Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the ongoing DETECT study program is to evaluate therapeutic intervention based on phenotypes of circulating tumor cells (CTC) in patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Currently (as of July 2015) more than half of the projected about 2000 patients with MBC have already been screened for CTC.

Methods

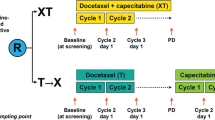

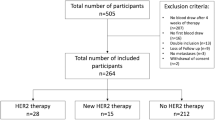

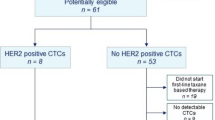

Women with HER2-negative primary tumor and presence of CTC are recruited into different DETECT trials according to the HER2-phenotype of CTC. Patients with HER2-positive CTC are randomized to treatment with physicians’ choice therapy (standard chemo- or endocrine therapy) with or without additional HER2-targeted therapy with lapatinib in the DETECT III trial. In DETECT IVa, postmenopausal patients with hormone-receptor positive primary cancer and HER2-negative CTC receive everolimus and standard endocrine therapy. For women with HER2-negative CTC and triple negative MBC or hormone-receptor positive tumor and indication for chemotherapy, a treatment with eribulin is offered (DETECT IVb). The clinical efficacy is investigated by CTC-Clearance and progression-free survival (PFS). The DETECT V/CHEVENDO trial extends the DETECT study program for women with HER2-positive and hormone-receptor positive MBC. The primary objective of this trial is to compare safety and quality of life (QoL) as assessed by the occurrence of adverse events in patients treated with dual (trastuzumab plus pertuzumab) HER2-targeted therapy plus either endocrine or chemotherapy. The translational research projects of the DETECT study program focus on further molecular characterization of CTC and evaluation of markers for their suitability to predict treatment response and to facilitate the development of more personalized treatment options.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fehm T, Müller V, Aktas B et al (2010) HER2 status of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a prospective, multicenter trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 124:403–412. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1163-x

Bidard F-C, Peeters DJ, Fehm T et al (2014) Clinical validity of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 15:406–414. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70069-5

Budd GT, Cristofanilli M, Ellis MJ et al (2006) Circulating tumor cells versus imaging–predicting overall survival in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 12:6403–6409. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1769

Cristofanilli M, Hayes DF, Budd GT et al (2005) Circulating tumor cells: a novel prognostic factor for newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:1420–1430. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.08.140

Hayes DF, Cristofanilli M, Budd GT et al (2006) Circulating tumor cells at each follow-up time point during therapy of metastatic breast cancer patients predict progression-free and overall survival. Clin Cancer Res 12:4218–4224. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2821

Dawood S, Broglio K, Valero V et al (2008) Circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: from prognostic stratification to modification of the staging system? Cancer 113:2422–2430. doi:10.1002/cncr.23852

Giordano A, Cristofanilli M (2012) CTCs in metastatic breast cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res 195:193–201. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-28160-0_18

Giuliano M, Giordano A, Jackson S et al (2011) Circulating tumor cells as prognostic and predictive markers in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving first-line systemic treatment. Breast Cancer Res 13:R67. doi:10.1186/bcr2907

Wallwiener M, Hartkopf AD, Baccelli I et al (2013) The prognostic impact of circulating tumor cells in subtypes of metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137:503–510. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2382-0

Rack B, Schindlbeck C, Jückstock J et al (2014) Circulating tumor cells predict survival in early average-to-high risk breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju066

Zhang L, Riethdorf S, Wu G et al (2012) Meta-analysis of the prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 18:5701–5710. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1587

Liu MC, Shields PG, Warren RD et al (2009) Circulating tumor cells: a useful predictor of treatment efficacy in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 27:5153–5159. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6664

Pierga J-Y, Hajage D, Bachelot T et al (2012) High independent prognostic and predictive value of circulating tumor cells compared with serum tumor markers in a large prospective trial in first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 23:618–624. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr263

Smerage JB, Barlow WE, Hortobagyi GN et al (2014) Circulating tumor cells and response to chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: SWOG S0500. J Clin Oncol 32:3483–3489. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2561

Santinelli A, Pisa E, Stramazzotti D, Fabris G (2008) HER-2 status discrepancy between primary breast cancer and metastatic sites. Impact on target therapy. Int J Cancer 122:999–1004. doi:10.1002/ijc.23051

Simmons C, Miller N, Geddie W et al (2009) Does confirmatory tumor biopsy alter the management of breast cancer patients with distant metastases? Ann Oncol 20:1499–1504. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp028

Ligthart ST, Bidard F-C, Decraene C et al (2013) Unbiased quantitative assessment of Her-2 expression of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic and non-metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 24:1231–1238. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds625

Hanf V, Schütz F, Liedtke C, Thill M (2014) AGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer: update 2014. Breast Care (Basel) 9:202–209. doi:10.1159/000363551

Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Simes RJ et al (1989) Costs and benefits of adjuvant therapy in breast cancer: a quality-adjusted survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 7:36–44

Glasziou PP, Cole BF, Gelber RD et al (1998) Quality adjusted survival analysis with repeated quality of life measures. Stat Med 17:1215–1229

Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A, Cole BF (1993) Evaluation of effectiveness: Q-TWiST. The International Breast Cancer Study Group. Cancer Treat Rev 19(Suppl A):73–84

Corey-Lisle PK, Peck R, Mukhopadhyay P et al (2012) Q-TWiST analysis of ixabepilone in combination with capecitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer 118:461–468. doi:10.1002/cncr.26213

Sherrill B, Sherif B, Amonkar MM et al (2011) Quality-adjusted survival analysis of first-line treatment of hormone-receptor-positive HER2+ metastatic breast cancer with letrozole alone or in combination with lapatinib. Curr Med Res Opin 27:2245–2252. doi:10.1185/03007995.2011.621209

Dupont Jensen J, Laenkholm A-V, Knoop A et al (2011) PIK3CA mutations may be discordant between primary and corresponding metastatic disease in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 17:667–677. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1133

Kataoka Y, Mukohara T, Shimada H et al (2010) Association between gain-of-function mutations in PIK3CA and resistance to HER2-targeted agents in HER2-amplified breast cancer cell lines. Ann Oncol 21:255–262. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp304

Eichhorn PJA, Gili M, Scaltriti M et al (2008) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase hyperactivation results in lapatinib resistance that is reversed by the mTOR/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor NVP-BEZ235. Cancer Res 68:9221–9230. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1740

Berns K, Horlings HM, Hennessy BT et al (2007) A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 12:395–402. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.030

Hurst CD, Zuiverloon TCM, Hafner C et al (2009) A SNaPshot assay for the rapid and simple detection of four common hotspot codon mutations in the PIK3CA gene. BMC Res Notes 2:66. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-2-66

Bhatia P, Sanders MM, Hansen MF (2005) Expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB is inversely correlated with metastatic phenotype in breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 11:162–165

Trinkaus M, Ooi WS, Amir E et al (2009) Examination of the mechanisms of osteolysis in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Oncol Rep 21:1153–1159

Müller V, Riethdorf S, Rack B et al (2011) Prospective evaluation of serum tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 and carbonic anhydrase IX in correlation to circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 13:R71. doi:10.1186/bcr2916

Giordano C, Cui Y, Barone I et al (2010) Growth factor-induced resistance to tamoxifen is associated with a mutation of estrogen receptor alpha and its phosphorylation at serine 305. Breast Cancer Res Treat 119:71–85. doi:10.1007/s10549-009-0334-0

Herynk MH, Parra I, Cui Y et al (2007) Association between the estrogen receptor alpha A908G mutation and outcomes in invasive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13:3235–3243. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2608

Sutton LM, Cao D, Sarode V et al (2012) Decreased androgen receptor expression is associated with distant metastases in patients with androgen receptor-expressing triple-negative breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 138:511–516. doi:10.1309/AJCP8AVF8FDPTZLH

Thike AA, Yong-Zheng Chong L, Cheok PY et al (2014) Loss of androgen receptor expression predicts early recurrence in triple-negative and basal-like breast cancer. Mod Pathol 27:352–360. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.145

Aktas B, Tewes M, Fehm T et al (2009) Stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers are frequently overexpressed in circulating tumor cells of metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 11:R46. doi:10.1186/bcr2333

Kasimir-Bauer S, Hoffmann O, Wallwiener D et al (2012) Expression of stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in primary breast cancer patients with circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res 14:R15. doi:10.1186/bcr3099

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients for participating at this study and donating their blood samples for research purposes. We also thank Anke Faul and especially Evelyn Jäckel for their excellent support. The DETECT study program is supported by the Investigator-Initiated Study Program of Janssen Diagnostics. The clinical trials are also supported by GlaxoSmithKline GmbH & Co. KG, Pierre Fabre Pharma GmbH, TEVA GmbH, AMGEN GmbH, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Eisai GmbH and Roche Pharma AG. The study medication is provided free of charge by GlaxoSmithKline GmbH & Co. KG (Lapatinib), Pierre Fabre Pharma GmbH (Navelbine oral), TEVA GmbH (non-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin NPLD), Novartis Pharma GmbH (Everolimus), Eisai GmbH (Eribulin) and Roche (Pertuzumab).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Prof. T. Fehm and her project are funded by Novartis Research grant. Prof. Janni receives Research Grant and Honoraria from Janssen Diagnostic as well as support for the DETECT study concept by the listed companies below. PD Dr. Brigitte Rack is supported by Janssen Diagnostics. The other authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schramm, A., Friedl, T.W.P., Schochter, F. et al. Therapeutic intervention based on circulating tumor cell phenotype in metastatic breast cancer: concept of the DETECT study program. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293, 271–281 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3879-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3879-7