Abstract

Purpose

This study evaluated the risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) in patients with cancer who received denosumab or zoledronic acid (ZA) for treating bone metastasis.

Methods

The medical records of patients were retrospectively reviewed. Patients who did not undergo a dental examination at baseline were excluded. The primary endpoint was a comparison of the risk of developing MRONJ between the denosumab and ZA groups. Propensity score matching was used to control for baseline differences between patient characteristics and compare outcomes for both groups.

Results

Among the 799 patients enrolled, 58 (7.3%) developed MRONJ. The incidence of MRONJ was significantly higher in the denosumab group than in the ZA group (9.6% [39/406] vs. 4.8% [19/393], p = 0.009). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed that denosumab treatment (hazard ratio [HR], 2.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.65–5.25; p < 0.001) and tooth extraction after starting ZA or denosumab (HR, 4.26; 95% CI, 2.38–7.44; p < 0.001) were significant risk factors for MRONJ. Propensity score–matched analysis confirmed that the risk of developing MRONJ was significantly higher in the denosumab group than in the ZA group (HR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.17–5.01; p = 0.016).

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that denosumab poses a significant risk for developing MRONJ in patients treated for bone metastasis, and thus these patients require close monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bone metastasis is commonly found in patients with advanced cancers; it leads to clinically important complications, such as pain, hypercalcemia, spinal cord compression, and fractures [1, 2]. Skeletal-related events remarkably decrease the quality of life of patients with bone metastasis. Since recent progress in cancer treatments has prolonged the survival of patients with advanced cancer, the prevalence of bone metastasis in cancer patients has inevitably increased, accompanied by a further increase in the significance of corresponding treatments [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Zoledronic acid (ZA) is a potent bisphosphonate (BP) that has a high affinity for hydroxyapatite; it is internalized by osteoclasts during resorption, leading to inhibition of osteoclast function [13]. Denosumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) ligand (RANKL) [14]. Both ZA and denosumab demonstrated efficacy in preventing skeletal complications in patients with bone metastasis secondary to solid tumors or osteolytic lesions of multiple myeloma. Despite the usefulness of bone-modifying agents (BMAs), significant safety concerns including hypocalcemia [15] and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) have been reported as severe side effects associated with their use [16]. MRONJ causes severe pain and markedly reduces patient quality of life; therefore, collaborative management with healthcare providers, including dentists, is recommended. This approach will make it possible to conduct appropriate monitoring, assessment, and treatment in early-stage MRONJ [17,18,19,20]. Thus, it is necessary to accumulate more information on the risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Several risk factors and comorbid conditions that contribute to the development of MRONJ include BMAs, duration of therapy, dental extraction and other oral surgical procedures, periodontal disease, oral health status, tobacco use, angiogenesis inhibitors, corticosteroids, diabetes, and increasing age [17,18,19, 21, 22]. Reported risk evaluations for BMAs remain controversial. Although a recent meta-analysis based on the results from randomized controlled trials reported that denosumab was associated with a significantly higher risk of developing MRONJ than ZA [23], this significant difference between the two drugs was not shown in other meta-analyses [24,25,26,27]. Furthermore, in real-world clinical practice, preventing MRONJ is more complex. This complexity is due to the treatments, including those for various patients with more risk factors, such as older patients, unscheduled dental treatments, diabetic complications, and the concomitant use of medications that increase the risk of MRONJ. However, there is little information available regarding risk evaluation comparing BMAs in real-world clinical practice. Moreover, no available studies have compared the risk of MRONJ between denosumab and ZA based on adjusted baseline patient characteristics. In this study, to reduce the impact of potential bias in an observational study, we conducted a propensity score–matched analysis in a clinical setting to compare the risk of developing MRONJ between patients with cancer bone metastasis treated with the BMAs denosumab or ZA.

Methods

Study design, setting, and patient population

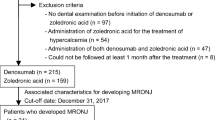

This retrospective observational study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Internal Review Board of the Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (approval number: k191010). Due to the retrospective nature of this work, informed consent was waived for the individual participants included in the study in accordance with the ethical standards of the Internal Review Board of the Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, and the research plan was published on the homepage of the hospital in accordance with the guaranteed opt-out opportunity. Adult patients were eligible if they were diagnosed with cancer, presented with at least one bone metastasis or osteolytic lesion, and started denosumab or ZA treatment at Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital after dental examinations by dentists between July 1, 2011, and October 31, 2019. The following comprised the exclusion criteria: lack of dental examination before beginning denosumab or ZA treatment, use of ZA for hypercalcemia treatment, could not be followed up 1 month after the start of BMA treatment, or history of radiation therapy for the jaw.

Bone metastasis treatment procedure

When needed and following dental examination, patients underwent dental procedures (such as tooth extraction) to minimize the risk of MRONJ development prior to initiating BMA treatment. All patients were administered 120 mg denosumab subcutaneously every 4 weeks or 4 mg ZA intravenously every 3–4 weeks. Patients with decreased kidney function (creatinine clearance ≤ 60 mL/min) were administered a reduced ZA dose based on their creatinine clearance, as recommended by the manufacturer. We divided the study subjects into two groups: patients who received denosumab (denosumab group) and patients who received ZA (ZA group).

Data collection and assessment

All data were collected from the electronic medical record system. We evaluated information regarding sex, age, weight, cancer type, comorbidities, tooth extraction before and after starting BMA treatment, concomitant medications, type of BMA, number of treatment courses, and outcomes of treatment for MRONJ. To minimize potential bias in evaluating factors associated with MRONJ development, study participants were limited to those examined by dentists before initiating BMA treatments, because poor oral health status has been reported as a remarkable risk factor for MRONJ [17,18,19,20]. Moreover, it was recommended that all patients routinely visit dental clinics after the initiation of BMA treatment. If the patients were considering invasive dental procedures, such as tooth extraction, after commencing BMA treatment, they were asked to consult with dentists in our hospital. After starting BMA treatment, patients who complained of dental symptoms, including pain or oral discomfort, consulted a dentist according to the request of the attending physician. In unavoidable situations, including accidental root fracture or acute exacerbation of periodontal disease, tooth extraction was performed. MRONJ was diagnosed by dentists in our hospital based on clinical and radiographic findings, according to the criteria stated in the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) position paper [20, 28], and the cut-off date when the patients were diagnosed as MRONJ was December 31, 2019. Since switching from ZA to denosumab can increase the risk for developing MRONJ, for patients who received ZA followed by denosumab, the cut-off date was the day of switching to denosumab treatment. Similarly, in patients who received denosumab followed by ZA, the cut-off date was the day of switching to ZA. Thus, all MRONJ cases in this study were assessed between they received only denosumab or ZA. The primary endpoint was a comparison of the risk of developing MRONJ between the denosumab and the ZA groups, whereas secondary endpoints included the risk factors for developing MRONJ and the relationship between risk factors and the time to MRONJ development.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as numbers (percentages) and were compared between groups using the chi-square test. Continuous data are presented as medians (interquartile ranges), and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the groups. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was employed to analyze the associated factors for developing MRONJ. Variables with a p-value < 0.05 in the univariate analyses were applied to the multivariate analysis. The cumulative incidences of MRONJ were described by the Kaplan–Meier method, and the differences of the time to development of MRONJ were compared with the log-rank test.

To adjust for the other baseline factors, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by propensity score matching. We estimated the propensity score by modeling the probability of being in the ZA group versus the denosumab group. The following variables were included in the regression model: sex, age, cancer type, tooth extraction before starting BMA treatment, comorbidity with diabetes, concomitant use of antiangiogenic agents, concomitant use of corticosteroids, and tooth extraction after starting BMA treatment. To reduce bias with these potential confounding factors, 1:1 matching (without replacement) in the two treatment groups was achieved using the nearest neighbor method with a 0.20-width caliper of standard deviation of the logit of propensity scores. The matched data were analyzed to confirm the robustness of the primary analysis results. We used JMP add-in package version 13.2.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for all statistical analyses, and two-tailed p-values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between July 2011 and October 2019, 1192 consecutive adult patients with cancer bone metastasis were administered denosumab or ZA (Fig. 1). Among them, 799 patients (406 in the denosumab group and 393 in the ZA group) met the inclusion criteria, and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Three hundred and ninety-three patients were excluded because they received ZA for the treatment of hypercalcemia (n = 163), lacked dental examinations before starting denosumab or ZA treatment (n = 148), or could not be followed up for 1 month after the start of BMA treatment (n = 82). Before propensity score matching, the proportion of male patients was significantly higher in the denosumab group than in the ZA group. The proportions of patients with lung cancer or prostate cancer were higher in the denosumab group, whereas those with multiple myeloma were higher in the ZA group. The proportion of patients who received concomitant corticosteroids was significantly higher in the denosumab group than in the ZA group. The incidence of MRONJ in all study subjects was 7.3% (58/799) and was significantly higher in the denosumab group than in the ZA group (9.6% [39/406] vs. 4.8% [19/393], p = 0.009]. Stage 0, 1, 2, and 3 MRONJ were developed in 1, 9, 27, and 2 patients in the denosumab group, and in 0, 4, 14, and 1 patients in the ZA group, respectively. After propensity score matching, patient characteristics were well balanced based on all measured variables (Table 1). In the propensity score–matched cohort, the incidence of MRONJ in the denosumab group was also significantly higher than that in the ZA group (9.7% [24/248] vs. 4.8% [12/248], p = 0.038).

Risk factors for MRONJ

Univariate analysis showed that treatment with denosumab (hazard ratio [HR], 2.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.53–4.77; p < 0.001), tooth extraction after starting BMAs (HR, 4.84; 95% CI, 2.78–8.24; p < 0.001), tooth extraction before starting BMAs (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.37–3.93; p = 0.002), comorbidity with diabetes (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.13–0.84; p = 0.014), and concomitant use of antiangiogenic agents (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.06–3.10; p = 0.031) were significantly associated with the development of MRONJ in cancer patients who received BMA treatment (Table 2). Subsequent multivariate Cox proportional hazards model analysis also showed that denosumab treatment (HR, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.65–5.25; p < 0.001) and tooth extraction after starting BMAs (HR, 4.26; 95% CI, 2.38–7.44; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with a risk of developing MRONJ in cancer patients who received BMA treatment.

We also performed propensity score matching to balance patient characteristics between the denosumab and ZA groups. There were no significant differences in the factors between the two groups (Table 1). In the propensity score–matched cohorts, the risk of developing MRONJ was significantly higher in the denosumab group than in the ZA group (HR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.17–5.01; p = 0.016; Table 2). Kaplan–Meier curves of the time to MRONJ onset in the denosumab and ZA groups are shown in Fig. 2. The cumulative incidences of MRONJ in the denosumab group were significantly higher than those in the ZA group in both cohorts (p = 0.002, Fig. 2a) and in the propensity score–matched cohort (p = 0.017, Fig. 2b).

Cumulative incidence of MRONJ in patients receiving denosumab or ZA for bone metastasis. The cumulative incidences of developing MRONJ were compared between the denosumab and ZA groups (a) before and (b) after propensity score matching of the cohort. MRONJ, medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw; ZA, zoledronic acid

Discussion

This is the first study showing that denosumab treatment can significantly increase the risk of developing MRONJ, when compared to ZA, among patients who received BMA treatment for bone metastasis in a real-world clinical practice setting using a propensity score–matched analysis. Tooth extraction after starting BMA treatment was also a significant risk factor. The incidences of MRONJ in the present study were 9.6% and 4.8% in the denosumab and ZA groups, respectively. The reported incidence of MRONJ is 1–17% [25, 27, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], and the incidences of MRONJ in our study were within this range for both groups. In a combined analysis of three phase III randomized control trials, the incidences of MRONJ were low in patients receiving both denosumab (1.8%; n = 52/2862) and ZA (1.3%; n = 37/2861) [25]. Another randomized control trial also reported that the incidences of MRONJ were low in patients with multiple myeloma receiving both denosumab (4.1%; n = 35/850) and ZA (2.8%; n = 24/852) [37]. In contrast, in retrospective observational studies, the reported incidences of MRONJ were found to vary from 2 to 17% [29,30,31, 38,39,40,41,42] and were relatively higher than those in randomized controlled trials. In randomized controlled trials, the study protocol specified that all participants underwent scheduled periodic dental examinations (e.g., at baseline and every 6 months thereafter) [25, 27, 32,33,34, 36, 37]. On the other hand, in the real-word clinical practice setting used in our study, although all subjects underwent dental examination before the initiation of BMA treatment, the vast majority of them did not receive scheduled periodic dental examinations after the initiation of BMA treatment. If the patients complained of dental symptoms, the attending physicians consulted the dentists. Because scheduled dental examination can reduce the risk of developing MRONJ [17,18,19, 31, 35, 41,42,43], this discordance between randomized control trials and observational studies in real-world clinical practice might affect the risk of MRONJ.

This study revealed via multivariate analysis that denosumab treatment was associated with a significantly higher risk of developing MRONJ than ZA treatment. Moreover, this result was also clearly confirmed by propensity score–matched analysis. The higher risk for developing MRONJ with denosumab than with ZA was consistent with some previous real-world data [40,41,42,43]. Previous randomized controlled trials reported that the incidence of MRONJ in patients treated with denosumab was not significantly different from that in patients treated with ZA, although it tended to be higher in the former [25, 27, 32,33,34, 36, 37]. One potential explanation for this discordance might be due to scheduled dental examination, which we discussed previously. However, when investigating the risk of MRONJ in retrospective observational studies, several biases, such as dental examinations before BMA treatments and dental interventions after starting BMA treatments, should be considered. As such, to reduce the potential bias of patient characteristics associated with the development of MRONJ, we limited the study participants to those examined by dentists before starting BMA treatment. In addition, we performed propensity score matching to control for and reduce selection bias in the denosumab and ZA groups. Recent study and the European Task Force on MRONJ pointed out that alveolar bone histological necroses were observed prior to teeth extractions in patients who were treated with BMAs [44, 45]. Although the results of multivariate analysis in our study showed that tooth extraction after the start of BMA treatment as a significant risk factor, it is important to note that it is highly possible that MRONJ have developed before tooth extraction in our study subjects. Unfortunately, we could not obtain data on alveolar bone necroses prior to teeth extractions in our study subjects because they have received dental procedures at dental clinics rather than our hospital. Taken together, we believe that educating patients and routine periodic dental examinations are essential to reduce the risk of developing MRONJ.

The higher incidence of denosumab-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw seems to reflect its superior effect on bone resorption compared to that of ZA [26, 32, 33]. In clinical practice, careful monitoring of developing MRONJ is essential in all patients receiving denosumab and/or ZA, even if the risk of developing MRONJ in this study was significantly lower than those in the denosumab group. Recently, we reported that MRONJ caused by denosumab resolves faster than that caused by ZA [40]. Bacci et al. reported the importance of appropriate dental visits and treatments in reducing the risk of MRONJ [46]. We believe that diagnosing MRONJ at an earlier stage through appropriate monitoring and multidisciplinary collaborative work with healthcare providers is essential for BMA treatment [47].

We also revealed that tooth extraction after starting BMA treatment was significantly increased by multivariate analysis, which was consistent with the findings of previous reports [19, 21, 25]. In contrast, tooth extractions performed before starting BMAs tended to increase the risk of developing MRONJ in this study, although this increase was not significant. Poor oral health status is known to be a significant risk factor [17,18,19,20], and our results likely support the notion that in unavoidable cases, tooth extraction before starting BMAs is a meaningful intervention to reduce the risk of developing MRONJ. However, in this retrospective study, we could not obtain convincing data related to oral health status before starting BMAs. Further studies are required to confirm these results. Since tooth extraction before starting BMAs significantly increased the risk of developing MRONJ in the univariate analysis, early dental consultation should be considered after patients are diagnosed with cancer.

This study has some limitations. First, oral health status, such as periodontal disease and dental caries, was not fully investigated. To reduce the effect of these factors, we limited the study participants to those examined by dentists before starting BMA treatment. Second, we did not evaluate the effect of other risk factors, such as dental prosthesis and tobacco use [17,18,19,20]. Thirdly, we also could not evaluate data on interval between the initiation of BMA treatments and the date when the patients receive dental evaluation. Similarly, detailed information on dental procedures, and how long time has elapsed between dental extractions and the start of bone-modifying agents are important. In this study, however, we could not obtain exact information, because some patients have visited other dental clinics. Despite our best efforts to obtain clinical information, we were not able to collect all of these data within this retrospective study design. However, to our knowledge, these missing data should have similar impacts among the groups. Lastly, since the patients who complained of dental symptoms consulted a dentist following the request of the attending physicians, dental examinations might be performed when patients had developed oral symptoms, and mild cases of MRONJ might have been underdiagnosed. Despite these limitations, this real-world observational study clearly revealed that the risk of developing MRONJ was significantly higher in advanced cancer patients treated with denosumab than in those treated with ZA.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that denosumab significantly increases the risk of developing MRONJ compared to ZA in cancer patients undergoing treatment for bone metastasis. Tooth extraction after starting BMA treatment is also significantly associated with developing MRONJ. Taken together, these patients require close monitoring in a clinical setting.

Availability of data and material

The data underlying this study are contained within the article.

References

Saito G, Ebata T, Ishiwata T, Iwasawa S, Yoshino I, Takiguchi Y, Tatsumi K (2021) Risk factors for skeletal-related events in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with bone-modifying agents. Support Care Cancer 29:4081–4088

von Moos R, Costa L, Gonzalez-Suarez E, Terpos E, Niepel D, Body JJ (2019) Management of bone health in solid tumours: from bisphosphonates to a monoclonal antibody. Cancer Treat Rev 76:57–67

Mollica V, Rizzo A, Rosellini M, Marchetti A, Ricci AD, Cimadamore A et al (2021) Bone targeting agents in patients with metastatic prostate cancer: state of the art. Cancers 13:546

Link H, Diel I, Ohlmann CH, Holtmann L, Kerkmann M; Associations Supportive Care in Oncology (AGSMO), Medical Oncology (AIO), Urological Oncology (AUO), within the German Cancer Society (DKG) and the German Osteooncological Society (DOG) (2020) Guideline adherence in bone-targeted treatment of cancer patients with bone metastases in Germany. Support Care Cancer 28:2175–2184

Coleman R, Body JJ, Aapro M, Hadji P, Herrstedt J, ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2014) Bone health in cancer patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol 25: iii124–137

Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, John T, Grohe C, Majem M et al (2020) Osimertinib in resected EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 383:1711–1723

Coleman RE, Croucher PI, Padhani AR, Clézardin P, Chow E, Fallon M et al (2020) Bone metastases Nat Rev Dis Primers 6:83

Herbst RS, Giaccone G, de Marinis F, Reinmuth N, Vergnenegre A, Barrios CH et al (2020) Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of PD-L1-selected patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med 383:1328–1339

Fizazi K, Shore N, Tammela TL, Ulys A, Vjaters E, Polyakov S et al (2020) Nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer and survival with darolutamide. N Engl J Med 383:1040–1049

Coleman R, Finkelstein DM, Barrios C, Martin M, Iwata H, Hegg R et al (2020) Adjuvant denosumab in early breast cancer (D-CARE): an international, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 21:60–72

Armstrong AJ, Al-Adhami M, Lin P, Parli T, Sugg J, Steinberg J et al (2020) Association between new unconfirmed bone lesions and outcomes in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with enzalutamide: secondary analysis of the PREVAIL and AFFIRM randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncol 6:217–225

Ng TL, Tu MM, Ibrahim MFK, Basulaiman B, McGee SF, Srikanthan A et al (2020) Long-term impact of bone-modifying agents for the treatment of bone metastases: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 29:925–943

Green JR, Müller K, Jaeggi KA (1994) Preclinical pharmacology of CGP 42’446, a new, potent, heterocyclic bisphosphonate compound. J Bone Miner Res 9:745–751

Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S et al (1998) Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:3597–3602

Ikesue H, Tsuji T, Hata K, Watanabe H, Mishima K, Uchida M et al (2014) Time course of calcium concentrations and risk factors for hypocalcemia in patients receiving denosumab for the treatment of bone metastases from cancer. Ann Pharmacother 48:1159–1165

Marx RE (2003) Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61:1115–1117

Yarom N, Shapiro CL, Peterson DE, Van Poznak CH, Bohlke K, Ruggiero SL et al (2019) Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: MASCC/ISOO/ASCO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 37:2270–2290

Yoneda T, Hagino H, Sugimoto T, Ohta H, Takahashi S, Soen S et al (2017) Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Position Paper 2017 of the Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. J Bone Miner Metab 35:6–19

Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, Felsenberg D, McCauley LK, O’Ryan F et al (2015) Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: a systematic review and international consensus. J Bone Miner Res 30:3–23

Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B et al (2014) American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw–2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72:1938–1956

Okuma S, Matsuda Y, Nariai Y, Karino M, Suzuki R, Kanno TA (2020) A retrospective observational study of risk factors for denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with bone metastases from solid cancers. Cancers 12:1209

Drudge-Coates L, Van den Wyngaert T, Schiødt M, van Muilekom HAM, Demonty G, Otto S (2020) Preventing, identifying, and managing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a practical guide for nurses and other allied healthcare professionals. Support Care Cancer 28:4019–4029

Limones A, Sáez-Alcaide LM, Díaz-Parreño SA, Helm A, Bornstein MM, Molinero-Mourelle P (2020) Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) in cancer patients treated with denosumab vs. zoledronic acid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 25:e326–e336

Chen F, Pu F (2016) Safety of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in patients with bone metastases: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncol Res Treat 39:453–459

Saad F, Brown JE, Van Poznak C, Ibrahim T, Stemmer SM, Stopeck AT et al (2012) Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann Oncol 23:1341–1347

Lipton A, Fizazi K, Stopeck AT, Henry DH, Brown JE, Yardley DA et al (2012) Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer 48:3082–3092

Van den Wyngaert T, Wouters K, Huizing MT, Vermorken JB (2011) RANK ligand inhibition in bone metastatic cancer and risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ): non bis in idem? Support Care Cancer 19:2035–2040

Colella G, Campisi G, Fusco V (2009) American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper: Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws-2009 update: the need to refine the BRONJ definition. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 67:2698–2699

Jadu F, Lee L, Pharoah M, Reece D, Wang L (2007) A retrospective study assessing the incidence, risk factors and comorbidities of pamidronate-related necrosis of the jaws in multiple myeloma patients. Ann Oncol 18:2015–2019

Cafro AM, Barbarano L, Nosari AM, D’Avanzo G, Nichelatti M, Bibas MO (2008) Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma treated with bisphosphonates: definition and management of the risk related to zoledronic acid. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 8:111–116

Ripamonti CI, Maniezzo M, Campa T, Fagnoni E, Brunelli C, Saibene G et al (2009) Decreased occurrence of osteonecrosis of the jaw after implementation of dental preventive measures in solid tumour patients with bone metastases treated with bisphosphonates. The experience of the National Cancer Institute of Milan. Ann Oncol 20:137–145

Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ, Steger GG, Tonkin K, de Boer RH et al (2010) Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol 28:5132–5139

Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, Damiao R, Brown J, Karsh L et al (2011) Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 377:813–822

Henry DH, Costa L, Goldwasser F, Hirsh V, Hungria V, Prausova J et al (2011) Randomized, double-blind study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced cancer (excluding breast and prostate cancer) or multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 29:1125–1132

Kajizono M, Sada H, Sugiura Y, Soga Y, Kitamura Y, Matsuoka J et al (2015) Incidence and risk factors of osteonecrosis of the jaw in advanced cancer patients after treatment with zoledronic acid or denosumab: a retrospective cohort study. Biol Pharm Bull 38:1850–1855

Stopeck AT, Fizazi K, Body JJ, Brown JE, Carducci M, Diel I et al (2016) Safety of long-term denosumab therapy: results from the open label extension phase of two phase 3 studies in patients with metastatic breast and prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 24:447–455

Raje N, Terpos E, Willenbacher W, Shimizu K, Garcia-Sanz R, Durie B et al (2018) Denosumab versus zoledronic acid in bone disease treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an international, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 19:370–381

Guillot A, Joly C, Barthelemy P, Meriaux E, Negrier S, Pouessel D et al (2019) Denosumab toxicity when combined with anti-angiogenic therapies on patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a GETUG study. Clin Genitourin Cancer 17:e38–e43

Soares AL, Simon S, Gebrim LH, Nazario ACP, Lazaretti-Castro M (2020) Prevalence and risk factors of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in osteoporotic and breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 28:2265–2271

Ikesue H, Mouri M, Tomita H, Hirabatake M, Ikemura M, Muroi N, Yamamoto S, Takenobu T, Tomii K, Kawakita M, Katoh H, Ishikawa T, Yasui H, Hashida T (2021) Associated characteristics and treatment outcomes of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients receiving denosumab or zoledronic acid for bone metastases. Support Care Cancer 29:4763–4772

Nakai Y, Kanaki T, Yamamoto A, Tanaka R, Yamamoto Y, Nagahara A et al (2020) Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis treated with bone-modifying agents. J Bone Miner Metab 39:295–301

Hallmer F, Bjarnadottir O, Gotrick B, Malmstrom P, Andersson G (2020) Incidence of and risk factors for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in women with breast cancer with bone metastasis: a population-based study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 130:252–257

Owosho AA, Liang STY, Sax AZ, Wu K, Yom SK, Huryn JM et al (2018) Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: an update on the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center experience and the role of premedication dental evaluation in prevention. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 125:440–445

Nicolatou-Galitis O, Papadopoulou E, Vardas E, Kouri M, Galiti D, Galitis E et al (2020) Alveolar bone histological necrosis observed prior to extractions in patients, who received bone-targeting agents. Oral Dis 26:955–966

Schiodt M, Otto S, Fedele S, Bedogni A, Nicolatou-Galitis O, Guggenberger R et al (2019) Workshop of European Task Force on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw-current challenges. Oral Dis 25:1815–1821

Bacci C, Cerrato A, Bardhi E, Frigo AC, Djaballah SA, Sivolella SA (2021) Retrospective study on the incidence of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) associated with different preventive dental care modalities. Support Care Cancer https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06587-x [online ahead of print]

Boquete-Castro A, Gómez-Moreno G, Calvo-Guirado JL, Aguilar-Salvatierra A, Delgado-Ruiz RA (2016) Denosumab and osteonecrosis of the jaw. A systematic analysis of events reported in clinical trials. Clin Oral Implants Res 27:367–375

Funding

This study was partly supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (grant number: JP18K06770).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Hiroaki Ikesue, Kohei Doi, Mayu Morimoto, Masaki Hirabatake, Toshihiko Takenobu, and Tohru Hashida; methodology: Hiroaki Ikesue, Masaki Hirabatake, and Shinsuke Yamamoto; validation: Kohei Doi and Mayu Morimoto; formal analysis: Hiroaki Ikesue; investigation: Hiroaki Ikesue, Kohei Doi, Mayu Morimoto, and Shinsuke Yamamoto; writing—original draft preparation: Hiroaki Ikesue; writing—review and editing: Hiroaki Ikesue, Kohei Doi, Mayu Morimoto, Masaki Hirabatake, Nobuyuki Muroi, Shinsuke Yamamoto, Toshihiko Takenobu, and Tohru Hashida; funding acquisition: Hiroaki Ikesue. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (approval number: k191010). Due to the retrospective nature of this work, the research plan was published on the homepage of the hospital according to the instructions of the Ethics Committee in accordance with the guaranteed opt-out opportunity.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ikesue, H., Doi, K., Morimoto, M. et al. Risk evaluation of denosumab and zoledronic acid for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with bone metastases: a propensity score–matched analysis. Support Care Cancer 30, 2341–2348 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06634-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06634-7