Abstract

This study is based on the observation of sawtooth wave-like pressure changes (STW) observed during repetitive gas emissions in a syrup eruption experiment. Similar waveforms are observed at many active volcanoes as geodetic signals. By studying the physics of such experiments, we often find new ideas and insights that are applicable to natural volcanic phenomena. We consequently try identifying the features common to both our experimental system and natural volcanic systems. We infer that the oscillatory mechanism in our experiment is similar to flow-induced oscillation controlled by a coupling between elastic capacitance and variable flow resistance. We developed an elementary pipe–chamber system to quantitatively test this hypothesis. We observed three distinct oscillatory patterns: periodic STW, non-STW, and nonperiodic STW. A mathematical model is constructed to support the hypothesis and to enable comparison with existing models of volcanic systems. Models of flow-induced volcanic oscillations are mathematically similar to the model derived from our experimental system. Our results indicate that flow pattern transitions are essential for oscillatory behavior during gas emission. An important finding is that cycle periodicity and fluctuation are controlled by interactions between upward and downward flow within the pipe, especially during the termination of gas emission and the transition to the next cycle. Similar interactions occur in natural volcanoes: during the termination of an explosive eruption, fall-back or drain-back of ejected materials may modulate the explosivity and periodicity of the next eruption cycle. Our experimental system may provide a useful tool for understanding the oscillatory behavior of natural volcanic systems. This study may also give a proof that the original eruption experiment provides a useful tool for explaining the dynamics of oscillatory and eruptive behaviors of natural volcanic systems in educational (e.g., Open Day) demonstrations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Experiments using common materials to simulate geological processes are effective tools for Earth science education and outreach (e.g., Coffey 2008; Kurita et al. 2008; Deus et al. 2011). In addition, studying the physics of experimental systems frequently provides novel ideas and insights that can be applied to natural phenomena (e.g., Scott et al. 1986; Mader et al. 2004; Iga and Kimura 2007; Kumagai et al. 2008).

This study was inspired by a sugar syrup eruption experiment (Fig. 1a) conducted as an exhibition during an institute open house. Through this experiment, we tried to introduce the structure of volcanoes, various geophysical signals observed with volcanic activity, and dynamics of an eruption. We used a bottle linked to a pipe as an analogue system for a magma chamber and a volcanic conduit. Pressure in the bottle is measured to simulate geodetic signals. Syrup with citric acid was mixed with baking powder in the bottle confined by plugging the top of the pipe. Generation of CO2 bubbles increased the internal pressure. Plug opening triggered a vigorous syrup eruption and rapid pressure release, followed by intermittent weak gas emissions similar to sequences observed during natural volcanic events. For example, dome collapse triggered a sub-Plinian eruption followed by repetitive Vulcanian eruptions during the 1997 eruption of the Soufriére Hills Volcano, Montserrat (Druitt et al. 2002). During the experiment, repetitive gas emission was accompanied by sawtooth wave-like pressure changes (STW) in the bottle (Fig. 1). The observed asymmetric waveform is similar to geodetic signals that are sometimes observed at active volcanoes (e.g., Iguchi et al. 2008; Takeo et al. 2013; Genco et al. 2014). This study focuses on STW and aims to identify the features common to both the experimental STW and natural volcanic oscillations.

Inflation–deflation cycles of volcanic edifices are observed at many active systems and are interpreted as geodetic signals associated with magma and gas flow (e.g., Ohminato et al. 1998; Fujita et al. 2004; Iguchi et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2010; Genco and Ripepe 2010; Fontaine et al. 2014). These geodetic oscillations display a variety of waveform shapes, commonly including asymmetric waveforms consisting of alternating gradual change and rapid recovery. Gradual inflation and abrupt deflation cycles are commonly associated with repetitive eruptions (e.g., Strombolian eruptions: Genco and Ripepe (2010); Vulcanian explosions: Iguchi et al. (2008); Takeo et al. (2013); and geysers: Nishimura et al. (2006)). During dome-building eruptions, similar cycles (Voight et al. 1998) and reverse cycles consisting of gradual deflation and rapid inflation (Anderson et al. 2010) have been reported. Reverse cycles have also been recorded during caldera collapse (Fujita et al. 2004; Fontaine et al. 2014) and magma drain-back (Fukuyama 1988).

Asymmetric volcanic oscillations are reproduced by flow-induced oscillation models that include coupling between elastic capacitance and variable flow resistance (Whitehead and Helfrich 1991; Ida 1996; Wylie et al. 1999; Maeda 2000; Barmin et al. 2002; Melnik and Sparks 2005; Kozono and Koyaguchi 2012; De’ Michieli Vitturi et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2018). Existing models commonly assume that elastic capacitance is related to chamber elasticity and/or magma compressibility. However, different mechanisms of variable flow resistance have been proposed, including viscosity dependence on temperature distribution in the conduit (Whitehead and Helfrich 1991); changes in conduit radius due to the deformation of surrounding rocks, which depends on overpressure (Ida 1996; Maeda 2000; Chen et al. 2018); velocity-dependent volatile and/or crystal contents, which control magma viscosity (Wylie et al. 1999; Barmin et al. 2002); and stick–slip motion with rate-dependent friction (Iverson et al. 2006). Flow-induced oscillation can also be generated by the rate-dependent effective density of magma in a conduit and the competition between bubble growth and escape (Woods and Koyaguchi 1994). The combined effects of these mechanisms have been investigated through advanced numerical methods (Melnik and Sparks 2005; Kozono and Koyaguchi 2012; De’ Michieli Vitturi et al. 2013).

Various mechanisms of flow-induced oscillations have been identified in laboratory experiments, and possible applications of such mechanisms to natural volcanic oscillations have been proposed. For example, Lane et al. (2008) reported cyclic pressure changes resulting from alternating periods of Poiseuille flow and plug flow in a vertical pipe and compared the oscillation to tilt cycles during dome-building eruptions. Self-induced pressure perturbations repeatedly occur during flow from a chamber through a pipe for fluids with complex rheologies with a negative correlation between shear stress and shear rate (Den Doelder et al. 1998). Similar oscillations might occur during flow of magma which has a complex rheology (Kurokawa 2016). A self-induced oscillation known as a “pressure drop oscillation” occurs in systems with a sufficiently compressible volume in a chamber connected upstream to a boiling pipe (Ozawa et al. 1979). Fujita et al. (2004) applied the mechanism to explain oscillatory behavior observed in the 2000 Miyakejima caldera collapse.

During the STW stage of our eruption experiment, large bubbles slowly ascended the pipe as a slug flow. Ascending slug flow is regarded as an analogue for Strombolian eruptions and has been studied in several experiments (Jaupart and Vergniolle 1989; James et al. 2004, 2006; Azzopardi et al. 2014; Del Bello et al. 2015; Pioli et al. 2017). In these experiments, pressure fluctuations in the conduit are due to bubble motion, which is controlled by viscous, inertia and gravity forces, by bubble expansion, and by the boundary conditions including the geometry of the system. The STW in our experiment were generated by slug flow in a pipe connected to a chamber and did not occur when the chamber was disconnected. Therefore, we assume that the STW were not generated by bubble motion alone but were similar to flow-induced oscillations controlled by coupling between elastic capacitance (the bottle) and variable flow resistance of the liquid syrup flowing up the pipe.

To quantitatively test this hypothesis, we conducted controlled experiments involving gas–liquid flow in a vertical pipe connected to a gas chamber. We observed three distinct oscillatory patterns: periodic STW, non-STW, and nonperiodic STW, all of which have been observed in natural volcanoes (e.g., Fukuyama (1988) for periodic STW, Voight et al. (1998) for non-STW, and Iguchi et al. (2008) for nonperiodic STW). We find that waveform shapes are related to flow patterns in the pipe. We then derived a mathematical model for the experimental system in which we treat the physical quantities as lumped parameters to represent the system by ordinary differential equations. This derivation allows the experimental system to be compared with models for natural volcanic systems. We then identify the mathematical similarities and differences among our system and existing models of volcanic oscillation. Although our experiment differs from scaled experiments that simulate slug flow in a volcanic conduit (e.g., Jaupart and Vergniolle 1989; James et al. 2004, 2006; Del Bello et al. 2015), our experimental observations, combined with comparison to its mathematical equivalent, provide new insights into volcanic systems.

Experimental method

The experimental system comprised a chamber and pipe, where a constant gas flux was maintained in the chamber, and the gas–liquid flow in the pipe (Fig. 2). The chamber, pipe, and connecting joint were constructed using acrylic glass to ensure rigidity and enable direct observations. The chamber was partially filled with water to adjust the compressible gas volume (Vc) (Fig. 2, blue part at the bottom of the chamber). Vc is maintained at a constant value during each experimental run.

Gas flux into the chamber (Qin) was regulated by a microneedle valve (IBS FMNV2) that ensured a constant gas flux of between 10−7 and 10−6 m3/s. We used sugar syrup diluted in distilled water as the liquid phase. The liquid behaved as a Newtonian fluid, and we measured its viscosity using a BOHLIN CVO Rheometer, and adjusted it to 1 Pa s at the experimental temperature of 25 °C. Injected gas flowed through the pipe and forced the liquid residing in the pipe upward, resulting in gas–liquid flow within the pipe.

A pressure sensor (KISTLER 701A with a 5011A charge amplifier) was installed to measure pressure changes in the chamber, and a microphone (Brüel & Kjær 4193+2669L with a Nexus 2690 signal conditioner) was mounted to the top of the pipe. Data were sampled at 10 kHz using a PC-based data acquisition system (DEWETRON DEWE-211).

A high-speed black-and-white camera (Photoron FASTCAM Mini) was synchronized with the data acquisition PC and was focused on the lowermost 200 mm of the pipe, where gas–liquid flow occurred. The field of view was illuminated by a flat backlight source. We used a pale-color syrup so as to improve the visibility of the liquid phase against the gas phase and the pipe. Dark areas were thus shaded according to the thickness of the liquid across the pipe. We used the resulting distribution of light intensity to observe flow patterns.

The controlled experimental parameters were Vc, Qin, and the amount of syrup in the pipe, as defined by the initial syrup height Hs. These parameters were fixed during each experimental run. We conducted 143 runs in total, during which the parameters varied from 1.5 to 7.1 × 10−7 m3/s for Qin, 20 to 157 cm3 for Vc, and 60 to 150 mm for Hs. Data were recorded from the beginning of each run for at least 20 pressure cycles.

Experimental results

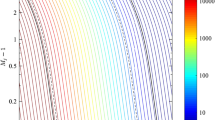

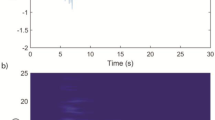

We have divided our experimental observations into three groups: periodic STW, non-STW, and nonperiodic STW (Fig. 3). These different waveform shapes were created by varying Qin and Vc with a fixed Hs of 90 mm.

Pressure change in the chamber (red) and the microphone at the pipe exit (blue). Waveforms and spectra of pressure changes are shown for a, b periodic STW with Qin = 0.43 cm3/s and Vc = 157 cm3; c, d non-STW with Qin = 0.23 cm3/s and Vc = 20 cm3; and e, f nonperiodic STW with Qin = 0.71 cm3/s and Vc = 157 cm3

A periodic STW was observed for relatively large Qin and Vc (Figs. 3a and 4c). Pressure-change waveform data were low-pass filtered at 30 Hz and detrended before being used to calculate spectra and root mean squares (RMS). A clear, regularly repeated STW signal was observed (Fig. 3a). The periodicity is represented by sharp harmonic peaks in the spectra, extending to higher overtones (Fig. 3b). The STW period is determined using the frequency of the fundamental mode. The period and RMS of STW gradually increase with Vc and decrease with Qin (Fig. 4a, b). Video data allow direct observations of flow behavior in the pipe (Movie 1). We define a liquid slug as a continuous zone of liquid that bridges the pipe (Fig. 5a). Liquid slugs are separated by gas slugs, which are large bubbles with diameters similar to the pipe diameter. An ascending flow of alternating gas and liquid slugs (e.g., at 5 and 7 s in Fig. 5a) is hereafter referred to as “slug flow.” As liquid slugs ascend, a film of liquid descends along the pipe wall, which is referred to here as “downward film flow.” As slug flow accelerates, liquid slugs become shorter and are stretched forming membrane-like structures, which eventually rupture (i.e., gas bursting occurs; e.g., between 7 and 9 s in Fig. 5a). Acceleration burst occurs simultaneously for all gas slugs, producing a countercurrent annular flow (hereafter referred to as an annular flow) characterized by continuity of the ascending gas phase within the pipe core and a downward film flow around it (Wallis 1969; Hewitt and Hall-Taylor 1970). We define this flow-pattern transition as slug-to-annular flow transition. These terms (annular flow and slug-to-annular flow transition) are different from those more commonly used for co-current gas–liquid flow in fluid engineering (Wallis 1969; Hewitt and Hall-Taylor 1970) and in volcanology (e.g., Vergniolle and Jaupart 1986). During annular flow, surface disturbances, which are generated by gas slug bursting, descend along the pipe wall (e.g., between 9 and 13 s in Fig. 5a). At the bottom of the pipe, liquid slugs are produced by the growth of a surface disturbance generated during downward film flow (e.g., between 9 and 11 s in Fig. 5a), which is hereafter referred to as “slug reconstruction.” Slug reconstruction leads to an annular-to-slug flow transition. With time, the sequence of slug-to-annular and annular-to-slug flow transitions was then repeated (e.g., from 11 s in Fig. 5a).

Comparison of experimental and numerical results, showing the period (a) and RMS (b) of the pressure data, and the waveforms that were produced when the input parameters Qin and Vc were provided (c). Markers represent experimental results: squares = periodic STW, crosses = non-STW, and circles = nonperiodic STW. Numerical results are indicated by broken (with an original value of w listed in Table 1) and solid lines (with a larger value of w that is 1.6 times than original value). Coloring of markers and lines indicates different values of Qin. Brown solid line in c represents the model prediction (D = 0 and G < α) with ξ = 1.11 × 106 (Γ = 0.86), whereas the dashed line represents the model prediction without considering the effects of surface tension (Γ = 0)

a Sequential photographs corresponding to Fig. 3a. Slug flow (S) and annular flow (A) are observed to alternate. Shading corresponds to the thickness of liquid as measured across the diameter of the pipe. b Example of a time–height representation of sequential photographs. The corresponding time and height are shown on the y- and x-axes, respectively. The thickness of the liquid along the light path is indicated in color. Ascending red trails represent liquid slugs, while descending yellow–red stripes represent surface disturbances during downward film flow. The ascending liquid slug is indicated by the white rectangle and is used for image analysis in Fig. 11

For each video frame, a 5 × 740-pixel column (Fig. 5a) was extracted and averaged over its 5-pixel width to obtain a 1 × 740-pixel vertical column. The columns were then laterally stacked and the grayscale shading was converted to color (blue to red) to obtain the representation given in Fig. 5b. These representations of the temporal evolution of the flow reveal that liquid slugs accelerate and disappear during slug-to-annular flow transitions. Descending surface disturbances are absorbed by ascending liquid slugs. A red color appears at the bottom of the pipe when a liquid blob starts to grow, and remains until slug reconstruction is complete. A comparison between flow images and waveforms is shown in Fig. 6. For periodic STW, slug flow is observed during the period of gradual pressure increase, while slug-to-annular flow transitions coincide with abrupt pressure drops (Fig. 6a). Flow patterns are regular during each cycle when periodic STW are recorded.

a–c Comparison of pressure change waveforms and flow patterns from Fig. 3a, c, and e

Relatively small Qin and Vc yield non-STW waveforms (Figs. 3c, 4c, and 6b), displaying no abrupt drop in pressure. Moreover, these waveforms have no discernible periodic features, resulting in spectra that lack clear harmonic peaks. The peak frequencies of pressure changes can be used to determine the period of the experimental data (e.g., Fig. 3d). Slug flow is observed to ascend continuously within the pipe (Movie 2). The uppermost liquid slug undergoes a significant reduction in length, forming a membrane-like structure that then ruptures. Ruptures are not observed in the following liquid slugs; consequently, we observed no slug-to-annular flow transitions. Although there is a periodic rise and fall of the top surface of a gas/liquid column in a sawtooth wave-like manner which is similar to a pattern reported in Azzopardi et al. (2014), sawtooth wave-like pressure changes do not appear.

Nonperiodic STW are observed when Qin is large (Figs. 3e, 4c, and 6c; Movie 3). These waveforms display STW features but contain no clear harmonic spectra (Fig. 3f). STW cycles are associated with slug-to-annular flow transitions (Fig. 6c), similar to the periodic STW; however, each slug-flow regime displays a distinct flow pattern.

Mathematical model

We now construct a mathematical model that includes the two essential factors of elastic capacitance and variable flow resistance, in a similar manner to the existing lumped parameter model for flow-induced instabilities in volcanic systems (Ida 1996; Wylie et al. 1999; Maeda 2000; Barmin et al. 2002; Nakanishi and Koyaguchi 2008).

An illustration of the model and definition of the parameters are provided in Fig. 7a–c and Table 1. For simplification, we represent the multiple liquid slugs observed in the experiment as a single large liquid slug.

Schematic image of mathematical models of the experiment (a–c) and natural volcanic systems (d), modified from Nakanishi and Koyaguchi (2008)

Basic equations

We consider a volume flux of gas Qin into the chamber with volume Vc. Both the liquid slug and gas in the pipe move upward at velocity u. We define the volume flux in the pipe as Q = πa2u and the area fraction of gas flow in the pipe as α = r2/a2, where a is the pipe radius and r is the radius of the gas flow (Fig. 7a–c). Then, the volume flux of gas in the pipe is defined as αQ.

We define elastic capacitance using:

where t is time, p is the excess pressure in the chamber, and P0 is atmospheric pressure. In Eq. (1), we consider the compressibility of gas in the chamber to be fixed at 1/P0, neglecting the effects of changes in temperature and pressure. Equation (1) describes the elastic behavior of the gas chamber. If the density difference between inflow into the chamber (Qin) and outflow though the pipe (αQ) is negligible, then Eq. (1) is regarded as the mass conservation equation. This is a reasonable approximation because p ≪ P0. For simplicity, we treat r (and thus α in Eq. (1)) as constant; however, a spatiotemporal change in r due to surface disturbance of downward flow was observed during the experiment (Fig. 5b).

For variable flow resistance, we assume that flow of gas and liquid in the pipe follows the Poiseuille flow relation. We also consider the effects of hydrostatic pressure in the pipe and surface tension immediately prior to film rupture. Thus, we obtain

where μv and ρv are the average viscosity and density of the slug flow in the pipe, respectively, L is the pipe length, g is gravitational acceleration, and Δp is the overpressure caused by surface tension. The values of μv and ρv are respectively given by

where μ and ρ are the viscosity and density of the liquid, respectively, and L∗ is the total liquid slug length. We disregard flow resistance to the motion of the gas slug because the viscosity of the liquid is higher than that of the gas by five orders of magnitude. Although L is not included in the model, it is retained to allow comparison with existing models. The representation of flow resistance in Eq. (2) based on the Poiseuille flow approximation is inadequate when a liquid slug becomes a thin membrane. However, at this state, overpressure due to surface tension (Δp) is considered more important than viscous resistance. We introduce the term Δp, which was constrained by image analysis, in a form to correct for the effective viscosity, resulting in an empirical function including L∗ and Q:

where Lc is the critical length of the liquid slug when the term begins to apply and ξ is a fitting parameter (see Appendix). By combining Eqs. (2) and (5), and differentiating with respect to time, we obtain

where μE is the effective viscosity and Γ is a dimensionless parameter representing the ratio of the effective viscosity due to surface tension to the liquid viscosity.

Temporal change in L∗ is a key parameter for variable flow resistance in the pipe. According to the conservation of liquid volume in the pipe, we have

where Hs is the initial syrup height and Hw is the top of the flow (Fig. 7a–c). The area fraction of gas flow in the annular flow is considered to be the same constant α as that of the gas flow of the slug flow. The velocity of Hw depends on the head position (x) of the slug flow as defined by

where L∗i is the initial length of the liquid slug. When x < Hw, Hw descends along the pipe at a constant velocity, w (see Appendix). When x = Hw, the velocity of Hw is equal to the velocity of the liquid slug (Fig. 7b). Differentiating Eq. (9) with respect to time, we obtain

where W = wπa2. The downward film flow flux is given by (1 − α)W.

Dimensionless equations

The variables p, Q, t, L∗, x, Hw, ρv, and μE and the constants Qin, W, Lc, and μ are scaled in the model using the following relations: p = PuP′, Q = QuQ′, t = Tut′, \( {L}_{\ast }=L{L}_{\ast}^{\prime } \), \( x=\frac{Q_{\mathrm{u}}{T}_{\mathrm{u}}}{\pi {a}^2}\ {x}^{\prime } \), \( {H}_{\mathrm{w}}=\frac{Q_{\mathrm{u}}{T}_{\mathrm{u}}}{\pi {a}^2}{H}_{\mathrm{w}}^{\prime } \), \( {\rho}_{\mathrm{v}}=\rho {\rho}_{\mathrm{v}}^{\prime } \), \( {\mu}_{\mathrm{E}}={\mu}_{\mathrm{A}}{\mu}_{\mathrm{E}}^{\prime } \), \( {Q}_{\mathrm{in}}={Q}_{\mathrm{u}}{Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime } \), W = QuW′, \( {L}_{\mathrm{c}}=L{L}_{\mathrm{c}}^{\prime } \), and μ = μAμ′, where ′ indicates a dimensionless number. Viscosity is scaled by μA, which is the effective viscosity of the gas slug. Although μA is not explicitly used in the model, it enables scaling. The scaling units Pu, Qu, and Tu, and the dimensionless parameter A, are respectively defined by

An additional dimensionless parameter G is defined by

Scaling factors were selected to produce dimensionless equations with comparable forms to existing flow-induced models (e.g., Ida 1996; Wylie et al. 1999; Barmin et al. 2002; Nakanishi and Koyaguchi 2008; Chen et al. 2018) for volcanic systems (Table 2). The dimensionless forms of Eqs. (1), (6), (7), (4), and (11) are respectively as follows:

Definitions and values for the dimensionless parameters are listed in Table 1.

Mathematical analysis of the system behavior

For dp′/dt′, Eq. (14) indicates that its sign changes from positive to negative with increasing Q′ beyond \( {Q}^{\prime }={Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime }/\alpha \). For dQ′/dt′, Eq. (15) depends on the value of x′ relative to \( {H}_{\mathrm{w}}^{\prime } \). By combining Eqs. (16) and (18), we rewrite Eq. (15) as

F1(Q′) indicates that as Q′ increases from 0, it will converge to a constant flux, satisfying F1 = 0, which is shown to be always less than \( {Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime }/\alpha \). This condition indicates that pressure will increase while \( {x}^{\prime }<{H}_{\mathrm{w}}^{\prime } \), due to the increasing mass of gas within the chamber. When \( {x}^{\prime }={H}_{\mathrm{w}}^{\prime } \), the quadratic function F2(Q′) controls the behavior of Eq. (19). We set Γ to equal 0 or 0.86 (Table 1), so that 1 − Γ > 0 is always satisfied. The discriminant of F2(Q′) is given by

When G > α, Q′ is unstable because for Q′ > 0, F2 is always positive and monotonically increases. Therefore, Q′ increases consistently and will not converge on a fixed value. When G < α and D < 0, F2 is always positive and Q′continuously increases. If D > 0, Q′ increases and converges on a value that satisfies F2 = 0. The boundary defining whether or not Q′ will continuously increase (G < α and D = 0) is a function of Qin and Vc and is shown in Fig. 4c. Compared with the experimental data, we find that STW are observed above this boundary. The same boundary, calculated without including the surface tension term (Γ = 0), is also shown in Fig. 4c. Our results indicate that this boundary is sensitive to the effective viscosity used in the model.

Calculation method

Equations (1), (6), (10), and (11) are solved numerically using the Runge–Kutta method (Fig. 8). Here we use dimensional variables to allow direct comparisons with experimental data. The values of L∗, x, Q, and p at the beginning of a cycle are referred to as “initial values” and are indicated by the subscript i. Sequential photographs in which a liquid slug is reproduced at the bottom of the pipe indicate that L∗i and xi are equal to 2 mm. Parameter Qi is assumed to be 0, meaning that pi represents the hydrostatic pressure in the pipe (pi = ρgL∗i). The transition from slug-to-annular flow is regarded as occurring at L∗ = 0, and slug reconstruction is assumed to begin immediately. The time required to form a new liquid slug is calculated by considering the conservation of liquid volume in the pipe. The new liquid slug grows as it is fed by downward film flow at a constant volume flux of ∣(1 − α)W∣. When it reaches a volume of πr2L∗i, slug reconstruction is completed and a new STW cycle begins.

Example of numerical results for Qin = 0.15 cm3/s and Vc = 180 cm3; black solid line is for ξ = 1.11 × 106 (Γ = 0.86) and dotted line is for ξ = 0 (Γ = 0). Time=0 corresponds to the time when slug flow starts to ascend. a Excess pressure. b Head position of the liquid slug. Blue line indicates Hw. c Flux in the pipe. d Total liquid slug length

The model periodicity is defined by the duration from a completion of liquid slug formation to the next. For comparison with the experimental results, the model amplitude is evaluated using RMS. We removed the mean pressure change before calculating RMS.

Periodic STW and non-STW

Examples of the numerical results are shown in Figs. 8 (one cycle of STW) and 9a (periodic STW). The calculated period and RMS values are indicated in Fig. 4a, b by broken lines. They are smaller than the experimental results by a factor of 2 to 3. We suggest that this discrepancy results from the development of surface disturbances during downward film flow, which effectively increases the growth rate of the liquid slug length (dL∗/dt). To test this hypothesis, we applied a model with an arbitrarily large w (average downward film velocity) so as to magnify dL∗/dt. When using a larger value of w that is 1.6 times that calculated by Eq. (23), the model fits both the trend and magnitude of the period and RMS of the experimental results under conditions producing periodic STW (Fig. 4a, b, solid lines). However, the model still overestimates the period and RMS, especially under non-STW conditions. This discrepancy may be explained by our choice to disregard a layered structure by assuming only one large liquid slug, L∗ (Fig. 7a), exists. The period of pressure change is better correlated with successive reconstruction and/or burst cycles of the layered structure (Fig. 6b).

Numerical results with random initial conditions for each cycle. a Periodic pressure cycle with constant initial conditions. b Initial liquid slug length varied in the range 0.1–1.0 mm. c Liquid slug growth rate varied by setting 1–5 times larger value of w for 0.5 s after 2 s from the beginning of each cycle. d Slug reconstruction site varied in the range 0–180 mm from the bottom of the pipe assuming halfway reconstruction

Nonperiodic STW

Our model cannot explain nonperiodic STW (Figs. 3e and 6c) as each cycle is assumed to start with the same initial values. Figure 6c (e.g., t = 74 – 75 s) shows slug reconstruction within the middle of the pipe (hereafter termed “halfway reconstruction”), which is only observed during nonperiodic STW. We infer that large surface disturbances, resulting from violent liquid slug membrane rupturing under large Qin, grow rapidly and induce halfway reconstruction.

Figure 9b–d shows the waveforms and periodicities with variable initial conditions among different cycles. STW cycles are stable provided that new liquid slugs are reproduced at the bottom of the pipe, irrespective of variations in their initial lengths and growth rates (Fig. 9b, c). However, variation in the slug reconstruction site has a significant effect on the amplitude and periodicity of the signal, generating pressure change waveforms similar to nonperiodic STW (Fig. 9d), as observed in the experiment (Fig. 6c). To determine the mechanism that controls the initial conditions, we will conduct additional experiments with higher-resolution images of flow during future work.

Discussion

Model comparisons

Here we describe the mathematical similarities and differences between our system and existing models (Ida 1996; Wylie et al. 1999; Barmin et al. 2002; Nakanishi and Koyaguchi 2008; Chen et al. 2018) of flow-induced volcanic oscillations (Tables 2 and 3). All of these models have similar pressure change mechanisms (coupling between elastic capacitance and variable flow resistance). Pressure change in the gas chamber could be equated to that in a magma chamber, and variable effective viscosity due to liquid slug length change is comparable with viscosity change during conduit flow (Table 3(a)). When we regard the gas flow part of slug flow as a low-viscosity region, the model of Nakanishi and Koyaguchi (2008) is the most similar existing model (hereafter denoted as the NK model) to our experimental model (Table 3(b)) in terms of the representation of effective viscosity. The NK model simplified the model of Barmin et al. (2002), which includes the kinetics for crystal growth and a significant increase in viscosity depending on crystal content (Fig. 7d), by introducing a characteristic timescale t∗ of viscosity increase. More specifically, t∗ is defined as the time over which the viscosity of the fluid ascending through the conduit increases due to crystallization. The length of the high-viscosity region corresponds to the liquid slug length. In our model, density varies as a function of L∗, which may also cause pressure fluctuations (e.g., Kozono and Koyaguchi 2012); however, the NK model did not include this effect.

The dimensionless parameters \( {Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime } \), G, μ′, and \( {t}_{\mathrm{c}}^{\prime } \) in our experimental model are equivalent to \( {Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime } \), GN, \( {\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime } \), and \( {t}_{\ast}^{\prime } \) in models used to approximate natural volcanic systems, respectively (see Tables 1 and 2 for their definitions). Parameter \( {t}_{\mathrm{c}}^{\prime } \) is a dimensionless characteristic time for slug reconstruction, defined using tc = L∗i/(Aw) and \( {t}_{\mathrm{c}}^{\prime }={t}_{\mathrm{c}}/{T}_{\mathrm{u}} \). Parameter \( {Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime } \) is the dimensionless influx to the magma chamber, GN is the ratio of magmastatic pressure (ρvNgLN) to characteristic pressure (PuN), LN is the length of the conduit, and \( {\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime } \) is the ratio of high to low viscosity, as defined by Barmin et al. (2002) and used in the NK model. Parameters \( {Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime } \) and GN are common in existing models (e.g., Ida 1996; Wylie et al. 1999; Barmin et al. 2002; Nakanishi and Koyaguchi 2008; Chen et al. 2018).

The \( {\mu}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime } \) term has a physical meaning in our experiment, representing the ratio of pressure loss due to viscous resistance in the pipe to the pressure change due to elastic capacitance. It is equivalent to \( {\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime }=8{\mu}_2{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}{V}_{\mathrm{N}}/\left({\pi}^2{a}_{\mathrm{N}}^6\gamma \right) \) in the NK model, where μ2 is the viscosity after crystallization, QinN is the influx to the chamber, VN is the chamber volume, aN is the radius of the conduit, and γ is the effective volumetric modulus of the chamber (Table 2). Considering that the loss of pressure is mainly caused by the high-viscosity part, \( {Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime } \) and \( {Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime } \) are multiplied by the corresponding viscosity ratio in comparison. Using the values listed in Table 2, we estimate the range in values for \( {\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime } \) as 10−8 – 104 which is consistent with the range in our experiment (\( {\mu}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime}\sim {10}^{-1}\hbox{--} {10}^0 \)).

The NK model assumes a contrast in viscosity before and after crystallization of \( {\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime}\sim {10}^1\hbox{--} {10}^3 \). In our experiment, μ′ was much larger than \( {\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime } \) and the contribution of the lower viscosity was negligible. This explains why the STW features in our system are sharper than those in the NK model.

In our model, we determined the relative importance of the effect of gravity and viscous flow resistance (using the higher viscosity) using \( G/\left({\mu}^{\prime }\ {Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime}\right)\sim {10}^{-1}-{10}^0 \). This value lies within the range of \( {G}_{\mathrm{N}}/\left({\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime }\ {Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime}\right)={G}_{\mathrm{N}}/\left({\mu}_{\mathrm{N}}^{\prime }\ {Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime}\right)\sim {10}^{-1}-{10}^3 \) in the NK model, where ρN is magma density (Table 2). The values of these parameters suggest that gravity will affect the pressure change within the chamber if a change in fluid density occurs. When the viscosity is low, the gravity effect becomes dominant, namely, density change may play a role in controlling the oscillations (Kozono and Koyaguchi 2012).

In the NK model, the parameter \( {t}_{\ast}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime }={t}_{\ast }{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}/\left(\pi {a}_{\mathrm{N}}^2{L}_{\mathrm{N}}\right) \) represents the ratio of the timescale of viscosity change to the time during which fluid flows through the conduit, and determines whether pressure oscillations occur. We assume that tc corresponds to the timescale (t∗) because both represent the timescale of the change from low-viscosity flow (i.e., annular in our experiment) to high-viscosity flow (i.e., slug flow). In the NK model, \( {t}_{\ast}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime } \) has an upper and lower limit for oscillations to occur. For the upper limit condition, \( {t}_{\ast}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime }<1 \) must be satisfied, as an increase in viscosity occurs within the conduit. Correspondingly, our model yields \( {t}_{\mathrm{c}}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime}\sim {10}^{-2}\hbox{--} {10}^{-1} \). In our model, we disregard the shear stress on the inner surface during downward film flow to allow slug reconstruction. If we increased \( {t}_{\mathrm{c}}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{in}}^{\prime } \) with increasing Qin, flow within the pipe would occur as a churn or co-current annular flow. However, as we focus on the range of Qin where STW are observed, we did not study the physical processes occurring at such large Qin. In the present study, we observe nonperiodic behavior at the upper range of the chosen Qin values. Below the lower limit of \( {t}_{\ast}^{\prime }{Q}_{\mathrm{inN}}^{\prime } \) in the NK model, flow in the conduit achieves steady state. In contrast, our system does not achieve steady state, irrespective of the value of \( {t}_{\mathrm{c}}^{\prime }{Q}_{in}^{\prime } \), when Qin > 0 and L∗ > 0 (Table 3(c)).

In summary, the lumped parameter model enables us to compare our experimental system with models of flow-induced pressure oscillations in volcanoes. Even if the flow structures appear different, the mechanisms responsible for oscillation may be described by the same mathematical model, using dimensionless parameters in ranges that span within the possible variations in natural volcanic systems.

Cyclic behavior due to flow pattern transitions

In terms of mathematical structures, our experimental system is similar to the models of flow-induced pressure oscillations during dome-building eruptions. These models however do not explicitly include flow pattern transitions, though some of them (Melnik and Sparks 2005; Kozono and Koyaguchi 2012) interpret rapid deflation phases with high-discharge rates as explosive phases. On the other hand, flow pattern transitions (i.e., slug-to-annular and annular-to-slug transitions) are essential for the cyclic behavior in our system. Therefore, the behavior of our experimental system is more similar to repetitive explosive eruptions than to the systems which do not include flow pattern transitions (Ida 1996; Wylie et al. 1999; Barmin et al. 2002; Nakanishi and Koyaguchi 2008; Chen et al. 2018).

The observed slug-to-annular flow transition may correspond to transition from a pressure-building stage to explosive stage through fragmentation (Fig. 10). The observed annular-to-slug flow transition may correspond to the termination of an explosive eruption and preparation for the next cycle (Fig. 10); however, this process is poorly understood (Koyaguchi 2016). Numerical simulations suggest that during fragmentation at depth, dykes may deform or collapse due to a large pressure differences between the flow within the dyke and the surrounding rocks (Dobran 1992; Costa et al. 2009). In addition, fall-back of ejected pyroclasts may clog vents after Vulcanian and Strombolian eruptions (Patrick et al. 2007; Capponi et al. 2016). Vent closure or clogging in natural volcanic systems may be equivalent to slug reconstruction in our experiment, because both are processes that return the system to a pressure-building stage. Based on field observations, textural and geochemical analyses of ejected pyroclasts, and laboratory experiments (Patrick et al. 2007; Gurioli et al. 2014; Del Bello et al. 2015; Capponi et al. 2016; Gaudin et al. 2017), the fall-back of ejected materials is assumed to affect the explosivity of the next eruptive cycle for basaltic eruptions. Fall-back of ejected material is also assumed to occur during co-Plinian fountain of andesitic explosive eruptions (Yasui et al. 2013; Mujin et al. 2017). Such fall-back may be regarded as a kind of “downward flow.”

In our experiment, disturbances in downward flow grow to halfway liquid slug reconstructions (Fig. 6c), which are shown to affect the periodicity by numerical calculation (Fig. 9b–d). Therefore, our experimental results indicate that “downward flow” within the conduit could interact with ascending flow and modulate the explosivity and periodicity of an eruption. When the termination states the same as the initial state of the cycle (Fig. 10b), the period remains constant; however, a strong explosion could disturb the termination state (Fig. 10b which would result in nonperiodic behavior.

Conclusions

Controlled experiments were conducted on gas and liquid flow in a pipe connected to a gas chamber. Under relatively large Qin and Vc, periodic STW is observed, which consists of gradual pressure increase during slug flow and abrupt pressure drop at the slug-to-annular flow transition. Under small Qin and Vc, only slug flow with non-STW features is observed. With a far larger Qin, the periodicity of STW is lost and we observe large surface disturbances on downward film flow causing slug reconstruction at varying locations along the pipe. Experimental movies for these conditions are provided.

A mathematical model of the experimental system and its numerical solutions reveal the mechanisms of the experimental observations. The coupling between elastic capacitance and variable flow resistance is the main factor that generates the STW feature. Fluctuations in the location of the liquid slug reconstruction at each annular-to-slug flow transition have the marked effect in breaking periodicity.

Models of flow-induced volcanic oscillations are mathematically similar to our model, and our gas chamber is equivalent to a magma chamber in terms of an elastic capacitance. Regarding the flow viscosity, the length change of the liquid slug corresponds to the length change of the high-viscosity crystallized region in the dome-building eruption model of Nakanishi and Koyaguchi (2008). The ranges of the dimensionless model parameters for the experiments fall within those for the dome-building eruptions. Considering the essential roles of flow pattern transitions, the behavior of our experiment is more similar to repetitive explosive eruptions than to the nonexplosive dome-building models which do not include flow pattern transitions. Our study implies that “downward flow” in the conduit may interact with the ascending flow and modulate the explosivity and periodicity of the eruption. We can thus make use of this experimental system for understanding periodic and nonperiodic behavior during flow-induced oscillations in volcanic systems.

This study was inspired by the syrup eruption experiment conducted during an outreach activity. The results of this study also strengthen the educational outreach value of the simple experiment in Fig. 1. The experiment allows a clear understanding and active illustration of dynamical systems highlighting the importance of conduit–chamber geometry and flow pattern transitions for oscillatory behaviors (e.g., geodetic signals and eruption cycles) and possible effects of “downward flow” for disturbing eruption periodicity.

References

Anderson K, Lisowski M, Segall P (2010) Cyclic ground tilt associated with the 2004–2008 eruption of Mount St Helens. J Geophys Res 115:B11201. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JB007102

Azzopardi BJ, Pioli L, Abdulkareem LA (2014) The properties of large bubbles rising in very viscous liquids in vertical columns. Int J Multiph Flow 67:160–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2014.08.013

Barmin A, Melnik O, Sparks RSJ (2002) Periodic behavior in lava dome eruptions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 199:173–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00557-5

Batchelor GK (1967) An introduction to fluid dynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Del Bello E, Lane SJ, James MR, Llewellin EW, Taddeucci J, Scarlato P, Capponi A (2015) Viscous plugging can enhance and modulate explosivity of Strombolian eruptions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 423:210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.04.034

Capponi A, Taddeucci J, Scarlato P, Palladino DM (2016) Recycled ejecta modulating Strombolian explosions. Bull Volcanol 78(2):13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-016-1001-z

Chen C, Huang H, Hautmann S, Sacks IS, Linde AT, Taira T (2018) Resonance oscillations of the Soufrière Hills volcano (Montserrat, W.I.) magmatic system induced by forced magma flow from the reservoir into the upper plumbing dike. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 350:7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2017.11.020

Coffey T (2008) Soda pop fizz-ics. Phys Teach 46(8):473–476. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.2999062

Costa A, Sparks RSJ, Macedonio G, Melnik O (2009) Effects of wall-rock elasticity on magma flow in dykes during explosive eruptions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 288(3–4):455–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.10.006

De’ Michieli Vitturi M, Clarke AB, Neri A, Voight B (2013) Extrusion cycles during dome-building eruptions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 371–372:37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.03.037

Deus HM, Bolacha E, Vasconcelos C, Fonseca PE (2011) Analogue modelling to understand geological phenomena. Proceedings of the GeoSciEd VI, Johannesburg

Dobran F (1992) Nonequilibrium flow in volcanic conduits and application to the eruptions of Mt. St. Helens on May 18, 1980, and Vesuvius in AD 79. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 49(3–4):285–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(92)90019-A

Den Doelder CFJ, Koopmans RJ, Molenaar J, Van de Ven AAF (1998) Comparing the wall slip and the constitutive approach for modelling spurt instabilities in polymer melt flows. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech 75(1):25–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0257(97)00081-5

Druitt TH, Young SR, Baptie B, Bonadonna C, Calder ES, ab C, Cole PD, Harford CL et al (2002) Episodes of cyclic Vulcanian explosive activity with fountain collapse at Soufrière Hills volcano, Montserrat. Geol Soc London, Mem 21:281–306. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.MEM.2002.021.01.13

Fontaine FR, Roult G, Michon L, Barruol G, Di Muro A (2014) The 2007 eruptions and caldera collapse of the Piton de La Fournaise volcano (La Réunion Island) from tilt analysis at a single very broadband seismic station. Fabrice Geophys Res Lett 41:2803–2811. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059691

Fujita E, Ukawa M, Yamamoto E (2004) Subsurface cyclic magma sill expansions in the 2000 Miyakejima volcano eruption: possibility of two-phase flow oscillation. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 109(B4). https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JB002556

Fukuyama E (1988) Saw-teeth-shaped tilt change associated with volcanic tremor at the Izu-Oshima volcano. J Volcanol Soc Jpn 33:S128–S135

Gaudin D, Taddeucci J, Scarlato P, del Bello E, Ricci T, Orr T, Houghton B, Harris A et al (2017) Integrating puffing and explosions in a general scheme for Strombolian-style activity. J Geophys Res Solid Earth:1860–1875. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JB013707

Genco R, Ripepe M (2010) Inflation-deflation cycles revealed by tilt and seismic records at Stromboli volcano. Geophys Res Lett 37(12). https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL042925

Genco R, Ripepe M, Marchetti E, Bonadonna C, Biass S (2014) Acoustic wavefield and Mach wave radiation of flashing arcs in Strombolian explosion measured by image luminance. Geophys Res Lett 41(20):7135–7142. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL061597

Gurioli L, Colo’ L, Bollasina AJ, Harris AJL, Whittington A, Ripepe M (2014) Dynamics of Strombolian explosions: inferences from field and laboratory studies of erupted bombs from Stromboli volcano. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 119(1):319–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JB010355

Hewitt GF, Hall-Taylor NS (1970) Annular two-phase flow. Pergamon, Oxford

Ida Y (1996) Cyclic fluid effusion accompanied by pressure change: implication for volcanic eruptions and tremor. Geophys Res Lett 23(12):1457–1460. https://doi.org/10.1029/96GL01325

Iga K, Kimura R (2007) Convection driven by collective buoyancy of microbubbles. Fluid Dyn Res 39(1–3):68–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fluiddyn.2006.08.003

Iguchi M, Yakiwara H, Tameguri T, Hendrasto M, Hirabayashi J (2008) Mechanism of explosive eruption revealed by geophysical observations at the Sakurajima, Suwanosejima and Semeru volcanoes. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 178(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2007.10.010

Iverson RM, Dzurisin D, Gardner CA, Gerlach TM, LaHusen RG, Lisowski M, Major Jon J, Malone SD et al (2006) Dynamics of seismogenic volcanic extrusion at Mount St Helens in 2004–05. Nature 444(7118):439–443. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05322

James MR, Lane SJ, Chouet B, Gilbert JS (2004) Pressure changes associated with the ascent and bursting of gas slugs in liquid-filled vertical and inclined conduits. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 129(1–3):61–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0273(03)00232-4

James MR, Lane SJ, Chouet BA (2006) Gas slug ascent through changes in conduit diameter: laboratory insights into a volcano-seismic source process in low-viscosity magmas. J Geophys Res 111. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JB003718

Jaupart C, Vergniolle S (1989) The generation and collapse of a foam layer at the roof of a basaltic magma chamber. J Fluid Mech 203:347. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089001497

Koyaguchi T (2016) Physical phenomena of volcanic eruptions and magma ascent: towards forecasting volcanic eruption sequence based on physical models and field observations. Bull Volcanol Soc Japan 61(1):37–68

Kozono T, Koyaguchi T (2012) Effects of gas escape and crystallization on the complexity of conduit flow dynamics during lava dome eruptions. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 117(8):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JB009343

Kumagai I, Davaille A, Kurita K, Stutzmann E (2008) Mantle plumes: thin, fat, successful, or failing? Constraints to explain hot spot volcanism through time and space. Geophys Res Lett 35(16):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035079

Kurita K, Kumagai I, Davaille A (2008) An invitation to kitchen earth sciences, an example of MISO soup convection experiment in classroom. Am Geophys Union, Fall Meet. 2008, San Francisco

Kurokawa A (2016) Understanding oscillation phenomena induced by non-linear magma rheology. PhD thesis, Univ. Tokyo, Japan

Lane SJ, Phillips JC, Ryan GA (2008) Dome-building eruptions: insights from analogue experiments. Geol Soc London, Spec Publ 307(1):207–237. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP307.12

Mader HM, Manga M, Koyaguchi T (2004) The role of laboratory experiments in volcanology. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 129:1–3):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0273(03)00228-2

Maeda I (2000) Nonlinear visco-elastic volcanic model and its application to the recent eruption of Mt. Unzen. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 95(1–4):35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00120-1

Melnik O, Sparks RSJ (2005) Controls on conduit magma flow dynamics during lava dome building eruptions. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 110(B2):B02209. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JB003183

Mujin M, Nakamura M, Miyake A (2017) Eruption style and crystal size distributions: crystallization of groundmass nanolites in the 2011 Shinmoedake eruption. Am Mineral 102(2014):2367–2380. https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2017-6052CCBYNCND

Nakanishi M, Koyaguchi T (2008) A stability analysis of a conduit flow model for lava dome eruptions. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 178(1):46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.01.011

Nishimura T, Ichihara M, Ueki S (2006) Investigation of the Onikobe Geyser, NE Japan, by observing the ground tilt and flow parameters. Earth Planets Sp 58(6):e21–e24. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03351967

Ohminato T, Chouet BA, Dawson P, Kedar S (1998) Waveform inversion of very long period impulsive signals associated with magmatic injection beneath Kilauea volcano, Hawaii. J Geophys Res 103:23,839–23,862. https://doi.org/10.1029/98JB01122

Ozawa M, Nakanishi S, Ishigai S, Mizuta Y, Tarui H (1979) Flow instabilities in boiling channels: part 1 pressure drop oscillation. Bull JSME 22(170):1113–1118. https://doi.org/10.1299/jsme1958.22.1113

Patrick MR, Harris AJL, Ripepe M, Dehn J, Rothery DA, Calvari S (2007) Strombolian explosive styles and source conditions: insights from thermal (FLIR) video. Bull Volcanol 69(7):769–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-006-0107-0

Pioli L, Azzopardi BJ, Bonadonna C, Brunet M, Kurokawa AK (2017) Outgassing and eruption of basaltic magmas: the effect of conduit geometry. Geology 45(8):G38787.1. https://doi.org/10.1130/G38787.1

Scott DR, Stevenson DJ, Whitehead JA (1986) Observations of solitary waves in a viscously deformable pipe. Nature 319(6056):759–761. https://doi.org/10.1038/319759a0

Takeo M, Maehara Y, Ichihara M, Ohminato T, Kamata R, Oikawa J (2013) Ground deformation cycles in a magma-effusive stage, and sub-Plinian and Vulcanian eruptions at Kirishima volcanoes, Japan. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 118(9):4758–4773. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50278

Vergniolle S, Jaupart C (1986) Separated two-phase flow and basaltic eruptions. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 91(B12):12842–12860. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB091iB12p12842

Voight B, Hoblitt RP, Clarke AB, Miller A, Lynch L, Mcmahon J (1998) Remarkable cyclic ground deformation monitored in real-time on Montserrat, and its use in eruption forecasting. Geophys Res Lett 25(18):3405–3408. https://doi.org/10.1029/98GL01160

Wallis GB (1969) One-dimensional two-phase flow. McGraw-Hill, New York

Whitehead JA, Helfrich KR (1991) Instability of flow with temperature-dependent viscosity: a model of magma dynamics. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 96(B3):4145–4155. https://doi.org/10.1029/90JB02342

Woods AW, Koyaguchi T (1994) Transitions between explosive and effusive eruptions of silicic magmas. Nature 370(6491):641–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/370641a0

Wylie JJ, Voight B, Whitehead JA (1999) Instability of magma flow from volatile-dependent viscosity. Science 285(5435):1883–1885. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5435.1883

Yasui M, Takahashi M, Shimada J, Miki D, Ishihara K (2013) Comparative study of proximal eruptive events in the large-scale eruptions of Sakurajima volcano: An-Ei eruption vs. Taisho eruption. Bull Volcanol Soc Jpn 58(1):59–76. https://doi.org/10.18940/kazan.58.1_59

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank M. Ripepe, V. Vidal, K. Kurita, and O. Kuwano for useful comments that improved the experimental system and model. The original syrup eruption experiment was designed by S. Takeuchi and introduced to the authors by A. Namiki. The manuscript has been significantly improved by constructive comments by the two anonymous reviewers and the associate editor (L. Pioli) and thorough check by the executive editor (A. Harris).

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant No. 15K13561 and JSPS Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow No. 16J06324.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editorial responsibility: L. Pioli

Appendix

Appendix

The role of surface tension

In the experiments, the uppermost liquid slug becomes a thin film membrane that supports ~ 1 kPa prior to the slug-to-annular flow transition. According to the experimental movie (Movie 1), the film membrane bulges upward immediately before the rupture (Fig. 11a). It is inferred that this pressure difference, Δp, across a liquid slug is supported by surface tension, which is given by

where γs is the surface tension of the liquid, and Rup and Rbt are the radii of curvature of the top and bottom of the liquid slug, respectively. Both Rup and Rbt are positive when the liquid slug surface bulges upward (Fig. 11b). The constitutive equations for Rup and Rbt are obtained as a function of Q and L∗ by analysis of images of an ascending liquid slug (Fig. 5b). When estimating Δp, we analyzed the curvature of only the uppermost liquid slugs, because the following liquid slugs are flatter and provide only a minor contribution.

a Sequential photographs of the uppermost liquid slug. The liquid slug becomes a film membrane (8.24 s) immediately before film rupture. The shapes of the top and bottom surfaces of the liquid slug (red and yellow points, respectively) are captured at 10 points. b For the upper and bottom surfaces, three points (up1–3 and bt1–3, respectively) are determined by averaging the positions of red and yellow points captured by image analysis (see a): the left 3 points for up1 and bt1, middle 4 for up2 and bt2, and right 3 for up3 and bt3, respectively. Angles are represented by θup and θbt, defined as θ > 180° when the surface is convex downward, and θ < 180° when the surface is convex upward. Curvatures are defined as Rup, bt = R′r tan(θup, bt/2), where R′ is the correction factor (R′ = 0.27). We assume that the upper part of the gas slug is hemispherical when ascending at a constant velocity (Batchelor 1967), and L∗ is the total length of the liquid slug in the pipe. c Changes in Rup and Rbt over time. d Least-squares fit to the calculated Δp yields the empirical relationship Δ p = − 1.11 × 106 (L∗ − Lc)Q/πa2 + 113

Details of the image analysis are explained in the caption to Fig. 11. A decrease in the radius of curvature as the liquid slug ascends is demonstrated in Fig. 11a–c. We find that Δp (Eq. 2) has a linear relationship with −(L∗ − Lc)Q/πa2 and is reasonably well-fitted by Eq. (5). An intercept for the fitting parameter vanishes by differentiating Eq. (5) and does not affect the solution. Therefore, it is omitted in Eq. (5).

Downward film flow

When x < Hw, Hw descends along the pipe. Under this condition, Hw is given by

where Hwi and Hmax are the values of Hw for L∗ = L∗i and L∗ = 0, respectively, and w (< 0) is the average velocity of the downward film flow. Assuming laminar flow driven by gravity, w is given as follows:

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanno, Y., Ichihara, M. Sawtooth wave-like pressure changes in a syrup eruption experiment: implications for periodic and nonperiodic volcanic oscillations. Bull Volcanol 80, 65 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-018-1227-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-018-1227-z