Abstract

Purpose

Trials of novel drugs used in advanced disease often show only progression-free survival or modest overall survival benefits. Hypothetical studies suggest that stabilisation of metastatic disease and/or symptom burden are worth treatment-related side effects. We examined this premise contemporaneously using qualitative and quantitative methods.

Methods

Patients with metastatic cancers expected to live > 6 months and prescribed drugs aimed at cancer control were interviewed: at baseline, at 6 weeks, at progression, and if treatment was stopped for toxicity. They also completed Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) plus Anti-Angiogenesis (AA) subscale questionnaires at baseline then monthly for 6 months.

Results

Ninety out of 120 (75%) eligible patients participated: 41 (45%) remained on study for 6 months, 36 progressed or died, 4 had treatment breaks, and 9 withdrew due to toxicity. By 6 weeks, 66/69 (96%) patients were experiencing side effects which impacted their activities. Low QoL scores at baseline did not predict a higher risk of death or dropout. At 6-week interviews, as the side effect severity increased, patients were significantly less inclined to view the benefit of cancer control as worthwhile (X2 = 50.7, P < 0.001). Emotional well-being initially improved from baseline by 10 weeks, then gradually returned to baseline levels.

Conclusion

Maintaining QoL is vital to most patients with advanced cancer so minimising treatment-related side effects is essential. As side effect severity increased, drugs that controlled cancer for short periods were not viewed as worthwhile. Patients need to have the therapeutic aims of further anti-cancer treatment explained honestly and sensitively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Demonstrating overall survival (OS) benefit is regarded as a gold standard outcome in oncology trials, alongside improvement of symptoms [1]. Progression-free survival (PFS) or time to progression (TTP) are established if controversial surrogates for OS. Progression, as defined by an increase in tumour(s) size on scans using RECIST criteria, was never originally intended to be utilised as a surrogate for survival [2]. Nevertheless, PFS is increasingly used as a primary outcome measure in trials and for drug licencing approvals. The adoption of PFS is attractive as studies can be shorter, require fewer patients, and provide results faster [3]. A consequence is that many patients with advanced/metastatic disease are prescribed novel drugs that may have demonstrated only PFS improvements or minimal OS benefits. A study of 68 oncology drug indications licenced by the European Medicines Agency 2009–2013 showed that only five had a beneficial effect on Quality of Life (QoL) at the time of licencing [4]. There are scanty data and therefore uncertainty as to whether or not treatments exerting a marginal impact on length of life also improve its quality. Even when patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are included in clinical trials of novel therapies, they are not always chosen carefully enough to include items likely to impact on quality of life. Data may not be collected at appropriate time points, and analyses are rarely integrated with other study outcomes that would enable better understanding of genuine patient-derived benefits [5]. Recent recommendations supplementing existing guidelines on adverse event (AE) reporting have suggested the inclusion of outcomes more relevant to clinicians and patients thereby facilitating more candid shared decision-making [6]. Recommendations include expressing AEs that impact QoL in terms of their severity, frequency, and duration, and the avoidance of vague phrases that describe drugs as ‘safe and well tolerated’.

It is important to understand more about the putative benefits of PFS from a patient perspective [7], in particular to determine if stabilisation of metastatic disease and/or a reduction in the burden of disease symptoms justifies treatment side effects [3, 8]. Baseline data from the AVALPROFS (Assessing the ‘VALue’ to patients of PROgression Free Survival) study focused on the concordance between oncologists and patients about likely benefits, understanding of therapeutic aims, and expectations of treatment [9]. Results showed oncologists were generally more optimistic about the likely benefits of treatment compared with published data from clinical trials and expected 62% of patients to live longer with treatment than without it. Only 52% mentioned palliative care as an option despite increasing evidence that early referral may improve QoL and increase survival [10, 11]. The majority of patients (57%) had ‘no idea’ or were unclear what PFS meant, and 50% believed extension of life to be the primary therapeutic aim. Many of those who recognised that treatment intent was to slow or stop cancer growing, mistakenly thought this meant living longer [9].

Some have questioned whether merely delaying progression without increasing survival time in metastatic disease is even a worthy goal [2]. It seems intuitively reasonable that arresting a tumour’s growth would bring relief and enhance psychological well-being. Conversely, a lack of response to treatment might increase anxiety but few data support these assertions. Furthermore, there have been no contemporaneous rather than hypothetical studies conducted in this area.

We report here further results from AVALPROFS regarding the non-monetary ‘value’ that patients with advanced disease place on the drugs they received; specifically, how long they would require treatment to continue controlling the cancer to make it worthwhile and illustrate the impact treatment-related side effects and disease progression had on QoL and emotional well-being.

Methods

Study design and participants

Participants were recruited between March 2014 and July 2015 from 11 UK cancer centres by members of the clinical team. Oncologists briefly introduced the study to their patients who completed expression of interest forms providing contact details and took study information sheets home to read. Independent researchers followed up approximately 24 h later to organise consent and interview dates. The project was approved by London-Surrey Borders Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 14/LO/0045).

Eligibility criteria

Patients aware of their diagnosis, able to be interviewed in English, with a predicted life expectancy of ≥ 6 months, and who were prescribed drugs with PFS or modest (1–3 months) OS benefits were eligible to join the study.

Assessment measures

Following consultations, during which treatment and care options were discussed, oncologists completed checklists probing information they had provided. The checklist established diagnosis, stage of disease, sites of metastases, treatments received to date, and drugs discussed at recent consultations.

Comprehensive patient interview schedules were developed with members of Independent Cancer Patients' Voice (ICPV), a patient involvement charity. Experienced researchers interviewed patients either face-to-face at home or by telephone if preferred at baseline (within 2 weeks of the consultation), at 6 weeks later, and then at progression or if treatment was stopped due to toxicity. Patients described their understanding of the aims of treatment, side effects experienced, and how they managed them. They graded their most bothersome side effect using abridged descriptions from the Common Toxicity Criteria of Adverse Events (CTCAE) manual (Appendix 1). If not currently experiencing side effects, they indicated what would be their most bothersome side effect. Time trade-off-type questions explored how worthwhile treatment was or would be. Specifically, patients were asked as side effect severity increased how long they would require the drugs to continue controlling cancer to make that treatment worthwhile.

Additionally, patients completed QoL questionnaires: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) [12] and the FACT-Anti-Angiogenesis (AA) subscale which contains side effects pertinent to the cancer drugs prescribed even those without anti-angiogenic modes of action [13]. FACT questionnaires were administered prior to the first and second interviews (6 weeks) and then at 10, 14, 18, and 22 weeks either by post or completed by telephone according to patients’ preferences. Written consent was obtained prior to the first interview.

This paper focuses on:

-

1)

Views patients had about their treatments and side effects

-

2)

The length of time patients would require treatment to continue controlling the cancer if the severity of their most bothersome side effect that they were experiencing increased

-

3)

Analyses of the QoL outcomes that examine predictive factors and the relationship with treatment toxicity and disease progression, illustrating specifically the impact treatment-related side effects have on QoL and emotional well-being

Statistical methods

The interview probes produced categorical data showing proportions of patients who (a) agreed that the treatment-related side effects were worth the benefit of the new treatment and (b) the amount of additional time required for the drug to control the cancer, as the side effect severity increased. Data were examined at baseline and at 6 weeks using chi-square statistics from cumulative logistic ordinal regression analyses [14].

QoL across time was measured using the 27-item FACT-G that comprises four subscales: physical (PWB), functional (FWB), emotional (EWB), and social (SWB) well-being; scores range from 0 to 108. Anti-A scores range from 0 to 96. Mean total FACT subscale scores were calculated at each time point. A trial outcome index (TOI) PWB + FWB + AA subscale (range 0–148) was also calculated. Observed and estimated mean plots were produced over the six study time points. Multivariate linear regression analyses examined factors related to FACT-G and TOI, adjusted for dropout [15]. Some additional details of these analyses are given in Appendix 2. Also, time-to-event analyses using Cox’s relative risk regression model [16] were used to examine the relationship between QoL measures and adverse events. Additionally, QoL was examined based on the groups who stayed on study or withdrew due to progression/death or toxicity.

Findings

Recruitment

Thirty-two oncologists from cancer centres across the UK referred 120 patients with advanced heterogeneous cancers to the study: 27 declined to participate and 3 proved ineligible, 75% (90/120) participated. The largest tumour group was lung cancer (33%; 30/90). Although one entry criterion was a life expectancy > 6 months, 40% (36/90) of patients died or progressed during the 6-month study; 36% (13/36) before the 6-week interview (see Fig. 1). Table 1 shows patients’ baseline demographic characteristics and drugs prescribed.

Patients’ views on side effects

Forty-three (48%) patients at baseline interview were within 2 weeks of starting new treatments, and 21% (9/43) said their side effects (SEs) were worse than expected. At the 6-week interview, a majority of patients (96%; 66/69) were experiencing side effects, the most bothersome of which were fatigue (33%), diarrhoea (17%), and skin rash (15%). These side effects affected the daily activities of most patients (88%; 58/66), and almost a third (30%; 16/54) said hospital and medical staff were unable to help. The most common self-management approaches used were rest (48%; 26/54) and change in diet (19%; 10/54). Others used medications, creams, mouthwash, and painkillers (48%; 26/54). The usefulness of these strategies varied from very (56%; 30/54) to moderately (33%; 18/54) or not at all (11%; 6/54).

Patients’ views at withdrawal of treatment

Table 2 shows some of the feelings expressed by patients who had a treatment break (N = 4), who withdrew due to toxicity (N = 9), or withdrew due to progression (N = 19). Those whose treatment was stopped due to toxicity verbalised more regret than those who stopped due to progression.

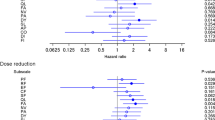

Views on the non-monetary “value” of treatment

Patients were asked to consider their most bothersome side effect and then asked “is (or would) the benefit of the drug in terms of controlling the cancer be worth the following grades of severity – yes, no, unsure.” Patients read the modified CTCAE Grade descriptions for the relevant side effect in ascending order starting at the lowest being experienced or at grade I for patients who had not commenced treatment (see Appendix 1). As the possible side effect severity increased, overall patients were significantly less inclined to feel that the benefit of controlling the cancer would be worthwhile (ordinal regression global X2 = 73.35 on 2 df, P < 0.0001) and this finding remained at the second interview (X2 = 38.22 on 2 df, P < 0.0001). However, there was little intra-patient variability over time; most patients who considered, at baseline, a treatment as worthwhile at a particular threshold, maintained their views at 6 weeks. Notable exceptions were ten patients who at baseline did not consider treatment as worthwhile if they were to develop grade III side effects. They changed opinion at 6 weeks and did consider it worthwhile; seven of these patients were coping with grade II side effects. In contrast, five patients who at baseline felt that treatment would be worthwhile were they to develop grade III side effects, did not think so at 6 weeks, three of whom were experiencing grade II side effects.

For each grade of side effect, patients were asked “how long do you require the treatment to continue to control the cancer for you to consider it a worthwhile treatment for you?” Response options were as follows: at least a month; 3, 6, and 12 months; and > a year. As the side effect severity profiles increased from grades I to III, patients were more likely to require the treatment to control the cancer for longer. This relationship was significant at baseline (X2 = 9.35 on 2 df, P = 0.009) and at 6 weeks (X2 = 7.34 on 2 df, P = 0.026). (Table 3 shows the responses to the trade-off-type questions at baseline and the 6-week interview.)

There was no difference in responses between the three largest groups of patients, lung (N = 30), melanoma (N = 19), and breast (N = 18). Table 4 shows some of the comments made to explain patients’ choice; a proportion of patients (N = 19/40) believed that 1 month of cancer control was worthwhile even if they developed grade III side effects from their treatment.

Quality of life

Attrition over time is usual in most studies of advanced metastatic disease due to progression of disease or death. In AVALPROFS, questionnaire completion dropped from 99% (89/90) at baseline to 53% (48/90) by 22 weeks (see Fig. 1 for reasons). In time to event analyses no relationship was demonstrated between baseline QoL and dropout for any reason.

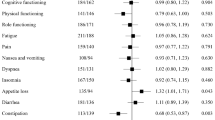

Supplementary Fig. 1a, b shows the overall observed means and estimated means for the FACT-G and TOI respectively. The latter are adjusted for dropout, and the most likely scenario is that low scores are associated with a higher risk of death/dropout. Adjusted means plot for the emotional well-being subscale showed an improvement from baseline by 10 weeks, which gradually returned to baseline levels (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Univariate linear regression analyses of the FACT-G and TOI adjusted for dropout showed that in the TOI analyses, lung cancer patients and then breast and other cancers had the lowest scores (Supplementary Table 1). Also, scores were lower in those diagnosed recently with metastatic disease and for those whose diagnosis of advanced disease was > 2 years, relative to those in the 1–2-year category. Multiple various inhibitors and other treatments were associated with lower scores while males had higher scores. These various factors are highly correlated, and when all are included in a multivariate regression model, the only significant effects are associated tumour site and time since diagnosis in the TOI analysis.

Examination of the longitudinal data subdivided by patients who stayed on study compared to those who progressed/died, or experienced toxicity, showed the estimated means of the progression/died group lie below the toxicity group, whereas for the observed means, it is the opposite.

Discussion

Most previous work in this area has relied on hypothetical data collected from patients who are well. Retention of patients in the AVALPROFS study was undoubtedly challenging; 19% (17) of patients died (15 within 10 weeks) despite study eligibility criteria of > 6-month survival. This suggests that over-optimistic prognostication and prescribing led to ineffective and quite toxic therapies being delivered to some patients. Previous authors have commented that too many patients, especially those with haematological malignancies and lung cancer, are receiving anti-cancer treatments and experiencing side effects within the last 30 days of life [17, 18]. Prognostication is often inaccurate despite efforts to improve it [19]. Over optimism on behalf of the prescribing oncologist or a failure to discuss realistic survival benefits highlights some ethical challenges regarding the veracity of informed decision-making [20, 21].

Most side effects reported in AVALPROFS occurred within 2 weeks of starting treatment, and overall, from the patients’ perspective, fatigue was considered most bothersome. Although fatigue is a prominent side effect of systemic anti-cancer therapies, it is also a symptom of advancing disease and might not be directly treatment related for all patients. A fifth of patients reported side effects as being worse than anticipated, but those interviewed at progression, or when stopping drugs due to toxicity, felt that treatment had nevertheless been worthwhile. These findings demonstrate the need to maintain research into ameliorative interventions for the more common side effects experienced.

Inevitably, attrition will be notable in any longitudinal study of patients with a poor prognosis. As outlined in our supplementary material, we have attempted to adjust for this using a non-parametric-based approach that links the outcome of interest with the probability of having an observation at a time point. The adjustments arising from this approach for the means at each follow-up time point were dramatic, and therefore, this same general method of adjustment was used for regression analyses. The effect of the adjustment is both to shift estimated effects and to increase the uncertainty concerning estimation. While it can never be possible to adjust for attrition completely and definitively, and untestable assumptions must be made in any attempt to do so, we feel that the presented results in this paper do significantly reduce the attrition bias that otherwise would have been present.

Few studies have data on whether or not arresting a tumour’s growth brings relief and enhances psychological well-being. We found that overall emotional well-being increased at 10 weeks but then returned to baseline levels. This may reflect an initial optimism at being prescribed a new treatment and then the realisation that life had not improved dramatically or had declined due to the impact of side effects on QoL.

Patient QoL and well-being need to be considered equally alongside length of life when exploring patient priorities and treatment decisions in advanced disease, but concordance between the severity of side effects reported on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and those noted by physicians is rather poor [22, 23]. A recent review showed that although cancer treatment-related toxicities vary in severity, typically, only grades 3 and 4 are recorded and reported in clinical trials, thus diluting recognition of frequency and severity [24]. Part of the lack of concordance between patients and clinician reports may be the way in which questions are asked; PROMs such as the FACT-G require patients to indicate over the last 7 days how bothered they have been (not at all, a little, somewhat, very much) in response to each item. In contrast, doctors may be selective and exhibit ascertainment bias by probing only about expected or most clinically worrying Adverse Events (AEs) then classifying them on case report forms using the CTCAE criteria. More accurate data about harms and benefits are nevertheless important to help decision-making when patients are offered novel therapies that are unlikely to increase survival significantly.

We recognise that the sample size in this study is quite small; however, it is much larger than many phase I/II cancer trials examining drug combinations, for example, bevacizumab and erlotinib (n = 40) [25] or paclitaxel plus carboplatin and bevacizumab as first-line treatment in triple-negative metastatic breast cancer (n = 45) [26], neither of which included QoL assessments.

The authors are aware that this area is an emotive subject, but patients deserve to have more sensitive discussions about plausible outcomes from further anti-cancer treatments together with less nihilism about supportive care options: if not otherwise, to quote Nicholas Christakis, “patients die deaths they deplore in locations they despise” [27].

Conclusions

Discussions about disease progression and advantages of further active treatment in the advanced setting are undoubtedly challenging and nuanced. Many factors must be balanced. The number of patients who either died, progressed, or withdrew due to toxicity in AVALPROFS was somewhat disquieting. It is essential that clinicians retain perspective as to what constitutes meaningful gains for their patients, namely symptom and/or QoL improvements not just arrest of tumour burden on imaging or tumour marker reductions. We can accept that it is not entirely fair to label what appears to be over-optimistic prognostication as a misreading of published statistical data. It is true that studies give headline reports of a median PFS and that applying a population median to an individual will not always be appropriate. It is also true however that consistently anticipating patients to have responses on the right side of that median is statistically naive and a belief that makes gamblers poor. Clinicians need to revisit these priorities with patients regularly as a treatment protocol is given since these data show that patient views will change as treatment is experienced. We also need more effective ameliorative interventions to help patients who experience the common class effects of many novel drugs in particular for fatigue and diarrhoea. Finally, oncologists who undoubtedly care deeply about their patients need to develop an acute awareness of the fact that in their desire to maintain patients’ hope, they may be as overly optimistic about the putative benefits of many novel drugs offering only PFS, as are their patients.

References

Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, Debono DJ, Berry SR, Wollins DS, Hayes DM, von Roenn J, Schnipper LE, American Society of Clinical Oncology (2011) American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. JCO 29:755–760

Booth CM, Eisenhauer AF (2012) Progression-free survival: meaningful or simply measurable? JCO 30(10):1030–1033

Fallowfield LJ, Fleissig A (2012) The value of progression-free survival to patients with advanced-stage cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 9(1):41–47

Davis C, Naci H, Gurpinar E, Poplavska E, Pinto A, Aggarwal A (2017) Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009–13. BMJ 359:j4530

Amir E, Seruga B, Kwong R, Tannock IF, Ocaña A (2012) Poor correlation between progression-free and overall survival in modern clinical trials: are composite endpoints the answer? EJC 48(3):385–388

Lineberry N, Berlin JA, Mansi B et al (2016) Recommendations to improve adverse event reporting in clinical trial publications: a joint pharmaceutical industry/journal editor perspective. BMJ 355:i5078

Bridges JF, Mohamed AF, Finnern HW et al (2012) Patients’ preferences for treatment outcomes for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a conjoint analysis. Lung Cancer 77(1):224–231

Niraula S, Seruga B, Ocana A, Shao T, Goldstein R, Tannock IF, Amir E (2012) The price we pay for progress: a meta-analysis of harms of newly approved anticancer drugs. JCO 30(24):3012–3019

Fallowfield LJ, Catt SL, May SF et al (2016) Therapeutic aims of drugs offering only progression-free survival are misunderstood by patients, and oncologists may be overly optimistic about likely benefits. Supp Care Ca 13:1–8

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742

Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, Friederich H, Villalobos M et al (2017, Issue 6. Art. No.: CD011129) Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011129.pub2

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scale: development and validation of the general measure. JCO 11:570–579

Kaiser K, Beaumont JL, Webster K, Yount SE, Wagner LI, Kuzel TM, Cella D (2015) Development and validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy–anti-angiogenesis subscale. Cancer Med 4(5):690–698

McCullagh P (1980) Regression models for ordinal data (with discussion). J R Stat Soc B 42:109–142

Farewell DM (2010) Marginal analyses of longitudinal data with an informative pattern of observations. Biometrika 97:65–78

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life tables (with discussion). J R Stat Soc (B) 34:187–220

Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, Yennu S, Bruera E (2013) Attrition rates, reasons, and predictive factors in supportive care and palliative oncology clinical trials. Cancer 119(5):1098–1105

Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, Paulk ME, LeBlanc TW, Schneider BJ, Garrido MM, Reid MC, Berlin DA, Adelson KB, Neugut AI, Maciejewski PK (2015) Chemotherapy use, performance status and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol 1(6):778–784

Stone PC, Lund S (2007) Predicting prognosis in patients with advanced cancer. Annals Oncol 18:971–976

Audrey S, Abel J, Blazeby JM, Falk S, Campbell R (2008) What oncologists tell patients about survival benefits of palliative chemotherapy and implications for informed consent: qualitative study. BMJ 337:a752

Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG (2015) Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. JCO 33(32):3809–3816

Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, Barz A, Sit L, Fruscione M, Appawu M, Iasonos A, Atkinson T, Goldfarb S, Culkin A, Kris MG, Schrag D (2009) Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. JNCI 101(23):1624–1632

Fellowes D, Fallowfield LJ, Saunders CM et al (2001) Tolerability of hormone therapies for breast cancer: how informative are documented symptom profiles in medical notes for “well tolerated” treatments? BCRT 66(1):73–78

Carlotto A, Hogsett VL, Maiorini EM, Razulis JG, Sonis ST (2013) The economic burden of toxicities associated with cancer treatment: review of the literature and analysis of nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea, oral mucositis and fatigue. PharmacoEconomics 31(9):753–766

Herbst RS, Johnson DH, Mininberg E, Carbone DP, Henderson T, Kim ES, Blumenschein G Jr, Lee JJ, Liu DD, Truong MT, Hong WK, Tran H, Tsao A, Xie D, Ramies DA, Mass R, Seshagiri S, Eberhard DA, Kelley SK, Sandler A (2005) Phase I/II trial evaluating the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody bevacizumab in combination with the HER-1/epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib for patients with recurrent non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(11):2544–2555

Nikolaou M, Saloustros E, Polyzos A, Christophyllakis C, Kentepozidis N, Vamvakas L, Kalbakis K, Agelaki S, Georgoulias V, Mavroudis D (2016) Final results of weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. A multicenter phase I–II trial by the Hellenic Oncology Research Group, Ann Oncol, Volume 27, Issue suppl_6, 242P, https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw365.21

Christakis NA (1999) Death foretold: prophecy and prognosis in medical care. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients who gave up their time to participate, the clinical staff, and recruiting clinicians, Jaishree Bhosle, Juliet Brock, Mick Button, Robert Crellin, Maxine Flubacher, Tom Geldart, Rebecca Herbertson, Tamas Hickish, Stephen Johnston, Rachel Jones, Joanne Kosmin, Satish Kumar, Kate Lankester, John McGrane, Andreas Makris, Russell Moule, Mary O’Brien, Richard Osborne, Gargi Patel, Stefania Redana, Adam Sharp, Gia Schiavon, Joanne Simpson, Toby Talbot, Andrew Webb, Sarah Westwell, Duncan Wheatley, and Belinda Yeo and Angela Fry. We would also like to thank the members of the patient advocate Charity, Independent Cancer Patients’ Voice who reviewed the protocol, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an Investigator Led Grant from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Lesley Fallowfield has received grant funding and speaker honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The project was approved by London-Surrey Borders Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 14/LO/0045).

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jenkins, V., Farewell, V., May, S. et al. Do drugs offering only PFS maintain quality of life sufficiently from a patient’s perspective? Results from AVALPROFS (Assessing the ‘VALue’ to patients of PROgression Free Survival) study. Support Care Cancer 26, 3941–3949 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4273-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4273-3