Abstract

Purpose

After progression to immunotherapy, the standard of care for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was limited. Administration of the same or different immune checkpoint inhibitors (i.e., ICI rechallenge) may serve as a novel option. The present study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of ICI rechallenge for NSCLC and explore prognostic factors.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, data of advanced or metastatic NSCLC patients rechallenged with ICI at the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Peking Union Medical College between December 2018 and June 2021 were retrieved. Progression-free, overall survivals (PFS; OS), etc. were calculated. Subgroup analyses were conducted according to baseline characteristics, prior treatment results, etc. for prognostic factor exploration using the Cox model.

Results

Forty patients were included. Median age was 59 years. Thirty-one (78%) were male. Twenty-seven (68%) were smokers. Adenocarcinoma (28 [70%]) was the major histological subtype. Median PFS of patients receiving initial ICI was 5.7 months. The most common rechallenge regimens were ICI plus chemotherapy and/or angiogenesis inhibitor (93%). Seventeen (43%) were rechallenged with another ICI. Median PFS for ICI rechallenge was 6.8 months (95% CI 5.8–7.8). OS was immature. Tendencies for longer PFS were observed in nonsmoker or patients with adenocarcinoma, response of stable/progressive disease in initial immunotherapy, or whose treatment lines prior to ICI rechallenge were one/two. However, all results of prognostic factors were nonsignificant.

Conclusion

ICI rechallenge may be an option for NSCLC after progress to immunotherapy. Further studies to confirm the efficacy and investigate prognostic factors are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide (Bray et al. 2018). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the major histological type, accounting for almost 85% of lung cancer cases (Chen et al. 2014). When diagnosed as NSCLC, nearly 70% patients were with advanced or metastatic disease (Molina et al. 2008). For advanced or metastatic NSCLC with negative driver gene, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) with or without chemotherapy were recommended ("NCCN" 2021). However, after progression, the standard of care is only chemotherapy. Novel regimens are worthy to be explored.

After progression to ICI, administration of the same or different ICI (i.e., ICI rechallenge) may serve as a novel treatment option. Several secondary analyses of clinical trials and a case report have demonstrated the potential efficacy of ICI rechallenge in advanced melanoma (Beaver et al. 2018; Long et al. 2017) and renal cell carcinoma (Escudier et al. 2017; George et al. 2016; Rebuzzi et al. 2018). In terms of rechallenge with the same ICI (defined as the ICI used for rechallenge was the same as the one for the initial immunotherapy) in NSCLC, a retrospective analysis of the phase III OAK study indicated that patients received atezolizumab treatment beyond progression (TBP) had numerically longer median overall survival (OS) (Gandara et al. 2018). The OS in atezolizumab TBP arm, other anticancer treatment arm, and no anticancer treatment arm were 12.7 months vs 8.8 months vs 2.2 months, respectively. Four real-world studies in China, Europe, and USA (Ge et al. 2020; Metro et al. 2019; Ricciuti et al. 2019; Stinchcombe et al. 2020) and a case report (Ito et al. 2020) also showed promising antitumor activity of rechallenge with the same ICI. Although data of patients rechallenged with different ICI were limited, encouraging benefit was observed in a case series (Fujita et al. 2018). In the case series (Fujita et al. 2018), 12 patients previously treated with nivolumab were rechallenged with pembrolizumab. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.1 months.

The present retrospective cohort study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of ICI rechallenge for NSCLC and explore prognostic factors. It provided new evidence of later-line treatment after progression to ICI.

Methods

Study design and patients

In this retrospective cohort study, advanced or metastatic NSCLC patients rechallenged with ICI (whether rechallenge with the same ICI or not) at the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Peking Union Medical College between December 2018 and June 2021 were included for analysis. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (approval number: 21/323-2994). Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Patients aged 18–75 years; with advanced or metastatic NSCLC and at least target lesion; rechallenged with single-agent ICI or ICI plus chemotherapy and (or) angiogenesis inhibitor after initial immunotherapy were eligible. Only those who discontinued initial ICI due to disease progression and rechallenged were included. Those who rechallenged ICI after initial treatment discontinuation by adverse events, those who received initial ICI as adjuvant or maintenance therapy, and those had no response evaluation after ICI rechallenge were excluded.

Study assessment

Demographic and baseline characteristics, and data of tumor treatment were retrieved from the health information system, including age, sex, smoking status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), tumor TNM stage, histological subtype, data of initial immunotherapy and ICI rechallenge, etc.

Efficacy end points were PFS (defined as the time from study treatment initiation to disease progression or death from any cause) per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) 1.1, OS (defined as the time from study treatment initiation to death from any cause), overall response rate (ORR; defined as the proportion of patients with complete response [CR] or partial response [PR]), and disease control rate (DCR; defined as the proportion of patients with CR, PR or stable disease [SD]) for ICI rechallenge.

Statistical considerations

The continuous and categorical data were presented as medians [quartile 1 (Q1) and quartile 3 (Q3)] and numbers (percentages), respectively. Median PFS and OS and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Subgroup analyses for efficacy predictors were conducted based on smoking status (nonsmoker vs smoker), ECOG PS (≥ 2 vs 0–1), histological subtypes (squamous carcinoma vs adenocarcinoma), best overall response (BOR; SD/progressive disease [PD] vs CR/PR), treatment lines prior to ICI rechallenge (≥ three vs one/two), rechallenge with the same ICI (no vs yes), ICI rechallenge regimens (ICI plus chemotherapy vs ICI plus angiogenesis inhibitor vs ICI plus chemotherapy and angiogenesis inhibitor vs monotherapy), brain, liver, or bone metastases (yes vs no), programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) tumor proportion score (TPS; < 1% vs ≥ 1%), and positive driver genes (EGFR vs KRAS vs HER2 vs wildtype). Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

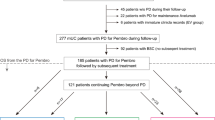

Forty patients rechallenged with ICI between December 2018 and June 2021 were included. Median follow-up was 8.0 months (IQR 7.9–8.5 months). Median age was 59 years (IQR 55–65 years). Thirty-one patients (78%) were male. Twenty-seven (68%) were smokers. Twenty-nine (73%) had ECOG PS of 0 or 1. Adenocarcinoma (28 [70%]) was the major histological subtype, and one adenosquamous carcinoma (3%) was also included. At diagnosis, most patients (29 [73%]) were at stage IV. Driver genes were tested in 30 patients, of which 17 (57%) were positive. PD-L1 data were available in 15 patients. Eight and seven (53%; 47%) were with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1% and < 1%, respectively (Table 1).

In reference to the initial immunotherapy, most patients (21 [53%]) had received immunotherapy plus chemotherapy. Median PFS was 5.7 months (95% CI 4.1–7.2 months). Fourteen (35%), nineteen (48%), and seven (18%) had achieved PR, SD, and PD, respectively. After progression to the first immunotherapy, the majority of patients (33 [83%]) were directly rechallenged with ICI. Three (8%) received targeted therapy and four (10%) received chemotherapy between two lines of immunotherapy. Treatment lines prior to ICI rechallenge were one in 17 patients (43%), two in 12 (30%), and ≥ three in 11 (28%). The most common rechallenge regimens were ICI plus chemotherapy and (or) angiogenesis inhibitor (37 [93%]). And 17 patients (43%) were rechallenged with another ICI (Table 2).

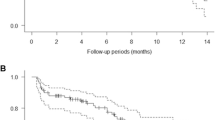

During follow-up, 26 cases (65%) of progression occurred and eight patients (20%) died. Median PFS was 6.8 months (95% CI 5.8–7.8 months; Fig. 1). OS data were immature. Nine patients (22.5%) achieved PR. SD was observed in 25 cases (62.5%). ORR was 22.5% and DCR was 85% (Table 3).

For subgroup analyses, tendencies for longer PFS were observed in nonsmoker or patients with adenocarcinoma, with BOR of SD/PD in initial immunotherapy, or whose treatment lines prior to ICI rechallenge were one/two. However, all HR between these subgroups were nonsignificant (Fig. 2 and 3). ECOG PS, rechallenge with the same ICI or not, ICI rechallenge regimens, metastatic sites, PD-L1 TPS, and driver genes did not affect PFS, either (Figs. 2, 3, S1 and S2).

Kaplan–Meier curve of progression-free survival in patients with different smoking status (A), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (B; ECOG PS), histological type (C), response to initial immunotherapy (D), previous treatment lines (E), rechallenge regimens (F), and the same immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge or not (G). ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor

Forest plot of progression-free survival in patients with different smoking status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), histological type, response to initial immunotherapy, previous treatment lines, rechallenge regimens, and the same immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge or not. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor. *One adenosquamous carcinoma was excluded from analyses

Discussion

Treatment after progression to ICI in NSCLC is limited. Some studies indicated ICI rechallenge might be a potential option (Fujita et al. 2018; Gandara et al. 2018; Metro et al. 2019; Ricciuti et al. 2019; Stinchcombe et al. 2020). Interestingly, in the present study, median PFS of initial immunotherapy was 5.8 months, while that of ICI rechallenge was 6.8 months. On one hand, the overall median PFS with initial immunotherapy may be influenced by some patients with early resistance. In our study, seven patients developed PD after only two cycles of immunotherapy-based therapy, which may be due to the early resistance to the combined agents rather than ICI. Previous studies showed a delayed onset of action of ICIs with a median time to response of 2.05–3.3 months (Chen et al. 2021; Hida et al. 2017; Rizvi et al. 2015). After re-administration of ICI and change of the combined regimens, these patients responded well. On the other hand, the contradictory results may be because of different ICI combination regimens in the two lines of immunotherapy. Compared with initial immunotherapy, ICI rechallenge regimens consisted of less monotherapy and ICI plus chemotherapy, and more ICI plus angiogenesis inhibitor with or without chemotherapy. ICI and anti-angiogenic agents have synergistic effect. As a critical angiogenic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can repolarize tumor-associated macrophages to M2-like phenotypes (Fukumura et al. 2018), inhibit the maturation of dendritic cells (Gabrilovich et al. 1996), promote regulatory T-cell infiltration (Fukumura et al. 2018), and induce CD8+ T-cell exhaustion (Kim et al. 2019), and thus can lead to immune suppression and reduce effectiveness of ICI. Clinical studies also showed the efficacy of ICI plus VEGF inhibitors (Neal et al. 2020; Seto et al. 2020; Socinski et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2020). Thus, additional VEGF inhibitor may bring benefit to ICI rechallenge. However, the findings should be confirmed by further studies.

Currently, the effectiveness of ICI rechallenge remains controversial. Some studies showed NSCLC diseases resistant to initial ICI therapies might display limited responses to ICI rechallenge, and might confer clinical benefits only in a small fraction, with the ORR of 0–8.5%, median PFS of 1.5–2.9 months, and median OS of 6.5–11.0 months (Fujita et al. 2019; Katayama et al. 2019; Teraoka et al. 2021; Watanabe et al. 2019); whereas in additional studies of ICI rechallenge, it was proposed as a potentially feasible option for those who suffered disease progression after initial ICI treatments, with the ORR of 11.6–23.0%, median PFS or duration of treatment of 4.1–9.1 months, and median OS of 9.5–26.6 months (Ge et al. 2020; Inno et al. 2021; Metro et al. 2019; Neal et al. 2020; Ricciuti et al. 2019; Stinchcombe et al. 2020). In the present study, OS data were immature and median follow-up was 8.0 months. Thus, median OS will be longer than 8.0 months. And, other efficacy end points of our study were in the range of the above-mentioned studies. Unlike the previous studies that mainly focused on ICI monotherapy rechallenge after ICI monotherapy (Fujita et al. 2018; Metro et al. 2019; Ricciuti et al. 2019; Stinchcombe et al. 2020), the majority of patients in our study received ICI combined with chemotherapy or anti-angiogenic agents as ICI rechallenge. In this context, the data from our study may provide some insights into future therapeutic strategies for advanced NSCLC.

Efficacy predictor analyses in our study showed no significant results. It may be attributed to the small sample size. The historical data on response to ICI rechallenge in different subgroups were limited. A retrospective cohort study (Ge et al. 2020) reported that males, squamous histology, no brain or liver metastases, any age, not beyond ≥ the third treatment line, with PR to the previous ICI, and monotherapy as previous ICI can benefit more from ICI rechallenge compared with other treatment. For initial immunotherapy, patients with smoking exposure (Kim et al. 2017; Zhao et al. 2021), better ECOG PS (Zhao et al. 2021), higher PD-L1 expression (Duchemann et al. 2021), and absence of liver metastasis (Zhao et al. 2021) benefited more from the treatment. Theoretically, previous treatment lines and response to initial immunotherapy can lead to various efficacy of ICI rechallenge. And rechallenge with the same ICI or not as well as rechallenge regimen may also have different antitumor activity. All above-mentioned potentially prognostic factors of ICI rechallenge should be explored in future prospective studies.

Four trials of ICI rechallenge for NSCLC are ongoing. Two single-arm, phase II trials (NCT04670913 (Xing et al. 2021) and NCT03689855) aimed to assess the efficacy of camrelizumab plus apatinib (VEGF receptor 2 TKI) and atezolizumab plus ramucirumab (anti-VEGF receptor 2 antibody). The remaining two randomized, controlled phase III trials were designed to compared efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus cabozantinib (multitargeted TKI) vs docetaxel (NCT04471428), and pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib vs docetaxel plus lenvatinib (NCT03976375). The results will bring new evidence of ICI rechallenge for NSCLC.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, the biases were inevitable due to the retrospective nature of the study, including selection bias as ICI rechallenge was based on the physician's discretion. Second, the sample size was small and insufficient for efficacy predictor analyses.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that ICI rechallenge may serve as an option for NSCLC patients previously treated with immunotherapy. The efficacy should be confirmed in further investigations.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available on request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Beaver JA, Hazarika M, Mulkey F, Mushti S, Chen H, He K, Sridhara R, Goldberg KB, Chuk MK, Chi D-C, Chang J, Barone A, Balasubramaniam S, Blumenthal GM, Keegan P, Pazdur R, Theoret MR (2018) Patients with melanoma treated with an anti-PD-1 antibody beyond RECIST progression: a US Food and Drug Administration pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol 19:229–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30846-X

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492

Chen Z, Fillmore CM, Hammerman PS, Kim CF, Wong K-K (2014) Non-small-cell lung cancers: a heterogeneous set of diseases. Nat Rev Cancer 14:535–546. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3775

Chen S, Zhang Z, Zheng X, Tao H, Zhang S, Ma J, Liu Z, Wang J, Qian Y, Cui P, Huang D, Huang Z, Wu Z, Hu Y (2021) Response efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 11:562315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.562315

Duchemann B, Remon J, Naigeon M, Cassard L, Jouniaux JM, Boselli L, Grivel J, Auclin E, Desnoyer A, Besse B, Chaput N (2021) Current and future biomarkers for outcomes with immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 10:2937–2954. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-839

Escudier B, Motzer RJ, Sharma P, Wagstaff J, Plimack ER, Hammers HJ, Donskov F, Gurney H, Sosman JA, Zalewski PG, Harmenberg U, McDermott DF, Choueiri TK, Richardet M, Tomita Y, Ravaud A, Doan J, Zhao H, Hardy H, George S (2017) Treatment beyond progression in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab in CheckMate 025. Eur Urol 72:368–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.037

Fujita K, Uchida N, Kanai O, Okamura M, Nakatani K, Mio T (2018) Retreatment with pembrolizumab in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients previously treated with nivolumab: emerging reports of 12 cases. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 81:1105–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-018-3585-9

Fujita K, Uchida N, Yamamoto Y, Kanai O, Okamura M, Nakatani K, Sawai S, Mio T (2019) Retreatment with anti-PD-L1 antibody in advanced non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with anti-PD-1 antibodies. Anticancer Res 39:3917–3921. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.13543

Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK (2018) Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15:325–340. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29

Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, Cunningham HT, Meny GM, Nadaf S, Kavanaugh D, Carbone DP (1996) Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med 2: 1096–1103. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1096-1096

Gandara DR, von Pawel J, Mazieres J, Sullivan R, Helland Å, Han J-Y, Ponce Aix S, Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Kubo T, Park K, Goldschmidt J, Gandhi M, Yun C, Yu W, Matheny C, He P, Sandler A, Ballinger M, Fehrenbacher L (2018) Atezolizumab treatment beyond progression in advanced NSCLC: results from the randomized, phase III OAK study. J Thorac Oncol 13:1906–1918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.2027

Ge X, Zhang Z, Zhang S, Yuan F, Zhang F, Yan X, Han X, Ma J, Wang L, Tao H, Li X, Zhi X, Huang Z, Hofman P, Prelaj A, Banna GL, Mutti L, Hu Y, Wang J (2020) Immunotherapy beyond progression in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 9:2391–2400. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-1252

George S, Motzer RJ, Hammers HJ, Redman BG, Kuzel TM, Tykodi SS, Plimack ER, Jiang J, Waxman IM, Rini BI (2016) Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated beyond progression: a subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2:1179–1186. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0775

Hida T, Nishio M, Nogami N, Ohe Y, Nokihara H, Sakai H, Satouchi M, Nakagawa K, Takenoyama M, Isobe H, Fujita S, Tanaka H, Minato K, Takahashi T, Maemondo M, Takeda K, Saka H, Goto K, Atagi S, Hirashima T, Sumiyoshi N, Tamura T (2017) Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in Japanese patients with advanced or recurrent squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 108:1000–1006. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13225

Inno A, Roviello G, Ghidini A, Luciani A, Catalano M, Gori S, Petrelli F (2021) Rechallenge of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 165:103434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103434

Ito K, Oguri T, Takeda N, Fukumitsu K, Fukuda S, Kanemitsu Y, Tajiri T, Ohkubo H, Takemura M, Maeno K, Ito Y, Niimi A (2020) A case of non-small cell lung cancer with long-term response after re-challenge with nivolumab. Respir Med Case Rep 29:100979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2019.100979

Katayama Y, Shimamoto T, Yamada T, Takeda T, Yamada T, Shiotsu S, Chihara Y, Hiranuma O, Iwasaku M, Kaneko Y, Uchino J, Takayama K (2019) Retrospective efficacy analysis of immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010102

Kim JH, Kim HS, Kim BJ (2017) Prognostic value of smoking status in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 8:93149–93155. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.18703

Kim CG, Jang M, Kim Y, Leem G, Kim KH, Lee H, Kim T-S, Choi SJ, Kim H-D, Han JW, Kwon M, Kim JH, Lee AJ, Nam SK, Bae S-J, Lee SB, Shin SJ, Park SH, Ahn JB, Jung I, Lee KY, Park S-H, Kim H, Min BS, Shin E-C (2019) VEGF-A drives TOX-dependent T cell exhaustion in anti-PD-1-resistant microsatellite stable colorectal cancers. Sci Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aay0555

Long GV, Weber JS, Larkin J, Atkinson V, Grob J-J, Schadendorf D, Dummer R, Robert C, Márquez-Rodas I, McNeil C, Schmidt H, Briscoe K, Baurain J-F, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD (2017) Nivolumab for patients with advanced melanoma treated beyond progression: analysis of 2 phase 3 clinical trials. JAMA Oncol 3:1511–1519. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1588

Metro G, Addeo A, Signorelli D, Gili A, Economopoulou P, Roila F, Banna G, De Toma A, Rey Cobo J, Camerini A, Christopoulou A, Lo Russo G, Banini M, Galetta D, Jimenez B, Collazo-Lorduy A, Calles A, Baxevanos P, Linardou H, Kosmidis P, Garassino MC, Mountzios G (2019) Outcomes from salvage chemotherapy or pembrolizumab beyond progression with or without local ablative therapies for advanced non-small cell lung cancers with PD-L1 ≥ 50% who progress on first-line immunotherapy: real-world data from a European cohort. J Thorac Dis 11:4972–4981. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.12.23

Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA (2008) Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc 83:584–594. https://doi.org/10.4065/83.5.584

"NCCN" (2021) National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Version 5.2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2021

Neal JW, Lim FL, Felip E, Gentzler RD, Patel SB, Baranda J, Fang B, Squillante CM, Simonelli M, Werneke S, Curran D, Aix SP (2020) Cabozantinib in combination with atezolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients previously treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor: Results from cohort 7 of the COSMIC-021 study. J Clin Oncol 38:9610–9610. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.9610

Rebuzzi SE, Bregni G, Grassi M, Damiani A, Buscaglia M, Buti S, Fornarini G (2018) Immunotherapy beyond progression in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Immunotherapy 10:1123–1132. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2018-0042

Ricciuti B, Genova C, Bassanelli M, De Giglio A, Brambilla M, Metro G, Baglivo S, Dal Bello MG, Ceribelli A, Grossi F, Chiari R (2019) Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated beyond progression. Clin Lung Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2019.02.001

Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, Stinchcombe TE, Dy GK, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Lena H, Minenza E, Mennecier B, Otterson GA, Campos LT, Gandara DR, Levy BP, Nair SG, Zalcman G, Wolf J, Souquet PJ, Baldini E, Cappuzzo F, Chouaid C, Dowlati A, Sanborn R, Lopez-Chavez A, Grohe C, Huber RM, Harbison CT, Baudelet C, Lestini BJ, Ramalingam SS (2015) Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol 16:257–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9

Seto T, Nosaki K, Shimokawa M, Toyozawa R, Sugawara S, Hayashi H, Murakami H, Kato T, Niho S, Saka H, Oki M, Yoshioka H, Okamoto I, Daga H, Azuma K, Tanaka H, Nishino K, Satouchi M, Yamamoto N, Nakagawa K (2020) LBA55 WJOG @Be study: a phase II study of atezolizumab (atez) with bevacizumab (bev) for non-squamous (sq) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with high PD-L1 expression. Ann Oncol 31:S1185–S1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2288

Socinski MA, Mok TS, Nishio M, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Moro-Sibilot D, Thomas CA, Barlesi F, Finley G, Kong S, Liu X, Lee A, Coleman S, Shankar G, Reck M (2020) Abstract CT216: IMpower150 final analysis: Efficacy of atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) and chemotherapy in first-line (1L) metastatic nonsquamous (nsq) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) across key subgroups. Cancer Res 80:CT216. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.Am2020-ct216

Stinchcombe TE, Miksad RA, Gossai A, Griffith SD, Torres AZ (2020) Real-world outcomes for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with a PD-L1 inhibitor beyond progression. Clin Lung Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2020.04.008

Taylor MH, Lee C-H, Makker V, Rasco D, Dutcus CE, Wu J, Stepan DE, Shumaker RC, Motzer RJ (2020) Phase IB/II trial of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, endometrial cancer, and other selected advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 38:1154–1163. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01598

Teraoka S, Akamatsu H, Takamori S, Hayashi H, Miura S, Hata A, Toi Y, Shiraishi Y, Mamesaya N, Sato Y, Furuya N, Koh Y, Yamanaka T, Yamamoto N, Nakagawa K (2021) 1291P A phase II study of nivolumab rechallenge therapy in advanced NSCLC patients who responded to prior anti-PD-1/L1 inhibitors: West Japan Oncology Group 9616L. Ann Oncol 32:S1001–S1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1893

Watanabe H, Kubo T, Ninomiya K, Kudo K, Minami D, Murakami E, Ochi N, Ninomiya T, Harada D, Yasugi M, Ichihara E, Ohashi K, Fujiwara K, Hotta K, Tabata M, Maeda Y, Kiura K (2019) The effect and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 49:762–765. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyz066

Xing P, Wang M, Zhao J, Zhong W, Chi Y, Xu Z, Li J (2021) Study protocol: a single-arm, multicenter, phase II trial of camrelizumab plus apatinib for advanced nonsquamous NSCLC previously treated with first-line immunotherapy. Thorac Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.14113

Zhao Q, Li B, Xu Y, Wang S, Zou B, Yu J, Wang L (2021) Three models that predict the efficacy of immunotherapy in Chinese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.4171

Zhou C, Wang Y, Zhao J, Chen G, Liu Z, Gu K, Huang M, He J, Chen J, Ma Z, Feng J, Shi J, Yu X, Cheng Y, Yao Y, Chen Y, Guo R, Lin X, Wang Z-H, Gao G, Wang QR, Li W, Yang X, Wu L, Zhang J, Ren S (2020) Efficacy and biomarker analysis of camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC previously treated with chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3136

Acknowledgements

We thank Yunjie Yu (former employee) and Yanhua Xu from Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. for the provision of medical writing support.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Peking Union Medical College (approval number: 21/323–2994).

Consent to participate

Informed consent of participants was waived by the ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Hao, X., Yang, K. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 148, 3081–3089 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03901-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03901-2