Abstract

Crystalline exotic boulders within the sedimentary sequences of the Outer Carpathians likely represent Proto-Carpathian basement, which was exposed and eroded during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic evolution of the Western Carpathian basin. The majority of the boulders were derived from the Silesian Ridge, which separated the Magura Basin and the Silesian Domains, and which became a source region during Late Cretaceous–Early Paleocene tectonism. Felsic crystalline clasts within the Silesian Nappe yield U–Pb zircon magmatic protolith ages of 603.7 ± 3.8 Ma and 617.5 ± 5.2 Ma while felsic crystalline clasts within the Subsilesian Nappe yield an age of 565.9 ± 3.1 Ma and thus represent different magmatic cycles. The U–Pb zircon data also imply that the Silesian Ridge was a fragment of the eastern part of the Brunovistulia microcontinent. The presence of inherited zircon cores, dated at 1.3 and 1.7 Ga, suggests a Baltican source for the clasts, as opposed to Gondwana. We infer that Late Neoproterozoic felsic magmatism within the Proto-Carpathian continent represents a long-living magmatic arc, which formed during prolonged Timmanian/Baikalian rather than Pan-African/Cadomian orogenesis. Mafic exotic blocks, found within the Magura Nappe, yield U–Pb zircon ages of 613.3 ± 2.6 Ma and 614.6 ± 2.5 Ma and likely represent a fragment of an obducted ophiolitic sequence. The protolith of these mafic boulders could represent Paleoasian Ocean floor located to the east of Cadomia, obducted during later orogenic processes and incorporated into the accretionary prism. All analysed exotic clasts show no evidence for younger (Variscan) reworking, which is characteristic of both western Brunovistulia and the Central Western Carpathians and the Cadomian elements of Western Europe. The Silesian and Subsilesian basins thus had a likely source area in the eastern part of Brunovistulia, while the source of the Magura Basin was the Fore-Magura Ridge, whose basement potentially represents an accretionary prism on the margin of the East European Craton.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Carpathians are a mountain belt of Alpine age, located in the central part of the Alpine chain of Europe, stretching c. 1300 km from Austria through the Czech Republic to Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine and Romania. Geographically the arc is divided into the Western, Eastern and Southern Carpathians (Fig. 1a). Traditionally, the Western Carpathians are subdivided into the Central Carpathians and the Outer Carpathians, separated by the Pieniny Klippen Belt (Plašienka et al. 1997; Gawęda and Golonka 2011). In the Central Carpathians the pre-Alpine basement crops out in the core of the mountain belt, while the Outer Carpathians are built of the nappes and thrust sheets of Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks thrust over the European Platform (Figs. 1a, b, 2). These sediments were believed to have been deposited on crystalline basement, termed the Proto-Carpathians, which presumably underlain the Mesozoic and Cenozoic basins of the Carpathian orogenic system (Żelaźniewicz et al. 2002; Linnemann et al. 2008, Golonka et al. 2011) and which supplied significant detritus to the western part of the Tethys Realm during the Mesozoic. This Late Precambrian–Paleozoic basement probably formed during separate tectonic phases (e.g. Poprawa et al. 2006; Budzyń et al. 2011), but its geological history and affinity to known geological massifs of similar age are not clear. The Proto-Carpathian basement is covered by several kilometers of Jurassic–Miocene sediments (predominantly marine clastics) of the Carpathian basins. During the Cretaceous–Neogene Alpine orogenesis, the Carpathian segment of the Tethys margin was divided into a series of smaller basins, separated by ridges or highs (Fig. 3), prior to incorporation into a series of nappe stacks and thrust sheets, which now form the Outer Carpathians and which were thrust over the European Platform (Fig. 1b; e.g. Oszczypko 2006; Golonka and Waśkowska-Oliwa 2007; Golonka et al. 2011 and references therein).

Modified from Starzec et al. (2017)

A simplified geological sketch of the Carpathian Chain within the Europe with the location of the study area in the Outer Western Carpathians (a) and the geological map of the Polish Outer Carpathians with the locations of the sampling points (b).

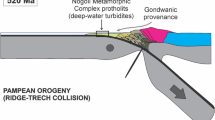

Paleogeography of the Outer Carpathian basins during the Late Cretaceous–Paleocene with palinspastic cross-section showing the Outer Carpathian basins during Paleocene (after Golonka et al. 2011). SK Skole Basin, SSR Subsilesian Ridge, SB Silesian basin, SR Silesian Ridge, FMB Fore-Magura Basin, FMR Fore-Magura Ridge, MGB Magura Basin

During sedimentary infill of the Carpathian basins, coarse clasts (with large blocks up to several meters in size) were derived from the basins margins and intrabasinal ridges. These predominantly crystalline clasts were transported by turbidity currents and debris flows, forming conglomerates and olistostromes. The crystalline exotics are represented by magmatic (predominantly plutonic) and metamorphic rocks (e.g. Wieser 1952; Unrug 1968; Oszczypko and Salata 2005). These exotic blocks within the flysch sequences of the Outer Carpathians are the only remnants of the Proto-Carpathian basement and are poorly characterized and understood; the majority is being derived from the Silesian Ridge (Budzyń et al. 2011; Burda et al. 2019).

The main goal of this paper is to reconstruct the paleotectonic evolution of the Proto-Carpathian basement rocks by undertaking provenance analysis on exotic clasts from within three different nappes (the Subsilesian Nappe, the Silesian Nappe and the Magura Nappe) using petrological and geochronological data. These data are used to test linkages of the Proto-Carpathian basement with the Central European pre-Alpine basement, with implications for the development of the southern margin of Baltica in the Precambrian to Early Paleozoic and their role in Alpine orogenesis.

Geological setting and sampling

The Outer Western Carpathians (Fig. 1a, b) are comprised of a stack of nappes and thrust sheets containing up to 6 km of Upper Jurassic–Miocene continuous flysch sequences, which were thrust over the European Platform and autochthonous Miocene cover of the Carpathian Foredeep. The nappe sequences in the Outer Western Carpathian were detached from their basement (Golonka et al. 2005; Ślączka et al. 2006) and are comprised of the Magura Nappe, Fore-Magura Nappe Group, Silesian Nappe, Subsilesian Nappe and Skole (Skiba) Nappe (Fig. 1b).

The Magura Nappe represents the structurally highest, southernmost unit. It was thrust over the Fore-Magura Nappe Group and the Silesian Nappe. The Silesian Nappe, which includes a near continuous Upper Jurassic–Lower Miocene succession, occupies the central part of the Outer Carpathians. In the western sector of the Polish Outer Carpathians the thickness of the Silesian Nappe sedimentary rocks is estimated at about 4500 m. The Subsilesian Nappe includes Cretaceous–Neogene sediments deposited on an inferred Subsilesian Ridge that separated the Silesian and Skole basins (Fig. 3). The crystalline boulders analysed in this study were collected from the Subsilesian, Silesian and Magura nappes (Fig. 2b).

Nowe Rybie exotic (Subsilesian Nappe)

This granodiorite boulder was collected from the right tributary of the Pluskawka Stream near the villages of Nowe Rybie and Kamionna in the Beskid Wyspowy Range (Fig. 1b, Grid reference: N49°47′26.7″, E20°21′34.4″). This large block (110 cm in diameter) was sampled from a mélange complex of the Upper Cretaceous variegated marls, gray marls and sandstones (Frydek and Węglówka formations) exposed in a Subsilesian tectonic widow within the Silesian Nappe (Skoczylas-Ciszewska 1956).

Istebna exotics

Several gneissic clasts from the Upper Cretaceous–Paleocene Czarna Wisełka Member (the Upper Istebna Beds; the Istebna Formation, the Silesian Nappe) were collected at Istebna village in the Beskid Śląski Range (Fig. 1b; Grid Reference: N49°34′39.5″, E18°58′12.5″). They occurred within a 4-m-thick conglomerate layer with normal- and reverse-graded portions. The level containing the exotic boulders is located 1.3 m above the base of the conglomerate layer. The exotic blocks are up to 0.7–1.6 m in diameter and are poorly rounded (Starzec et al. 2017).

Osielec exotics (Magura Nappe)

Several metadiorite–metagabbro boulders, up to 50 cm in size, were collected from the Osielczyk Stream, in the southeastern part of the village of Osielec village in the Beskid Makowski Range (Grid reference: N49°41′09.4″, E19°46′22.0″). These exotic clasts were found within Eocene olistostromes (Wieser 1952; Cieszkowski et al. 2017) of the Pasierbiec Member of the Beloveza Formation (part of the Rača Unit of the Magura Nappe; Cieszkowski et al. 2017; Golonka and Waśkowska 2012 and references therein; Fig. 1b). The crystalline gabbroic clasts range from 0.2 to 3.5 m in size and are poorly rounded and have a sandy-conglomeratic or sandy-mudstone matrix.

Analytical techniques

Microscopy

Petrographic analyses of thin sections were undertaken at the Faculty of Earth Sciences in the University of Silesia using an Olympus BX-51 microscope to constrain textural and microstructural relationships and to determine the presence of zircon. The petrographical observations were used to select representative samples for subsequent electron probe micro-analysis and whole-rock geochemical analyses.

Electron probe micro-analyses (EPMA)

Microprobe analyses of the main rock-forming and accessory minerals were carried out at the Inter-Institutional Laboratory of Microanalyses of Minerals and Synthetic Substances, Warsaw, using a CAMECA SX-100 electron microprobe. The analytical conditions employed an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, a beam current of 20 nA, counting times of 4 s for peak and background and a beam diameter of 1–5 μm. Reference materials, analytical lines, diffracting crystals, mean detection limits (in wt%) and uncertainties were as follows: rutile—Ti (Kα, PET, 0.03, 0.05), diopside—Mg (Kα, TAP, 0.02, 0.11), Si—(Kα, TAP, 0.02, 0.21), Ca—(Kα, PET, 0.03, 0.16), orthoclase—Al (Kα, TAP, 0.02, 0.08), and K (Kα, PET, 0.03, 0.02), albite—Na (Kα, TAP, 0.01, 0.08), hematite—Fe (Kα, LIF, 0.09, 0.47), rodonite—Mn (Kα, LIF, 0.03, 0.10), phlogophite—F (Kα, TAP, 0.04, 0.32), tugtupite—Cl (Kα, PET, 0.02, 0.04), Cr2O3—Cr (Kα, PET, 0.04, 0.01), ZirconED2—Zr (Lα, PET, 0.01, 0.01), Nb2O3-MAC—Nb (Lα, PET, 0.09, 0.01), V2O5—V (Kα, LIF, 0.02, 0.01), YPO4—Y (Lα, TAP, 0.05, 0.05), CeP5O14—Ce (Lα, LPET, 0.09, 0.02), NdGaO3—Nd (Lβ, LIF, 0.31, 0.24), ThO2—Th (Mα, LPET, 0.09, 0.09), UO2—U (Mα, LPET, 0.16, 0.13).

Whole-rock analyses

Whole-rock analyses were undertaken by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for major and large ion lithophile trace elements (LILE), and by fusion and ICP–MS for high field strength elements (HFSE) and rare earth elements (REE) at Bureau Veritas Minerals (Canada). Preparation involved lithium borate fusion and dilute digestions for XRF and lithium borate decomposition or aqua regia digestion for ICP–MS. LOI was determined at 1000 °C. Uncertainties for most of major elements are 0.01%, except for SiO2 which is 0.1%. REE were normalized to C1 chondrite (McDonough and Sun 1995).

Mineral separation and imaging

Zircon crystals were separated using standard techniques (crushing, hydro-fracturing, washing, Wilfley shaking table, Frantz magnetic separator and hand picking). Mineral separation was carried out at the Institute of Geological Sciences at the Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków, Poland. The crystals were cast in 25 mm diameter epoxy resin mounts, ground and polished to half-thickness to expose the grain interiors. Internal mineral textures were then characterized by back-scattered electron (BSE) and cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging, using a FET Philips 30 scanning electron microscope with a 15 kV accelerating voltage and a beam current of 1 nA at the Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Silesia, Sosnowiec, Poland.

LA–ICP–MS U–Pb zircon dating

LA–ICPMS U–Pb age data were acquired using a Photon Machines Analyte Excite 193 nm ArF excimer laser-ablation system with a HelEx 2-volume ablation cell coupled to an Agilent 7900 ICPMS at the Department of Geology, Trinity College Dublin. The instruments were tuned using NIST612 standard glass to yield Th/U ratios of unity and low oxide production rates (ThO+/Th+ typically < 0.15%). A repetition rate of 12 Hz and a circular spot of 24 μm were employed. A quantity of 0.4 l min−1 He carrier gas was fed into the laser cell, and the aerosol was subsequently mixed with 0.6 l min−1 Ar make-up gas and 11 ml min−1 N2. Eight isotopes (90Zr, 202Hg, 204Pb, 206Pb, 207Pb, 208Pb, 232Th and 238U) were acquired during each analysis, which comprised 25 s of ablation and 12 second washout, the latter portions of which were used for the baseline measurement. Data reduction of the raw U–Pb isotope data was performed through the “VizualAge” data reduction scheme (Petrus and Kamber 2012) in the freeware IOLITE package (Paton et al. 2011). Sample-standard bracketing was applied after the correction of downhole fractionation to account for long-term drift in isotopic or elemental ratios by normalizing all ratios to those of the U–Pb reference standards. Final age calculations were made using the Isoplot add-in for Excel (Ludwig 2012). 91500 zircon (206Pb/238U TIMS age of 1065.4 ± 0.6 Ma; Wiedenbeck et al. 1995) was used as the primary U–Pb calibration standard. The secondary standards AusZ2 zircon (206Pb/238U TIMS age of 38.8963 ± 0.0044; Kennedy et al. 2014), Plešovice zircon (206Pb/238U TIMS age of 337.13 ± 0.37 Ma; Sláma et al. 2008) and WRS 1348 zircon (206Pb/238U TIMS age of 526.26 ± 0.70; Pointon et al. 2012) yielded LA–ICPMS concordia ages of 39.07 ± 0.44 Ma, 340.5 ± 1.5 Ma and 525.4 ± 2.3 Ma, respectively.

Results

Petrography and mineral chemistry

Nowe Rybie granite

This equigranular biotite granite (sample GN-PL; Fig. 4a) is composed of plagioclase (An30–21), zoned perthitic K-feldspar (Or91–78Ab18–4Cn0–2 with a mean perthite composition of Ab84Or15An1), quartz, biotite (Ti = 0.37–0.42 a.p.f.u.; #mg = 0.35–0.38; Table 1) and magmatic muscovite (Ti = 0.10–0.15 a.p.f.u., #mg = 0.45–0.53; Table 1). Accessories are Mn-bearing ilmenite (Fe1.0–0.87Mn0.95–0.80Ti1.0–0.88O3; Table 2), fluorapatite, zircon and rutile. Calculated ternary feldspar temperatures imply cooling from late magmatic conditions at 650–550 °C pointing to early perthite exsolution (Table 3).

Microphotographs showing mineral composition and rock microtextures. a Nowe Rybie weakly deformed granodiorite; b strongly deformed orthogneiss from Istebna; c porphyroblast of poikilitic K-feldspar from istebna; d non-foliated metagabbroic rock from Osielec; e foliated strongly altered metagabbroic/metadioritic rock from Osielec. Qtz quartz, Kfs K-feldspar, Pl plagioclase, Bt biotite, Amph amphibole, Chl chlorite, Ep epidote

Istebna exotics

The exotic blocks from the Istebna Formation are felsic augen gneisses, which show a strong foliation and S-C fabrics, highlighted by quartz ribbons (Fig. 4b). They are developed as medium-grained (sample IST-C) and coarse-grained (sample IST-J) varieties.

The porphyroblasts comprise unzoned perthitic K-feldspars (Or89–99Ab4–11Cn0–1; Fig. 4c), with quartz inclusions. The matrix is composed of quartz, K-feldspar (Or93–96Ab3–6Cn1–2), plagioclase (An25–28Ab71–73Or1–2), muscovite with phengitic substitution (MgVI + SiIV = AlVI + AlIV; Si = 6.3–6.4 a.p.f.u.), locally forming ribbons (Table 1) and biotite (Ti = 0.25–0.35 a.p.f.u.; #mg = 0.28–0.34; Table 1). Accessories are fluorapatite, zircon and monazite-(Ce). Metamorphic conditions were estimated using Ti-in-biotite geothermometry (Henry et al. 2005) and phengite geobarometry (Massone and Schreyer 1987) and yield P–T conditions of 600–660 °C and 400–500 MPa.

Osielec mafic exotics

The mafic exotics are metadioritic–metagabbroic in composition, with both non-foliated (sample OSC) and foliated (samples D3, D6, D6-2; Fig. 4d, e) clasts. Amphibole (Mg-hornblende and ferro-magnesian hornblende, Fig. 4d; Table 4), plagioclase (An39–51Ab57–46Or2–3) and magnetite–ilmenite–rutile exsolution after spinel (Table 2) are the rock-forming minerals. The accessories are fluorapatite, present as idiomorphic crystals (Fig. 4d) and zircon, forming inclusions in the rock-forming phases. Two secondary mineral assemblages represent two different stages of secondary overprinting. Assemblage 1 is characterized by actinolitic hornblende–actinolite (Table 4), epidote (Table 5), biotite (Ti = 0.64–0.75 a.p.f.u.; #mg = 0.42–0.54; Table 1), titanite (Table 5), albite–oligoclase, chlorite (Chl1) and rutile (Table 2). Epidote and titanite usually form pseudomorphs after pyroxene (Fig. 5a, b). Assemblage 2 is comprised of ribbons of chlorite (Chl2)–quartz–epidote–sericite defining a metamorphic foliation (Fig. 4e). Chlorite in the OSC and D6 samples contains 53–86% of the clinochlore (Mg5Al)(Si3Al)O10(OH) end-member, 10–51% of the chamosite (Fe2+5Al)(Si3Al)O10(OH) end-member and < 2% of the pennite (Mn5Al)(Si3Al)O10(OH) end-member (classification after Bailey 1980; Table 6).

The magmatic amphibole chemistry yields crystallization pressures of 280–250 MPa at temperatures of 730–780 °C (Schmidt 1992; Holland and Blundy 1994). Chlorite thermometry (sample D6) using the Cathelineau and Nieva (1985) and Jowett (1991) methodologies yielded temperature ranges of 315–335 °C (Chl1 formation stage) and 290–305 °C (ribbon Chl2 chlorite). Chlorite in the non-foliated OSC sample yielded temperatures of 310–325 °C (Table 6).

Whole-rock geochemistry

The peraluminous calc-alkaline Nowe Rybie granite (Fig. 6a, b) has a SiO2 content of 70.90 wt %, with ASI = 1.28 and #mg = 0.56. It has a low total REE content with flat chondrite-normalized REE patterns (Eu/Eu* = 1.04, CeN/YbN = 10.93; Table 7; Fig. 7a), a high Rb/Sr ratio of 0.78 and a ThN/UN ratio of 1.73, suggest a weakly fractionated and weakly oxidized (crustal) source melt. The zircon saturation temperature calculated on the basis of the whole-rock Zr content (Watson and Harrison 1983) is 781 °C (Table 7).

Classification position of the Outer Carpathians exotic rocks in: a alkali (K2O + Na2O) versus SiO2 TAS classification diagram after Middlemost (1985); b K2O versus SiO2 classification diagram after Peccerillo and Taylor (1976); c Nb/Y versus Zr/Y for Osielec metagabbroic/metadioritic rocks, with line separating enriched from depleted sources after Fitton (2007)

Normalization values after McDonough and Sun (1995)

Chondrite (C1) normalized REE patterns (a) and primitive-mantle normalized (b) multi-element patterns of the analysed exotic blocks from the Outer Carpathians.

The felsic Istebna orthogneisses are high SiO2 (72.71 and 73.27 wt%; Table 7) and peraluminous (ASI = 1.19–1.21), with similar #mg numbers (0.39 and 0.45) and major and trace elements characteristics (high-K—calc-alkaline protoliths; Fig. 6a, b). They differ slightly in Rb/Sr and Nd/Th ratios, Th and U concentrations and REE patterns (Eu/Eu* = 0.50 and 0.84; CeN/YbN = 35.3 and 29.56; Table 7; Fig. 6a, b). The primitive-mantle-normalized multi-element diagram (Fig. 6b) points to an arc-setting, with characteristic negative Nb and Ta anomalies. Zircon saturation temperatures calculated on the basis of the whole-rock Zr content yield temperatures of 777–760 °C (Table 7).

The mafic Osielec exotic clasts show similar major element characteristics, with SiO2 contents of 57.58–60.30 wt% (Fig. 6a), metaluminous ASI values (1.03–0.84), low Rb/Sr ratios (0.12–0.04), relatively flat REE patterns (Eu/Eu* = 0.81 – 0.94; CeN/YbN = 4.75–5.52; Table 7; Fig. 7a) and ThN/UN ratios of 0.56–1.01, implying a non-fractionated moderately oxidized (lower crustal) source melt.

Zircon petrology and U–Pb data

Nowe Rybie granite

Zircon crystals from sample GN-PL are euhedral to subhedral, and long-prismatic to acicular (aspect ratios from 3:1 to 10:1). Cathodoluminescence imaging reveals the presence of magmatic oscillatory zoning, local sector zoning, with local truncations near inclusions (Fig. 8a). No xenocrystic cores were noted. 14 grains yield a concordia age of 565.9 ± 3.1 Ma (MSWD = 3.1, probability of concordance 0.076; Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 9a).

Concordia plots of LA–ICP–MS zircon analytical results from Nowe Rybie granite (a), and medium-grained Istebna orthogneiss with inherited cores (b) and magmatic rims (c); strongly deformed Istebna coarse-grained orthogneiss (d); undeformed Osielec metagabbro (e), strongly deformed Osielec metagabbro (f)

Istebna exotic blocks

Zircon crystals from two samples (IST-C and IST-J) were analysed. In both cases the zircon crystals are euhedral and prismatic with aspect ratios of 2:1–4:1. Acicular crystals were sporadically observed. CL imaging reveals the presence of oscillatory magmatic zoning and rare xenocrystic cores (Fig. 8b). For sample IST-C, 8 dates on 6 grains were obtained. Two xenocrystic cores yield concordia ages of c. 1770 ± 17 Ma and 1319.8 ± 19.7 Ma (Fig. 9b; Supplementary Table 1), while the oscillatory rims yielded a 617.5 ± 5.2 Ma lower intercept age (MSWD = 0.24, probability of fit = 0.92; Fig. 9c; Supplementary Table 1). Five oscillatory rim analyses in sample IST-J yielded a concordia age of 603.7 ± 3.8 Ma age (MSWD = 1.6, probability of concordance = 0.21; Fig. 9d; Supplementary Table 1).

Osielec exotic blocks

Two samples were separated for zircon analyses, comprising both a non-foliated, homogeneous sample with preserved magmatic fabrics (sample OSC) and a sample with a pervasive metamorphic foliation and overprint (sample D6). The zircon crystals in both samples do not differ in size, shape or internal CL features. They are colourless or slightly pink, euhedral, isometric to prismatic (aspect ratios 1:1–4:1). The zircon crystals vary in length from ca. 100 to 250 μm. The CL images reveal igneous oscillatory zoning, with growth bands varying between fine and broad (up to 20 µm) within individual grains and local sector zoning is visible (Fig. 8c). The CL intensity is variable, but mostly moderate to weak. Xenocrystic cores are lacking.

For the OSC sample, 25 dates on 25 crystals were obtained (Supplementary Table 1), yielding a concordia age of 613.3 ± 2.6 Ma (Fig. 9e; MSWD = 3.3, probability of concordance = 0.069). For sample D6, 36 dates on 36 grains were obtained. Three analyses were discordant, while the rest yield a concordia age of 614.6 ± 2.5 Ma (Fig. 9f; MSWD = 0.90, probability of concordance = 0.34; Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Petrological interpretation of the exotic blocks

Felsic exotic clasts

In the Istebna orthogneisses (samples IST-C and IST-J), the igneous oscillatory zonation of the zircon crystals together with the whole-rock geochemistry implies a granitoid protolith. The granitoid protolith, with highly fractionated REE patterns (Fig. 7a) and a high-K-calc-alkaline chemistry, could be associated with an arc-related tectonic setting (Fig. 7b). No new growth of metamorphic zircon was observed. The magmatic ages c. 618 and c. 604 Ma do not overlap within analytical uncertainty and imply two different pulses of magmatic activity (Fig. 9b, c). The younger event overlaps in age with published data from the Kobylec granitic pebbles in the Silesian Nappe, while the older age is similar in age to the Lusina gneiss from the same structural unit (Budzyń et al. 2011). Inherited zircon core ages of c. 1320 Ma and c. 1770 Ma (Fig. 9b) are similar in age to Mesoproterozoic ages from gneissic/metagranitoid exotic blocks and zircon xenocrystic core ages from the eastern part of the Silesian Nappe (Michalik et al. 2006), to zircon xenocrystic core ages from the Brunovistulian basement in the Svratka Dome in the Czech Republic (Soejono et al. 2017).

The peraluminous, weakly fractionated Nowe Rybie granite shows a calc-alkaline character in contrast to the high-K calc-alkaline Istebna orthogneisses (Fig. 6b; Table 7a). The morphology of the zircon crystals with high aspect ratios and the lack of any metamorphic overprint suggest that the U–Pb zircon age of c. 566 Ma represents the crystallization of the granitic protolith, which represents a separate magmatic event not genetically related to the Istebna orthogneisses.

Mafic exotics—Osielec metagabbro–metadiorite

The undeformed rock fabric, whole-rock geochemistry and zircon internal zonation all imply a magmatic character for the protolith. The primary gabbroic–dioritic mineral assemblage shows relatively weak REE fractionation, no Eu anomalies as well as low Nb/Y ratios, which could suggest a mid-ocean ridge (MOR) character (Figs. 6c, 7a; Table 7). On the other hand, the Nb- and Ta-negative anomalies could suggest an arc-related setting (Fig. 7b), but might also result from crustal contamination, which is supported by negative-Ti and positive-Th anomalies (Fig. 7b). The two dated samples yield similar ages of c. 615 Ma, which are interpreted as the age of magmatic crystallization of the MOR-related gabbroic protolith.

Paleotectonic interpretation

Precambrian paleotectonic interpretation

Fragments of basement of supposed Cadomian–Pan-African affinity are found in the western, central European Variscan belt from Iberia through Armorica (NW France), Erzgebirge (Saxoturingian zone, Germany), Bohemian Massif, Brunovistulia and Małopolska massif (Czechia and southern Poland), as crystalline massifs within the Carpathian Alps and extending to the Transcaucasus region in easternmost Europe (e.g. Chantraine et al. 2001; Linneman et al. 2014 and references therein). These Late Neoproterozoic basement terranes formed a result of the assembly of the Pannotia supercontinent (Dalziel et al. 1994; Golonka et al. 2006 and references therein) and the majority of them exhibit Variscan reworking (e.g. Soejono et al. 2017).

The Brunovistulia terrane is interpreted as a microcontinental fragment that docked onto Gondwana during the Cadomian Orogeny (Dudek 1980; Linnemann et al. 2008). It is located on the eastern flank of the Bohemian Massif, is covered by Ediacaran and Paleozoic deposits to the N and NE and overthrust by the Outer Carpathian flysch in the SE. The Vienna-Nowy Sącz gravity low is assumed to form the southern border of the Brunovistulia Terrane under the Carpathians cover (Kalvoda et al. 2008; Fig. 2). Brunovistulia has been divided into the Thaya and Slavkov terranes by a N–S trending ophiolite belt (725 ± 15 Ma; Finger et al., 1999), which were intruded by granitoids, representing prolonged (568–634 Ma) subduction-related magmatism (Soejono et al. 2017 and references therein). Brunovistulian orthogneisses are characterized by collision-related granitoid protoliths dated at 612.7 ± 1.0 Ma, 601 ± 3 and 634 ± 6 (Kröner et al. 2000, Linnemann et al. 2008; Soejono et al. 2017), while paragneisses have yielded metamorphic monazite total Pb ages of 608 ± 28 Ma, 577 ± 19 Ma and 549 ± 19 Ma (Finger et al. 1999). Granitoids from boreholes which penetrate the basement in the Upper Silesia Coal Basin below the Outer Carpathian overthrust, yield similar U–Pb zircon ages (573 ± 3 Ma from the Kęty-8 borehole, 544 ± 4 Ma from the Roczyny-3 borehole; Żelaźniewicz et al. 2002; Linnemann et al. 2008).

The magmatic ages of c. 617 and c. 604 Ma from the felsic exotic blocks in this study, imply that the Silesian Ridge could represent a fragment of Brunovistulia (Fig. 1). Earlier studies of exotic clasts from the Silesian Nappe also yielded similar ages (610 ± 6 Ma; 604 ± 6 Ma and 599 ± 6 Ma; Budzyń et al. 2011; 580 ± 6 Ma and 542 ± 21 Ma; Burda et al. 2019) potentially also implying a linkage between the Silesian Ridge and Brunovistulia. The granite from Nowe Rybie yields the youngest age in this study (565.5 ± 2.9 Ma) and overlaps in age with the youngest age population obtained from the basement of the Upper Silesia Coal basin and exotic clasts of inferred Brunovistulian provenance in the Outer Carpathians (Burda et al. 2019), Cadomian pebbles within glaciomarine deposits on the Bohemian massif (Linneman et al. 2018), as well as the Svratka Dome metagranite from Brunovistulia, which also shares a similar age and geochemistry (Soejono et al. 2017). These data support inferences that the Proto-Carpathian basement represents the eastern continuation of Brunovistulia.

Assuming the inverted position of Baltica inside Rodinia as suggested by Hartz and Torsvik (2002), the presence of magmatic activity older than 600 Ma could be attributed to the Timanian/Late Baikalian orogeny on the margins of Baltica and Siberia (Larionov et al. 2004; Fig. 10). These orogenic events overlap with Pan-African/Cadomian orogenesis along the Gondwana margin and can be traced along the present-day northern and northeastern borders of Baltica (e.g. Rehnström et al. 2002; Roberts and Siedlecka 2002). The magmatic events from c. 617 to c. 566 Ma may be related to the prolonged evolution of a magmatic arc on the margins of Baltica and Siberia, similar to that proposed by Linneman et al. (2014).

Plate tectonic map of Pannotia at 570 Ma (stereographic polar projection; modified from Golonka et al. 2006)

The presence of the inherited zircon cores of c. 1.3 and c. 1.7 Ga, in addition to formerly published data from the Outer Carpathians exotic blocks (c. 1.25–2.7 Ga; Michalik et al. 2006; c. 1.7–1.8 Ga and c. 2.1 Ga; Burda et al. 2019), which are consistent with a Svecofennian provenance, suggest Baltican affinity of the inherited zircon fraction (e.g. Wiszniewska et al. 2007 and references therein), without any typical Gondwanan signature.

The Osielec exotic block, the only mafic rock among the analysed samples and in previously published data, could represent a portion of the oceanic floor belonging to the Paleoasian Ocean (Gladkochub et al. 2013) or to a back-arc basin, developing on the margins of Baltica and Siberia. Paleoasian Ocean was inferred east of Cadomia, between the Bohemian Massif and Dobrogea (Fig. 10; Linnemann et al. 2008; Żelaźniewicz et al. 2009). The age of the magmatic protolith would represent oceanic spreading caused by the northward movement of Gondwana-derived terranes between Baltica, Siberia and Gondwana (Zonenshain et al. 1990; Dobretsov et al. 2003; Kuzmichev et al. 2005; Gladkochub et al. 2013).

The absence of any younger tectono-magmatic episodes (usually visible as Caledonian or Variscan zircon overgrowths), common in the western part of Brunovistulia (e.g. Finger et al. 1999), in the Cadomian/Pan-African massifs of Western Europe (Linneman et al. 2014), and the Cetic Massif in the Alps (Frasl and Finger 1988; Neubauer and Handler 2000) suggest that Pan-African/Cadomian/Timanian magmatic events were the only high-temperature events which affected these rocks and that eastern Brunovistulia was not involved in any younger tectono-thermal events. This supports the suggestion of Soejono et al. (2017) that Brunovistulia was already accreted to Baltica in the Cambrian and represented a passive margin during Paleozoic times in contrast to Cadomian terranes within the Variscan Belt of Europe.

The source areas for the exotic rocks in the Outer Carpathians during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic

The Mesozoic and Cenozoic paleogeography of the Outer Carpathians reflects a series of continental break-ups, rifts and collisions on the European platform (Golonka et al. 2005). For example, the Jurassic–Early Cretaceous Silesian Ridge originated as a result of these processes (Unrug 1968; Książkiewicz 1977), separating the Magura and Protosilesian Basin (Fig. 3). The opening of these basins is related to the propagation of the Atlantic rift system (Golonka et al. 2006) which affected the Central Carpathians realm during Cenomanian and Turonian times, forming several nappes with a northward sense of movement. At the same time the Central Carpathians were amalgamated with the Alps and the Pannonian terrane forming the ALCAPA plate. The northward movement of the ALCAPA plate caused the consumption of the major part of the Alpine Tethys Ocean and reorganization of the Outer Carpathian basins (Fig. 3). This tectonic reorganization produced both a series of ridges separating the Magura, Dukla-Fore-Magura, Silesian, and Skole basins, and large volumes of clastic material filling the basins. Late Cretaceous–Paleocene sedimentation in the Silesian Basin is represented mainly by thickly bedded, coarse-grained turbidites and fluxoturbidites of the Godula and Istebna formations (Unrug 1968; Ślączka et al. 2006), transported mainly from the Silesian Ridge (Fig. 3). The Istebna exotic clasts were sourced via debris flows from the crystalline basement of this ridge (Starzec et al. 2017). There are no age correlatives of the felsic exotic clasts in the Central Western Carpathians, where magmatic/metamorphic ages are all in the 370–340 Ma age range (e.g. Broska et al. 2013; Gawęda et al. 2016). This implies there was no link between the Central Carpathians and Outer Carpathian basins during the Cretaceous–Paleogene, and instead supports sediment transport directions from the Silesian and Subsilesian ridges, representing European Platform (Brunovistulia) basement rocks, to the Subsilesian and Silesian basins (Fig, 3). In the Magura Basin, sediment transport was likely derived from the Fore-Magura Ridge (Fig. 3; Bónová et al. 2018; Cieszkowski et al. 2017) of unknown basement affinity. The clasts of putative ocean floor remnants in the Magura Basin suggest that the Fore-Magura Ridge could contain fragments of an accretionary prism related to the consumption of the Paleoasian Ocean. If so the Fore-Magura Ridge could be comprised of post-Timanian/Cadomian magmatic and metamorphic rocks but this remains somewhat speculative and warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

U–Pb zircon and whole-rock geochemistry data from crystalline exotic blocks in the Outer Carpathian basin flysch imply that the eastern prolongation of the Brunovistulia terrane was a source area (i.e. representing Proto-Carpathian basement) during the Mesozoic and Early Cenozoic, and formed during multiple magmatic/metamorphic episodes from c. 618 to c. 566 Ma. This eastern part of Brunovistulia was not involved in any younger tectono-thermal events, in contrast to western Brunovistulia or crystalline blocks within the Alpine and Central Carpathians crystalline massifs, which were pervasively reworked during Variscan orogenesis. This suggests Brunovistulia was accreted to Baltica before the Cambrian and could represent a prolonged magmatic arc of Timannian/Pan-African/Cadomian age. Brunovistulia, representing a part of the North European Platform, formed the crystalline basement (Proto-Carpathian) for the sedimentary basins in the Tethys Realm during Mesozoic and Early Cenozoic.

The Silesian and the Subsilesian ridges were sources of felsic exotic blocks (granites and orthogneisses), while the Fore-Magura Ridge was the source of exotic mafic clasts in the Magura Basin during the Late Cretaceous–Paleogene. The Fore-Magura Ridge mafic exotics may represent an ocean floor assemblage, with the U–Pb zircon age of c. 615 Ma potentially representing magmatic crystallization of Paleoasian Ocean floor. This oceanic crust was probably obducted during later orogenic processes and incorporated into the accretionary prism. The metagabbro clasts from the Fore-Magura Ridge exhibit only semi-ductile deformation and no younger zircon rims, and represent the only possible provenance link to the Central Carpathians. The investigated felsic exotic clasts cannot be correlated in age with the Central (Inner) Western Carpathians, where Variscan granitoid magmatism and partial melting of the accretionary prism are pervasive. These data suggest the Silesian Basin was supplied from the eastern part of Brunovistulia.

References

Bailey SW (1980) Structures of layer silicates. In: Brindley GW, Brown G (eds) Crystal structures of clay minerals and their X-ray identification. Mineralogical Society, London, pp 1–123

Bónová K, Bóna J, Kovačik M, Mikuš T (2018) Heavy minerals and exotic pebbles from the Eocene flysch deposits of the Magura Nappe (Outer Western Carpathians, Eastern Slovakia): their composition and implications on the provenance. Turk J Earth Sci 27:64–88

Broska I, Petrik I, Be’eri-Shlevin J, Majka J, Bezak V (2013) Devonian/Missisipian I-type granitoids in the Western Carpathians: a subduction-related hybrid magmatism. Lithos 162–163:27–36

Budzyń B, Dunkley DJ, Kusiak MA, Poprawa P, Malata T, Skiba M, Paszkowski M (2011) SHRIMP U-Pb zircon chronology of the Polish Western Outer Carpatians source areas. Ann Soc Geol Poloniae 81:161–171

Burda J, Woskowicz-Ślęzak B, Klötzli U, Gawęda A (2019) Cadomian protolith ages of exotic mega blocks from Bugaj and Andrychów (Western Outer Carpathians, Poland) and their palaeogeographic significance. Geochronometria 46:25–36. https://doi.org/10.1515/geochr-2015-0102

Cathelineau M, Nieva D (1985) A chlorite solid solution geothermometer the Los Azufres (Mexico) geothermal system. Contrib Mineral Petrol 91:235–244

Chantraine J, Egal E, Thiéblemont D, Le Goff E, Guerrot C, Ballèvre M, Guennoc P (2001) The Cadomian active margin (North Armorican Massif, France): a segment of the North Atlantic Panafrican belt. Tectonophysics 331:1–18

Cieszkowski M, Kysiak T, Szczęch M, Wolska A (2017) Geology of the Magura Nappe in the Osielec area with emphasis on an Eocene olistostrome with metabasite olistoliths (Outer Carpathians, Poland). Ann Soc Geol Poloniae 87:169–182

Dalziel IWD, Dalla Salda LH, Gahagan LM (1994) Paleozoic Laurentia–Gondwana interaction and the origin of the Appalachian–Andean mountain system. Geol Soc Am Bull 106:243–252

Dobretsov NL, Buslov MM, Vernikovsky VA (2003) Neoproterozoic to Early Ordovician evolution of the Paleo-Asian Ocean: implications to the break-up of Rodinia. Gondwana Res 6:143–159

Dudek A (1980) The crystalline basement block of the Outer Carpathians in Moravia: Bruno-Vistulicum. Rozpr Čs Akad Věd Ř Mat přir Věd 90(8):3–85

Elkins LT, Groove TL (1990) Ternary feldspars experiments and thermodynamic models. Am Mineral 75(5):544–559

Finger F, Schitter F, Riegler G, Krenn E (1999) The history of the Brunovistulicum: total-Pb monazite ages from the metamorphic complex. Geolines 8:22–23

Fitton JG (2007) The OIB paradox. Geol Soc Am Spec Pap 430:387–412. https://doi.org/10.1130/2007.2430(20)

Frasl G, Finger F (1988) The “Cetic Massif” below the Eastern Alps—characterised by its granitoids. Schweiz Mineral Petrogr Mitt 68:433–439

Gawęda A, Golonka J (2011) Variscan plate dynamics in the circum-Carpathian area. Geodin Acta 24(3–4):141–155. https://doi.org/10.3166/ga.24.141-145

Gawęda A, Burda J, Klötzli U, Golonka J, Szopa K (2016) Episodic construction of the Tatra granitoid intrusion (Central Western Carpathians, Poland/Slovakia): consequences for the geodynamics of Variscan collision and Rheic Ocean closure. Int J Earth Sci 105:1153–1174

Gladkochub DP, Stanevich AM, Mazukabzov AM, Donskaya TV, Pisarevsky SA, Nicoll G, Motova ZL, Kornolova TA (2013) Early evolution of the Paleoasian Ocean: LA-ICP-MS dating of detrital zircon from Late Precambrian sequences of the southern margin of the Siberian craton. Russ Geol Geophys 54:1150–1163

Golonka J, Waśkowska A (2012) The Beloveža Formation of the Rača Unit in the Beskid Niski Mts. (Magura Nappe, Polish Flysch Carpathians) and adjacent parts of Slovakia and their equivalents in the western part of the Magura Nappe; remarks on the Beloveža Formation—Hieroglyphic Beds controversy. Geol Q 56(4):821–832

Golonka J, Waśkowska-Oliwa A (2007) Stratigraphy of the Polish Flysch Carpathians between Bielsko-Biała and Nowy Targ. Kwartalnik AGH Geologia 33(4/1):5–28

Golonka J, Krobicki M, Matyszkiewicz J, Olszewska B, Ślączka A, Słomka T (2005) Geodynamics of ridges and development of carbonate platform within the Carpathian realm in Poland. Slovak Geol Mag 11:5–16

Golonka J, Gahagan L, Krobicki M, Marko F, Oszczypko N, Ślączka A (2006) Plate Tectonic evolution and paleogeography of the Circum-Carpathian region. In: Golonka J, Picha F (eds) The Carpathians and their foreland: geology and hydrocarbon resources, vol 84. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir, Tulsa, pp 11–46

Golonka J, Pietsch K, Marzec P (2011) Structure and plate tectonic evolution of the northern Outer Carpathians. In: Closson D (ed) Tectonics. INTECH, Rijeka, pp 65–92

Hartz EH, Torsvik TH (2002) Baltica upside down: a new plate tectonic model for Rodinia and the Iapetus Ocean. Geology 30:255–258

Henry DJ, Guidotti CV, Thomson JA (2005) The Ti-saturation surface for low-to-medium pressure metapelitic biotites: implications for geothermometry and Ti substitution mechanism. Am Mineral 90:316–328

Holland T, Blundy J (1994) Non-ideal interactions in calcic amphiboles and their bearing on amphibole-plagioclase thermometry. Contrib Mineral Petrol 116:433–447

Jowett E (1991) Fitting iron and magnesium into the hydrothermal chlorite geothermometer. GAC/MAC/SEG joint annual meeting (Toronto). Abstract book 16, A62

Kalvoda J, Babek O, Fatka O, Leichman J, Melichar R, Nechyba S, Spacek P (2008) Brunovistulian terrane (Bohemian Massif, Central Europe) from late Proterozoic to late Paleozoic: a review. Int J Earth Sci 97:497–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-007-0183-1

Kennedy AK, Wotzlaw J-F, Schaltegger U, Crowley JL, Schmitz M (2014) Eocene zircon reference material for microanalysis of U–Th–Pb isotopes and trace elements. Can Mineral 52(3):409–421

Kröner A, Stipská P, Schulmann K, Jaeckel P (2000) Chronological constraints on the pre-Variscan evolution of the northeastern margin of the Bohemian Massif, Czech Republic. In: Franke W, Haak V, Oncken O, Tanner D (eds) Orogenic processes: quantification and modelling in the Variscan Belt, vol 179. Special publications. Geological Society, London, pp 175–198

Książkiewicz M (1977) Hypothesis of plate tectonics and the origin of the Carpathians. Ann Soc Geol Pol 47:329–353

Kuzmichev A, Kröner A, Hegner E, Dunyi Liu, Yusheng Wan (2005) The Shishkhid ophiolite, northern Mongolia: a key to the reconstruction of a Neoproterozoic island-arc system in central Asia. Precambr Res 138:125–150

Larionov AN, Andreitchev VA, Gee DG (2004) The Vendian alkaline igneous suite of northern Timan: ion microprobe U-Pb zircon ages of gabbros and syenite. Geol Soc London Memoirs 30:69–74

Leake BE, Woolley AR, Arps CES, Birch WD, Gilbert MC, Grice JD, Hawthorn FC, Kao A, Kisch HJ, Krivovichev VG, Linthout K, Laird J, Mandarino JA, Maresch WV, Nickel EH, Rock NMS, Schumacher JC, Smith DC, Stephenson NCN, Ungaretti L, Whittaker EJW, Youzhi G (1998) Nomenclature of amphiboles: report of the subcommittee of amphiboles of the International Mineralogical Association, Commission on new minerals and mineral names. Can Mineral 35:219–246

Linneman U, Gerdes A, Hofman M, Marko L (2014) The Cadomian Orogen: neoproterozoic to Early Cambrian crustal growth and orogenic zoning along the periphery of the West African Craton—Constraints from U–Pb zircon ages and Hf isotopes (Schwarzburg Antiform, Germany). Precambr Res 244:236–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2013.08.007

Linneman U, Pidal AP, Hofman M, Drost K, Quesada C, Gerdes A, Marko L, Gärtner A, Zieger J, Ulrich J, Krause J, Vickers-Rich P, Horak J (2018) A ~ 565 Ma old glaciation in the Ediacaran of peri-Gondwanan West Africa. Int J Earth Sci 107:885–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-017-1520-7

Linnemann U, D’Lemos RS, Drost K, Jeffries TE, Romer RL, Samson SD, Strachan RA (2008) Cadomian tectonics. In: McCann T (ed) The geology of Central Europe, vol 1. Precambrian and Paleozoic. Geological Society, London, pp 103–154

Ludwig KR (2012) Isoplot/Ex, v. 3.75. Berkeley Geochronology Center Special Publication, Berkeley, p 5

Massone HJ, Schreyer W (1987) Phengite geobarometry based on the limited assemblage with K-feldspar, phlogopite and quartz. Contrib Mineral Petrol 96:212–224

McDonough WF, Sun SS (1995) The composition of the Earth. Chem Geol 120:223–253

Michalik M, Budzyń B, Gehrels G (2006) Cadomian granitoid clasts derived from the Silesian Ridge (results of the study of gneiss pebbles from Gródek at the Jezioro Rożnowskie lake). Mineral Pol Spec Pap 29:168–171

Middlemost EAK (1985) Magmas and magmatic rocks. An introduction to igneous petrology. Longman Group Ltd., London

Neubauer F, Handler R (2000) Variscan orogeny in the Eastern Alps and Bohemian Massif: how do these units correlate ? Mitt Osterr Geol Ges 93:35–59

Oszczypko N (2006) Late Jurassic-Miocene evolution of the Outer Carpathian fold-and-thrust belt and its foredeep basin (Western Carpathians, Poland). Geol Q 50(1):169–194

Oszczypko N, Salata D (2005) Provenance analyses of the Late Cretaceous–Palaeocene deposits of the Magura Basin (Polish Western Carpathians)-evidence from the heavy minerals study. Acta Geol Pol 55(3):237–267

Paton C, Hellstrom J, Paul B, Woodhead J, Hergt J (2011) Iolite: freeware for the visualisation and processing of mass spectrometric data. J Anal Atom Spectr 26(12):2508–2518

Peccerillo A, Taylor SR (1976) Geochemistry of Eocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the Kastamonu area, northern Turkey. Contrib Mineral Petrol 58:63–81

Petrus JA, Kamber BS (2012) VizualAge: a novel approach to laser ablation ICP-MS U-Pb geochronology data reduction. Geostand Geoanal Res 36(3):247–270

Plašienka D, Grecula P, Putiš M, Hovorka D, Kovác M (1997) Evolution and structure of the Western Carpathians: an overview. In: Grecula P, Hovorka D, Putiš M (eds) Geological evolution of the Western Carpathians. Mineralia Slovaca, Bratislava, pp 1–24

Pointon MA, Cliff RA, Chew DM (2012) The provenance of Western Irish Namurian Basin sedimentary strata inferred using detrital zircon U-Pb LA-ICP-MS geochronology. Geol J 47(1):77–98

Poprawa P, Malata T, Pécskay Z, Kusiak MA, Banaś M, Paszkowski M (2006) Geochronology of the crystalline basement of the Western Outer Carpathians’ source areas—constraints from the K/Ar dating of mica and Th–U–Pb chemical dating of monazite from the crystalline ‘exotic’ pebbles. Geolines 20:110–112

Rehnström EF, Corfu F, Torsvik TH (2002) Evidence of late Precambrian (637 Ma) deformational event in the Caledonides of northern Sweden. J Geol 110:591–601. https://doi.org/10.1086/341594

Roberts D, Siedlecka A (2002) Timanian orogenic deformation along the northeastern margin of Baltic, northwest Russia and northeast Norway, and Avalonian–Cadomian connections. Tectonophysics 352:169–184

Schmidt MW (1992) Amphibole equilibria in tonalite as a function of pressure: an experimental calibration of the Al-in-hornblende barometer. Contrib Mineral Petrol 110:304–310

Skoczylas-Ciszewska K (1956) Budowa geologiczna strefy żegocińskiej. Acta Geol Pol 10(4):485–559 (in Polish)

Ślączka A, Kruglow S, Golonka J, Oszczypko N, Popadyuk I (2006) The general geology of the Outer Carpathians, Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. In: Golonka J, Picha F (eds) The Carpathians and their foreland: geology and hydrocarbon resources, vol 84. Memoir. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Tulsa, pp 221–258

Sláma J, Košler J, Condon DJ, Crowley JL, Gerdes A, Hanchar JM, Schaltegger U (2008) Plešovice zircon—a new natural reference material for U–Pb and Hf isotopic microanalysis. Chem Geol 249(1–2):1–35

Soejono I, Janoušek V, Žačková E, Sláma J, Konopásek J, Machek M, Hanžl P (2017) Long-lasting Cadomian magmatic activity along an active northern Gondwana margin: U–Pb zircon and Sr–Nd isotopic evidence from the Brunovistulian Domain, eastern Bohemian massif. Int J Earth Sci 106:2109–2129

Starzec K, Golonka J, Waśkowska A (2017) Rock formations at Karolówka Mount in the village of Istebna (the Silesian Beskids, Outer Western Carpathians)—geosites with large exotic rocks of nature conservation value. Chrońmy Przyrodę Ojczystą 73(4):271–283

Unrug R (1968) The Silesian cordillera as the source of clastic material of the flysch sandstone of the Beskid Śląski and Beskid Wyspowy ranges (Polish Western Carpathians). Ann Soc Geol Pol 38:155–164

Watson TM, Harrison EB (1983) Zircon saturation revisited: temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet Sci Lett 64:295–304

Wiedenbeck MAPC, Alle P, Corfu F, Griffin WL, Meier M, Oberli FV, Spiegel W (1995) Three natural zircon standards for U–Th–Pb, Lu–Hf, trace element and REE analyses. Geostand Geoanal Res 19(1):1–23

Wieser T (1952) The ophiolithe from Osielec. Ann Soc Geol Pol 21:319–327

Winchester JA, PACE TMR Network (2002) Palaeozoic amalgamation of Central Europe: new results from recent geological and geophysical investigations. Tectonophysics 360:5–22

Wiszniewska J, Krzeminska E, Dörr W (2007) Evidence of arc-related Svecofennian magmatic activity in the southwestern margin of the East European Craton inPoland. Gondwana Res 12:268–278

Żelaźniewicz A, Buła Z, Jachowicz M (2002) Neoproterozoic granites in the Upper Silesia massif of Bruno-Vistulicum, S Poland: U–Pb SHRIMP evidence. Schriftenreich der Deutschen Geologischen Gesselshaft 21:361–362

Żelaźniewicz A, Buła Z, Fanning M, Seghedi A, Żaba J (2009) More evidence on Neoproterozoic terranes in Southern Poland and southeastern Romania. Geol Q 53:93–124

Zonenshain LP, Kuzmin ML, Natapov LN (1990) Geology of the USSR: a Plate-Tectonic synthesis. In: Page BM (ed) Geodynamics series, vol 21. America Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C., pp 1–242

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Lidia Jeżak for her help during microprobe analyses. Comments of the handling editor Christian Dullo and two reviewers Ulf Linneman and Jürgen von Raumer led to clearer presentation of the paper and are deeply acknowledged. This study was supported by National Science Centre (NCN) Grant 2016/23/B/ST10/01896 given to JG. DC acknowledges support from research grant 13/RC/2092 from Science Foundation Ireland which is co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund and by PIPCO RSG and its member companies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gawęda, A., Golonka, J., Waśkowska, A. et al. Neoproterozoic crystalline exotic clasts in the Polish Outer Carpathian flysch: remnants of the Proto-Carpathian continent?. Int J Earth Sci (Geol Rundsch) 108, 1409–1427 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-019-01713-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-019-01713-x