Abstract

Background

Data on the prognostic significance of pacing dependency in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) are sparse.

Methods

The prognostic significance of pacing dependency defined as absence of an intrinsic rhythm ≥ 30 bpm was determined in 786 patients with CIEDs at the authors’ institution using univariate and multivariate regression analysis to identify predictors of all-cause mortality.

Results

During 49 months median follow-up, death occurred in 63 of 130 patients with pacing dependency compared to 241 of 656 patients without pacing dependency (48% versus 37%, hazard ratio [HR] 1.34; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02–1.78, P = 0.04). Using multivariate regression analysis, predictors of all-cause mortality included age (HR 1.07; 95% CI: 1.05–1.08, P < 0.01), history of atrial fibrillation (HR 1.32, 95% CI: 1.03–1.69, P < 0.01), chronic kidney disease (HR 1.28; 95% CI: 1.00–1.63, P = 0.048) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class ≥ III (HR 2.00; 95% CI: 1.52–2.62, P < 0.01), but not pacing dependency (HR 1.15; 95% CI: 0.86–1.54, P = 0.35).

Conclusions

In contrast to age, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease and heart failure severity as indexed by NYHA functional class III or IV, pacing dependency does not appear to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with CIEDs.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Daten zur prognostischen Relevanz der Schrittmacherabhängigkeit bei Patienten mit implantierbaren kardiovaskulären elektrischen Geräten („cardiovascular implantable electronic devices“ [CIED]) sind rar.

Methoden

Die prognostische Relevanz der Schrittmacherabhängigkeit, definiert als Fehlen eines intrinsischen Rhythmus von ≥ 30 Schlägen/min, wurde bei 786 Patienten mit CIED an der Einrichtung der Autoren ermittelt. Hierfür wurden univariate und multivariate Regressionsanalysen durchgeführt, um Prädiktoren der Gesamtmortalität zu identifizieren.

Ergebnisse

In einem medianen Follow-up von 49 Monaten verstarben 63 von 130 Patienten mit Schrittmacherabhängigkeit verglichen mit 241 von 656 Patienten ohne eine solche (48 % vs. 37 %, Hazard Ratio [HR] 1,34; 95 %-Konfidenzintervall [KI] 1,02–1,78, P = 0,04). In einer multivariaten Regressionsanalyse wurden als Prädiktoren der Gesamtmortalität identifiziert: Alter (HR 1,07; 95 %-KI 1,05–1,08, P < 0,01), Vorhofflimmern in der Vorgeschichte (HR 1,32, 95 %-KI 1,03–1,69, P < 0,01), chronische Nierenerkrankung (HR 1,28; 95 %-KI 1,00–1,63, P = 0,048) und New-York-Heart-Association(NYHA)-Klasse ≥ III (HR 2,00; 95 %-KI 1,52–2,62, P < 0,01), nicht aber die Schrittmacherabhängigkeit (HR 1,15; 95 %-KI 0,86–1,54, P = 0,35).

Schlussfolgerungen

Anders als Alter, Vorhofflimmern, chronische Nierenerkrankung und der Schweregrad der Herzinsuffizienz (ausgedrückt durch die NYHA-Funktionsklasse III oder IV) scheint die Schrittmacherabhängigkeit kein unabhängiger Prädiktor der Gesamtmortalität von Patienten mit CIED zu sein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although several previous [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] studies investigated the prevalence of pacing dependency following implantation of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs), only two previous studies [9, 11] determined the prognostic significance of pacing dependency during follow-up. The results of these two previous studies [9, 11], however, remained inconclusive. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to determine the prognostic significance of pacing dependency in a large cohort of 786 patients with CIEDs at the authors’ institution.

Methods

Study population

The study population consisted of 786 patients with a permanent pacemaker or with an implantable defibrillator who were enrolled in the authors’ pacemaker and defibrillator outpatient clinic between January 2018 and December 2018 and who were followed until January 2023 (Fig. 1). Definitions used in this study and baseline characteristics of the study population stratified for patients with and without pacing dependency have been previously published [2]. Briefly, pacemaker dependency was defined as absence of an intrinsic rhythm ≥ 30 bpm after lowering the pacing rate to 30 bpm for at least 10 s or after transient inhibition of pacemaker therapy [2]. Chronic kidney disease of at least stage 3 was diagnosed in the presence of at least two estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula below 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with an interval of at least 3 months. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Philipps-University of Marburg, Germany.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables with normal distribution and median values with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables without normal distribution. Univariate comparisons of clinical characteristics between patients with and without pacemaker dependency were performed using Student’s t‑test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, and categorical values were compared using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to generate a multivariate model including all potential predictors of all-cause mortality during follow-up listed in Tables 1 and 2. All probability values reported are two-sided, and a probability value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. SPSS software version 29 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of 786 study patients are summarized in Table 1 stratified for patients with and without pacing dependency at enrollment. A total of 130 patients (17%) were found to be pacing-dependent, while 656 patients (83%) were not pacing-dependent. The majority of patients were male (65%). Mean age at device implant was 74 ± 13 years. Indication for pacemaker implantation was high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block in 244 patients (31%), sick sinus syndrome in 191 patients (24%), carotid sinus syndrome in one patient (0.1%), and atrial fibrillation with bradycardia in 124 patients (16%). The remaining 232 patients (29%) had no indication for antibradycardia pacing at the time of implantable defibrillator implantation for primary or secondary prevention of sudden death.

Predictors of all-cause mortality during follow-up

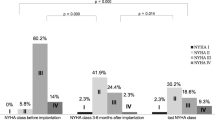

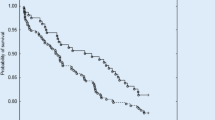

The mean duration of follow-up was 42 ± 16 months (median 49 months; interquartile range 33–53 months). Death during follow-up occurred in 63 of 130 patients with pacing dependency compared to 241 of 656 patients without pacing dependency (48% versus 37%, hazard ratio [HR] 1.34; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02–1.78, P = 0.04). The results of univariate regression analysis of potential predictors of all-cause mortality are summarized in Table 2 and Kaplan-Meier survival curves are shown in Fig. 2. Univariate predictors of all-cause mortality included pacing dependency, age, female gender, arterial hypertension, history of atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 30%, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III or IV, the presence of coronary artery disease, the need for diuretics and the lack of ACE inhibitor or angiotensin blocker therapy (Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier curves for all-cause mortality stratified for: a pacing-dependent patients versus nondependent patients; b patients with a history of atrial fibrillation (AF) versus patients without a history of atrial fibrillation; c patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV versus patients with NYHA class I or II; d patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) versus patients without chronic kidney disease

The results of multivariate regression analysis of potential predictors of all-cause mortality are summarized in Table 3. Multivariate predictors of all-cause mortality included age (HR 1.07; 95% CI: 1.05–1.08, P < 0.01), history of atrial fibrillation (HR 1.32, 95% CI: 1.03–1.69, P < 0.01), chronic kidney disease (HR 1.28; 95% CI: 1.00–1.63, P = 0.048), and NYHA class ≥ III (HR 2.00, 95% CI: 1.52–2.62, P < 0.01). Pacing dependency was not a significant predictor of all-cause mortality using multivariate analysis (HR 1.15, 95% CI: 0.86–1.54, P = 0.35).

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that in the authors’ cohort of 786 patients with CIEDs, independent predictors of all-cause mortality include age, history of atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease and heart failure severity as indexed by NYHA functional class III or IV, but not pacing dependency. Their findings suggest that pacing dependency is merely a marker, but not a predictor for all-cause mortality in patients with CIEDs.

Several previous investigators [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], including the authors’ previous report [2], found a significant association between pacemaker dependency in patients with CIED and second or third degree AV block at implant, age, male gender and heart failure severity as indexed by a higher NYHA functional class, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and elevated brain natriuretic peptide. In addition, a twofold risk for pacemaker dependency in patients with CIED and chronic kidney disease compared to patients without chronic kidney disease was found [2]. Due to the lack of follow-up data, however, most previous studies [2,3,4,5,6,7,8, 10, 12,13,14] investigating the prevalence of pacing dependency in patients with CIEDs did not provide information on whether pacing dependency is an independent prognostic predictor in patients with CIEDs or merely a marker for more advanced heart disease and comorbidities including heart failure and chronic kidney disease.

More than two decades ago, the Dual Chamber and VVI Implantable Defibrillator (DAVID) trial [15] showed that in selected patients with no indication for cardiac pacing and a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, frequent right ventricular pacing had a detrimental prognostic effect by increasing the combined endpoint of death or hospitalization for heart failure. Furthermore, Kiehl et al. [16] described an increased rate of pacing-induced cardiomyopathy also in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction at pacemaker implant in the presence of a right ventricular pacing burden of at least 20% [16]. Subsequently, Khurshid et al. [17] demonstrated that pacing induced-cardiomyopathy could be reversed in the majority of patients by upgrading the pacing system to cardiac resynchronization therapy. In the present study, pacing-dependent patients had a mean amount of ventricular pacing of 98% compared to 36% ventricular pacing in patients without pacing dependency. Despite this high amount of ventricular pacing in pacing-dependent patients, pacing dependency failed to predict all-cause mortality using multivariate analysis in the present study. Raza et al. [9] observed the need for permanent pacemaker implantation for high-degree AV block (55%) or bradycardia (45%) in 141 of 6268 patients after cardiac surgery with a prevalence of pacemaker dependency of 40% in paced patients. Similar to the present study, the mean amount of ventricular pacing was much higher in pacing-dependent patients (91%) compared to nondependent patients (51%). During 5.6-year mean follow-up, Raza et al. [9] found a significant association between permanent pacemaker requirement after surgery and subsequent mortality by univariate analysis but not by multivariate analysis. Of note, Raza et al. [9] compared only the outcomes of patients with and without the need for a permanent pacemaker after surgery. In contrast to the present study, Raza et al. [9] did not perform a subgroup analysis of pacemaker patients with versus without pacing dependency. Sood et al. [11] investigated the prevalence and prognostic significance of pacing dependency in 1058 patients who received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary or secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death during 4.2 years mean follow-up.

Similar to the findings of the authors’ study, Sood et al. [11] found pacing dependency to be associated with older age and a history of atrial fibrillation during follow-up. In contrast to the present study, Sood et al. [11] found pacing dependency to also be associated with a 48% increased risk for all-cause mortality using multivariate analysis, whereas pacing dependency was associated with a 35% increased mortality only by univariate analysis but not by multivariate analysis in the present study. This discrepancy between the study by Sood et al. [11] and this study may in part be explained by differences in study protocol and patient population. First, Sood et al. [11] defined pacemaker dependency as an intrinsic rhythm < 40 beats per minute after inhibiting the pacemaker or an intrinsic rhythm < 50 bpm with transient symptoms of dizziness, whereas pacemaker dependency in the present study was defined as absence of an intrinsic rhythm ≥ 30 bpm after lowering the pacing rate to 30 bpm for at least 10 s or after transient inhibition of pacemaker therapy. Secondly, Sood et al. [11] exclusively investigated patients with implantable defibrillators with a mean left ventricular ejection fraction of 30%, whereas the majority of patients in the present study received permanent antibradycardia pacemakers with a significantly higher mean left ventricular ejection fraction of 43%. Finally, multivariate analysis in this study also included comorbidities like arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and previous cardiac surgery or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. In the authors’ previous report [2] describing the baseline characteristics of pacing-dependent versus nondependent patients, they already found a twofold risk for pacing dependency in patients with CIEDs and chronic kidney disease. Their present follow-up report demonstrates that chronic kidney disease but not pacing dependency is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with CIEDs in addition to older age, history of atrial fibrillation and NYHA functional heart failure class III or IV.

Conclusions

In contrast to age, history of atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease and heart failure severity as indexed by NYHA functional class III or IV, pacing dependency does not appear to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with CIEDs.

References

Yu Z, Liang Y, Xiao Z et al (2022) Risk factors of pacing dependence and cardiac dysfunction in patients with permanent pacemaker implantation. ESC Heart Fail 9:2325–2335

Grimm W, Grimm K, Greene B, Parahuleva M (2021) Predictors of pacing-dependency in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Cardiol J 28:423–430

Glikson M, Dearani JA, Hyberger LK et al (1997) Indications, effectiveness, and long-term dependency in permanent pacing after cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 80:1309–1313

Tang AS, Roberts RS, Kerr C et al (2001) Relationship between pacemaker dependency and the effect of pacing mode on cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 103:3081–3085

Nagatomo T, Abe H, Kikuchi K, Nakashima Y (2004) New onset of pacemaker dependency after permanent pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 27:475–479

Lelakowski J, Majewski J, Bednarek J et al (2007) Pacemaker dependency after pacemaker implantation. Cardiol J 14:83–86

Onalan O, Crystal A, Lashevsky I et al (2008) Determinants of pacemaker dependency after coronary and/or mitral or aortic valve surgery with long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiol 101:203–208

Merin O, Ilan M, Oren A et al (2009) Permanent pacemaker implantation following cardiac surgery: indications and long-term follow-up. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 32:7–12

Raza SS, Li JM, John R et al (2011) Long-term mortality and pacing outcomes of patients with permanent pacemaker implantation after cardiac surgery. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 34:331–338

Rene AG, Sastry A, Horowitz JM et al (2013) Recovery of atrioventricular conduction after pacemaker placement following cardiac valvular surgery. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 24:1383–1387

Sood N, Crespo E, Friedman M et al (2013) Predictors of pacemaker dependence and pacemaker dependence as a predictor of mortality in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 36:945–951

Korantzopoulos P, Letsas KP, Grekas G, Goudevenos JA (2009) Pacemaker dependency after implantation of electrophysiological devices. Europace 11:1151–1155

Feldman S, Glikson M, Kaplinsky E (1992) Pacemaker dependency after coronary artery bypass. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 15:2037–2040

Mar PL, Angus CR, Kabra R et al (2017) Perioperative predictors of permanent pacing and long-term dependence following tricuspid valve surgery: a multicentre analysis. Europace 19:1988–1993

Wilkoff BL, Cook JR, Epstein AE et al (2002) Dual chamber and VVI implantable defibrillator trial investigators. Dual-chamber pacing or ventricular backup pacing in patients with an implantable defibrillator: the Dual Chamber and VVI Implantable Defibrillator (DAVID) Trial. JAMA 288:3115–3123

Kiehl EL, Makki T, Kumar R et al (2016) Incidence and predictors of right ventricular pacing-induced cardiomyopathy in patients with complete atrioventricular block and preserved left ventricular systolic function. Heart Rhythm 13:2272–2278

Khurshid S, Obeng-Gyimah E, Supple GE et al (2018) Reversal of Pacing-Induced Cardiomyopathy Following Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 4:168–177

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

W. Grimm, B. Erdmann, K. Grimm, J. Kreutz and M. Parahuleva declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grimm, W., Erdmann, B., Grimm, K. et al. Prognosis of pacing-dependent patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Herzschr Elektrophys 35, 39–45 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-024-00996-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-024-00996-1

Keywords

- Pacing dependency

- Permanent pacemaker

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- Heart failure

- Chronic kidney disease