Abstract

Background

Soluble form suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (sST2) is known to have prognostic value in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and could impact mortality after acute ischemic stroke (AIS). However, before considering sST2 as a therapeutic target, the kinetics of release and its association with adverse clinical events in both STEMI and AIS patients have to be determined.

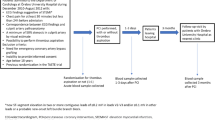

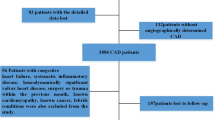

Methods

We prospectively enrolled 251 STEMI patients, treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention, and 152 AIS patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy. We evaluated the level of sST2 in patient sera at five time point (admission, 4, 24, 48 h and 1 month from admission for STEMI patients and admission, 6, 24, 48 h and 3 months from admission for AIS patients). Major adverse clinical events (MACE) (all-cause death, acute myocardial infarction, stroke or hospitalization for heart failure) in STEMI patients and all-cause death in AIS patients were recorded during a 12-month follow-up.

Results

Mean age of the study population was 59 ± 12 and 69 ± 15 years in STEMI and AIS patients, respectively. In STEMI patients, sST2 peaked 24 h after admission (25.5 ng/mL interquartile range (IQR) [14.9–29.1]) whereas an earlier and lower peak was observed in AIS patients (16.8 ng/mL IQR [15.2–18.3] at 6 h). Twenty-five (10.0%) STEMI patients experienced a MACE and 12 (7.9%) AIS patients had all-cause death within the first 12 months. A high level of sST2 at 24 h was associated with MACE in STEMI patients (hazard ratio (HR) = 2.5; 95% confidence interval (CI) [1.1–5.6], p = 0.03) and all-cause death in AIS patients (HR = 11.7; 95% CI [3.8–36.2], p < 0.01) within the first 12 months.

Conclusions

The study highlights that sST2 levels at 24 h are associated with an increased risk to adverse clinical events in both diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ong SB, Hernández-Reséndiz S, Crespo-Avilan GE et al (2018) Inflammation following acute myocardial infarction: multiple players, dynamic roles, and novel therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther 186:73–87

Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA (1999) Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci 22:391–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01401-0

Chamorro Á, Meisel A, Planas AM et al (2012) The immunology of acute stroke. Nat Rev Neurol 8:401–410. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2012.98

Griesenauer B, Paczesny S (2017) The ST2/IL-33 axis in immune cells during inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 8:475. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00475

Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, De Keulenaer GW et al (2002) Expression and regulation of ST2, an interleukin-1 receptor family member, in cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction. Circulation 106:2961–2966. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000038705.69871.D9

Fairlie-Clarke K, Barbour M, Wilson C et al (2018) Expression and function of IL-33/ST2 axis in the central nervous system under normal and diseased conditions. Front Immunol 9:2596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02596

Mirchandani AS, Salmond RJ, Liew FY (2012) Interleukin-33 and the function of innate lymphoid cells. Trends Immunol 33:389–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2012.04.005

Kakkar R, Lee RT (2008) The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 7:827–840

Shimpo M, Morrow DA, Weinberg EO et al (2004) Serum levels of the interleukin-1 receptor family member ST2 predict mortality and clinical outcome in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 109:2186–2190. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000127958.21003.5A

Wolcott Z, Batra A, Bevers MB et al (2017) Soluble ST2 predicts outcome and hemorrhagic transformation after acute stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 4:553–563. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.435

Andersson C, Preis SR, Beiser A et al (2015) Associations of circulating growth differentiation factor-15 and st2 concentrations with subclinical vascular brain injury and incident stroke. Stroke 46:2568–2575. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009026

Tian X, Guo Y, Wang X et al (2020) Serum soluble ST2 is a potential long-term prognostic biomarker for transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol 27:2202–2208. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14419

Mechtouff L, Bochaton T, Paccalet A et al (2020) Association of Interleukin-6 levels and futile reperfusion after mechanical thrombectomy. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011268

Mechtouff L, Bochaton T, Paccalet A et al (2020) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 relationship with infarct growth and hemorrhagic transformation in the era of thrombectomy. Front Neurol 11:473. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00473

Mechtouff L, Bochaton T, Paccalet A et al (2020) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 are associated with collateral status in acute ischemic stroke with large vessel occlusion. Stroke 51:2232–2235. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029395

Bochaton T, Paccalet A, Jeantet P et al (2020) Heat shock protein 70 as a biomarker of clinical outcomes after STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol 75:122–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.044

The TIMI Study Group (1985) The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) trial: phase I findings. N Engl J Med 312:932–936. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198504043121437

Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J, Buchan AM (2000) Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. ASPECTS Study Group. Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score. Lancet 355:1670–1674. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02237-6

Higashida RT, Furlan AJ (2003) Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 34:e109–e137. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000082721.62796.09

Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C et al (1995) Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke: the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA 274:1017–1025. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530130023023

Dieplinger B, Bocksrucker C, Egger M et al (2017) Prognostic value of inflammatory and cardiovascular biomarkers for prediction of 90-day all-cause mortality after acute ischemic stroke-results from the Linz stroke unit study. Clin Chem 63:1101–1109. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.269969

Korhonen P, Kanninen KM, Lehtonen Š et al (2015) Immunomodulation by interleukin-33 is protective in stroke through modulation of inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 49:322–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.013

Chen W, Lin A, Yu Y et al (2018) Serum soluble ST2 as a novel inflammatory marker in acute ischemic stroke. Clin Lab. https://doi.org/10.7754/Clin.Lab.2018.180105

Bochaton T, Lassus J, Paccalet A et al (2021) Association of myocardial hemorrhage and persistent microvascular obstruction with circulating inflammatory biomarkers in STEMI patients. PLoS ONE 16:e0245684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245684

Yang Y, Liu H, Zhang H et al (2017) ST2/IL-33-dependent microglial response limits acute ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci 37:4692–4704. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3233-16.2017

Seki K, Sanada S, Kudinova AY et al (2009) Interleukin-33 prevents apoptosis and improves survival after experimental myocardial infarction through ST2 signaling. Circ Heart Fail 2:684–691. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.873240

Biaggi P, Ammann C, Imperiali M et al (2019) Soluble ST2—a new biomarker in heart failure. Cardiovasc Med. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2019.02008

Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ et al (2007) IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest 117:1538–1549. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI30634

Luo Q, Fan Y, Lin L et al (2018) Interleukin-33 protects ischemic brain injury by regulating specific microglial activities. Neuroscience 385:75–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.05.047

Luo Y, Zhou Y, Xiao W et al (2015) Interleukin-33 ameliorates ischemic brain injury in experimental stroke through promoting Th2 response and suppressing Th17 response. Brain Res 1597:86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.005

Zhang SR, Piepke M, Chu HX et al (2018) IL-33 modulates inflammatory brain injury but exacerbates systemic immunosuppression following ischemic stroke. JCI Insight 3:e121560. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.121560

Xiao W, Guo S, Chen L, Luo Y (2019) The role of Interleukin-33 in the modulation of splenic T-cell immune responses after experimental ischemic stroke. J Neuroimmunol 333:576970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.576970

Xie D, Liu H, Xu F et al (2021) IL33 (Interleukin 33)/ST2 (Interleukin 1 Receptor-Like 1) axis drives protective microglial responses and promotes white matter integrity after stroke. Stroke 52:2150–2161. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032444

Liu X, Hu R, Pei L et al (2020) Regulatory T cell is critical for interleukin-33-mediated neuroprotection against stroke. Exp Neurol 328:113233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113233

Guo S, Luo Y (2020) Brain Foxp3+ regulatory T cells can be expanded by Interleukin-33 in mouse ischemic stroke. Int Immunopharmacol 81:106027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106027

Ito M, Komai K, Mise-Omata S et al (2019) Brain regulatory T cells suppress astrogliosis and potentiate neurological recovery. Nature 565:246–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0824-5

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Clinical Investigation Center for all the work that has been performed in data collection and management for this study. Human biological samples and associated data were obtained from NeuroBioTec (CRB HCL, Lyon France, Biobank BB-0033-00046). We also thank Joe Kelk for proofreading the English and Murielle Robert for her support.

Funding

This work was supported by the RHU MARVELOUS (ANR-16-RHUS-0009) of Université de Lyon, within the program "Investissements d'Avenir" operated by the French National Research Agency (ANR). AP was supported by the «Fondation pour la recherche médicale» (FDT202012010540).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (IRB number: 2015-067B for HIBISCUS-STEMI, IRB number: 00009118 for HIBISCUS-STROKE, CPP Sud-Est III, IRB number: 00009118 for HIBISCUS-STROKE, CPP Sud-Est III) and all subjects or their relatives signed an informed consent form.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mechtouff, L., Paccalet, A., Crola Da Silva, C. et al. Prognosis value of serum soluble ST2 level in acute ischemic stroke and STEMI patients in the era of mechanical reperfusion therapy. J Neurol 269, 2641–2648 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10865-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10865-3