 7). First, Akatsu et al. [125] demonstrated that 8 (27.6%) of 29 patients developed reflux esophagitis after living-donor liver transplantation, although only 1 patients had reflux esophagitis before transplantation. The mechanisms of GERD development after living-donor liver transplantation are still unknown. The other five studies [117, 126–129] showed the prevalence of GERD in patients with chronic liver disease using specific questionnaires such as QUEST or FSSG. Two studies[126, 128] showed a significantly higher prevalence of GERD (approximately 19%) in liver disease patients compared with controls, but the prevalence of GERD in controls was extremely low compared with that in the general adult population (see Tables 1, 2). Only one report, by Suzuki et al. [129] using QUEST, showed that more than 30% of patients with chronic liver disease had GERD. Thus, we could not conclude that the prevalence of GERD in Japanese patients with chronic liver disease was high. Most authors showed no differences in GERD prevalence according to the etiology or stage (chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis) of liver disease [126, 128, 129], but Ueda et al. [127] showed a relatively higher incidence of GERD in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Because drinking alcohol worsens or induces GERD symptoms, and because non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and GERD share common risk factors, such as metabolic syndrome [62], their associations might be examined in future. Because interferon affects gastric emptying [130], such antiviral therapy might affect the pathogenesis of GERD. Researchers should examine in more detail the associations between GERD and chronic liver disease. Clinically, erosive esophagitis is believed to be a risk factor for the rupture of esophageal varices. A recent study by Okamoto et al. [131]. showed that the positive predictor for bleeding from esophageal varices was the presence of a red color sign in the right anterior wall of the esophagus, where mucosal breaks induced by GERD were more frequently found, and the administration of a PPI was a negative predictor. These findings might explain an association between GERD and rupture of esophageal varices, but further study of this is needed.

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS)

Suganuma et al. [132] first found a significant increase in the incidence of sleep disturbance in Japanese OSAS patients with GERD compared with OSAS patients without GERD. Subsequently, six studies [133–138] on the associations between GERD and OSAS were reported (Table 8). The prevalence of GERD in OSAS patients was reported to be 19.2–42.1%. Uchiyama et al. [133], using 24-h pH monitoring, demonstrated no significant difference in GERD prevalence between sleep disturbance patients with OSAS, defined as a score on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 5 or more, and non-OSAS, defined as AHI scores of less than 5 (19.2% in OSAS patients and 15.4% in non-OSAS patients), while the other studies [134–138] showed a higher prevalence, compared with the findings of Uchiyama et al. [133]. Tanaka et al. [137] showed a significant association between the prevalence of GERD and the severity of OSAS as assessed by AHI score, but Tanimura et al. [136] showed no such association. Three studies [133, 135, 138] demonstrated that nasal continuous positive airway pressure improved OSAS as well as GERD, but the sample size was small and the effect of GERD therapy, such as a PPI, on the improvement of OSAS was not reported in Japan. As shown in a review by Mizuta et al. [139], the association between GERD and OSAS remains controversial in Japan, as well as worldwide, because of failure to establish a causal link between the two diseases in a large study, inconsistencies in definition, similar risk factors for the two diseases (such as obesity), and several biases. However, the high prevalence of GERD in OSAS patients in Japan should be noted.

Bronchial asthma

Bronchial asthma is one of the four extra-esophageal syndromes strongly associated with GERD in the Montreal definition and classification [115]. There are several proposed mechanisms of association between bronchial asthma and GERD. Vagally mediated reflex and microaspiration worsens asthma, while autonomic nerve disturbance and the use of bronchodilators affect GERD. Ten papers [43, 140–148] identified an association between GERD and bronchial asthma, and most studies focused on the prevalence of GERD in asthmatics. Although the diagnostic criteria for GERD were different among these studies, the prevalence of GERD in asthmatics was high, ranging from 22.1 to 75.6% (Table 9). Several studies showed the efficacy of PPIs in the treatment of GERD and improvement of pulmonary function or asthma symptoms in asthmatic patients. PPIs attenuated GERD symptoms as well as asthma symptoms, but the efficacy of PPIs in improving pulmonary function remains controversial; improvement of peak expiratory flow was shown in three studies [142, 143, 145], but no change was observed in two studies [146, 147]. A further large study is needed. Although data are limited concerning the prevalence of asthma in GERD patients, the use of bronchodilators was reported to be significantly higher in persons with heartburn compared with those without heartburn [43].

In conclusion, we have provided a comprehensive review of the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. Several factors are associated with the increase in the prevalence of GERD in Japan. Especially, H. pylori infection, gastric atrophy, and long life affect the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population at the present time.

References

Kinoshita Y, Adachi K, Fujishiro H. Therapeutic approaches to reflux disease, focusing on acid secretion. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(suppl 15):13–9.

Osugi H, Higashino M, Kaseno S, Takada N, Takemura M, Ueno M, et al. Ambulatory intraesophageal bilirubin monitoring in Japanese patients with gastroesophageal reflux. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:697–702.

Mittal RK. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux: motility factors. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(suppl 15):7–12.

Iwakiri K, Sugiura T, Hayashi Y, Kotoyori M, Kawakami A, Makino H, et al. Esophageal motility in Japanese patients with Barrett’s esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1036–41.

Yoshida N, Yoshikawa T. Defense mechanism of the esophageal mucosa and esophageal inflammation. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(suppl 15):31–4.

Miwa H, Minoo T, Hojo M, Yaginuma R, Nagahara A, Kawabe M, et al. Oesophageal hypersensitivity in Japanese patients with non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 1):112–7.

Suzuki H, Hibi T, Marshall BJ. Helicobacter pylori: present status and future prospects in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1–15.

Hongo M, Shoji T. Epidemiology of reflux disease and CLE in East Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(suppl 15):25–30.

Fujimoto K. Review article: prevalence and epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 8):5–8.

Wong BC, Kinoshita Y. Systematic review on epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:398–407.

Kouzu T, Hishikawa E, Watanabe Y, Inoue M, Satou T. Epidemiology of GERD in Japan (in Japanese). Nippon Rinsho. 2007;65:791–4.

Kusano M, Ino K, Yamada T, Kawamura O, Toki M, Ohwada T, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver variation in endoscopic assessment of GERD using the “Los Angeles” classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:700–4.

Hoshihara Y, Hashimoto M. Endoscopic classification of reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Nippon Rinsho. 2000;58:1808–12.

Amano Y, Ishimura N, Furuta K, Okita K, Masaharu M, Azumi T, et al. Interobserver agreement on classifying endoscopic diagnoses of nonerosive esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1032–5.

Miwa H, Yokoyama T, Hori K, Tanimura M, Honda Y, Isozaki K, et al. Interobserver agreement in endoscopic evaluation of reflux esophagitis using a modified Los Angeles classification incorporating grades N and M: a validation study in a cohort of Japanese endoscopists. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:355–63.

Endo M, Kobayashi S, Suzuki H, Takemoto T, Nakayama K. Diagnosis of early esophageal cancer. Endoscopy. 1971;2:61–6.

Makuuchi H. Clinical study of sliding esophageal hernia with special reference to the diagnostic criteria and classification of the severity of the disease (in Japanese). Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1982;79:1557–67.

Yoshimori M, Yamashita S, Suzuki S, Fukutomi H, Oguro Y, Doi H, et al. Esophagitis, peptic ulcer, and gastric acidity (in Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc. 1975;17:714–8.

Furuya S, Kodama T, Takaaki J, Fukui Y, Fujita S, Maeda T, et al. Epidemiology of reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Shoukakika. 1994;19:357–65.

Tsuchiya H, Takasu S. Epidemiology (in Japanese). In: Tsuneoka K, editor. Reflux esophagitis. Tokyo: Bunkoudou; 1988. p. 101–9.

Sakurai Y. Retrospective analysis of 2431 cases of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) diagnosed by panendoscopy (in Japanese). Stomach Intest. 1999;34:963–9.

Kuma E, Kato T, Sakanishi Y, Nakagawa H, Kagaya T, Tomori G, et al. A clinical study of the reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Tama Symp J Gastroenterol. 1991;5:48–53.

Yamaguchi Y, Sakurai Y, Ohyama T, Yamamura F, Terada M, Itoh M, et al. Clinical epidemiological study of GERD with Los-Angeles classification (in Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc. 1998;40:1138–44.

Keida Y, Yamaguchi Y, Shinjou M, Shimabukuro Y, Shinoura Y, Kikuchi K. Study of reflux esophagitis and hiatal hernia at Okinawa prefectural Chubu Hospital (in Japanese). Okinawa Igakukai Zasshi. 2005;43:34–8.

Arizawa K, Kawaguchi S, Yonezawa T, Doi M, Mizuno W, Mautmoto T, et al. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc. 1992;34:1008–16.

Yamaguchi M, Iwakiri R, Yamaguchi K, Mizuta T, Shimoda R, Sakata Y, et al. Bleeding and stenosis caused by reflux esophagitis was not common in emergency endoscopic examinations: a retrospective patient chart review at a single institution in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:265–9.

Maekawa T, Kinoshita Y, Okada A, Fukui H, Waki S, Hassan S, et al. Relationship between severity and symptoms of reflux oesophagitis in elderly patients in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:927–30.

Tomiyama R, Miyasato S, Chinen T, Maeda K, Fukuchi A, Sugama R, et al. Clinical study of reflux esophagitis at Miyako area in Okinawa (in Japanese). Okinawa Igakkai Zassi. 2001;39:19–21.

Furukawa N, Iwakiri R, Koyama T, Okamoto K, Yoshida T, Kashiwagi Y, et al. Proportion of reflux esophagitis in 6010 Japanese adults: prospective evaluation by endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:441–4.

Okamoto K, Iwakiri R, Mori M, Hara M, Oda K, Danjo A, et al. Clinical symptoms in endoscopic reflux esophagitis: evaluation in 8031 adult subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2237–41.

Sakamoto H, Goto A, Nakagawa T, Nagano K, Mihara F, Mugikura S. The study of reflux esophagitis in Hakodate district (in Japanese). Dounan Igaku Kaishi. 2001;35:364–7.

Kawai T, Koguma K, Kudou T, Umezawa H, Hagiwara S, Morita S, et al. Prevalence of reflux esophagitis and study of refractory reflux esophagitis in our hospital (in Japanese). Tama Symp J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:22–9.

Iwakiri K, Tanaka Y, Hayashi Y, Kotoyori M, Kawami N, Kawakami A, et al. Association between reflux esophagitis and/or hiatus hernia and gastric mucosal atrophy level in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:2212–6.

Inamori M, Togawa J, Nagase H, Abe Y, Umezawa T, Nakajima A, et al. Clinical characteristics of Japanese reflux esophagitis patients as determined by Los Angeles classification. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:172–6.

Inaba T, Kawai K, Kobara H, Miyatake H, Morimoto N, Hiratsuka I, et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire (QUEST) in the assessment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (in Japanese). J New Rem Clin. 1999;48:1277–89.

Ohta M, Kikuchi T, Shigematsu K, Suzuki T, Nakamura A, Okamoto F, et al. A study on endoscopic findings of reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus (in Japanese). Tama Symp J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:10–3.

Morichika K, Hashimoto T, Kusano M, Hosoda S, Kuramoto T, Tamura K, et al. Association of obesity with reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Juntendo Med J. 2005;51:83–9.

Sekiguchi T, Ohwada T, Hagihara O, Kimura M. Prevalence of reflux esophagitis in 2000 (in Japanese). Nippon Rinshou Naika Ikai Zassi. 2005;20:393–402.

Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, et al. Association between gastroesophageal flap valve, reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s epithelium, and atrophic gastritis assessed by endoscopy in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:533–9.

Nagoshi A, Zai H, Harasawa S. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;7:441–4.

Amano Y, Komazawa Y, Ishimura N, Fujishiro H, Ishihara S, Adachi K, et al. Prevalence of reflux esophagitis in patients with duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:514–5.

Shimazu T, Matsui T, Furukawa K, Oshige K, Mitsuyasu T, Kiyomizu A, et al. A prospective study of the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and confounding factors. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:866–72.

Ohara S, Kouzu T, Kawano T, Kusano M. Nationwide epidemiological survey regarding heartburn and reflux esophagitis in Japanese (in Japanese). Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;102:1010–24.

Nagoshi A, Kusano M, Harasawa S. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;10:431–5.

Sakaguchi M, Oka H, Hashimoto T, Asakuma Y, Takao M, Gon G, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for GERD in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:57–62.

Amano K, Adachi K, Katsube T, Watanabe M, Kinoshita Y. Role of hiatus hernia and gastric mucosal atrophy in the development of reflux esophagitis in the elderly. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:132–6.

Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, Okamoto M, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, et al. Inverse background of Helicobacter pylori antibody and pepsinogen in reflux oesophagitis compared with gastric cancer: analysis of 5732 Japanese subjects. Gut. 2001;49:335–40.

Fujishiro H, Adachi K, Kawamura A, Katsube T, Ono M, Yuki M, et al. Influence of Helicobacter pylori infection on the prevalence of reflux esophagitis in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1217–21.

Uetake T, Shibata N, Osawa A, Ishikawa M, Kobayashi M, Kojima Y, et al. Changes in incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) over 10 years in an aging district and its characteristics (in Japanese). Shoukakika. 2000;30:139–43.

Sekiguchi T, Horikoshi T. Pathogenesis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (in Japanese). Jpn Med J. 1997;3830:1–5.

Moki F, Kusano M, Mizuide M, Shimoyama Y, Kawamura O, Takagi H, et al. Association between reflux oesophagitis and features of the metabolic syndrome in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1069–75.

Nakamura T, Kitahara F, Ohtsuka H, Kojima Y, Sato T, Enomoto N, et al. Prevalence and relationship of Barrett’s mucosa, reflux esophagitis, hiatal hernia and atrophic gastritis (in Japanese). Shoukakiaka. 2005;41:10–5.

Furuta K, Adachi K, Arima N, Yagi J, Tanaka S, Miyaoka Y, et al. Study of arteriosclerosis in patients with hiatal hernia and reflux esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1732–6.

Yagi N, Arai M, Fujimoto S. Importance of lifestyle advice in the management of endoscopically negative gastroesophageal reflux disease patients in Japan (in Japanese). Shoukakaika. 2006;43:194–201.

Kobayashi T, Yoshino J, Wakabayashi T, Inui K, Okushima K, Miyoshi H, et al. Study of the characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux disease (NERD, in particular) as discovered in a mass survey (in Japanese). J Gastroenterol Cancer Screen. 2006;44:283–91.

Mishima I, Adachi K, Arima N, Amano K, Takashima T, Moritani M, et al. Prevalence of endoscopically negative and positive gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1005–9.

Funatsu K, Tomai K, Kurihara K, Homma M, Yamashita T, Hosoai K, et al. A clinical study on erosive and non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease in health check-up subjects (in Japanese). Ningen Dock. 2008;22:811–7.

Miwa H, Sasaki M, Furuta T, Koike T, Habu Y, Ito M, et al. Efficacy of rabeprazole on heartburn symptom resolution in patients with non-erosive and erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a multicenter study from Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:69–77.

Nozu TH. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:27–31.

Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–80.

Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1963;3:87–97.

Watanabe S, Hojo M, Nagahara A. Metabolic syndrome and gastrointestinal diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:267–74.

Sugiyama T, Nishikawa K, Komatsu Y, Ishizuka J, Mizushima T, Kumagai A, et al. Attributable risk of H. pylori in peptic ulcer disease: does declining prevalence of infection in general population explain increasing frequency of non-H. pylori ulcers? Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:307–10.

Asaka M, Sugiyama T, Nobuta A, Kato M, Takeda H, Graham DY. Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in Japan: results of a large multicenter study. Helicobacter. 2001;6:294–9.

Manabe N, Haruma K, Hata J, Kamada T, Kusunoki H. Differences in recognition of heartburn symptoms between Japanese patients with gastroesophageal reflux, physicians, nurses, and healthy lay subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:398–402.

Wada T, Sasaki M, Kataoka H, Tanida S, Itoh K, Ogasawara N, et al. Efficacy of famotidine and omeprazole in healing symptoms of non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: randomized-controlled study of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(suppl 2):2–9.

Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Nebiki H, Chono S, Uno H, Kitada K, et al. Famotidine versus omeprazole: a prospective randomized multicentre trial to determine efficacy in non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(suppl 2):10–8.

Joh T, Miwa H, Higuchi K, Shimatani T, Manabe N, Adachi K, et al. Validity of endoscopic classification of nonerosive reflux disease. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:444–9.

Hongo M, Kinoshita Y, Shimozuma K, Kumagai Y, Sawada M, Nii M. Psychometric validation of the Japanese translation of the quality of life in reflux and dyspepsia questionnaire in patients with heartburn. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:807–15.

Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E, Johnsson F, Junghard O, Lauritsen K, et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:1023–9.

Nagano K, Kubo M, Goto M, Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Kanda T, et al. The diagnosis of GERD: a study of a questionnaire (QUEST) for patients complaining of upper gastrointestinal symptoms (in Japanese). J New Rem Clin. 1998;47:841–51.

Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Sugimoto S, Kawamura O, Maeda M, Minashi K, et al. Development and evaluation of FSSG: frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:888–91.

Shimoyama Y, Kusano M, Sugimoto S, Kawamura O, Maeda M, Minashi K, et al. Diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease using a new questionnaire. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:643–7.

Stanghellini V. Three-month prevalence rates of gastrointestinal symptoms and the influence of demographic factors: results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;231(suppl):20–8.

Kato K, Kodama T, Fujita S, Kashima K, Sano A, Sakagami K. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a questionnaire-based survey of heartburn symptoms. In: Matsuo Y, Kasuya Y, Muto T, Tsuchiya M, editors. Gastrointestinal function. Regulation and disturbance, vol. 15. Tokyo: Excepta Medica; 1977. p. 69–75.

Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Watanabe Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:26–9.

Watanabe Y, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, et al. Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japanese men. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:807–11.

Kubota E, Tanida S, Sasaki M, Kataoka H, Oshima T, Ogasawara N, et al. Contribution of Helicobacter pylori infection and obesity on heartburn in a Japanese population. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2006;39:168–73.

Yamagishi H, Koike T, Ohara S, Kobayashi S, Ariizumi K, Abe Y, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in a large unselected general population in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1358–64.

Sudou H, Tanaka Y, Kurai A, Namiki K, Miyake Y, Yamada F, et al. The usefulness of QUEST questionnaire and PPI test in the assessment of GERD in clinical practice (in Japanese). Nippon Rinsho Naika Ikai Zassi. 2007;22:71–5.

Watanabe T, Urita Y, Sugimoto M, Miki K. Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms are more common in general practice in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4219–23.

Galmiche JP, Clouse RE, Bálint A, Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ, Paterson WG, et al. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1459–65.

Kinoshita Y, Kawanami C, Kishi K, Nakata H, Seino Y, Chiba T. Helicobacter pylori independent chronological change in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese. Gut. 1997;41:452–8.

Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Shiba M, Yamamori K, Watanabe Y, Sasaki E, et al. Differences in clinical characteristics between patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease and erosive esophagitis in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:754–8.

Urita Y, Nishino S, Koyama H, Kondo E, Yamada S, Ozaki M, et al. Reflux esophagitis in the elderly (in Japanese). J Geriatr Gastroenterol. 1997;9:85–9.

Urita Y, Miki K. Reflux esophagitis in the elderly (in Japanese). Clinica. 1998;25:257–61.

Tanimura H, Kubo M, Kawano S. Clinical study of reflux esophagitis in the elderly (in Japanese). Ther Res. 1999;20:2297–9.

Watabe H, Sasaki S, Andachi H, Sasaki H. Examination of patients aged 80 years and older with reflux esophagitis at Hirose Municipal Hospital (in Japanese). Nippon Kourei Shoukaki Igakkai Zassi. 2001;3:92–7.

http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/life/life06/index.html.

Fujimoto K, Iwakiri R, Okamoto K, Oda K, Tanaka A, Tsunada S, et al. Characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Japan: increased prevalence in elderly women. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(suppl 15):3–6.

Kusano M, Hashizume K, Ehara Y, Shimoyama Y, Kawamura O, Mori M. Size of hiatus hernia correlates with severity of kyphosis, not with obesity, in elderly Japanese women. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:345–50.

Furuya S, Yamashita S, Takaaki J, Fukui Y, Fukuda S, Kodama T. The characteristics of reflux esophagitis of the aged group (in Japanese). Shoukakika. 1992;16:15–23.

Sakakibara K, Harasawa S, Miwa T. Appropriate therapy and characteristics of reflux esophagitis in elderly patients (in Japanese). J Geriatr Gastroenterol. 1994;6:107–12.

Tada N, Nagai T, Shintani E, Miyairi Y. A clinical study on reflux esophagitis in the aged. Tama Symp J Gastroenterol. 1991;5:54–8.

Kusano M, Kouzu T, Kono T, Ohara S. The prevalence of hiatus hernia in the Japanese (in Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc. 2005;47:962.

Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Moriyama S, Nakayama Y, Kinpara T, et al. Gastric mucosal atrophy and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in reflux esophagitis of the elderly (in Japanese). Nippon Shoukakibyou Gakkaishi. 1996;93:235–9.

Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Kuwabara M, Nagano M, Okamoto T, Tanaka M. High incidence of newly-developed gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese community: a 6-year follow-up study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:393–7.

Azumi T, Adachi K, Arima N, Tanaka S, Yagi J, Koshino K, et al. Five-year follow-up study of patients with reflux symptoms and reflux esophagitis in annual medical check-up field. Intern Med. 2008;47:691–6.

Kawanishi M. Will symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease develop into reflux esophagitis? J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:440–3.

Manabe N, Yoshihara M, Sasaki A, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Chayama K. Clinical characteristics and natural history of patients with low-grade reflux esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:949–54.

Yoshida T, Sakaki N, Aonuma K, Ogino M, Mon Y, Shinkai Y, et al. Gastric mucosa in patients with reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc. 1981;23:775–80.

Takaaki J, Furuya S, Takamasu M, Atsumi M, Ebisui S, Fukumitsu S, et al. Endoscopic study of reflux esophagitis with reference to the course of endoscopical findings (in Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc. 1990;32:1097–103.

Nakajima S, Hattori T. Active and inactive gastroesophageal reflux diseases related to Helicobacter pylori therapy. Helicobacter. 2003;8:279–93.

Hamada H, Haruma K, Mihara M, Kamada T, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, et al. High incidence of reflux oesophagitis after eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori: impacts of hiatal hernia and corpus gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:729–35.

Murai T, Miwa H, Ohkura R, Iwazaki R, Nagahara A, Sato K, et al. The incidence of reflux oesophagitis after cure of Helicobacter pylori in a Japanese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(suppl 1):161–5.

Yachida S, Saito D, Kozu T, Gotoda T, Inui T, Fujishiro M, et al. Endoscopically demonstrable esophageal changes after Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with gastric disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1346–52.

Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Kato K, Toyota T, et al. Increased gastric acid secretion after Helicobacter pylori eradication may be a factor for developing reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:813–20.

Fukuchi T, Ashida K, Yamashita H, Kiyota N, Tsukamoto R, Takahashi H, et al. Influence of cure of Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric acidity and gastroesophageal reflux: study by 24-h pH monitoring in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:350–60.

Inoue H, Imoto I, Taguchi Y, Kuroda M, Nakamura M, Horiki N, et al. Reflux esophagitis after eradication of Helicobacter pylori is associated with the degree of hiatal hernia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1061–5.

Yamamori K, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japanese patients with peptic ulcer disease after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 1):107–11.

Sasaki A, Haruma K, Manabe N, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Long-term observation of reflux oesophagitis developing after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1529–34.

Miwa H, Sugiyama Y, Ohkusa T, Kurosawa A, Hojo M, Yokoyama T, et al. Improvement of reflux symptoms 3 years after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection: a case-controlled study in the Japanese population. Helicobacter. 2002;7:219–24.

Ishiki K, Mizuno M, Take S, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yamamoto K, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication improves pre-existing reflux esophagitis in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:474–9.

Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Abe Y, Kato K, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents erosive reflux oesophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Gut. 2001;49:330–4.

Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20.

Kirizuka K, Nishizaki H, Yamamoto K, Ueshima M, Ohya M, Moridera K, et al. Correlation between GERD and DM patients (in Japanese). Kobe City Hosp Bull. 2003;42:39–42.

Nishida T, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Arimitsu S, Sato T, Haruna Y, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease related to diabetes: analysis of 241 cases with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:258–65.

Akiyama T, Tomisu C, Gouhara S, Miyajima Y, Arikawa M, Tashiro M, et al. The prevalence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in diabetic patients based on QUEST score (in Japanese). Dig Absorpt. 2004;27:46–9.

Hisano N, Kojima Y, Kanno R, Ono M, Yoshitsugu M, Hiyoshi T. Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with diabetes mellitus using questionnaire (in Japanese). Naika. 2006;98:927–9.

Kase H, Hattori Y, Sato N, Banba N, Kasai K. Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in diabetes patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;79:e6–7.

Ariizumi K, Koike T, Ohara S, Inomata Y, Abe Y, Iijima K, et al. Incidence of reflux esophagitis and H. pylori infection in diabetic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3212–7.

Kinekawa F, Kubo F, Matsuda K, Fujita Y, Tomita T, Uchida Y, et al. Relationship between esophageal dysfunction and neuropathy in diabetic patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2026–32.

Kinekawa F, Kubo F, Matsuda K, Kobayashi M, Furuta Y, Fujita Y, et al. Esophageal function worsens with long duration of diabetes. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:338–44.

Kinekawa F, Kubo F, Matsuda K, Kobayashi M, Furuta Y, Yamanouchi H, et al. Is the questionnaire for the assessment of gastroesophageal reflux useful for diabetic patients? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1017–20.

Akatsu T, Yoshida M, Kawachi S, Tanabe M, Shimazu M, Kumai K, et al. Consequences of living-donor liver transplantation for upper gastrointestinal lesions: high incidence of reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2108–22.

Kakizaki S, Sohara N, Sato K, Nakajima Y, Tsunoda N, Takagi H, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in chronic liver disease using frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD (in Japanese). Jpn J Clin Exp Med. 2006;83:419–22.

Ueda A, Enjoji M, Kato M, Yamashita N, Horikawa Y, Tajiri H, et al. Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as a complication in patients with chronic liver diseases: estimation of frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD (in Japanese). Fukuoka Igakkaishi. 2007;98:373–8.

Abe H, Yoshizawa K, Kitahara T, Mitobe J, Hirohama K, Aizawa R, et al. Significance of the gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) screening with the frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD (FSSG) in patients with chronic liver disease (in Japanese). Shoukakika. 2007;44:421–5.

Suzuki K, Suzuki K, Koizumi K, Ichimura H, Oka S, Takada H, et al. Measurement of serum branched-chain amino acids to tyrosine ratio level is useful in a prediction of a change of serum albumin level in chronic liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:267–72.

Nishiguchi S, Shiomi S, Kurooka H, Iwata Y, Sasaki N, Tamori A, et al. Randomized trial assessing gastric emptying in patients with chronic hepatitis C during interferon-alpha or -beta therapy and effect of cisapride. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:73–8.

Okamoto E, Amano Y, Fukuhara H, Furuta K, Miyake T, Sato S, et al. Does gastroesophageal reflux have an influence on bleeding from esophageal varices? J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:803–8.

Suganuma N, Shigedo Y, Adachi H, Watanabe T, Kumano-Go T, Terashima K, et al. Association of gastroesophageal reflux disease with weight gain and apnea, and their disturbance on sleep. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;55:255–6.

Uchiyama Y, Hayashi M, Matsui K, Hirata M, Fujita S, Konishi Y, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (in Japanese). Bull Fujita-Gakuen Med Soc. 2003;27:73–7.

Sugai N, Suzuki J. Sleep apnea syndrome and reflux esophagitis (in Japanese). JOHNS. 2006;22:819–22.

Sato H, Iwashima A, Kawabe S, Nakayama H, Yoshizawa H, Gejyo F, et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on gastroesophageal reflux in sleep apnea syndrome (in Japanese). Nippon Kokyu Kanri Gakkaishi. 2005;14:491–5.

Tanimura H, Imaizumi N, Watabe Y, Imamura E, Sugimoto K, Miki T, et al. Study of gastroesophageal reflux disease with sleep apnea syndrome (in Japanese). Ther Res. 2005;26:892–4.

Tanaka H, Minoshima Y, Umezono K, Ito S, Kobayashi S, Nishio H. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome by using frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD (in Japanese). Med Postgrad. 2007;45:140–4.

Sato H, Iwashima A, Nakayama H, Gejyo F, Hasegawa T, Suzuki E. Diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease associated with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome using the frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD and therapeutic effects of continuous positive airway pressure and rabeprazole (in Japanese). J New Rem Clin. 2008;57:1107–13.

Mizuta Y, Takashima F, Shikuwa S, Ikeda S, Kohno S. Is there a specific linkage between obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and gastroesophageal reflux disease? Dig Endosc. 2006;18:88–97.

Suzuki J, Sasaki K, Adachi T, Sadaoka K, Kanai T, Seki H, et al. A study of gastroesophageal reflux by 24-h esophageal pH monitoring in patients with bronchial asthma (in Japanese). Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;94:519–25.

Tomioka H, Itani T, Nakase H, Sakamoto H, Fujiyama R, Ohnishi H, et al. Bronchial asthma and reflux esophagitis. A clinical study on 106 cases with bronchial asthma (in Japanese). Jpn J Chest Dis. 1999;58:829–35.

Nakase H, Itani T, Mimura J, Kawasaki T, Komori H, Tomioka H, et al. Relationship between asthma and gastro-oesophageal reflux: significance of endoscopic grade of reflux oesophagitis in adult asthmatics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:715–22.

Tsugeno H, Mizuno M, Fujiki S, Okada H, Okamoto M, Hosaki Y, et al. A proton-pump inhibitor, rabeprazole, improves ventilatory function in patients with asthma associated with gastroesophageal reflux. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:456–61.

Shimizu Y, Dobashi K, Kobayashi S, Ohki I, Tokushima M, Kusano M, et al. High prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease with minimal mucosal change in asthmatic patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;209:329–36.

Shimizu Y, Dobashi K, Kobayashi S, Ohki I, Tokushima M, Kusano M, et al. A proton pump inhibitor, lansoprazole, ameliorates asthma symptoms in asthmatic patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;209:181–9.

Sato A, Tanifuji Y, Kobayashi H, Inoue H. Effects of proton pump inhibitor on airway hyperresponsiveness in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux (in Japanese). Arerugi. 2006;55:641–6.

Nogami H, Kamikawaji N, Shimoda T, Shoji S, Nishima S. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease as a complication in asthmatics (in Japanese). Jpn J Chest Dis. 2007;66:684–9.

Takezawa T. The relationship between bronchial asthma and gastroesophageal reflux disease (in Japanese). Teikyo Med J. 2008;31:75–86.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture in Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fujiwara, Y., Arakawa, T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol 44, 518–534 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-009-0047-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-009-0047-5