Abstract

Background

Due to the complexity of distal humerusfractures and often poor bone quality in elderly patients, these entities remain a challenge. However, because of a high rate of complications related to total elbow prostheses, reconstruction of distal humerus fractures should still be considered a therapeutic option, also in the elderly patient. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the clinical outcomes after open reduction and internal fixation and to evaluate whether the results justify reconstruction even in elderly patients. We hypothesized that despite advanced age, reasonable clinical results can be achieved, using a standardized surgical technique and aftertreatment protocol for the treatment of distal humerus fractures in elderly patients.

Methods

Between 2004 and 2012, 30 patients with a mean age of 78 years at the time of injury with a recent distal humerus fracture were evaluated. All patients underwent the identical aftertreatment protocol with no weight bearing for 6 weeks and weekly increasing range of motion. Follow-up rate was 90%. 22 patients were treated with double plate, 4 with single plate, and 1 with screw fixation only. Patients were evaluated based on clinical criteria. Primary outcome measures were Mayo Elbow Performance Score, VAS and joint range of motion, secondary was radiological evaluation.

Results

After a mean follow-up period of 3.8 years (min. 1 year, max. 9 years, SD ± 2), the average range of motion was flexion of 127° (min. 100°; max. 150°; SD ± 16.5) and average loss of extension of 20.9° (min. 5°; max. 40°; SD ± 11). Average pronation and supination was 68.3° (min. 0°; max. 90°; SD ± 25.3) and 75.3° (min. 0°; max. 90°; SD ± 19.7), respectively. Average Mayo Elbow Performance (MEPS) score was 88.7 (min. 60; max. 100; SD ± 12.1). 6 patients developed heterotopic ossification without significant effect on the clinical outcome. 7 patients had radiological evidence of at least partial non-union with one requiring revision, 2 discrete hardware dislocations were treated conservatively. There were no infections in the presented cohort. Our results regarding the surgical approach showed significantly higher patient satisfaction scores in the osteotomy group, compared to the group with Triceps-On Approach (PTOA).

Conclusion

The present data support indication for open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) even in the elderly patient. Advanced age should not be seen as a contraindication for ORIF of fractures of the distal humerus. Although the rate of complications is higher than in younger patients, complications such as non-union are often asymptomatic, patient satisfaction scores are high, and the possible devastating complications of failed elbow replacement can be evaded.

Level of evidence

IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Distal humeral fractures in the elderly population are on the rise and only little literature exists regarding the fixation. With an increasingly aging population in most countries in the western world, it is of value to know the likely outcome of fracture fixation of the distal humerus in this age group. Court-Brown and Caesar reported on the development of fracture patterns in a stable population of around 500,000 people around Edinburgh [1]. They reported an incidence of distal humeral fractures of 5.8 per 100,000 and noted that this was only 0.5% of all fractures seen. Interestingly, the distribution of distal humerus fractures showed a ‘unimodal older woman’ pattern and falls in what they describe as an osteoporotic curve pattern. This type of curve pattern was not seen in the previous study of Buhr and Cooke from 1959 suggesting that these fractures are on the rise [2]. The largest epidemiological study in the world comes from the Finnish National Hospital Discharge Register; this study looked at all distal humeral fractures in women over the age of 60 for the years 1970–1995. The most significant increase was seen in the oldest women, with an age specific increase of 8 in 1970 and 54 in 1995, representing a sevenfold increase [3]. For all women over 60 years the incidence of distal humerus fractures will triple over the next 20 years [4]. Only a few studies concerning the fixation of these fractures in patients over the age of 70 years were published in the last decade. Studies with large numbers and sufficient follow-up are understandably difficult to achieve in this study population, so any further information is valuable. While these fractures are uncommon, representing only 1–2% of fractures occurring in adults, they are difficult to treat, with options ranging from non-operative management to total elbow replacement [5, 6]. According to the recent literature, total elbow replacement (TEA) comes with a high rate of complications like loosening, deep infection, ulnar nerve lesions. Depending on linked and unlinked systems, the complication rate has been reported to be at 19 and 26% [7, 8]. Assuming an increase of this type of injury and the workload that it will represent in the future, we looked at the functional and radiological outcomes and complications of all our patients aged 70 years and older treated with ORIF for distal humerus fractures over a period of 8 years, to evaluate whether ORIF can achieve adequate results even in elderly patients.

Patients and methods

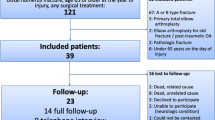

All patients with distal humeral fractures operatively treated with ORIF over an 8-year period between 2004 and 2012 at an urban level 1 trauma centre were retrospectively reviewed. Written informed consent of the patients and approval by the local ethics committee were achieved. The cohort consisted of 30 patients, (27 women and 3 men). Mean age at time of injury was 78 years (range 70–90, SD ± 5.3). 3 patients were lost to follow-up due to natural death, resulting in a 90% follow-up rate for our collective (27 patients). Of these injuries, 6 were Type A, 5 Type B and 16 Type C as per AO Classification (Table 1). Five patients had suffered open fractures (3 Type I and 2 Type II) according to Gustilo–Anderson classification [9, 10]. Average follow-up time was 3.84 years (range 1.1–8.8, SD ± 2), with a minimum of 1 year. 22 patients were treated with double plate osteosynthesis, 4 with a single plate and 1 with screw fixation only. All patients received a plaster of Paris cast post operatively for an average of 2.2 weeks (range 2–6) until removal of skin sutures. The surgical approach involved a posterior midline incision with olecranon osteotomy (n = 11) of chevron type, a posterior triceps-on approach (PTOA) according to Alonso-Llamas, where the distal humerus is approached medially and laterally avoiding detachment of the triceps and avoiding osteotomy of the olecranon (n = 14), muscle splitting (n = 1) or lateral approach only (n = 1) (Table 2) [11]. The osteotomized olecrani were all fixed with a tension band wire technique. In 19 out of 27 patients who showed initially post-traumatic neuropathy of the ulnar nerve or in those, where the nerve was irritated by the positioned osteosynthetic implants, anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve was performed at the time of surgery. Aftertreatment protocol was set identical in all patients with no weight bearing for 6 weeks and then gradual increase of loads after 6-week X-ray control. The range of motion was limited to extension/flexion of 0°/30°/90° for the first week, with then increasing range of motion under physiotherapy over the following weeks. Due to the age of the cohort, not all patients were able to strictly adhere to the protocol. At the final follow-up patients were evaluated clinically and radiologically by an independent observer and X-ray imaging in two orthogonal planes (a.p. and lateral view). Follow-up was at 2, 6, 12 weeks, 6 months and minimum 1 year. Outcome criteria were range of motion, pain [visual analogue scale (VAS)] with 0 meaning no pain and 10 maximum pain), satisfaction score (VAS with 0 meaning unsatisfied and 10 very satisfied) and Mayo elbow performance score (MEPS) with a score of 100 being optimal result. Primary outcome measures were Mayo Elbow Performance Score, VAS and joint range of motion, secondary was radiological evaluation (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis between the osteotomy group and the PTOA group was done with STATISTICA 6.0 (StatSoft, Inc. STATISTICA (data analysis software system). The clinical results in both groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. A p value less than 5% was considered statistically significant. Effect size (R) was calculated as the quotient of the z value and the square root of the sample size.

Results

Mean follow-up period of 3.8 years (min. 1 year, max. 9 years, SD ± 2) the average range of motion was flexion of 127° (min. 100°; max. 150°; SD ± 16.5) and average loss of extension of 20.9° (min. 5°; max. 40°; SD ± 11). Average pronation and supination was 68.3° (min. 0°; max. 90°; SD ± 25.3) and 75.3° (min. 0°; max. 90°; SD ± 19.7), respectively (Fig. 2).

Average pain score was 1.3 out of 10 (range 0–7, SD ± 1.7) and patient satisfaction score was 8.8 (range 5–10, SD ± 1.4). MEPS averaged 88.7 (range 60–100, SD ± 12.1). The MEPS was excellent (90–100) in 17 patients (63%), good (75–89) in 6 patients (22%), fair (61–74) in 3 patients (11%) and poor (60 or less) in 1 patient (4%) (Table 3). The average MEPS for the unaffected elbow was 89 (range 90–100) by comparison. Six patients developed heterotopic ossification (22%), 5 of these 6 were in patients who had undergone olecranon osteotomy. There was no significant difference in the range of motion outcome between the group with heterotopic ossification (mean range − 20° extension to 123 degrees flexion) and without (mean range − 22° extension to 128 degrees flexion). Six patients mal-united, 4 of which in a valgus position (average 8 degrees) and 2 in a varus position (average 10°). Six patients (22%) had clinical and radiological evidence of non-union: three occurred in the olecranon osteotomy group and three in the PTOA group. One required revision plating at 4 months. Hardware complications were observed in two patients, one of whom underwent revision of olecranon fixation; the other one had a plate loosening which was treated conservatively. Two patients, both of whom had undergone ulnar nerve transposition, experienced transient ulnar nerve palsy; one had sustained neurapraxia at time of injury, the other one at time of surgery. Both resolved over time. There were no post-operative infections in the present cohort. Comparing patients with olecranon osteotomy and the ones with PTOA, we found no significant difference between range of motion, pain score and MEPS whereas for satisfaction score, the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05) in favour of olecranon osteotomy (Table 4), despite the higher rate of complex intra-articular fractures treated with this approach. Effect size was found to be r = 0.6325, with r values above 0.5 being seen as strong effect.

Discussion

Based on the present data, ORIF of distal humerus fractures still is a reliable treatment option for fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly. Our series found mostly excellent outcome scores with a low revision rate for patients over 70 years of age.

Several strategies exist for dealing with distal humerus fractures in the elderly, and decision-making depends on fracture configuration, but also patient characteristics. While simple fractures may be sufficiently fixed with only screws [12, 13], more complex patterns of type A fractures as well as type B and C fractures demand plate fixation or even prosthetic replacement. Clavert et al. concluded that for AO type A and B fractures, osteosynthetic fixation provided the best results if the patients had little medical history, no neuropsychiatric disorders and if the fracture occurred on the dominant side [14]. The main predictor of failure was osteoporosis, which increased the risk of clinical and radiological failure fourfold regardless of the type of construct or hardware used [14]. Relevant comorbidities that have significant impact on life expectancy will favour conservative treatment modalities, as shown by the overview of Lander and colleagues [15]. The authors found reasonable results by immobilisation of complex distal humerus fractures in elderly low-demand patients. But Lander’s paper also showed a reduction in mortality, if operative treatment was chosen. In their recent paper, Goyal et al. investigated the risk for re-operation of elderly patients after total elbow arthroplasty or osteosynthesis. Summarizing the results, patients after total elbow arthroplasty had a lower risk of re-operation and a higher death rate at the time of the follow-up, compared to patients after osteosynthesis. Interestingly, the authors found no difference in re-operation when looking at the time interval when angle-stable implants had been used for osteosynthesis. The data might implicate that with modern techniques, reconstruction is reliably possible even in elderly patients. The study of Goyal et al. shows that despite several other studies may have indicated that in elderly patients, arthroplasty should be preferred over osteosynthesis for distal humerus fractures [16,17,18,19], the topic is not closed for discussion. There is still a need for data on the outcomes of distal humerus reconstruction in elderly patients, to feed the discussion.

Although the information that reconstruction of distal humerus fractures is not new [20,21,22], the cohort of this study is of a reasonable size and the data in our eyes add to the body of literature. The present paper reports the experiences of the authors but does not offer precise decision-making guidance for the treatment of distal humerus fractures in elderly patients. It is nearly impossible to find clearly defined cut-off values for when to reconstruct or when to replace the distal humerus. But it documents reliable results for reconstruction. The advantage of reconstruction is retaining the native bone and articular structures. Retaining the bone prevents loosening or implant failure, as it is seen in patients with prosthetic replacement [23]. The few existing reports of internal fixation in general yield good results [24,25,26,27,28]. The guiding principle for the treatment of these fractures remains anatomical reduction at the level of articular cartilage and stable fixation at the level of the columns [29, 30]. The majority of the patients of the present study were treated with ORIF with double plates in an orthogonal pattern. Recent discussions focused on the configuration of double plates at the distal humerus, as a strict medio-lateral plate configuration in a 180° fashion yielded higher primary stability in in vitro study setups, compared to orthogonal plating in 90° [31, 32]. Yet, when looking at the impact of plate position on the clinical outcome, no significant differences could be found [33,34,35,36]. In a prospective randomised study Shin et.al observed no significant difference between the parallel plating method and the orthogonal plating with regard to non-union rates, range of motion and MEPS [36]. Good to excellent MEPSs were observed in 85% of our patients which confirms this statement. Our range of motion outcomes closely matches those seen in similar studies with an average population age of 72 years [37, 38]. The literature is not able to favour either total elbow arthroplasty or internal fixation [39]. Both are surgically challenging in this patient group. Achieving sufficient patient numbers for prospective randomized trials in this age group will almost certainly require multi-centre collaboration.

To the best of our knowledge, our series represents the largest patient cohort treated with ORIF in this age group as published in the literature. Pain scores were low and the complication rates were comparable to those seen in studies with a younger patient base. Our patients were not formally assessed in terms of their bone mineral density, but it is reasonable to assume that in a predominantly female population of 75, osteoporosis will likely be prevalent and indeed epidemiological studies suggest that distal humeral fractures in this age group should now be considered osteoporotic fractures [1]. When PTOA is used, the surgeon has the option to convert to joint replacement, if reconstruction is not feasible. In addition, revision of patients who underwent PTOA is easier to handle with TEA in comparison to those with OO. Thus, in our eyes, OO should be done only after the surgeon sees a realistic chance of stable fixation, especially in the elderly patients.

Our rate of heterotopic ossification at 22% is similar to that reported in other series [25, 40]. It is of note that the presence of heterotopic ossifications did not influence the functional outcome. Transposing the ulnar nerve made no difference to outcome and was predominantly used in cases where nerve mobilization facilitated the fixation. We do not transpose the nerve routinely.

Finally, several limitations of our study have to be mentioned. First, the retrospective study design has to be mentioned. However, a follow-up rate of 90% is more than acceptable for this group of patients and all clinical and radiological evaluations were completed. No comparison group is available, and all surgeries were performed at one single center. The overall number of patients seems to be moderate; but considering the low fracture incidence, this number seems to be acceptable for a single center when compared to other studies.

Successful ORIF in our eyes has potential advantages over joint replacement in the long term although the present study is not fit to prove advantages. ORIF should have place in contemporary treatment plans for distal humerus fractures of elderly patients. Nevertheless, the very distal fractures, or low fractures are difficult to be fixed and replacement should be chosen. This is even more the case when obvious signs of highly reduced bone quality are present. In those with a massive osteoporosis and comminuted low fractures, we consider total elbow arthroplasty as a reliable treatment modality. Hence, we believe that it is worth giving patients regardless of their age a chance to restore the anatomy if possible, and not to promote cut-off values in age for example, beyond which no reconstruction is undertaken anymore. In that regard, we should take into consideration the increasing level of demand in the aging population and should evaluate the “biological age” of the patient and not the absolute numbers.

Conclusions

Outcomes of fractures were good or excellent in 85% of our patients according to their Mayo Elbow Performance Score. Pain scores were also low. A good functional result does of course not reflect the patients overall state of health. However, any treatment that can preserve independence in the elderly has to be valued. Advanced age should not be a contraindication to open reduction and fixation in distal humerus fractures.

References

Court-Brown CM, Caesar B (2006) Epidemiology of adult fractures: a review. Injury 37(8):691–697

Buhr AJCA (1959) Fracture patterns. Lancet 1(7072):531–536

Palvanen M, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Kannus P (2003) Osteoporotic fractures of the distal humerus in elderly women. Ann Intern Med 139(3):W61

Palvanen M, Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J (1998) Secular trends in the osteoporotic fractures of the distal humerus in elderly women. Eur J Epidemiol 14(2):159–164

Helfet DL, Schmeling GJ (1993) Bicondylarintraarticular fractures of the distal humerus in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res 292:26–36

Robinson CM, Hill RM, Jacobs N, Dall G, Court-Brown CM (2003) Adult distal humeral metaphyseal fractures: epidemiology and results of treatment. J Orthop Trauma 17(1):38–47

Prkic A, Welsink C, The B, van den Bekerom MPJ, Eygendaal D (2017) Why does total elbow arthroplasty fail today? A systematic review of recent literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 137(6):761–769

Welsink CL, Lambers KTA, van Deurzen DFP, Eygendaal D, van den Bekerom MPJ (2017) Total elbow arthroplasty: a systematic review. JBJS Rev 5(7):e4

Chen C, Zha YJ, Li T, Jiang XY, Lai LP, Gong MQ (2019) Clinical outcomes of open reduction and internal fixation in treating Gustilo type I and II patients with open distal humeral fractures. Zhongguo Gu Shang 32(4):350–354

Gustilo RB, Anderson JT (1976) Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Jt Surg Am 58(4):453–458

Alonso-Llames M (1972) Bilaterotricipital approach to the elbow. Its application in the osteosynthesis of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Acta Orthop Scand 43(6):479–490

Dubberley JH, Faber KJ, Macdermid JC, Patterson SD, King GJ (2006) Outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of capitellar and trochlear fractures. J Bone Jt Surg Am 88(1):46–54

Elkowitz SJ, Polatsch DB, Egol KA, Kummer FJ, Koval KJ (2002) Capitellum fractures: a biomechanical evaluation of three fixation methods. J Orthop Trauma 16(7):503–506

Clavert P, Ducrot G, Sirveaux F, Fabre T, Mansat P (2013) Outcomes of distal humerus fractures in patients above 65 years of age treated by plate fixation. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res OTSR 99(7):771–777

Lander ST, Mahmood B, Maceroli MA, Byrd J, Elfar JC, Ketz JP et al (2019) Mortality rates of humerus fractures in the elderly: does surgical treatment matter? J Orthop Trauma 33(7):361–365

Frankle MA, Herscovici D Jr, DiPasquale TG, Vasey MB, Sanders RW (2003) A comparison of open reduction and internal fixation and primary total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of intraarticular distal humerus fractures in women older than age 65. J Orthop Trauma 17(7):473–480

Gambirasio R, Riand N, Stern R, Hoffmeyer P (2001) Total elbow replacement for complex fractures of the distal humerus. An option for the elderly patient. J Bone Jt Surg Br 83(7):974–978

Lee KT, Lai CH, Singh S (2006) Results of total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of distal humerus fractures in elderly Asian patients. J Trauma 61(4):889–892

Morrey BF (2000) Fractures of the distal humerus: role of elbow replacement. OrthopClin North Am 31(1):145–154

Huang JI, Paczas M, Hoyen HA, Vallier HA (2011) Functional outcome after open reduction internal fixation of intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly. J Orthop Trauma 25(5):259–265

Korner J, Lill H, Müller LP, Hessmann M, Kopf K, Goldhahn J et al (2005) Distal humerus fractures in elderly patients: results after open reduction and internal fixation. Osteoporos Int 16(Suppl 2):S73–S79

Liu JJ, Ruan HJ, Wang JG, Fan CY, Zeng BF (2009) Double-column fixation for type C fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 18(4):646–651

Plath JE, Forch S, Haufe T, Mayr EJ (2018) Distal humerus fracture in the elderly. Z Orthop Unfall 156(1):30–40

Srinivasan K, Agarwal M, Matthews SJ, Giannoudis PV (2005) Fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly: is internal fixation the treatment of choice? Clin Orthop Relat Res 434:222–230

Pereles TR, Koval KJ, Gallagher M, Rosen H (1997) Open reduction and internal fixation of the distal humerus: functional outcome in the elderly. J Trauma 43(4):578–584

Holdsworth BJ, Mossad MM (1990) Fractures of the adult distal humerus. Elbow function after internal fixation. J Bone Jt Surg Br 72(3):362–365

John H, Rosso R, Neff U, Bodoky A, Regazzoni P, Harder F (1994) Operative treatment of distal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Jt Surg Br Vol 76(5):793–796

Korner J, Lill H, Muller LP, Hessmann M, Kopf K, Goldhahn J et al (2005) Distal humerus fractures in elderly patients: results after open reduction and internal fixation. Osteoporosis Int 16(Suppl 2):S73–S79

Clarke AM (2012) Distal humeral fractures—where are we now? Orthop Trauma 26(5):303–309

Wong AS, Baratz ME (2009) Elbow fractures: distal humerus. J Hand Surg 34(1):176–190

Caravaggi P, Laratta JL, Yoon RS, De Biasio J, Ingargiola M, Frank MA et al (2014) Internal fixation of the distal humerus: a comprehensive biomechanical study evaluating current fixation techniques. J Orthop Trauma 28(4):222–226

Stoffel K, Cunneen S, Morgan R, Nicholls R, Stachowiak G (2008) Comparative stability of perpendicular versus parallel double-locking plating systems in osteoporotic comminuted distal humerus fractures. J Orthop Res 26(6):778–784

Lan X, Zhang LH, Tao S, Zhang Q, Liang XD, Yuan BT et al (2013) Comparative study of perpendicular versus parallel double plating methods for type C distal humeral fractures. Chin Med J (Engl) 126(12):2337–2342

Tian D, Jing J, Qian J, Li J (2013) Comparison of two different double-plate fixation methods with olecranon osteotomy for intercondylar fractures of the distal humeri of young adults. Exp Ther Med 6(1):147–151

Lee SK, Kim KJ, Park KH, Choy WS (2014) A comparison between orthogonal and parallel plating methods for distal humerus fractures: a prospective randomized trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 24(7):1123–1131

Shin SJ, Sohn HS, Do NH (2010) A clinical comparison of two different double plating methods for intraarticular distal humerus fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19(1):2–9

Huang TL, Chiu FY, Chuang TY, Chen TH (2005) The results of open reduction and internal fixation in elderly patients with severe fractures of the distal humerus: a critical analysis of the results. J Trauma 58(1):62–69

Korner J, Diederichs G, Arzdorf M, Lill H, Josten C, Schneider E et al (2004) A biomechanical evaluation of methods of distal humerus fracture fixation using locking compression plates versus conventional reconstruction plates. J Orthop Trauma 18(5):286–293

Obremskey WT, Bhandari M, Dirschl DR, Shemitsch E (2003) Internal fixation versus arthroplasty of comminuted fractures of the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma 17(6):463–465

Kundel K, Braun W, Wieberneit J, Ruter A (1996) Intraarticular distal humerus fractures. Factors affecting functional outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 332:200–208

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical approval

Ethic committee approval: 415-EP/73/633-2016. Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, University Hospital, Salzburg, Paracelsus Medical University, Austria.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moursy, M., Wegmann, K., Wichlas, F. et al. Distal humerus fracture in patients over 70 years of age: results of open reduction and internal fixation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 142, 157–164 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-020-03664-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-020-03664-4