Abstract

Purpose

While the existing knowledge base on the impact of prostate cancer (PC) and its treatment on sexuality and intimacy has been generated from Western populations, there is a lack of such evidence in the Asian context. This study aimed to explore men’s experiences of sex and intimacy after PC treatment in China.

Methods

This study adopted an interpretive descriptive design. Using purposive sampling, 13 PC patients were selected from a urology outpatient unit of a hospital in South China and proceeded with individual semi-structured telephone interviews. Each interview was transcribed verbatim and analyzed using constant comparison analysis.

Results

Four themes emerged from the interview data, including (a) encountering altered sexuality, (b) communication and sexual adjustments, (c) maintenance of quality intimate relationship, and (d) lack of sexual health support.

Conclusions

The findings revealed that PC treatment significantly impaired patients’ sexual functions, and their sexual health needs were mainly unmet by healthcare providers. There is a great need to design culturally relevant interventions to improve sexual health among this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is the second most common cancer in men, and there were 1.4 million diagnosed cases in 2020 [1]. PC patients in resource-limited countries usually receive radical prostatectomy and androgen deprivation therapy as primary treatments, depending on their disease stage [2]. Both treatments can result in sexual sequelae, typically erectile dysfunction, which is a persistent survivorship issue up to 15 years post-diagnosis [3, 4]. Sexual problems can also lead to challenges in intimate relationships [5, 6]. Sexual and intimacy issues have been identified as the most frequently reported unmet needs influencing quality of life in men with PC [7].

The literature has extensively documented the impact of PC and its treatment on sexuality, which is narrowly defined as the ability to engage in sexual intercourse. Research has shown that up to 97% of PC patients who were previously sexually active experienced post-treatment sexual dysfunction and thereby stopped their sex lives thereafter [8]. Numerous quantitative studies have determined the prevalence of sexual dysfunction induced by PC treatment, which is manifested in an array of symptoms, including erectile dysfunction (14–90%), loss of libido (18–45%), and penile shortening (19–71%) [9, 10]. Evidence has indicated that sexual dysfunction can cause impaired self-esteem and psychological distress, which may be exacerbated by men’s perceived diminished masculinity [3, 11]. Some qualitative studies have identified different strategies for adjusting to sexual dysfunction among men, for example, reframing masculinity, trying non-penetrative sexual practices, striving for acceptance of sexual changes, and seeking professional support [12,13,14].

Research on the psychosexual effects of PC has focused on sexuality, with relatively less emphasis on intimate relationships. Intimacy is a term for a person’s innermost qualities, which classically refers to the experience of “strong feelings of closeness, connectedness, and bonding” [15]. A few studies have examined intimacy changes in patients with PC, with most findings pertaining to reduced physical or relational intimacy [16, 17]. Altered intimacy has been reported to be associated with couples’ distress and well-being [18, 19].

While the existing knowledge base on the impact of PC and its treatment on sexuality and intimacy has been generated from Western populations, there is a lack of such evidence in the Asian context, particularly in China. Despite being among the lowest incidence areas globally, China has had a 3% annual increase in PC incidence rate due to an increased adoption of prostate-specific antigen screening and westernized lifestyles [1, 20]. Evidence has suggested that the perception of how individuals explain, experience, and cope with sexual dysfunction is determined by cultural values, more specifically relating to positive or negative sexual cognitions [21, 22]. Despite this, PC patients as a rapidly growing population in China have received little research attention relative to female cancers regarding sexuality and intimacy [23, 24]. One qualitative systematic review highlighted gender-specific influences on attitudes toward and experiences of sex in older adults, especially male-dominated sexual relationships in non-Western countries [25]. An investigation of the sexual and intimate experiences of Chinese men affected by PC and its treatment is thereby urgently needed. The qualitative method is appropriate for such inquiry to generate unique insights into men’s narratives of the phenomena they have experienced. Having an understanding of their perspectives on sexual and intimate experiences is the first important step before designing tailored interventions to aid healthcare professionals (HCPs) in managing men’s post-treatment changes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore men’s experiences of sex and intimacy after PC treatment in China.

Methods

Design

This study adopted an interpretive description, which is an applied qualitative approach allowing the investigation of a clinical phenomenon to identify recurrent patterns within subjective perceptions [26]. This approach is philosophically underpinned by constructivism and naturalism, acknowledging the constructed and contextualized nature of human experiences [27]. It is particularly appropriate for generating knowledge to inform clinical understanding and practice [26]. Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the university (HSEARS20200624001-01) and the hospital (SYSEC-KY-KS-2020–154-001), respectively. Signed written consent was obtained from the participants before the study. This paper’s reporting followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist (see Appendix 1) [28].

Setting and participants

The participants were recruited from a urology outpatient unit of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China, between November 2020 and March 2021. Purposive sampling with maximum variance was used to select participants with different ages, length of marriage, treatment types, and time since diagnosis. Patients were included if they were (a) diagnosed with PC, (b) treated with prostatectomy and/or androgen deprivation therapy for at least three months [2, 29], (c) sexually active (defined as engaging in sexual intercourse by direct genital contact) within one year before the diagnosis, and (d) able to communicate in Mandarin or Cantonese. Patients who had a history of mental disease (as determined by surgeons) or were unwilling to share their experiences related to sexuality and intimacy were excluded. The sample size was considered adequate based on the pragmatic concept of “information power,” which was justified by the narrow research questions, sample specificity, and quality of dialogue and analysis [30].

Procedures

The researcher (WT), who was a master’s-prepared nurse with training in qualitative research, conducted participant recruitment, data collection, and analysis of this study. The researcher approached potentially eligible participants after they attended medical consultations in the urology outpatient unit. Once they were screened for eligibility and consented to participants, the researcher proceeded to brief the study, obtain signed consent, and collect demographic and clinical data. The virtual interviews were originally planned to take place through WeChat during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the researcher found that the participants’ most preferred method was telephone interviews due to their older age. Telephone interviews have been proven as a feasible method for exploring sensitive topics as they can lessen emotional distress during the interviews [31].

A semi-structured interview schedule (see Appendix 2) was used to guide the interview process, which was developed based on a literature review and the clinical expertise of the research team, including a urologist, a sex therapist, and a nurse expert. The schedule covered topics that included the impact of PC and its treatment on sexuality, perceived changes in intimacy, coping strategies, and support from HCPs. After on-site recruitment, the researcher contacted the participants before the formal telephone interviews to engage them in casual conversations for rapport building. In the formal interviews with no one else present, the researcher started with warm-up questions to put the participants at ease, followed by the main questions, such as “Would you mind discussing your sexual changes with me?” The participants were probed when appropriate, for example, “Would you mind giving me more examples?” The sequence of the interview questions was not fixed to better align with each participant’s responses. The average duration of the interviews was 25 min.

Data analysis

According to the interpretive description design, data collection and analysis occurred concurrently [27]. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim in Simplified Chinese in Microsoft Word files. Only quotations supporting the findings were translated into English. Data analysis was performed following the constant comparative method, which was facilitated by Microsoft Excel 2016 [27, 32]. Prior to the formal coding, data immersion was performed, including reviewing the transcripts closely and writing a synopsis of each interview, instead of coding prematurely. Inductive analysis began with initial coding to summarize the key attributes of the relevant transcript texts, which reflected possible common patterns and their relationships [26, 27]. Once the patterns of codes were merged, they were grouped into themes and sub-themes. Constant comparisons within-case and cross-case followed to compare new data with emerging themes from previous interviews [27]. The researcher (WT) was the primary data analyst, and another researcher (CHL) who was experienced in qualitative research analyzed the first few transcripts independently. Regular meetings among these two researchers (WT and CHL) were held to reach a consensus on the coding scheme and to develop preliminary themes and sub-themes throughout the data analysis process. The coding results were critically reviewed and finalized by the research team after multiple discussions.

Rigor

The study followed Morse’s (2015) strategy to achieve both validity and reliability [33]. To address the issue of validity, a critical review of the literature, data collection, and analysis was ensured to be aligned with the study’s aim. Furthermore, the participants were purposively selected with maximum variance to ensure that the sample was the best representation of the population, providing an in-depth understanding of the study topic. Concurrent data collection and analysis was conducted to verify the validity of the study. The researcher received sufficient training in qualitative interviews and conducted multiple mock interviews supervised by an experienced qualitative researcher and a sex therapist, along with a debriefing after each interview with the team, which further enhanced validity. Reliability was achieved by the researcher as the interviewer and a semi-structured interview guide, which increased the consistency of data collection. The use of a second coder facilitated the establishment of coding reliability and ensured the rigor of the findings.

Findings

Participants’ characteristics

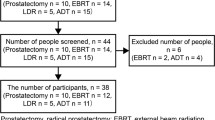

Of the 23 patients who were approached, three were screened as ineligible for the study due to asexuality more than one year before PC, while seven were excluded because they were uncomfortable with the sexual topic (n = 3), had a poor health status (n = 2), and had a clash of time schedules (n = 2). Finally, 13 PC patients (mean age = 69.2 years old) participated in this study (see Table 1). The participants were exclusively married, and their years of marriage ranged from 28 to 54 years. The mean time since diagnosis was 17 months, varying from three months to 5.5 years. Over half of the participants were diagnosed at the advanced stage (stage III or IV) and had undergone androgen deprivation therapy alone.

Themes

An analysis of the participants’ interviews identified four themes: (a) encountering altered sexuality; (b) communication and sexual adjustments; (c) maintenance of a quality intimate relationship; and (d) lack of sexual health support (see Appendix 3).

Encountering altered sexuality

Despite all the participants reporting normal sexual functions and maintaining regular sexual activities prior to their PC diagnosis, all of them experienced sexual dysfunction after PC treatment that were manifested in erectile dysfunction, a decline in sexual desire, penis shrinkage, and ejaculation deficiency, with erectile dysfunction being the most reported symptom. The inability to achieve an erection precluded the participants from engaging in penetrative sexual intercourse. For example, as one participant described:

“I still think about it [sex], but I was unable to get and keep an erection for sex. After attempting several times, I gave it up.” (76 years old, 4 months post-diagnosis).

The participants attributed these changes to multiple factors, with PC and its treatment mostly being the main reasons. Some cited aging as a synergic factor of the changes. As one 74-year-old participant (3 years post-diagnosis) described:

“For people aged 72 or 73, they lose their sexual functions and don’t even think about it anymore.”

Several participants reported that psychological burdens contributed to their sexual dysfunction, as they worried that having sex could deteriorate their health. For instance:

“It’s only been three months [since the surgery], I don’t have any feelings for a sex life, not at all…because a sex life might result in a recurrence of my disease. I am pressured by this aspect.” (66 years old, 3 months post-diagnosis).

When probed for impacts of altered sexuality, the participants usually briefly spoke of negative emotions associated with asexuality but expressed that they had accepted it:

“I had no ideas in my mind. I just felt that there was no way [I could avoid sexual problems].” (67 years old, 1 year post-diagnosis).

Most of the participants explained that survival was the priority and a sex life was less important. One participant stated:

“I don’t think about these things [sex]. I only want to cure the cancer.” (61 years old, 2 years post-diagnosis).

Communication and sexual adjustments

The vast majority of the participants did not disclose sexual issues to their partners as they felt too embarrassed to communicate about sexual matters. They assumed that their partners would know the condition of erectile dysfunction and understand and accept the sexual changes induced by PC treatment. For instance, one patient stated:

“We don’t need to talk about this, as she knows my situation [erectile dysfunction]…. Our relationship is good so that we don’t need any communication. Anyway, she understands this.” (74 years old, 3 years post-diagnosis).

Some patients disclosed sexual issues only if asked by their partners. For example, as one patient explained:

“After my surgery, she knew the situation [erectile dysfunction], and then I told her about it. She said it was okay and told me not to think too much.” (77 years old, 5.5 years post-diagnosis).

Regarding sexual adjustment, most of the participants indicated that they did not use any approaches to meet their sexual needs and chose to suppress their sexual desires. One 73-year-old participant two years post-diagnosis said:

“I didn’t take any medications or use any methods like others. I think that I might not have any sexual needs after the surgery. It should have gone away.”

Interestingly, three participants reported experiences of attempting to seek their spouse’s help or take medications to achieve an erection, but they found that these methods were unsuccessful. For example, one participant shared the distressing experience of taking Viagra for his erectile dysfunction:

“I bought the pill at the pharmacy and then took it without telling my wife. But it was useless and I still couldn’t get an erection. It [the penis] looked soft exactly the same as before. I also felt distressful side effects, I had pain in my blood vessels and afterwards in my whole body.” (67 years old, 1 year post-diagnosis).

Maintenance of quality intimate relationship

Despite being affected by a decline in their sexual functions, all the participants perceived a positive impact of disease and treatment on their intimate relationship. They felt that their partners were supportive and their intimate relationship was as good as before the disease or enhanced after the disease. For example, one participant said:

“I think we became more intimate after the disease. Before I had cancer, we were used to not communicating very often. Now, I am glad that she takes care of me a lot. I even think about how I can repay her. I also express my concerns now and sometimes try to do some housework to relieve her.” (73 years old, 2 years post-diagnosis).

Almost all the participants said that the main ways of expressing love and care were through practical actions in daily living, such as applying massage and cooking, rather than saying “I love you” directly. One participant said:

“After my surgery…I usually massage my wife’s legs and feet before we sleep.” (73 years old, 2 years post-diagnosis).

Another participant shared:

“As I used to not eat meat, she chopped up the meat to make nutritious soup for me…. She used to not do this kind of thing for me.” (67 years old, 7 months post-diagnosis).

Some participants also explained that Chinese cultural norms discouraged them from expressing intimacy. As one participant noted:

“Our town is very conservative, not like the big cities. Because of cultural reasons, my wife is introverted and doesn’t like to say intimate things.” (61 years old, 2 years post-diagnosis).

Other participants commented on gender-related differences in expressing intimacy:

“Men and women are different. Women are more meticulous. We men are careless…. When I need to see the doctor, I need to go out around 4:30 in the morning. My wife will get up much earlier, like 2:30 a.m., to cook breakfast for me.” (67 years old, 1 year post-diagnosis).

Lack of sexual health support

The participants perceived that very limited sexual health-related information was provided by HCPs during and after their treatment. According to the participants, sexual matters were raised by HCPs when treatment-related sexual side effects were explained before consenting to receive a particular treatment. After treatment, they had few opportunities to discuss sexual problems and potential sexual rehabilitation options with HCPs. Few participants attempted to have conversations about sexual problems with HCPs. For example, as one participant mentioned:

“The doctor didn’t say anything. The nurses didn’t say anything. Only the nurse in charge of me said it [the surgery] might affect my sexual functions…she just said those few words.” (71 years old, 4 months post-diagnosis).

The participants described several barriers to initiating a discussion of sexual topics with HCPs. Most of them described feeling too embarrassed to ask about sexual issues during medical consultations. Just one participant shared:

“I see the doctor once a month. Sometimes when I see him, I would like to ask if there is any way to solve my sexual problems. But I feel too embarrassed to ask him.” (73 years old, 2 years post-diagnosis).

Some participants expressed worries about wasting the doctor’s time asking about sexual matters. For example:

“You don’t have much time for the consultation. Too many people there are waiting [to see the doctor], and how could I ask about this kind of thing?” (67 years old, 7 months post-diagnosis).

Despite unsuccessful attempts to talk about sexual problems with HCPs, many participants expressed a desire to know more sexual health information but felt that the appropriate time to initiate conversations on sexuality was when their health status became stable. For example, one participant suggested:

“I would consider other [sexual] issues on the basis of a healthy body. Now I focus on being healthy and living a normal life.” (79 years old, 1 year post-diagnosis).

Discussion

By exploring men’s experiences of sex and intimacy after PC treatment, this study identified some key findings. Concurring with the literature in Western countries, this study found that the participants had similar experiences of sexual dysfunction following treatment [3, 10]. The participants also mentioned multiple factors that contributed to their acceptance of sexuality changes, including shifting their priority to survival, fear of cancer recurrence due to having sex, and aging, all of which have been previously reported [34, 35]. Despite similar findings on men’s acceptance of sexual changes in Western and Chinese contexts, the present findings may reflect unique cultural interpretations of sex from a traditional Chinese perspective. Chinese men are encouraged to abstain from sex to preserve their health because males’ seminal essence is deemed highly precious and avoiding its loss can prevent disease [36]. They also do not regard sexuality as a priority with increasing age since sex is a means of procreation to preserve the family line rather than for pleasure [37].

The vast majority of the participants in this study did not disclose sexual issues to their partners, which was inconsistent with Western studies that found that some PC men talked about sexual issues with their spouses [13, 38]. Chinese men’s sexual experiences have long been influenced by Confucianism, which emphasizes male dominance in sexual initiation and female submissive to men [37]. The participants in this study did not share their sexual problems or engage in help-seeking behavior as they assumed their spouses would know about them after years of marriage. Disclosing sexual dysfunctions and help-seeking behavior among older Chinese men are viewed as not desirable as they imply a loss of male dominance and can damage men’s identity [39]. Disclosing sexual difficulties to female partners is viewed as “losing face” or “being undignified” [40]. The study also found that the men suppressed their sexual desire for health reasons rather than actively sought various methods to restore their sexual health, further reflecting negative sexual cognitions pertaining to the procreation nature of sex [37, 40].

This study showed that the men maintained a quality intimate relationship with their partners, which is in contrast to most findings in the literature. One possible explanation for such discrepancy is that expressions of intimacy differ between Western and Chinese cultures. While Western males’ perception of physical intimacy is intricately related to sexual intercourse and non-penetrative behaviors, such as hugging and kissing [34], Chinese males regard intimacy as related to relationship intimacy, which is expressed through companionship and practical support [37].

The study revealed limited opportunities to discuss sexual matters during medical encounters, resulting in the men’s sexual health information needs being largely unmet by HCPs, which is in line with the literature on female Chinese cancer patients [23, 24]. This study also identified several barriers to help-seeking behavior, including feeling too embarrassed to talk about sexual-related issues and worrying about wasting the doctor’s time. These findings can be explained by Chinese culture, which regards sexuality as a private matter that should not be discussed in public [37, 41]. Previous research has documented that HCPs are less likely to initiate the topic due to their overburdened workload and noisy consulting environment [42], and this study’s findings further add to this evidence.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study recruited participants from a single hospital in South China, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings to the larger population. Second, the participants were married and had heterosexual partners, which does not represent PC patients who are unmarried or sexual minorities. Third, the participants reported good martial relationships, which might not apply to those who had pre-existing relationship problems and faced greater challenges in adjusting to sex and intimacy changes. Finally, the study was cross-sectional in nature, and thus, changes in sexuality and intimacy experienced by the PC patients could not be determined.

Clinical implications

The present findings lend support for a need to develop culturally relevant sexual health programs and provide resources to assist patients in lessening the impact of the disease and its treatment on sexuality. As evidence has accumulated that couples-based education and counseling programs are effective in improving sexual communication and sexual adjustment for Western couples [41, 43, 44], cultural adaptation of successful programs can be considered for the Chinese population in the future. Additionally, the study showed that PC patients’ sexual issues are under-addressed in the cancer care system, indicating a significant service gap in sexual education for this population. Considering that not addressing sexual dysfunction in cancer patients appears to be overlooked during cancer care, and that sexuality is a taboo topic to discuss in public, HCPs should be provided with systematic training to equip them with sexual knowledge and communication skills so that they can feel confident in initiating consultations on sexual health. A recent review showed that regardless of the intensity and modes of training courses, sexual education can improve HCPs’ ability to deal with patients’ sexual problems [45].

Conclusion

The findings revealed that PC treatment significantly impaired patients sexual functions, and their sexual health needs were mainly unmet by HCPs. There is a great need to design culturally relevant interventions to improve sexual health among this population.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I et al (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249

Zhu Y, Wang HK, Qu YY, Ye DW (2015) Prostate cancer in East Asia: evolving trend over the last decade. Asian J Androl 17(1):48–57

Chambers SK, Chung E, Wittert G, Hyde MK (2017) Erectile dysfunction, masculinity, and psychosocial outcomes: a review of the experiences of men after prostate cancer treatment. Transl Angrol Urol 6(1):60–68. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.08.12

Mazariego CG, Juraskova I, Campbell R, Smith DP (2020) Long-term unmet supportive care needs of prostate cancer survivors: 15-year follow-up from the NSW Prostate Cancer Care and Outcomes Study. Support Care Cancer 28(11):5511–5520

Wassersug RJ (2016) Maintaining intimacy for prostate cancer patients on androgen deprivation therapy. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 10(1):55–65

Maharaj N, Kazanjian A (2021) Exploring patient narratives of intimacy and sexuality among men with prostate cancer. Couns Psychol Q 34(2):163–182

Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, Nabi G (2015) Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19(4):405–418

Fode M, Mosholt KS, Nielsen TK, Tolouee S, Giraldi A et al (2020) Sexual motivators and endorsement of models describing sexual response of men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer. J Sex Med 17(8):1538–1543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.04.006

Jenkins LC, Mulhall JP (2016) Impact of prostate cancer treatments on sexual health. In Mydlo JH, Godec GJ (ed.) Prostate Cancer, Science and Clinical Practice, Second Edition

Lehto US, Tenhola H, Taari K, Aromaa A (2017) Patients’ perceptions of the negative effects following different prostate cancer treatments and the impact on psychological well-being: a nationwide survey. Br J Cancer 116(7):864–873. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.30

Hilger C, Schostak M, Neubauer S, Magheli A, Fydrich T et al (2019) The importance of sexuality, changes in erectile functioning and its association with self-esteem in men with localized prostate cancer: data from an observational study. BMC Urol 19(9):1–8

Hanly N, Mireskandari S, Juraskova I (2014) The struggle towards “the New Normal”: a qualitative insight into psychosexual adjustment to prostate cancer. BMC Urol 14(1):1–10

Wassersug RJ, Westle A, Dowsett GW (2017) Men’s sexual and relational adaptations to erectile dysfunction after prostate cancer treatment. Int J Sex Health 29(1):69–79

Smith AB, Wittmann D, Saint Arnault D (2020) The ecology of patients’ sexual health adjustment after prostate cancer treatment: the influence of the social and healthcare environment. Oncol Nurs Forum 47(4):469–478

Sternberg RJ (1986) A triangular theory of love. Psychol Rev 93(2):119–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.119

Walker LM, Santos-Iglesias P, Robinson J (2018) Mood, sexuality, and relational intimacy after starting androgen deprivation therapy: implications for couples. Support Care Cancer 26(11):3835–3842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4251-9

Fernández-Sola C, Martínez-Bordajandi Á, Puga-Mendoza AP, Hernández-Padilla JM, Jobim-Fischer V et al (2020) Social support in patients with sexual dysfunction after non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a qualitative study. Am J Mens Health 14(3):1–12

Dieperink KB, Mark K, Mikkelsen TB (2016) Marital rehabilitation after prostate cancer–a matter of intimacy. Int J Urol Nurs 10(1):21–29

Manne SL, Kissane D, Zaider T, Kashy D, Lee D et al (2015) Holding back, intimacy, and psychological and relationship outcomes among couples coping with prostate cancer. J Fam Psychol 29(5):708–719

Culp MB, Soerjomataram I, Efstathiou JA, Bray F, Jemal A (2020) Recent global patterns in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol 77(1):38–52

Bhavsar V, Bhugra D (2013) Cultural factors and sexual dysfunction in clinical practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat 19(2):144–152

Newlands RT, Brito J, Denning DM (2020) Cultural considerations in the treatment of sexual dysfunction. In: Benuto LT, Gonzalez FR, Singer J (eds) Handbook of Cultural Factors in Behavioral Health, 1st edn. Springer, Cham, pp 345–361

Yuan X, Wang J, Bender CM, Zhang N, Yuan C (2020) Patterns of sexual health in patients with breast cancer in China: a latent class analysis. Support Care Cancer 28(11):5147–5156

Gong N, Zhang Y, Suo R, Dong W, Zou W et al (2021) The role of space in obstructing clinical sexual health education: a qualitative study on breast cancer patients’ perspectives on barriers to expressing sexual concerns. Eur J Cancer Care 30:e13422. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13422

Sinković M, Towler L (2019) Sexual aging: a systematic review of qualitative research on the sexuality and sexual health of older adults. Qual Health Res 29(9):1239–1254

Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K (2004) The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Methods 3(1):1–11

Thorne S (2016) Interpretive Description: qualitative research for applied practice. Second Edition Routledge

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357

Schover LR (2015) Sexual healing in patients with prostate cancer on hormone therapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 35:e562–e566

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD (2016) Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 26(13):1753–1760

Mealer M, Jones J (2014) Methodological and ethical issues related to qualitative telephone interviews on sensitive topics. Nurs Res 21(4):32–37

Ose SO (2016) Using Excel and Word to structure qualitative data. J Appl Soc Sci 10(2):147–162

Morse JM (2015) Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res 25(9):1212–1222

Walker LM, Robinson JW (2010) The unique needs of couples experiencing androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Sex Marital Ther 36(2):154–165

Carlsson S, Drevin L, Loeb S, Widmark A, Lissbrant F, Robinson D et al (2016) Population-based study of long-term functional outcomes after prostate cancer treatment. BJU Int 117(6B):E36-45

Zhang EY (2015) The loss of jing (seminal essence) and the revival of yangsheng (the cultivation of life). In The Impotence Epidemic. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 135-165

Yan E, Wu AMS, Ho P, Pearson V (2011) Older Chinese men and women’s experiences and understanding of sexuality. Cult Health Sex 13(9):983–999

Collaço N, Wagland R, Alexis O, Gavin A, Glaser A, Watson EK (2021) The experiences and needs of couples affected by prostate cancer aged 65 and under: a qualitative study. J Cancer Surviv 15(2):358–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00936-1

Ho CC, Singam P, Hong GE, Zainuddin ZM (2011) Male sexual dysfunction in Asia. Asian J Androl 13(4):537–542

Sun Y, Liu Z (2007) Men’s health in China. J Mens Health Gend 4(1):13–17

Zhang H, Yip AWC, Fan S, Yip PSF (2013) Sexual dysfunction among Chinese married men aged 30–60 years: a population-based study in Hong Kong. Urology 81(2):334–339

Yan J, Yao J, Zhao D (2021) Patient satisfaction with outpatient care in China: a comparison of public secondary and tertiary hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care 33(1):1–7

Zeng YC, Li Q, Wang N, Ching SSY, Loke AY (2011) Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care in cancer patients. Cancer Nus 34(2):E14–E20

Walker LM, Hampton AJ, Wassersug RJ, Thomas BC, Robinson JW (2013) Androgen deprivation therapy and maintenance of intimacy: a randomized controlled pilot study of an educational intervention for patients and their partners. Contemp Clin Trails 34(2):227–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2012.11.007

Verrastro V, Saladino V, Petruccelli F, Eleuteri S (2020) Medical and health care professionals’ sexuality education: state of the art and recommendations. Int J Environ Res 17(7):2186

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation of participants and staff from the urology department for their great support in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WT, CHL, and DW contributed to the conception and design of the study. WT performed participant recruitment, data collection, and analysis. WT drafted the manuscript, and all authors revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the Ethics committees of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HSEARS20200624001-01) and the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (SYSEC-KY-KS-2020–154-001).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

All participants consented to the research and subsequent publications.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Cheng, HL., Wong, P.K.K. et al. Men’s experiences of sex and intimacy after prostate cancer treatment in China: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 30, 3085–3092 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06720-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06720-w