Abstract

Purpose

Providing high-quality care for the dying is essential in palliative care. Quality of care can be checked, compared, and improved by assessing responses from bereaved next-of-kin. The objectives of this study are to examine quality of care in the last 2 days of life of hospitalized patients considering specific aspects of their place of care.

Methods

The “Care of the Dying Evaluation” (CODE™) questionnaire, validated in German in 2018 (CODE-GER), examines quality of care for the patient and support of next-of-kin, allocating values between 0 (low quality) and 4 (high quality). The total score (0–104) is divided into subscales which indicate support/time given by doctors/nurses, spiritual/emotional support, information/decision-making, environment, information about the dying process, symptoms, and support at the actual time of death/afterwards. Next-of-kin of patients with an expected death in specialized palliative care units and other wards in two university hospitals between April 2016 and March 2017 were included.

Results

Most of the 237 analyzed CODE-GER questionnaires were completed by the patient’s spouse (42.6%) or children (40.5%) and 64.1% were female. Patients stayed in hospital for an average of 13.7 days (3–276; SD 21.1). Half of the patients died in a specialized palliative care unit (50.6%). The CODE-GER total score was 85.7 (SD 14.17; 25–104). Subscales were rated significantly better for palliative care units than for other wards. Unsatisfying outcomes were reported in both groups in the subscales for information/decision-making and information about the dying process.

Conclusion

The overall quality of care for the dying was rated to be good. Improvements of information about the dying process and decision-making are needed.

Trial registration

DRKS00013916

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quality is a central aspect of end-of-life care at home and in an institutional setting; it should therefore be measured to ensure best services and support in the long term. The majority of patients want to spend their last phase of life at home [1,2,3,4,5], but despite this a high proportion of deaths occur in hospitals in most Western European countries [6, 7]—including Germany [8]. As such, death in hospital is a common occurrence and dying patients are treated in almost all hospital settings. The density of specialized palliative care services in hospitals differs among Western European countries [3, 9]. In institutions where such services are available, patients with complex needs receive additional support from specialized hospital support teams or are transferred to a palliative care unit (PCU). In a PCU, death is a frequent and often predictable event [10]. In curative settings, death might be perceived as an unwanted event, which may affect the care of patients and next-of-kin.

Quality of end-of-life care can be measured by assessing responses from informal carers or health professionals [11, 12]. In palliative care, next-of-kin are perceived as a “unit of care” along with the patient [13]. Consequently, next-of-kin may be able to share valuable information about their perception of the quality of care. Several studies on outcomes for the care of the dying have been published, including an assessment of the next-of-kin’s satisfaction with palliative care services [14,15,16], quality of care [17, 18], patients’ symptom distress [19], and quality estimation of the dying process [12, 20]. A systematic review of psychometric properties of tools measuring quality of death, dying, and care was recently published [21]. Currently, only two instruments for assessing end-of-life care exist in German. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire – German Version (QoDD-D) [11, 12] examines quality of life and considers the circumstances of dying. Care of the Dying Evaluation (CODE™) is based on the “Evaluating Care and Health Outcomes – for the Dying” (ECHO-D) [18] and—unlike the QoDD-D—aims at assessing quality of care and support for next-of-kin corresponding to the concept of palliative care in hospitals. It has recently been validated in German (CODE-GER) by the authors’ working group (validation manuscript in review process, reference will be added).

Research question

The dataset that was originally collected and prepared for the validation study of the CODE-GER was used to perform a secondary analysis on (i) the quality of care for the dying assessed by next-of-kin of patients who died on different wards of two German hospitals and (ii) the differences and similarities in quality of care between patient groups according to place of care.

Methods

Participating next-of-kin were defined as loved ones, relatives, friends, or other proxies who were in close contact/relationship with the patient and personally visited the patient in hospital in his/her last 2 days of life. This study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00013916, https://www.drks.de) and is reported according to the STROBE Reporting Guideline [22].

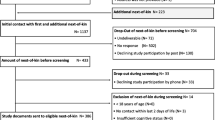

Between April 2016 and March 2017, 1714 deaths occurred on participating wards (internal, neurological, and palliative medicine) in two study centers (Mainz, Erlangen; Germany). Deceased patients were included if they were at least 18 years of age and had stayed in the hospital ward where they died for at least 3 days, death was expected based on the physician’s judgment, and the cause of death was not sudden in nature (validation manuscript in review process, reference will be added). Data necessary to screen for inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as contact addresses of bereaved next-of-kin were extracted through a hospital information system report, from the patient records, and proceeded by the centers research team in accordance with procedures in the participating wards and data protection regulations.

For participation of next-of-kin, an opt-in strategy was used. Following the advice by data protection supervisors, next-of-kin were approached via postcard and in responding actively gave their consent to be contacted for study purposes. The consortium members carefully decided on the time of contact to bereaved next-of-kin, based on experience from previous studies [23]. A data custodian handled the dispatch and return, so that the data from the pseudonymized questionnaires could not be associated with patients by the scientists. No incentives were provided for participation.

After applying the inclusion criteria, the next-of-kin of 914 patients were invited by mail from the center’s researchers 8 to 16 weeks after the patients’ death. A repeat invitation to participate in the study was sent 4 weeks later if a reply had not been received. To assure an inter-rater population during the validation study, additional other next-of-kin (n = 223) that had been proposed nominated by participating next-of-kin were contacted. Overall 1137 next-of-kin were contacted, out of which 563 (49.5%) responded to the invitation; n = 130 declined participation, and n = 433 consented to telephone contact for further information.

During the telephone call, a further 14 next-of-kin were excluded due to insufficient language knowledge (n = 1), lack of contact to the patient at hospital in the last 2 days of life (n = 3), or self-reported emotional distress (n = 10). Another 33 declined due to personal reasons. The remaining consenting next-of-kin (n = 386) received the study material by mail. They were contacted by telephone to make sure the study material had been received and to provide support if they had not returned the study material 3 to 4 weeks after initial dispatch. In total, 317 participants (82.1%) returned a completed CODE questionnaire. The final response rate of contacted next-of-kin was 27.9% (317/1137). Six questionnaires were excluded due to missing informed consent statements; a further 26 questionnaires were excluded due to high rates of missing data (> 15%). For the present analysis, a further 48 questionnaires were excluded as they originated from inter-rater participants which was only relevant for the validation study. In total, n = 237 questionnaires were included in the present analysis.

CODE questionnaire

The CODE-GER study examined 7 subscales including 26 items (see Table 2) through principal component analysis. The study demonstrated good psychometric properties: internal consistency, α = 0.86; inter-rater reliability, ICC (1,1) = 0.79; and retest reliability, ICC (2,1) = 0.85. The rating scales differed between questions from binary scales up to 5-point Likert scales (see Table 2 for details), with possible values between 0 and 4.

For each subscale, scores of the included items were added to a subscale score, which in turn were summed up to the total score (0 to 104); higher values indicate a higher quality of care.

Two items from the original CODE questionnaire (addressing “cleanliness of the ward area” and “right place for the patient to die”) were not included and are maintained as optional items in CODE-GER. The “right place for the patient to die” item is reported here as an overall item.

Two further questions assess overall impressions of end-of-life care: an estimation of the amount of time that the patient was treated with respect and dignity, and to what extent the next-of-kin felt adequately supported during the last 2 days of the patient’s life. One overall question examines the respondents’ willingness to recommend the ward to friends or family and was reintroduced from an older version of CODE™.

Socio-demographic data on the participant and the patient, and further health/disease-related information on the patient were provided by next-of-kin in the questionnaire.

Space for free text allowed the respondents to give feedback on particular items and the entire questionnaire. If participants provided reasons within the free texts for ticking “do not know” or leaving out the answer to a question, these explanations were included in the “Results” section. The same free texts were included in the “Results” section to aid the interpretation of perceived low quality of care aspects and analyze the potential for improvement.

Data preparation and analysis

Missing values were imputed via expectation–maximization for interval variables and the modus score of corresponding items for categorical variables; a proportion of up to 15% missing items was tolerated. The authors decided on the 15% threshold according to the missing patterns of the dataset and to similar questionnaires such as the QoDD-D [11, 12], considering the risk of bias due to imputation and the number of questionnaires excluded. Questionnaires with higher missing rates were excluded from analysis. Missing rates are presented for transparency reasons (see Table 2). Missing data of overall items were not imputed. Descriptive statistics were calculated, including mean values and standard deviation (SD) within subscales, frequencies of single items, and missing values.

Group comparisons for quality of care are presented for patients who died at a PCU and patients who died at other wards. T tests were used to compare the mean subscale scores and sum score of subscales (total score) for the groups.

Results were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Multiple linear regressions were used to find out if group differences were predicted by other variables than place of death.

The analysis was performed using the statistics software SPSS 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) developed by IBM [24].

Free texts were analyzed based on the qualitative content analysis approach by Mayring [25] and using the MAXQDA software for qualitative analysis [26].

Results

Study population

Patients

Half of the deceased patients were between 60 and 79 years old (51.5%) and 50.6% were male. 2.5% of patients were not of German nationality (nationality not stated by 3% of participants). The average length of stay was 13.7 days (range 3–276, SD 21.1). Cancer diagnosis was stated for 56.5% of patients. Half of the patients died in a specialized PCU (50.6%). Those who died at another ward (49.4%) were hospitalized on a normal ward (n = 60) or an intensive care unit (n = 57).

Next-of-kin

Most participants were between 50 and 69 years old (52.7%). 64.6% of respondents were female. Few respondents (2.0%) stated other nationalities than German (nationality not stated by 8.1% of participants). Most of the participants were patients’ spouses (42.6%) or children (40.5%). Others (16.9%) were parents, siblings, grandchildren, friends, or neighbors.

Respondents returned the CODE questionnaire after an average of 124 days (68–354 days, median 114 days) after the patient’s death.

Quality of care—total score and comparing subscales

The mean CODE-GER total score was 85.7 (range 25–104, SD 14.17). Only 9 questionnaires (3.8%) scored less than 50% of the total score. The mean scores of the subscales and the percentage of their maximum values are presented to enable comparisons between subscales (Table 1). The subscales “information about dying process,” “symptom presence,” and “information and decision-making” showed the lowest mean values (70.5, 70.8, 71.9); the subscales “support and time doctors and nurses” and “support at actual time of death and afterwards” (91.1, 91.8) were rated highest. All subscales have negative skewness values, showing that the distribution is left-skewed and not normally distributed. Participants tend to estimate the quality better than a normal distribution would suggest.

Frequencies of answers give a more detailed insight into the measured quality of care subscales (see Fig. 1). The highest values (3–4) were most often reached in subscale 7 “support at actual time of death and afterwards.”

For the subscales “information about dying process,” “information and decision-making,” and “symptom presence,” up to 29.5% of respondents rated lower values (0–1), thus indicating aspects of care in need of improvement (see Fig. 1). The frequencies of answers to the single items are shown in Table 2.

Almost half of the participants (45.6%) stated that they had not been told what to expect when the patient was dying, whereas 52.9% of those participants thought information would have been helpful (29.0% out of 237). Free text answers reflected this sentiment in more detail: Next-of-kin reported how and when the information was given, if it was useful, and the implications of lacking information on their grief: “Up to this day, I still can’t cope with the last breaths. Didn’t know it was so extreme, even though my father wasn’t conscious“. Contrarily, it was also stated that more information about what to expect would have possibly worsened the situation: “I think that would have made it even harder for me.” Others reported whether they had been informed in time about the pending death of the patient and if they were able to be with the patient in his or her last hours of life. Free text suggests the beneficial nature of providing leaflets on the dying process, the wish to be given information about the dying process in absence of the patient and the request for guidance on impending death. “It would have been helpful for me [...] to remind me in this exceptional situation to bring his favourite music, lyrics or prayers [...].”

Furthermore, next-of-kin reported that they were surprised by the “suddenness of the dying process,” although more than 80% of participants answered that they were told that the patient would die soon.

The information was most frequently given by doctors (81.1%) or nurses (27.2%) and in few cases (n = 4) by others.

43.6% of participants reported that the team did not discuss with them whether hydration would be appropriate in the last 2 days of life, but 26.2% of them would have found such a conversation helpful.

Increased rates of missing values

The patient’s and the next-of-kin’s fulfillment of religious or spiritual needs (10.1% and 10.5% missing) are particularly noteworthy due to increased numbers of missing values (see Table 2).

Reasons for skipping the answer were provided in the free text by statements such as “no religious and spiritual needs of patient or next-of-kin” or “religious and spiritual support of no importance for patient or next-of-kin” or “not belonging to any denomination.”

Overall assessment on quality of care of the dying in hospitals

Participants mainly considered that the hospital is the right place for the patient’s end of life (83.5%). 7.2% thought that it was not the right place and 6.8%/2.5% were unsure/did not know. Most participants (87.8%) would (likely or rather likely) recommend the ward and ten participants stated that they did not know or skipped the answer.

Overall, 87.8% of participants felt adequately supported during the patient’s last 2 days of life. Most participants stated that the patient was treated with respect and dignity by the doctors always/most of the time (86.5%). Nurses were perceived by 92.9% of respondents as treating the patient with dignity.

Comparing quality of care according to place of death

For most subscales and the total score, the quality of care is perceived significantly better by next-of-kin at a PCU than on other wards (see Table 3). Symptom presence was higher for patients at a PCU. The information subscales (3, 5) showed similar values. Next-of-kin of patients on other wards stated that they had not been involved in decisions about treatment and care more often than those from a PCU (14.5%/11.7%). The appropriateness of giving fluids was discussed less frequently on a PCU (42.5%) than on other wards (55.6%); every fifth next-of-kin indicated that a discussion on this issue would have been helpful (PCU 22.5%; other wards: 18.8%). Information that the patient was likely to die soon was missing more frequently on a PCU (17.5%) than on other wards (12%). Almost half of the next-of-kin in both settings stated that the healthcare team did not talk to them about what to expect when the patient was dying (PCU 45.8%; other wards 45.3%). A substantial number of next-of-kin indicated that a discussion about this issue would have been helpful (PCU 33.3%; other wards 23.1%).

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted for the variables patient’s age (> 60 years vs. < 60 years) and gender, cancer diagnosis, next-of-kin’s age (> 60 years vs. < 60 years) and gender, and relationship to patient (partner vs. others; child vs. others) to identify the best fitting model. The statistically significant model (F(6,230) = 2.180, p = 0.046) included the variables place of death, cancer diagnosis, relationship to patient (partner vs. others; child vs. others), next-of-kin’s gender, and patient’s age (> 60 years vs. < 60 years). The adjusted R2 indicated that 2.9% of the variance in the total sum score can be explained by variances in the predictor variables. The analysis suggested that place of death (ß = 0.167) was the most influential predictor of the total sum score and next-of-kin’s gender (ß = 0.065) was the least influential predictor of the total sum score in the model.

Place of death was shown to be a statistically relevant predictor of the total sum score (t = 2.334, p = 0.020). Being the patient’s child (t = 1.282, p = 0.201), patient’s age (t = 1.392, p = 0.165), being the patient’s partner (t = 0.828, p = 0.408), cancer diagnosis (t = − 0.980, p = 0.328), and next-of-kin’s gender (t = 1.011, p = 0.313) were not statistically relevant predictors of the total sum score (see supplementary Table 1).

Models using the subscale sum scores as criterion variable showed the place of death to be a statistically significant predictor of the scores of subscales 1, 2, 4, and 7 considering other variables. The symptom presence subscale model 6 (see supplementary Table 1) indicated cancer diagnosis to be a statistically significant predictor of the subscale sum score. Place of death was not found to be a statistically significant predictor (see supplementary Table 1). The PCUs in this study had a much higher proportion of patients with cancer diagnosis (76%) than other wards (37%). The findings indicate an effect of cancer diagnosis on symptom presence rather than the place of death.

The majority of next-of-kin reported good general quality of care; however, differences between PCUs and other wards were found (see Table 4).

Discussion

Quality is estimated to be high by the vast majority0 of next-of-kin with few negative exceptions comparable with the results of the original CODE validation study in the UK [27] and others [28]. Subsample comparisons showed higher total scores for PCU patients, even considering other variables. This pattern was the same for the overall impressions. The sensibility for end-of-life care aspects might be higher at PCUs with a holistic quality-of-life approach [29] and training. Environmental and staff-related factors, therapy goals, and expectations of the next-of-kin might differ according to the ward the patient was admitted to, and these factors may change during disease progression. Also, scarce personnel and time resources of other wards could have an impact. Differences in symptom presence showed to be influenced by diagnosis rather than place of death. Next-of-kin of PCU patients rated quality of care significantly higher, except for the subscales relating to information. Notably, improvements are necessary in information and decision-making irrespective of the type of ward. Surprisingly enough, the answers by a substantial part of next-of-kin of patients who died at a PCU indicate information deficits in important aspects, specifically the appropriateness of administering intravenous fluids and the circumstances of the dying process. Despite the inclusion criteria of expected death and 80% of participants who confirmed that they were told that the patient would die soon, free text answers showed that some next-of-kin were surprised by the patient’s death and felt unprepared. Findings from international e.g. qualitative studies that aimed to investigate the family members’ perspectives on dying in hospitals [30, 31] showed similar results. International studies using outcome instruments to measure the quality of care for the dying explicitly in hospital settings in other countries [1, 27, 32] also identified next-of-kin’s perception of deficits in providing information by health professionals and the inclusion in decision-making as well as difficult symptom control. Issues concerning information provision and decision-making are of paramount importance in order to meet patient’s and next-of-kin needs in an appropriate manner. Whereas our study reveals in this regard during the last 2 days of end-of-life care, it is not intended to question staff members’ communication abilities in general. Next-of-kin are in an exceptional situation with a beloved one dying and the transfer of information in these situations might be hampered [33,34,35]. Previous research on information provision by Verkissen et al. (2019) found a lower percentage (10.7–13.2%) of relatives reporting suboptimal information provision in palliative care settings in Belgium [36] but referred to experiences to the whole length of palliative care guidance. A literature review by Belanger (2011) showed challenges to shared decision-making in palliative care due to delayed decisions and seldom discussion of other treatment options [37]. However, the decision-making experiences refer to the full length of the care trajectory and not the last 2 days as in this study. One major implication for clinical care should therefore be raising sensitivity of PCU staff to the importance of repeated communication on dying who might have become accustomed to the circumstances of the dying process. The respondents’ free text answers in the current study provided additional valuable insights into beneficial interventions such as offering leaflets on the dying process, providing information about the dying process to next-of-kin in absence of the patient, and providing information on arranging the farewell. Information leaflets [38] and conversations should be tailored to next-of-kin needs, comprehension level, and emotional state;, should contain non-medical information as well; and should be offered repeatedly. Better comprehensibility of leaflets could be achieved by patient and public involvement in the design of information material. An important measure—as carried out at the two study site hospitals after receiving the results—should be to involve the hospital quality management and to initiate a process of implementing specific guidelines for care of the dying.

Future research should address communication models and instruments that help to overcome difficulties in information transfer and focus on the content and form of information provided to next-of-kin facing their loved ones dying.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The major strength of this analysis are the broad insights gained into the under-researched aspect of the quality of care of dying patients in hospitals examining the questionnaires’ subscales, items, and free text answers. Group comparisons have demonstrated the differences and similarities between specialized PCUs and other wards and have helped to identify gaps in the care of the dying in hospital and the next-of-kins’ support. The multiple regression analysis ensures that the differences are not linked to other factors such as patients’ or respondents’ characteristics.

A methodological limitation may be inherent to the opt-in procedure, as primarily next-of-kin that were exceptionally pleased with quality of care or rather dissatisfied may have been more motivated to participate implying a selection bias.

Both study centers are university hospitals and the results are not directly transferable to all hospitals.

The group comparisons did not differentiate between patients on other wards with and without hospital palliative care support teams or between intensive care and acute care.

Although next-of-kin are the preferred sources of patient-centered information as the patient cannot be asked anymore, estimations may be biased by their emotions; thus, selective perception can affect the memorization and the later recall of memory.

Higher missing rates for the emotional and spiritual support items compared with other subscales, for both patients and next-of-kin and irrespective of the type of ward could be inherent in the pluralism of the definition [39] of spirituality.

Findings on quality of care for the dying using the CODE-GER can be utilized to identify gaps in the quality of care, design strategies for improvement, and allow benchmarking between different institutions and settings. Nevertheless, improvement strategies should consider the different therapy aims, specializations, personnel, and financial resources of the settings. The differentiation between quality of care and support for next-of-kin according to the palliative care approach allows measuring outcome and improving both aspects, if needed.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that analyzing CODE-GER contents gives valuable insights into the quality of care during the dying phase in hospitalized patients and identified specific aspects in need of improvement. This can facilitate further quality management and benchmarking initiatives within the hospital and also between institutions.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

28 May 2020

The surname and name of Christoph (name) Ostgathe (surname) are reversed.

References

Augustussen M, Hounsgaard L, Pedersen ML, Sjogren P, Timm H (2017) Relatives’ level of satisfaction with advanced cancer care in Greenland - a mixed methods study. Int J Circumpolar Health 76(1):1335148. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2017.1335148

Calanzani N, Moens K, Cohen J, Higginson IJ, Harding R, Deliens L, Toscani F, Ferreira PL, Bausewein C, Daveson BA, Gysels M, Ceulemans L, Gomes B, Project P (2014) Choosing care homes as the least preferred place to die: a cross-national survey of public preferences in seven European countries. BMC Palliat Care 13:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-13-48

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin (DGP), Deutscher Hospiz- und PalliativVerband (DHPV) (2015) Palliativversorgung im Krankenhaus Gemeinsame Stellungnahme der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin (DGP) und des Deutschen Hospiz- und PalliativVerbandes (DHPV) zum Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung für ein Hospiz- und Palliativgesetz (HPG). https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/images/stories/Stellungnahme_DGP_DHPV_HPG_02092015.pdf. Accessed 10 Sept 2019

Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N, Cohen J, Deliens L, Daveson BA, Bechinger-English D, Bausewein C, Ferreira PL, Toscani F, Meñaca A, Gysels M, Ceulemans L, Simon ST, Pasman HRW, Albers G, Hall S, Murtagh FEM, Haugen DF, Downing J, Koffman J, Pettenati F, Finetti S, Antunes B, Harding R, on behalf of P (2012) Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol 23(8):2006–2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr602

Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ (2000) Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med 3(3):287–300. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287

Cohen J, Pivodic L, Miccinesi G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Naylor WA, Wilson DM, Loucka M, Csikos A, Pardon K, Van den Block L, Ruiz-Ramos M, Cardenas-Turanzas M, Rhee Y, Aubry R, Hunt K, Teno J, Houttekier D, Deliens L (2015) International study of the place of death of people with cancer: a population-level comparison of 14 countries across 4 continents using death certificate data. Br J Cancer 113:1397–1404. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.312 https://www.nature.com/articles/bjc2015312#supplementary-information. Accessed 20 Oct 2015

Davies E, Higginson IJ (2004) Palliative care. The Solid Facts. World Health Organization, Denmark

Bundesamt für Statistik (2017) Gesundheit. Diagnosedaten der Patienten und Patientinnen in Krankenhäusern (einschl. Sterbe- und Stundenfälle) 2016. Fachserie 12 Reihe 6.2.1. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Krankenhaeuser/Publikationen/Downloads-Krankenhaeuser/diagnosedatenkrankenhaus-2120621167004.pdf;jsessionid=5EF036BE3F2F306AF5786EA8B2A69D52.internet8711?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 27 April 2020

Centeno C, Lynch T, Donea O, Rocafort J, Clark D (2013) EAPC atlas of palliative care in Europe 2013, Full edn. EAPC Press, Milan

Hospiz- und Palliativ-Erfassung (HOPE) (2016) CLARA Klinische Forschung Clinical analysis, research and application Hospiz-undPalliativ-Erfassung Tabellen 2016. https://www.hope-clara.de/download/2016_HOPE_Tabellen.pdf. Accessed 22 March 2017

Heckel M, Bussmann S, Stiel S, Ostgathe C, Weber M (2016) Validation of the German version of the Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire for Health Professionals. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 33(8):760–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115606075

Heckel M, Bussmann S, Stiel S, Weber M, Ostgathe C (2015) Validation of the German version of the Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire for Informal Caregivers (QODD-D-Ang). J Pain Symptom Manag 50(3):402–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.03.020

Faull C (2012) The context and principles of palliative care. In: Christina F, Sharon dC, Alex N, Fraser B (eds) Handbook of palliative care, 3rd edn. JohnWiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, pp 1–14

Aoun S, Bird S, Kristjanson LJ, Currow D (2010) Reliability testing of the FAMCARE-2 scale: measuring family carer satisfaction with palliative care. Palliat Med 24(7):674–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216310373166

Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S (2003) Measuring quality of palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE Scale. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehab 12(2):167–176

Morita T, Chihara S, Kashiwagi T, Quality Audit Committee of the Japanese Association of H, Palliative Care U (2002) A scale to measure satisfaction of bereaved family receiving inpatient palliative care. Palliat Med 16(2):141–150. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216302pm514oa

Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, Edgman-Levitan S, Fowler J (2001) Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manag 22(3):752–758

Mayland CR, Lees C, Germain A, Jack BA, Cox TF, Mason SR, West A, Ellershaw JE (2014) Caring for those who die at home: the use and validation of ‘Care Of the Dying Evaluation’ (CODE) with bereaved relatives. BMJ Support Palliat Care 4(2):167–174. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000596

Hickman SE, Tilden VP, Tolle SW (2001) Family reports of dying patients’ distress: the adaptation of a research tool to assess global symptom distress in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manag 22(1):565–574

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I (2002) A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manag 24(1):17–31

Kupeli N, Candy B, Tamura-Rose G, Schofield G, Webber N, Hicks SE, Floyd T, Vivat B, Sampson EL, Stone P, Aspden T (2019) Tools measuring quality of death, dying, and care, completed after death: systematic review of psychometric properties. Patient 12(2):183–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0328-2

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S (2014) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 12(12):1495–1499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013

Stiel S, Heckel M, Bussmann S, Weber M, Ostgathe C (2015) End-of-life care research with bereaved informal caregivers--analysis of recruitment strategy and participation rate from a multi-centre validation study. BMC Palliat Care 14:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-015-0020-4

IBM Corp (2013) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY

Maryring P (1991) Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In: Flick U, von Kardorff E, Heiner K, von Rosenstiel L, Wolff S (eds) Handbuch qualitative Forschung: Grundlagen, Konzepte, Methoden und Anwendungen. Beltz - Psychologie Verl. Union, München

VERBI Software. Consult. Sozialforschung GmbH (1989-2015) MAXQDA, software for qualitative data analysis, 1989 – 2015, VERBI Software. Consult. Sozialforschung GmbH, Berlin, Deutschland

Mayland CR, Mulholland H, Gambles M, Ellershaw J, Stewart K (2017) How well do we currently care for our dying patients in acute hospitals: the views of the bereaved relatives? BMJ Support Palliat Care:bmjspcare-2014-000810. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000810

Mayland C, McGlinchey T, Gambles M, Mulholland H, Ellershaw J (2018) Quality assurance for care of the dying: engaging with clinical services to facilitate a regional cross-sectional survey of bereaved relatives’ views. BMC Health Serv Res 18(1):761. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3558-z

World Health Organization (2002) WHO Definition of Palliative Care. World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed 1.3.2017 2017

Dunne K, Sullivan K (2000) Family experiences of palliative care in the acute hospital setting. Int J Palliat Nurs 6(4):170–178. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2000.6.4.8930

Dose AM, Carey EC, Rhudy LM, Chiu Y, Frimannsdottir K, Ottenberg AL, Koenig BA (2015) Dying in the hospital: perspectives of family members. J Palliat Care 31(1):13–20

Johnsen AT, Ross L, Petersen MA, Lund L, Groenvold M (2012) The relatives’ perspective on advanced cancer care in Denmark. A cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer 20(12):3179–3188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1454-3

Payne S (2010) White paper on improving support for family carers in palliative care: part 1: recommendations from the European association for palliative care (EAPC) task force on family carers. Eur J Palliat Care 17(5):238–245

Hudson PL, Aranda S, Kristjanson LJ (2004) Meeting the supportive needs of family caregivers in palliative care: challenges for health professionals. J Palliat Med 7(1):19–25. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662104322737214

Harris KA (1998) The informational needs of patients with cancer and their families. Cancer Pract 6(1):39–46

Verkissen MN, Leemans K, Van den Block L, Deliens L, Cohen J (2019) Information provision as evaluated by people with cancer and bereaved relatives: a cross-sectional survey of 34 specialist palliative care teams. Patient Educ Couns 102(4):768–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.11.012

Belanger E, Rodriguez C, Groleau D (2011) Shared decision-making in palliative care: a systematic mixed studies review using narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 25(3):242–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216310389348

Tomlinson K, Barker S, Soden K (2012) What are cancer patients’ experiences and preferences for the provision of written information in the palliative care setting? A focus group study. Palliat Med 26(5):760–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311419988

Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C (2010) Review: the understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med 24(8):753–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216310375860

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank all next-of-kin for their participation. We thank the medical directors at the two study centers and the responsible physicians for their support. We thank the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool for the provision of CODE™ and its user guide.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. This project has received funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) WE 561312-1 and STI 6942-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. took part in the development of the study design, organized the study in Erlangen, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. A.R.V. organized the study in Mainz, analyzed the data, and contributed to the manuscript draft. S.S. co-wrote the grant application and developed the study design. S.G. organized the study in Mainz. J.R. supported the analysis of group comparisons. S.K. was responsible for analyzing free text answers. C.O. developed the study design. M.W. wrote the grant application and developed the study design. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Research ethics and patient consent

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of both study centers: Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg 112 14 Bc (14.4.2014); Landesärztekammer Rheinland-Pfalz 837.331.13 (901 6-F) (5.2.2016). Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Research team members and data custodian were hospital employees and authorized under the German data protection laws.

Disclaimer

The funding source was not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised. The name of Christoph Ostgathe was incorrectly captured.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 16.2 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heckel, M., Vogt, A.R., Stiel, S. et al. The quality of care of the dying in hospital—next-of-kin perspectives. Support Care Cancer 28, 4527–4537 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05465-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05465-2