Abstract

Primary schizophreniform psychoses are thought to be caused by complex gene–environment interactions. Secondary forms are based on a clearly identifiable organic cause, in terms of either an etiological or a relevant pathogenetic factor. The secondary or “symptomatic” forms of psychosis have reentered the focus stimulated by the discovery of autoantibody (Ab)-associated autoimmune encephalitides (AEs), such as anti-NMDA-R encephalitis, which can at least initially mimic variants of primary psychosis. These newly described secondary, immune-mediated schizophreniform psychoses typically present with the acute onset of polymorphic psychotic symptoms. Over the course of the disease, other neurological phenomena, such as epileptic seizures, movement disorders, or reduced levels of consciousness, usually arise. Typical clinical signs for AEs are the acute onset of paranoid hallucinatory symptoms, atypical polymorphic presentation, psychotic episodes in the context of previous AE, and additional neurological and medical symptoms such as catatonia, seizure, dyskinesia, and autonomic instability. Predominant psychotic courses of AEs have also been described casuistically. The term autoimmune psychosis (AP) was recently suggested for these patients. Paraclinical alterations that can be observed in patients with AE/AP are inflammatory cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathologies, focal or generalized electroencephalographic slowing or epileptic activity, and/or suspicious “encephalitic” imaging findings. The antibody analyses in these patients include the testing of the most frequently found Abs against cell surface antigens (NMDA-R, CASPR2, LGI1, AMPA-R, GABAB-R), intracellular antigens (Hu, Ri, Yo, CV2/CRMP5, Ma2 [Ta], amphiphysin, GAD65), thyroid antigens (TG, TPO), and antinuclear Abs (ANA). Less frequent antineuronal Abs (e.g., against DPPX, GABAA-R, glycine-R, IgLON5) can be investigated in the second step when first step screening is negative and/or some specific clinical factors prevail. Beyond, tissue-based assays on brain slices of rodents may detect previously unknown antineuronal Abs in some cases. The detection of clinical and/or paraclinical pathologies (e.g., pleocytosis in CSF) in combination with antineuronal Abs and the exclusion of alternative causes may lead to the diagnosis of AE/AP and enable more causal therapeutic immunomodulatory opportunities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are severe and frequent conditions characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disorganization, formal thinking changes, catatonia, and different negative symptoms typically occurring for the first-time during adolescence and early adulthood [65]. Primary schizophreniform psychoses are caused by a complex interaction between multiple genes and environmental factors [81]. Large, genome-wide studies have identified over 100 distinct gene sites that contribute to the relative risk of psychotic symptoms [73]. Secondary forms are based on clearly identifiable causes in the sense of etiology or according to recognizable pathogenesis [45, 81]. Such secondary forms can be linked to autoantibody (Ab)-associated autoimmune processes such as anti-N-Methyl-d-aspartate receptor [NMDA-R] encephalitis [44]. In 2007, the field of autoimmune encephalitis (AE) was redefined with the first description of anti-NMDA-R encephalitis [16, 18, 19]. Since then, a large number of other antineuronal Abs against cell surface antigens and their associated syndromes have been identified [15, 17, 31, 89, 90]. Because these syndromes can be accompanied by polymorphic psychotic symptoms, immunological concepts of schizophreniform psychoses have gained considerable attention since [1, 6, 15, 22, 36, 67, 68, 76, 77, 78, 84]. In a German case series of 100 patients with different forms of AEs with Abs against antineuronal antigens, over half of the patients (60%) presented with psychotic symptoms [36]. In most cases that are positive for antineuronal Abs, patients develop clear neurological symptoms in the course of the disease, such as dystonic movement disorders or epileptic seizures [31, 36, 51]. For AE with predominant psychotic symptoms, the term “autoimmune psychosis” (AP) was recently suggested [21, 61, 67]. The changing nomenclature for autoimmune neuropsychiatric phenomena is summarized in Box 1.

Rationale

The awareness of the fact that psychotic syndromes may have autoimmune, Ab-associated causes opens up a new field in psychiatry for a small but probable relevant subgroup of patients. For clinicians, this raises the question as to how far the diagnostic workup and immunomodulating therapy attempts should be advanced in individual cases. This article investigates this question by illustrating constellations in which extended organic diagnostic procedures, especially Ab analyses, should be carried out.

Clinical symptomatology

The syndrome of possible autoimmune encephalitis

In a current consensus article, experts in the field of neurology and neuroimmunology described the syndrome diagnosis of a possible AE. Accordingly, an autoimmune etiology should be considered if the following criteria are present:

-

1.

Subacute onset (less than 3 months) of deficits in working memory, altered mental state (changes in consciousness, changes in personality, or lethargy) or psychiatric (e.g., psychotic) symptoms.

-

2.

One of the following findings:

-

New focal neurological symptoms.

-

New epileptic seizures.

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) signs of “encephalitis” (temporal FLAIR hyperintensities, multifocal demyelinating or inflammatory lesions).

-

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis (> 5 per mm3).

-

- 3.

Established neuropsychiatric syndromes

From a clinical perspective, different established Ab-associated neuropsychiatric syndromes with generally mixed psychiatric and neurological symptoms can be identified (Table 1). In particular, limbic and anti-NMDA-R encephalitis are established central nervous system (CNS) syndromes that can go along with psychotic syndromes [31]. Various Ab-associated immunological systemic diseases, such as the prototype of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NP-SLE), but also antiphospholipid syndrome, Sjögren’s syndrome, scleroderma, or (ANCA associated) vasculitis may also be associated with psychotic syndromes [63].

-

Limbic encephalitis (LE): LE is characterized by the subacute development of deficits in working memory, paranoid symptoms, hallucinations, irritability, affective symptoms including emotional instability, and epileptic seizures with leading temporal semiology [68]. LE is often associated with specific Abs against cell surface antigens (e.g., LGI-1, GABAB-R, and AMPA-R) or intracellular antigens (e.g., GAD65, Hu, and Ma2 [31, 52]).

-

Anti-NMDA-R encephalitis: This is the most common form of AE, and case series with > 500 patients are published [86]. Tumor association depends on age and gender: in children, tumor association is rare. By contrast, 58% of women from 18 to 45 years suffered from paraneoplastic forms, most commonly with ovarian teratomas [15, 86]. The symptoms usually develop in similar phases including psychotic/catatonic symptoms ([14, 15]; Fig. 1) or in case of relapses [44].

-

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy/steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT): This is a nosologically unclear, probably etiologically heterogeneous syndromatic diagnosis based on the detection of antibodies against specific thyroid antigens (TPO, TG), non-specific paraclinical findings [e.g., blood–brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction in CSF, electroencephalography (EEG) slowing, MRI white matter lesions, after exclusion of antineuronal Abs in serum and CSF (including tissue-based assay)], and steroid responsiveness [22, 48]. Most authors argue that the thyroid Abs have no functional relevance, are rather indicators of an increased autoimmune susceptibility and that, therefore, this diagnosis will decrease with the further discovery of new, specific antineuronal Abs. In line with these observations, a recent study indicates that the current criteria (see Table 1) do not allow a prediction of steroid responsiveness [57]. Better additional clinical, laboratory or instrumental-based diagnostic parameters as predictors of steroid response need to be explored; the criteria of Hashimoto’s encephalopathy must, therefore, be viewed critically [57].

-

Neuropsychiatric SLE (NP-SLE): The clinical picture of NP-SLE is usually a mixed neurological and psychiatric presentation, with systemic signs often providing decisive diagnostic indications. However, rare cases may present primarily with a classical schizophreniform phenotype [54]. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria are well established (Table 1), newer classification criteria such as the Systemic Lupus Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria take laboratory findings more into account (https://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/Criteria/ACR-Endorsed-Criteria; [66]).

Predominant and isolated autoimmune psychosis

In addition to the established main neuropsychiatric syndromes, milder Ab-associated autoimmune disorders with predominant or even isolated schizophreniform psychosis have been described in individual cases [23,24,25, 27,28,29, 44, 54, 56, 83]. For a subgroup of 23 out of 571 (4%) patients with anti-NMDA-R encephalitis, Kayser and colleagues described episodes with purely psychiatric presentations. Five patients developed an initial encephalitis with isolated psychotic symptoms (0.9%), and 18 patients (3.2%) had isolated psychiatric symptoms during a relapse [44]. In the meantime, cases with isolated anti-NMDA-R Ab detection in the serum and typical [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) alterations were published [28]. In a case collection of 46 classic psychiatric Hashimoto encephalopathy cases, 12 patients suffered from acute psychosis (26.1%), and one patient met the criteria for schizophrenia (2.2%) [59]. Abs against intracellular antigens also may be associated with classical schizophreniform syndromes in rare individual cases [24, 60]. Tissue-based assays helped to detect new antineuronal Abs with neuropil pattern and yet unspecified target epitopes [27]. For such psychiatric manifestations of AE, the concept of AP was suggested and consensus criteria for possible, probable, and definite AP have recently been proposed for the first time ([67]; Table 2).

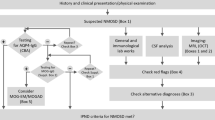

Red flags that should lead to antibody diagnostics

The relatively rapid development of a psychotic syndrome, atypical and often polymorphic clinical symptoms and the presence of other neurological and/or medical symptoms are typical signs in autoimmune pathogenesis and thus should prompt broad Ab analyses [22]. Certain constellations in the course of the disease and typical additional findings should also trigger clinicians to consider the possibility of an AE/AP (Fig. 2; [2, 22, 36, 67, 76, 77, 84, 85]).

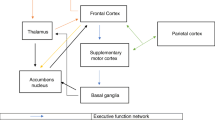

Pathophysiology

Established antineuronal antibodies

Abs against neuronal epitopes can be divided into Abs against cell surface antigens, which are most frequently associated with schizophreniform psychoses, and those against intracellular antigens [15, 36, 67].

-

Abs against cell surface antigens These Abs bind to synaptic receptors, ion channels, or other cell surface proteins. This enables pathogenic Abs to lead to functional changes in electrophysiological signaling or synaptic transmission [8, 47, 68]. Therefore, they can have a direct pathogenic meaning. The exact pathophysiological processes are partly understood. Ab formation can be tumor-triggered. In addition, herpes simplex or other infections can act as triggers of the pathogenic process [4, 42]. Apart from that, Ab production can be the expression of autoimmune predisposition [15]. The initial hope that the anti-NMDA-R Abs at disease onset could provide an explanation for the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia [75, 87] could not be confirmed. Some of the largest Ab studies to date (with > 1000 schizophrenia patients), which were limited to blood serum examinations, have shown similar prevalence rates of different Abs (across all Ab classes, especially IgA and IgM isotypes) in the serum of patients with schizophrenia and controls, predominantly with very low Ab titers [13, 33]. At the same time, Ab detection in CSF appears to be less frequently [26, 64]; in a study of 124 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, even all CSF tests were negative for antibodies against NMDAR, AMPAR, CASPR2, LGI1, and GABAA/BR [64].

-

Abs against intracellular antigens Abs against non-synaptic intracellular antigens (e.g., Hu) typically occur paraneoplastically and have no direct pathogenic effect. They merely represent an epiphenomenon of a systemic tumor-triggered immune process. The cause of the inflammatory brain damage is a misguided response of cytotoxic T cells [51, 79]. There are often early and irreversible structural neuronal damages [79]. Abs against synaptic intracellular antigens are the “stiff-person spectrum” Abs against GAD65 and amphiphysin [51]. Anti-GAD65 Abs are more common idiopathically, and it has not been conclusively determined whether they have a pathogenetic significance or are only an epiphenomenon of another immune process [15].

Systemic “possibly antineuronal” antibodies

These Abs do not bind exclusively to neuronal structures and can also be found together with antineuronal Abs in the context of an autoimmune predisposition [52]. Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) can bind to ubiquitous nuclear structures (e.g., ds-DNA), but also to NMDA receptors and activate them. Therefore, excitotoxicity mediated by an acute NMDA receptor as well as subacute activation of microglia cells can lead to the destruction of synapses [62]. Thyroid Abs also occurs in about 13% of the healthy population [31], and serum Ab titers do not clearly correlate with symptom expression [48]; therefore, most authors have regarded them as an epiphenomenon [22].

Diagnostic approach

Indication for antibody analyses

The indication for serum and CSF Ab analyses results from the above-mentioned red flags (Fig. 2). The following considerations and operationalizations represent a kind of clinical consent among the authors who are all active in clinical diagnosis and management of new onset psychiatric and in particular psychotic patients. In the authors’ opinion, Ab measurements should be performed at least in the following constellation (compare with [36, 61, 67, 76, 77, 82, 85]):

All serum-Ab findings should be interpreted in the context of extended history data, the clinical syndrome, and the examination findings (especially including CSF Ab testing; [51, 82, 85]). The following investigations are suggested for patients with potential immunological genesis [82, 85]:

-

Extended history: Infections/infectious prodroms and tumors should be looked for as possible triggers of Ab production. Attention should also be paid to a predisposition for immunological systemic diseases (presence of rheumatological diseases, inflammatory skin diseases, etc.). In addition, risk factors (such as earlier epileptic seizures, earlier episodes with encephalitides, infections), systemic signs (e.g., CNS or gastrointestinal symptoms), patient’s medication history (e.g., tolerability of antipsychotics), and family history should be inquired into.

-

Medical and neurological physical examination: The medical examination should focus on possible signs for autonomic dysfunction or feverish conditions. In addition, attention should be paid to newly occurring neurological symptoms such as dyskinesia, or myoclonus.

-

Neuropsychological testing: Neuropsychological testing should be considered to objectify more subtle cognitive deficits and to establish an objective follow-up parameter. The corresponding diagnostics can be based on standards of the established German GENERATE network (https://generate-net.de/generate-sops.html), which recommends carrying out bedside screening tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and extended tests such as the Test Battery for Attention Testing, Verbal Learning and Memory Test, Ray Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, or Frontal Assessment Battery, etc.

-

Laboratory measurements: The basic parameters of CSF are very important for differential diagnostic considerations. Pleocytosis or CSF-specific OCBs provide information about a possible inflammatory process in the CNS. Based on the level of pleocytosis, autoimmune and infectious inflammations can often be distinguished [69]. Autoimmune genesis is usually accompanied by mild pleocytosis (from ≥ 5 to 100 per mm3; [31]), and the albumin quotient CSF/serum informs about the blood-CSF-barrier function, which should be assessed using the Reiber scheme [39, 72]. Serological analyses should exclude hyponatremia, which can be associated with anti-LGI1 Abs [88]. Box 2 puts forward a proposal for a two-step Ab diagnostic approach (compare with [82]). The determination of CSF is more sensitive for some Abs against established neuronal surface antigens; up to 14% of patients with anti-NMDA-R encephalitis had anti-NMDA-R Abs only in CSF [32]. The determination of Abs in serum and CSF enables the calculation of Ab indices (normalized to the total IgG ratio CSF/blood and the BBB function; [92]). Infectious (e.g., viral encephalitis), toxic, and other causes should be excluded.

-

EEG: It is a sensitive, although not very specific, tool in the diagnosis of AEs [48, 86]. EEG examinations should, therefore, be carried out on a low-threshold basis [82, 85].

-

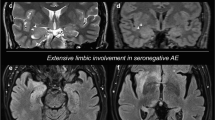

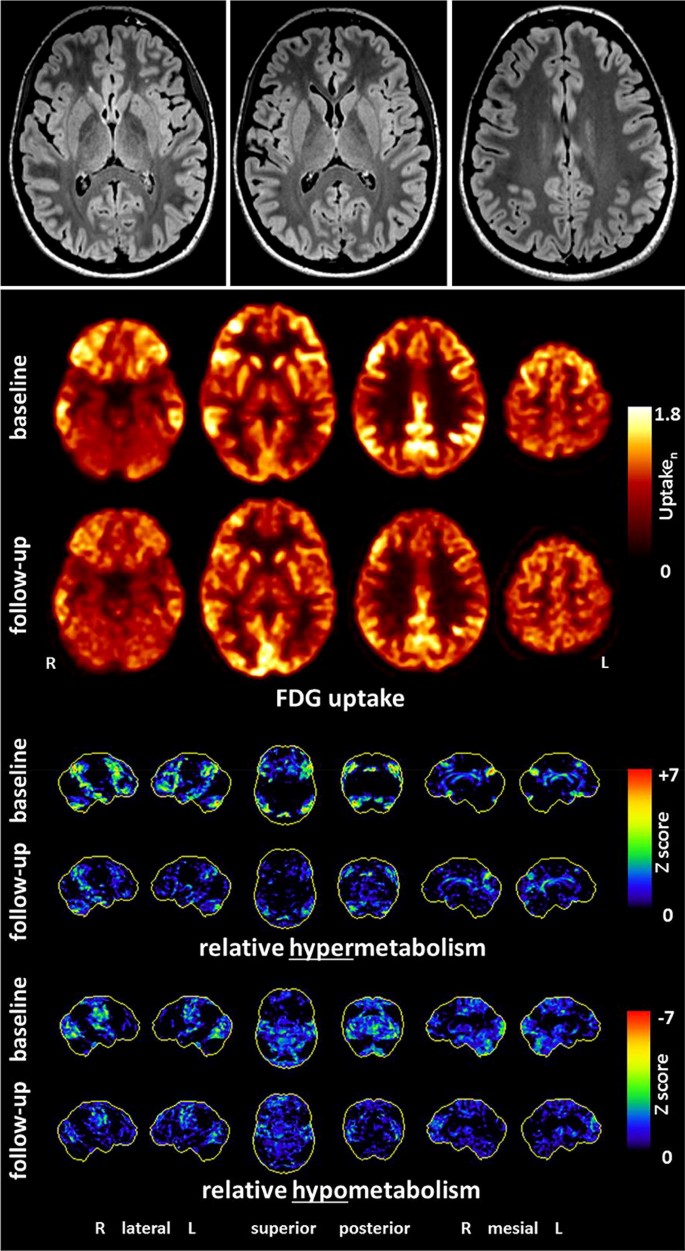

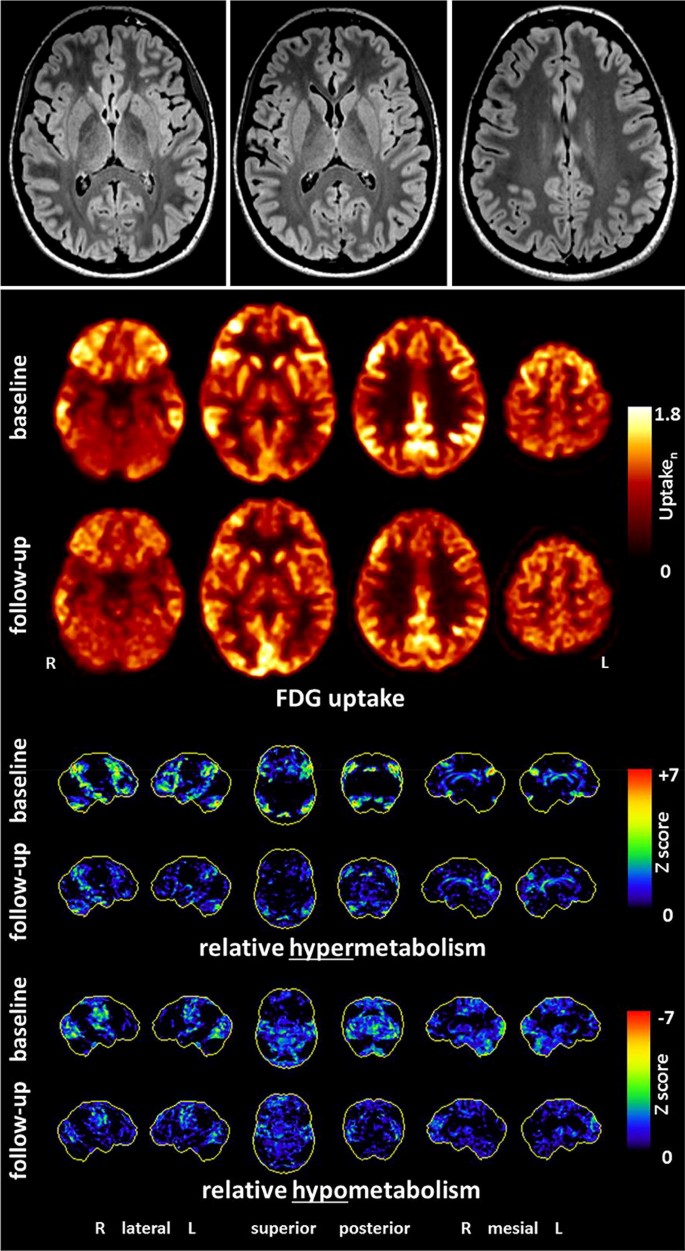

Imaging: In LEs, MRI diagnostics usually show mesiotemporal hyperintensities in the T2 or FLAIR sequences [35]. In AEs with Abs against neuronal cell surface antigens, MRI often remains inconspicuous [35, 86]. The following sequences are suggested by the German GENERATE network: FLAIR axial + FLAIR coronary hippocampal view, T2 coronary, DWI axial and coronary, T2* axial or SWI, T1 + contrast agent axial, T1-MPRAGE (1 × 1 × 1 mm; before contrast agent; https://generate-net.de/generate-sops.html). If the findings remain unclear, an FDG-PET examination can be considered for specific questions. Compared to MRI, FDG-PET possibly has higher sensitivity for inflammatory changes ([5, 28, 35]; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

(©Endres et al., 2019, Front Neurol. Nov 5 [28]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.01086/full)

Findings of a 21-year-old female patient with probable anti-NMDA-R encephalitis. Magnetic resonance imaging depicted only a few slight, nonspecific bifrontal white matter lesions. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed pronounced relative hypermetabolism of her association cortices and a relative hypometabolism of the primary cortices (at baseline), which quickly improved during the follow-up examination after anti-inflammatory treatment

-

Tumor screening Tumor screening is essential in the event of the detection of paraneoplastic, onconeural antineuronal Abs.

Organic differential diagnosis

Primary forms of schizophreniform psychoses must be distinguished not only from secondary Ab-mediated AEs but also from other CNS diseases (Table 4).

Therapeutic experiences and considerations

For the treatment of AE/AP, not only are the classical symptomatic therapy approaches available, but more causal therapy options also exist with immunosuppressive agents and in case of paraneoplastic disease with tumor treatment. Immunosuppressive and tumor therapy should be coordinated in a multidisciplinary setting [76, 77, 82]. Because controlled therapy studies are not yet available, immunosuppressive treatments have so far been carried out in the form of individual therapy trials [79, 90].

Symptomatic treatment

The risk for extrapyramidal motor side effects seems to be increased in patients with AEs [49, 67, 76, 77]. Therefore, psychotic symptoms in the context of AP can be symptomatically treated with antipsychotics with a low risk for motor side effects [76, 77]. Benzodiazepines can be used for anxiolysis and sedation and, in higher doses, for the treatment of catatonic symptoms [76, 77].

Causal immunosuppressive/tumor treatment

The first-line therapy for established AEs is high-dose steroids (e.g., 500–1000 mg methylprednisolone over three to five days; [11, 76, 77, 82, 84]). Possible steroid-induced affective, suicidality, psychotic, and other side effects must be explained in advance [30] and closely monitored. Based on previous experiences, intravenous immunoglobulins or plasmapheresis/immunoadsorption can also be used as a first-line treatment [31, 51, 58, 76, 77, 79]. Rituximab or cyclophosphamide are recommended as “escalation”/“second line” therapies [11, 31, 51, 58, 76, 77, 79]. If relapse prevention turns out to be necessary, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or methotrexate are often used ([51]; Fig. 4). The decision for immunomodulatory maintenance/relapse prevention therapies is often complicated, depending on several factors, and should, therefore, only be made after a multidisciplinary discussion and under regular follow-up investigations. Depending on the Ab type, slightly different approaches have been established, which cannot be discussed in detail here. The aim of tumor treatment in paraneoplastic syndromes is to switch off the ectopic antigen source that maintains the autoimmune process ([79], Table 3).

Therapeutic experiences and considerations for patients with autoimmune encephalitides and established antineuronal antibodies [11, 51, 58, 76, 77, 79, 82]. However, in individual cases, special features must be taken into account, depending on the individual autoantibodies/syndromes/circumstances. *Rituximab is increasingly used as a first-line therapy. **Treatment with cyclophosphamide should be used only with caution in young patients because of the relevant germ cell damage

Limitations

The recommendations worked out here for Abs assessment and respective diagnostic and therapeutic consequences in schizophreniform psychoses were based on consensus from emerging clinical evidence rather than from systematic randomized studies as is the case with the present recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of AE [31]. Beyond, it should be recognized that indeed both well-established clinical terms (like encephalitis, encephalopathy, neuroinflammation) and newly proposed terms (such as AP, AE) are hardly exactly defined, thus for clinical use typically represent just clinical case definitions based on respective limited and steadily emerging clinical consensus [6, 12]. In addition, the possibility of underlying so far not identified new Abs is also limiting the whole issue. Finally, it should be pointed out again that low-positive serum antineuronal Ab titers without signs of brain involvement may occur nonspecifically and do not provide indication for treatment [13, 33, 50, 67].

Conclusion

AE/AP represent a new field for psychiatry. The exact prevalence and thus clinical relevance of classical psychotic manifestations of AEs cannot yet be clearly established. However, the fact that predominant and even isolated psychotic clinical pictures may arise as a result of such AEs in certain cases is casuistically proven for most of the subtypes discussed here and already led to the first immunological treatment trials in Ab seropositive patients with psychosis [50]. Additionally, the topic has been captured in the new German S3 guideline for schizophrenia [20]. Future randomized-controlled and multimodal trials also taking into consideration CSF-results and Ab-titers are needed to shed more light on the relationship between the Abs and the outcome of psychosis discussed here.

References

Al-Diwani A, Handel A, Townsend L, Pollak T, Leite MI, Harrison PJ, Lennox BR, Okai D, Manohar SG, Irani SR (2019) The psychopathology of NMDAR-antibody encephalitis in adults: a systematic review and phenotypic analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Psychiatry 6(3):235–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30001-X(Epub 2019 Feb 11)

Al-Diwani A, Pollak TA, Langford AE et al (2017) Synaptic and neuronal autoantibody-associated psychiatric syndromes: controversies and hypotheses. Front Psychiatry 6(8):13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00013(eCollection 2017)

Ariño H, Armangué T, Petit-Pedrol M et al (2016) Anti-LGI1-associated cognitive impairment: presentation and long-term outcome. Neurology 87(8):759–765. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003009(Epub 2016 Jul 27)

Armangue T, Spatola M, Vlagea A et al (2018) Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: a prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol 17(9):760–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30244-8

Baumgartner A, Rauer S, Mader I et al (2013) Cerebral FDG-PET and MRI findings in autoimmune limbic encephalitis: correlation with autoantibody types. J Neurol 260(11):2744–2753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-013-7048-2(Epub 2013 Jul 31)

Bechter K (2019) Encephalitis, mild encephalitis, neuroprogression, or encephalopathy-not merely a question of terminology. Front Psychiatry 9:782. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00782(eCollection 2018)

Bien CG (2012) Immunvermittelte Erkrankungen der grauen ZNS-Substanz sowie Neurosarkoidose. S1-Leitlinie. Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie

Bien CG, Bauer J (2013) Pathophysiology of antibody-associated diseases of the central nervous system. Nervenarzt 84(4):466–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-012-3606-6

Bizzaro N, Villalta D, Giavarina D, Tozzoli R (2012) Are anti-nucleosome antibodies a better diagnostic marker than anti-dsDNA antibodies for systemic lupus erythematosus? A systematic review and a study of metanalysis. Autoimmun Rev 12(2):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2012.07.002(Epub 2012 Jul 15)

Blinder T, Lewerenz J (2019) Cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients with autoimmune encephalitis—a systematic analysis. Front Neurol 25(10):804. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00804

Borisow N, Prüss H, Paul F (2013) Therapeutic options for autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nervenarzt 84(4):461–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-012-3608-4

Coutinho E, Harrison P, Vincent A (2014) Do neuronal autoantibodies cause psychosis? A neuroimmunological perspective. Biol Psychiatry 75(4):269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.040(Epub 2013 Oct 3)

Dahm L, Ott C, Steiner J et al (2014) Seroprevalence of autoantibodies against brain antigens in health and disease. Ann Neurol 76(1):82–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24189(Epub 2014 Jun 23)

Dalmau J, Armangué T, Planagumà J et al (2019) An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: mechanisms and models. Lancet Neurol 18(11):1045–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30244-3(Epub 2019 Jul 17)

Dalmau J, Geis C, Graus F et al (2017) Autoantibodies to synaptic receptors and neuronal cell surface proteins in autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system. Physiol Rev 97(2):839–887. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00010.2016

Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG et al (2008) Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol 7(12):1091–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70224-2(Epub 2008 Oct 11)

Dalmau J, Graus F (2018) Antibody-mediated encephalitis. N Engl J Med 378(9):840–851. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1708712

Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E et al (2011) Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 10(1):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70253-2

Dalmau J, Tuzun E, Wu HY et al (2007) Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol 61(1):25–36

DGPPN e.V. (ed) (2019) for the Guideline Group: S3 Guideline for Schizophrenia. Abbreviated version (English), 2019, Version 1.0, last updated on 29 December 2019. https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/038-009.html. Acessed 3 Mar 2020

Ellul P, Groc L, Tamouza R, Leboyer M (2017) The clinical challenge of autoimmune psychosis: learning from anti-NMDA receptor autoantibodies. Front Psychiatry 8:54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00054(eCollection 2017)

Endres D, Bechter K, Prüss H et al (2019) Autoantibody-associated schizophreniform psychoses: clinical symptomatology. Nervenarzt. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-019-0700-z

Endres D, Perlov E, Riering AN et al (2017) Steroid-responsive chronic schizophreniform syndrome in the context of mildly increased antithyroid peroxidase antibodies. Front Psychiatry 8:64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00064(eCollection 2017)

Endres D, Perlov E, Stich O et al (2015) Case report: low-titre anti-Yo reactivity in a female patient with psychotic syndrome and frontoparieto-cerebellar atrophy. BMC Psychiatry 12(15):112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0486-x

Endres D, Perlov E, Stich O et al (2015) Hypoglutamatergic state is associated with reduced cerebral glucose metabolism in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: a case report. BMC Psychiatry 1(15):186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0552-4

Endres D, Perlov E, Baumgartner A et al (2015) Immunological findings in psychotic syndromes: a tertiary care hospital’s CSF sample of 180 patients. Front Hum Neurosci 10(9):476. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00476(eCollection 2015)

Endres D, Prüss H, Rauer S et al (2020) Probable autoimmune catatonia with antibodies against cilia on hippocampal granule cells and highly suspicious cerebral FDG-PET findings. Biol Psychiatry (in press)

Endres D, Rauer S, Kern W et al (2019) Psychiatric presentation of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Front Neurol 10:1086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01086

Endres D, Vry M, Dykierek P et al (2017) Plasmapheresis responsive rapid onset dementia with predominantly frontal dysfunction in the context of hashimoto’s encephalopathy. Front Psychiatry 8:212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00212

Gable M, Depry D (2015) Sustained corticosteroidinduced mania and psychosis despite cessation: a case study and brief literature review. Int J Psychiatry Med 50(4):398–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217415612735

Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R et al (2016) A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 15(4):391–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9(Epub 2016 Feb 20)

Gresa-Arribas N, Titulaer M, Torrent A et al (2014) Antibody titres at diagnosis and during follow-up of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 13(2):167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70282-5(Epub 2013 Dec 18)

Hammer C, Stepniak B, Schneider A et al (2014) Neuropsychiatric disease relevance of circulating anti-NMDA receptor autoantibodies depends on blood-brain barrier integrity. Mol Psychiatry 19(10):1143–1149. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.110(Epub 2013 Sep 3)

Hara M, Arino H, Petit-Pedrol M et al (2017) DPPX antibody-associated encephalitis: main syndrome and antibody effects. Neurology 88(14):1340–1348. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003796(Epub 2017 Mar 3)

Heine J, Pruess H, Bartsch T et al (2015) Imaging of autoimmune encephalitis—relevance for clinical practice and hippocampal function. Neuroscience 19(309):68–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.037(Epub 2015 May 23)

Herken J, Prüss H (2017) Red flags: clinical signs for identifying autoimmune encephalitis in psychiatric patients. Front Psychiatry 16(8):25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00025(eCollection 2017)

Honorat J, Komorowski L, Josephs K et al (2017) IgLON5 antibody: neurological accompaniments and outcomes in 20 patients. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 4(5):e385. https://doi.org/10.1212/nxi.0000000000000385(eCollection 2017 Sep)

Hufschmidt A, Lücking C, Rauer S (2013) Neurologie compact: Für Klinik und Praxis, 6th edn. Thieme, Stuttgart

Huss A, Abdelhak A, Halbgebauer S, Mayer B, Senel M, Otto M, Tumani H (2018) Intrathecal immunoglobulin M production: a promising high-risk marker in clinically isolated syndrome patients. Ann Neurol 83(5):1032–1036. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25237(Epub 2018 May 11)

Jarius S, Hoffmann L, Clover L et al (2008) CSF findings in patients with voltage gated potassium channel antibody associated limbic encephalitis. J Neurol Sci 268(1–2):74–77 (Epub 2008 Feb 20)

Jézéquel J, Rogemond V, Pollak T et al (2017) Cell- and single molecule-based methods to detect anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor autoantibodies in patients with first-episode psychosis From the OPTiMiSE Project. Biol Psychiatry 82(10):766–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.015(Epub 2017 Jul 6)

Joubert B, Dalmau J (2019) The role of infections in autoimmune encephalitides. Rev Neurol (Paris) 175(7–8):420–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2019.07.004(Epub 2019 Jul 29)

Kaplan PW, Sutter R (2013) Electroencephalography of autoimmune limbic encephalopathy. J Clin Neurophysiol 30(5):490–504. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNP.0b013e3182a73d47

Kayser M, Titulaer M, Gresa-Arribas N et al (2013) Frequency and characteristics of isolated psychiatric episodes in anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol 70(9):1133–1139

Keshavan MS, Kaneko Y (2013) Secondary psychoses: an update. World Psychiatry 12:4–15

Kovac S, Alferink J, Ahmetspahic D et al (2018) Update on anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Nervenarzt 89(1):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-017-0405-0

Kreye J, Wenke NK, Chayka M et al (2016) Human cerebrospinal fluid monoclonal N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor autoantibodies are sufficient for encephalitis pathogenesis. Brain 139(Pt 10):2641–2652 (Epub 2016 Aug 20)

Laurent C, Capron J, Quillerou B et al (2016) Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT): characteristics, treatment and outcome in 251 cases from the literature. Autoimmun Rev 15(12):1129–1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2016.09.008(Epub 2016 Sep 15)

Lejuste F, Thomas L, Picard G et al (2016) Neuroleptic intolerance in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 3(5):e280. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000280(eCollection 2016 Oct)

Lennox BR, Tomei G, Vincent SA et al (2018) Study of immunotherapy in antibody positive psychosis: feasibility and acceptability (SINAPPS1). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-318124(Epub ahead of print)

Lewerenz J, Jarius S, Wildemann B et al (2016) Autoantibody-associated autoimmune encephalitis and cerebellitis: clinical presentation, diagnostic work-up and treatment. Nervenarzt 87(12):1293–1299

Leypoldt F, Armangue T, Dalmau J (2015) Autoimmune encephalopathies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1338:94–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12553(Epub 2014 Oct 14)

Leypoldt F, Buchert R, Kleiter I et al (2012) Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis: distinct pattern of disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83(7):681–686. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2011-301969(Epub 2012 May 7)

Lüngen EM, Maier V, Venhoff N et al (2019) Systemic lupus erythematosus with isolated psychiatric symptoms and antinuclear antibody detection in the cerebrospinal fluid. Front Psychiatry 10:226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00226(eCollection 2019)

Ma C, Wang C, Zhang Q, Lian Y (2019) Emerging role of prodromal headache in patients with anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. J Pain Res 12:519–526. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S189301

Mack A, Pfeiffer C, Schneider E et al (2017) Schizophrenia or atypical lupus erythematosus with predominant psychiatric manifestations over 25 years: case analysis and review. Front Psychiatry 8:131. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00131(eCollection 2017)

Mattozzi S, Sabater L, Escudero D et al (2019) Hashimoto encephalopathy in the 21st century. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000008785(Epub ahead of print)

McKeon A (2013) Paraneoplastic and other autoimmune disorders of the central nervous system. Neurohospitalist 3(2):53–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874412453339

Menon V, Subramanian K, Thamizh J (2017) Psychiatric presentations heralding hashimoto’s encephalopathy: a systematic review and analysis of cases reported in literature. J Neurosci Rural Pract 8(2):261–267. https://doi.org/10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_440_16

Najjar S, Pearlman D, Zagzag D et al (2012) Glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody syndrome presenting as schizophrenia. Neurologist 18(2):88–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/NRL.0b013e318247b87d

Najjar S, Steiner J, Najjar A et al (2018) A clinical approach to new-onset psychosis associated with immune dysregulation: the concept of autoimmune psychosis. J Neuroinflamm 15(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1067-y

Nestor J, Arinuma Y, Huerta TS, Kowal C, Nasiri E, Kello N, Fujieda Y, Bialas A, Hammond T, Sriram U, Stevens B, Huerta PT, Volpe BT, Diamond B (2018) Lupus antibodies induce behavioural changes mediated by microglia and blocked by ACE inhibitors. J Exp Med. 215(10):2554–2566. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20180776

Oldham M (2017) Autoimmune encephalopathy for psychiatrists: when to suspect autoimmunity and what to do next. Psychosomatics 58(3):228–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2017.02.014(Epub 2017 Mar 2)

Oviedo-Salcedo T, de Witte L, Kümpfel T et al (2018) Absence of cerebrospinal fluid antineuronal antibodies in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Br J Psychiatry 212(5):318–320. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.24(Epub 2018 Mar 28)

Owen M, Sawa A, Mortensen P (2016) Schizophrenia. Lancet 388(10039):86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01121-6

Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS et al (2012) Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 64(8):2677–2686. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34473

Pollak TA, Lennox B, Müller S et al (2020) An international consensus on an approach to the diagnosis and management of psychosis of suspected autoimmune origin: the concept of autoimmune psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry 7(1):93–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30290-1

Prüss H (2013) Neuroimmunology: new developments in limbic encephalitis. Akt Neurol 40:127–136. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1337973

Prüss H (2015) Antibody diagnostics for suspected autoimmune encephalitis. Arthritis Rheuma 35:110–116

Prüss H, Dalmau J, Arolt V et al (2010) Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis An interdisciplinary clinical picture. Nervenarzt 81(4):396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-009-2908-9

Prüss H, Lennox B (2016) Emerging psychiatric syndromes associated with antivoltage-gated potassium channel complex antibodies. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87(11):1242–1247. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2015-313000(Epub 2016 Jul 19)

Reiber H (1994) Flow rate of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—a concept common to normal blood-CSF barrier function and to dysfunction in neurological diseases. J Neurol Sci 122(2):189–203

Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al (2014) Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511(7510):421–427. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13595(Epub 2014 Jul 22)

Schankin CJ, Kästele F, Gerdes LA, Winkler T, Csanadi E, Högen T, Pellkofer H, Paulus W, Kümpfel T, Straube A (2016) New-Onset headache in patients with autoimmune encephalitis is associated with anti-NMDA-receptor antibodies. Headache 56(6):995–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12853

Steiner J, Bogerts B, Sarnyai Z et al (2012) Bridging the gap between the immune and glutamate hypotheses of schizophrenia and major depression: potential role of glial NMDA receptor modulators and impaired blood-brain barrier integrity. World J Biol Psychiatry 13(7):482–492

Steiner J, Prüß H, Köhler S et al (2018) Autoimmune encephalitis with psychotic symptoms: diagnostics, warning signs and practical approach. Nervenarzt 89(5):530–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-018-0499-z

Steiner J, Prüss H, Köhler S, Frodl T et al (2018) Autoimmune encephalitis with psychosis: warning signs, step-by-step diagnostics and treatment. World J Biol Psychiatry 4:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2018.1555376(Epub ahead of print)

Steiner J, Walter M, Glanz W et al (2013) Increased prevalence of diverse N-methyl-d-aspartate glutamate receptor antibodies in patients with an initial diagnosis of schizophrenia: specific relevance of IgG NR1a antibodies for distinction from N-methyl-d-aspartate glutamate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Psychiatry 70(3):271–278

Stich O, Rauer S (2014) Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and autoimmune encephalitis. Nervenarzt 85(4):485–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-014-4030-x(quiz 499–501)

Tan Z, Zhou Y, Li X et al (2018) Brain magnetic resonance imaging, cerebrospinal fluid, and autoantibody profile in 118 patients with neuropsychiatric lupus. Clin Rheumatol 37(1):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3891-3(Epub 2017 Nov 4)

Tebartz van Elst L (2017) Vom Anfang und Ende der Schizophrenie: Eine neuropsychiatrische Perspektive auf das Schizophrenie-Konzept. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart

Tebartz van Elst L, Bechter K, Prüss H, Hasan A et al (2019) Autoantibody-associated schizophreniform psychoses: pathophysiology, diagnostics, and treatment. Nervenarzt 90(7):745–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-019-0735-1(German)

Tebartz van Elst L, Klöppel S, Rauer S (2011) Voltage-gated potassium channel/LGI1 antibody-associated encephalopathy may cause brief psychotic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 72(5):722–723. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.10l06510

Tebartz van Elst L, Stich O, Endres D (2015) Depressionen und Psychosen bei immunologischen Enzephalopathien. PSYCH up2date 9(05):265–280

Tebartz van Elst L, Süß P, Endres D (2019) Autoimmunenzephalitiden in der psychiatrie—klinische differenzialdiagnostik schizophreniformer psychosen. CME-Fortbildung. InFo Neurol Psychiatr 21(2):39–50

Titulaer MJ, Mccracken L, Gabilondo I et al (2013) Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 12(2):157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70310-1(Epub 2013 Jan 3)

Tebartz van Elst L, Valerius G, Büchert M et al (2005) Increased prefrontal and hippocampal glutamate concentration in schizophrenia: evidence from a magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Biol Psychiatry 58(9):724–730 (Epub 2005 Jul 14)

Vincent A, Buckley C, Schott JM et al (2004) Potassium channel antibody-associated encephalopathy: a potentially immunotherapy-responsive form of limbic encephalitis. Brain 127(Pt 3):701–712 (Epub 2004 Feb 11)

Vincent A, Bien CG, Irani SR et al (2011) Autoantibodies associated with diseases of the CNS: new developments and future challenges. Lancet Neurol 10(8):759–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70096-5

Wandinger KP, Leypoldt F, Junker R (2018) Autoantibody-mediated encephalitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 115(40):666–673. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2018.0666

Weiner SM, Otte A, Uhl M, Brink et al (2003) Neuropsychiatrische Beteiligung des systemischen Lupus erythematodes. Teil 2: diagnostik und Therapie. Med Klin 98(2):79–90

Wildemann B, Oschmann P, Reiber HO (2010) Laboratory diagnosis in neurology, 1st edn. Thieme, Stuttgart

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. DE was supported by the Berta-Ottenstein-Program for Advanced Clinician Scientists, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

DE: None. FL: Consulting/speech fees from Biogen, Grifols, Teva, Roche, Merck, Fresenius. KB: None. AH: Fees for consulting and lectures by Lundbeck, Otsuka, Janssen-Cilag, Roche and Pfizer. He is editor of the WFSBP Schizophrenia Guidelines and coordinator and member of the control group of the S3 Schizophrenia Guidelines. JS: Fees for consulting and lectures within the last 3 years from Janssen-Cilag. KD: Steering Committee Neurosciences, Janssen. KPW: He worked for Euroimmun up to December 2012. He has received payment for a lecture from the laboratory Dr. Fenner and colleagues. PF: Consulting for the past 3 years: Abbott, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Recordati, Richter, Servier, Takeda. VA: He has been working as an advisor and gave lectures for the following pharmaceutical companies: Allergan, Astra-Zeneca, Janssen, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Organon, Sanofi, Servier, and Tromsdorff. OS: None. SR: Receiving consulting and lecture fees, grant and research support from Bayer Vital, Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme, Roche and Teva. Furthermore, SR indicates that he is a founding executive board member of ravo Diagnostika GmbH Freiburg. HP: None. LTvE: Advisory boards, lectures, or travel grants within the last three years: Roche, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Shire, UCB, GSK, Servier, Janssen and Cyberonics. Book publications on schizophrenic disorders, autism and “epilepsy and mind”.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter Falkai.

The authors of this paper have already published several reviews on the topic ([11, 22, 51, 52, 68, 69, 70, 76, 77, 79, 82, 84, 85]). There may, therefore, be overlaps in wording compared to the other publications. In particular, the current paper is inspired by some articles that have recently been published in German [22, 82, 85].

Dominique Endres, Frank Leypoldt, Harald Prüss and Ludger Tebartz van Elst shared first/last.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Endres, D., Leypoldt, F., Bechter, K. et al. Autoimmune encephalitis as a differential diagnosis of schizophreniform psychosis: clinical symptomatology, pathophysiology, diagnostic approach, and therapeutic considerations. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 270, 803–818 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01113-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01113-2