Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is accompanied by a high risk of thromboembolic complications necessitating anticoagulation therapy. Arrhythmias have a high tendency to become persistent. Catheter ablation techniques are highly effective in the treatment of AF; however, these procedures are far too costly and time-consuming for the routine treatment of large numbers of AF patients. Moreover, many patients prefer drug treatment although conventional antiarrhythmic drugs are moderately effective and are burdened with severe cardiac and noncardiac side effects. New antifibrillatory drugs developed for the treatment of AF include multichannel blockers with a high degree of atrial selectivity. The rationale of this approach is to induce antiarrhythmic actions only in the atria without conferring proarrhythmic effects in the ventricles.

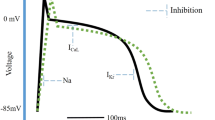

Atrial selective drug action is expected with ion channel blockers targeting ion channels that are expressed predominantly in the atria, i.e., Kv1.5 (IKur), or Kir 3.1 and Kir 3.4 (IK,ACh). Na+ channel blockers that dissociate rapidly may exert atrial selectivity because of subtle differences in atrial and ventricular action potentials. Finally, atrial-selective targets may evolve due to disease-specific processes (e.g., rate-dependent Na+ channel blockers, selective drugs against constitutively active IK,ACh channels).

Zusammenfassung

Vorhofflimmern geht mit einem hohen Risiko für thromboembolische Komplikationen einher, so dass eine Antikoagulationstherapie erforderlich ist. Charakteristisch für diese Arrhythmie ist die große Neigung zur Chronifizierung. Eine hoch effektive Therapieform ist die Katheterablation, allerdings sind die heute üblichen Verfahren viel zu teuer und zeitaufwendig, um damit die große Zahl der Vorhofflimmerpatienten routinemäßig zu versorgen. Trotz der geringeren Wirksamkeit und der hohen Inzidenz von kardialen und extrakardialen Nebenwirkungen konventioneller Antiarrhythmika wünschen viele Patienten zunächst einen medikamentösen Therapieversuch. Neue antifibrillatorische Substanzen mit der Indikation Vorhofflimmern umfassen Multikanalblocker mit einem hohen Ausmaß an Vorhofselektivität. Dieser Therapieansatz beruht auf der Vorstellung, dass beim Vorhofflimmern lediglich die Vorhöfe auf ein Antiarrhythmikum ansprechen sollen. Die Ventrikel benötigen keinen antiarhythmischen Effekt und sollen möglichst überhaupt nicht beeinflusst werden, um das Risiko pro-arrhythmischer Effekte zu vermeiden.

Eine vorhofselektive Wirkung kann von Ionenkanalblockern, die gegen nur im Vorhof exprimierte Kanäle gerichtet sind, erwartet werden, wie z. B. Kv1.5 (IKur), oder Kir 3.1 und Kir 3.4 (IK,ACh). Rasch dissoziierende Na+-Kanalblocker können wegen der elektrophysiologischen Unterschiede zwischen Ventrikel- und Vorhofgewebe ebenfalls eine vorhofselektive Wirkung haben. Und schließlich kann eine vorhofselektive Wirkung aufgrund krankheitsspezifischer Prozesse erzielt werden, z. B. mit frequenzabhängigen Na+-Kanalblockern oder – zumindest theoretisch denkbar – mit selektiven Blockern des konstitutiv aktiven IK,ACh.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC et al (1998) Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med 339:659–666

Wijffels MC, Kirchhof CJ, Dorland R, Allessie MA (1995) Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. A study in awake chronically instrumented goats. Circulation 92:1954–1968

Dobrev D, Ravens U (2003) Remodeling of cardiomyocyte ion channels in human atrial fibrillation. Basic Res Cardiol 98:137–148

Savelieva I, Kourliouros A, Camm J (2010) Primary and secondary prevention of atrial fibrillation with statins and polyunsaturated fatty acids: review of evidence and clinical relevance. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 381:207–219

Van Wagoner DR, Pond AL, Lamorgese M et al (1999) Atrial L-type Ca2+ currents and human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res 85:428–436

Dobrev D, Nattel S (2010) New antiarrhythmic drugs for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Lancet 375:1212–1223

Sun H, Leblanc N, Nattel S (1997) Mechanisms of inactivation of L-type calcium channels in human atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol 272:H1625–H1635

Brundel BJ, Gelder IC van, Henning RH et al (2001) Alterations in potassium channel gene expression in atria of patients with persistent and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: differential regulation of protein and mRNA levels for K+ channels. J Am Coll Cardiol 37:926–932

Carnes CA, Janssen PM, Ruehr ML et al (2007) Atrial glutathione content, calcium current, and contractility. J Biol Chem 282:28063–28073

Christ T, Rauwolf T, Braun M et al (2004) Recording atrial monophasic action potentials using standard pacemaker leads: an alternative way to study electrophysiology properties of the human atrium in vivo? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 27:1632–1637

Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP et al (2002) A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 347:1825–1833

Vaughan Williams EM (1975) Classification of antidysrhythmic drugs. Pharmacol Ther B 1:115–138

Comtois P, Kneller J, Nattel S (2005) Of circles and spirals: bridging the gap between the leading circle and spiral wave concepts of cardiac reentry. Europace 7(Suppl 2):10–20

Allessie MA, Bonke FI, Schopman FJ (1977) Circus movement in rabbit atrial muscle as a mechanism of tachycardia. III. The “leading circle” concept: a new model of circus movement in cardiac tissue without the involvement of an anatomical obstacle. Circ Res 41:9–18

Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB et al (1991) Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. N Engl J Med 324:781–788

Courtemanche M, Ramirez RJ, Nattel S (1998) Ionic mechanisms underlying human atrial action potential properties: insights from a mathematical model. Am J Physiol 275:H301–H321

Wettwer E, Hala O, Christ T et al (2004) Role of IKur in controlling action potential shape and contractility in the human atrium: influence of chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation 110:2299–2306

Van Wagoner DR, Pond AL, McCarthy PM et al (1997) Outward K+ current densities and Kv1.5 expression are reduced in chronic human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res 80:772–781

Bosch RF, Zeng X, Grammer JB et al (1999) Ionic mechanisms of electrical remodeling in human atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 44:121–131

Christ T, Wettwer E, Voigt N et al (2008) Pathology-specific effects of the I(Kur)/I(to)/I(K,ACh) blocker AVE0118 on ion channels in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Br J Pharmacol 154:1619–1630

Ford JW, Milnes JT (2008) New drugs targeting the cardiac ultra-rapid delayed-rectifier current (I Kur): rationale, pharmacology and evidence for potential therapeutic value. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 52:105–120

Dobrev D, Graf E, Wettwer E et al (2001) Molecular basis of downregulation of G-protein-coupled inward rectifying K+ current (IK,ACh) in chronic human atrial fibrillation: decrease in GIRK4 mRNA correlates with reduced I(K,ACh) and muscarinic receptor-mediated shortening of action potentials. Circulation 104:2551–2557

Allessie MA, Lammers WJ, Bonke IM, Hollen J (1984) Intra-atrial reentry as a mechanism for atrial flutter induced by acetylcholine and rapid pacing in the dog. Circulation 70:123–135

Ehrlich JR, Biliczki P, Hohnloser SH, Nattel S (2008) Atrial-selective approaches for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 51:787–792

Dobrev D, Friedrich A, Voigt N et al (2005) The G protein-gated potassium current I(K,ACh) is constitutively active in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation 112:3697–3706

Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Zygmunt AC et al (2007) Atrium-selective sodium channel block as a strategy for suppression of atrial fibrillation: differences in sodium channel inactivation between atria and ventricles and the role of ranolazine. Circulation 116:1449–1457

Siddiqui MA, Keam SJ (2006) Ranolazine: a review of its use in chronic stable angina pectoris. Drugs 66:693–710

Zaza A, Belardinelli L, Shryock JC (2008) Pathophysiology and pharmacology of the cardiac “late sodium current.” Pharmacol Ther 119:326–339

Sossalla S, Kallmeyer B, Wagner S et al (2010) Altered Na(+) currents in atrial fibrillation effects of ranolazine on arrhythmias and contractility in human atrial myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol 55:2330–2342

Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C (2009) Atrial-selective sodium channel block for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 14:233–249

Marrouche NF, Reddy RK, Wittkowsky AK, Bardy GH (2000) High-dose bolus lidocaine for chemical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a prospective, randomized, double-blind crossover trial. Am Heart J 139:E8–E11

Voigt N, Rozmaritsa N, Trausch A et al (2010) Inhibition of I(K,ACh) current may contribute to clinical efficacy of class I and class III antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with atrial fibrillation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 381:251–259

Acknowledgments

The authors receive financial support from Fondation Leducq (07 CVD 03, “Leducq European–North American Atrial Fibrillation Research Alliance”), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Atrial Fibrillation Competence Network, member of the steering committee; New Antiarrhythmic Drugs, Research project 03FPB00226), and the EU FP7-Health-2010-single-stage “EUTRAF”.

Conflict of interest

UR has received grants and honoraria for consulting and lecturing for Cardiome, Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ravens, U., Christ, T. Atrial-selective drugs for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Herzschr. Elektrophys. 21, 217–221 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-010-0088-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-010-0088-8