Abstract

Purpose

Malignant polyps present a treatment dilemma for clinicians and patients. This meta-analysis sought to identify the factors that predicted the management strategy for patients diagnosed with a malignant polyp.

Methods

A literature search was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the Cochrane Collaboration prognostic studies guidelines. Reports from 1985 onwards were included, data on patient and pathological factors were extracted and random effects meta-analysis models were used.

Results

Fifteen studies were included. Seven studies evaluated lymphovascular invasion (LVI). The odds of surgery were significantly higher in malignant polyps with LVI (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.36–3.55). Ten studies revealed the odds of surgery were significantly higher with positive polypectomy margins (OR 8.09, 95% CI 4.88–13.40). Tumour differentiation was compared in eight studies. There were significantly lower odds of surgery in malignant polyps with well/moderate differentiation compared with poor differentiation (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.21–0.46). There were non-significant trends favouring surgical resection in younger patients, males and Haggitt 4/Kikuchi Sm3 lesions. There was considerable heterogeneity in the meta-analyses for the variables age, gender, polyp morphology and Haggitt/Kikuchi level (I2 > 75%).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis has demonstrated that LVI, positive polypectomy resection margins, and poor tumour differentiation significantly predict malignant polypectomy patients who underwent subsequent surgery. Age and gender were important factors predicting management, but not consistently across studies, whilst polyp morphology and Haggitt/Kikuchi levels did not significantly predict the management strategy. Further research may assist in understanding the management preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

Colorectal adenocarcinoma is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers within Australia [1] and worldwide [2]. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence is described as a stepwise progression from normal mucosa, to adenoma, to invasive carcinoma [3]. Early in the process of carcinogenesis, malignancy may be restricted to the polyp, known as a malignant colorectal polyp, or malignant polyp. Malignant polyps are defined as any macroscopically complete endoluminal resection of an adenoma that contains a focus of adenocarcinoma, invading through the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa [4, 5]. Malignant cells must be seen to be invading into the submucosa (thus excluding intramucosal carcinoma). Cancers invading beyond the submucosa (i.e. T2 or higher) are no longer considered malignant polyps. Overall, the literature reports that between 0.75% and 5.6% of all colorectal adenomas contain submucosally invasive adenocarcinoma [6]. Furthermore, an increased incidence of malignant polyps has been noted with the commencement of bowel cancer screening programmes [7].

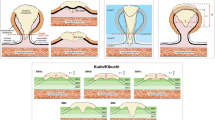

The difficulty in determining the optimal management strategy for malignant polyps lies in the assessment of risk of residual disease in the bowel wall or metastatic lymphatic spread. One of the earliest described factors predicting risk of lymphatic spread was depth of invasion, sub-staged into levels by Haggitt concerning pedunculated polyps [5] and Kikuchi for sessile polyps [8]. Haggitt and Kikuchi levels are shown in Fig. 1. Haggitt reported a significant difference in the rate of adverse events—those being adenocarcinoma spread to draining lymph nodes or mortality due to colorectal cancer—for Haggitt level 4 polyps [5]. Kikuchi reported increased risk of lymph node involvement or an involved resection margin with submucosa (sm) 2 or sm3 level malignant polyps compared with sm1 level malignant polyps [8].

Haggitt and Kikuchi description of level of invasion. Level of invasion as described by Haggitt for a pedunculated polyp (left) and by Kikuchi for a sessile polyp (right). Submucosa (sm) 1 carcinomas invade through the muscularis mucosae to a depth of 200 to 300 μm, Sm2 lies between Sm1 and Sm3, and Sm3 approaches the muscularis propria [4, 7]

In addition to Haggitt and Kikuchi levels, other pathological factors have been identified resulting in higher rates of residual disease or spread to adjacent lymphatics following polypectomy of a malignant polyp. These include poor tumour differentiation, tumour budding, presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and close or involved polypectomy margins and are reflected in guidelines developed by societies of colorectal surgeons, gastroenterologists and pathologists [6, 9, 10]. The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI), American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) recommendations are summarised in Table 1 [6, 9, 11].

The management of a patient diagnosed with a malignant polyp is a dilemma for clinicians. Traditionally, it was felt that as malignant polyps were a cancer, all patients should undergo a segmental lymphovascular colorectal resection, to remove the involved segment of bowel and lymph node basin. However, following segmental resection, only a minority of patients are proved to have residual disease in the bowel wall or metastatic spread to lymph nodes. Furthermore, colorectal surgery is associated with potentially significant complications including anastomotic leak, hospital acquired infections, sexual dysfunction, long-term changes to bowel habits and even death [12, 13]. Therefore, when confronted with the diagnosis of a malignant polyp, clinicians and patients must balance the risks of surgery against the likelihood of residual disease or metastatic spread.

Aim

Whilst guidelines have been developed to suggest when clinicians should consider colorectal resection, this study sought to evaluate which patient pathological factors may influence the management strategy. The aim of this review was to evaluate the literature for the pathological and patient factors that predicted the management strategy for patients with malignant polyps—either colorectal resection or polypectomy with surveillance.

Methods

This systematic review followed the methods and guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [14] and Cochrane Prognosis Methods Group [15] guidelines. This systematic review protocol was published in the PROSPERO Register for Systematic Reviews (CRD42021246504) on 13 May 2021 [16].

Study design and participants

The population of interest were adult patients with a macroscopically complete endoluminal resection of an adenoma that contained a focus of submucosally invasive adenocarcinoma. Endoluminal resection was either via colonoscopic/endoscopic resection or by trans-anal excision of the polyp. Only studies which investigated patients with solitary, sporadic malignant polyps were included.

Exclusion criteria were patients with familial/inherited polyposis syndromes, inflammatory bowel disease, non-adenocarcinoma malignant polyps, polyps with intramucosal carcinoma (T0/carcinoma in situ), T2 or higher tumour stage, multiple malignant polyps or synchronous colorectal malignancy, previous history of colorectal cancer or post neoadjuvant therapy. Additionally, patients who had a malignant polyp that was not amenable to endoluminal resection for diagnosis were considered to have early invasive colorectal cancer and were also excluded. The landmark paper by Haggitt et al. in 1985 was one of the first to clarify the risk of lymph node metastases for malignant polyps [5] and effectively altered the management strategy of malignant polyps. Therefore, only papers published after 1985 were considered for this review.

Systematic literature search

Following consultation with a professional university librarian, a search strategy was devised and performed on 14 May 2021. Web-based databases searched included PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Database and Web of Science. The grey literature was not searched. Search terms included colonic neoplasms, rectal neoplasms, colorectal neoplasms, intestinal polyps, malignant, malignancy, malignancies and/or adenomas. Titles and abstracts of the literature search results were independently assessed by two authors (AZ and NL), and the relevant full texts were obtained. Full text article review was again completed independently by the same two authors. Any disagreements were resolved with discussion, and any disagreement was adjudicated by AR. Published abstracts alone were not included. The reference lists of the reviewed full text articles were appraised for further relevant studies. The risk of bias of the eligible studies was assessed with the QUality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool [17], using the phrase “management strategy” in place of “prognosis”, and “risk factor” replacing “prognostic factor” [17].

Data extraction and outcomes

Recorded study information included study type, numbers of participants, participant selection method and the overall population size. The outcome recorded was the patient’s management strategy. All patient and pathological characteristics for each management strategy were recorded. Meta-analyses were performed using descriptive statistics from each study. Four studies performed statistical analysis using a multivariable model. Overall, the multivariable results appeared very similar to the univariate data; therefore, for consistency only the univariate data was included.

Data synthesis

Random effects meta-analysis models were used to determine how management strategy was affected by the most commonly encountered variables namely: age, gender, polyp location, LVI, margin status, polyp morphology, tumour differentiation and depth of invasion as measured by Haggitt or Kikuchi levels [18]. The effect of categorical variables on management strategy was reported using odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals and 95% prediction intervals. The mean difference in age between management strategy groups was reported with a 95% confidence interval and a 95% prediction interval. For articles which reported no standard deviation [19, 20], estimation of standard deviation was calculated using the method described by Ma et al. [21]. For studies which did not publish a mean or standard deviation, the methods outlined by Wa et al. were applied to estimate a mean and standard deviation of age, assuming a normal distribution for age [22]. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 and a p value. Analyses were performed using Stata v17.0 (STATA, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Included and excluded studies

Figure 2 is the PRISMA diagram summarising the outcome of the literature search and evaluation of studies. Initial literature search identified 1726 studies, 190 were duplicates and removed, a further 1467 were excluded after title and abstract review for not meeting the inclusion criteria of this meta-analysis, leaving 51 full texts that were reviewed. The majority of the 1467 papers excluded from full text review were papers which were investigating topics other than the management strategies of malignant polyps. Fifteen published studies comparing the differing characteristics of patients who were managed with either a polypectomy with surveillance or with surgical resection were identified [7, 19, 20, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34], and these studies are summarised in Table 2. Variables in each study were assessed and documented. The most commonly collected patient and polyp characteristics are documented in Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment

Whilst the QUIPS risk of bias tool is not a perfect fit for this series of meta-analyses, each domain from this tool was considered. For domain 1 (study participation), four studies were assessed as having a moderate risk of bias; a description of patient selection techniques is given in Table 2 [7, 23, 33, 34]. One study was rated at a high risk of bias as there was no description of patient selection techniques [19]. Domain 2 (study attrition), 3 (same measurement of predictors of management for the management strategies) and 4 (management measurement) were of no concern to the studies included in this meta-analysis. The effect of confounding (domain 5) was able to be partially assessed in the four studies which reported a multivariable model [7, 25, 30, 33]. In domain 6 (statistical analysis), five studies did not present descriptive statistics [19, 20, 23, 24, 26]; however, data from these studies were still included in the meta-analyses. Additionally, one other study did not fully report results for three pathological factors; these results are unlikely to affect the result of the meta-analyses (see below) [30].

Meta-analysis results

Patient demographics

Four studies (21061 patients) included data on patient mean age and standard deviation (SD)/standard error (SEM) [7, 25, 28, 32]. The authors of the remaining four studies which reported age data were all contacted to obtain further information regarding the mean age and SD data. This information was received for one additional study [31]. Three studies had their mean and/or SD/SEM estimated [19, 20, 34]. Overall, eight studies (21827 patients) were included [7, 19, 20, 25, 28, 31, 32, 34]. The mean difference in age between the surgical management group and the polypectomy alone group was 1.22 years, which was not significant (95% CI − 0.72–3.42) (Fig. 3A). Nine studies (23763 patients) included patient gender [6, 8, 9, 19, 24, 32, 35,36,37]. The overall OR was 0.92 favouring the odds of surgical resection in males being lower than females; however, this was not significant (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.71–1.18) (Fig. 3B). Both age and gender analyses showed significant heterogeneity between studies, with I2 > 80% and p < 0.001 for heterogeneity in both analyses.

Meta analysis of patient factors that were investigated to predict management plan. The overall result with 95% confidence interval is shown by the green diamond, with the extending lines representing the 95% prediction interval. NB: Gill et al. [30], Levic et al. [28] and Cooper et al. [33] had data comparing age in a categorical format. Gill et al. [30] demonstrated odds of surgery in those < 70 was 2.18 times (95%CI: 1.22–3.87) that of those > 70 years old. Levic et al. [28] demonstrated with chi-squared statistic that management differed between those < 70 and > 70 (p < 0.001). Cooper et al. [33] demonstrated with chi-squared statistic that management strategy was significantly different amongst 5 different age groups (p < 0.001)

Polyp characteristics

Seven studies (913 patients) included the presence of tumour LVI when reporting the management plan [19]. There were significantly higher rates of surgery for patients with polyps with LVI (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.36–3.55) (Fig. 4A). There was negligible heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.3).

Meta analysis of polyp pathological factors that were investigated to predict management plan. Pathological factors that were all investigated by odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were LVI (A), Margins (B), Polyp Morphology (C), Tumour Differentiation (D) and Haggitt/Kikuchi Levels (E). Margins Pos indicates involved or margins within 1 mm. WD/MD indicates cancers that were well or moderately differentiated; poorly indicates cancers that were poorly differentiated. H1–3 indicates patients with Haggitt levels 1–3. Surg/Surgery indicates patients who were managed with a colorectal resection, whilst Polyp/Polypectomy indicates patients who were managed with polypectomy with surveillance. NB: Gill et al. [30] reported that LVI, differentiation and polyp morphology were not found to influence management strategy significantly. However, Gill et al. did not present their summary data, and so the study was not included these meta-analyses. Estimating the raw data, with an odds ratio of 1, did not significantly influence the outcomes of these meta-analyses

Ten studies (1762 patients) evaluated positive or close margins [19, 23, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 34]. There were differing definitions of positive margin status; therefore, to maximise the numbers of patients included in the statistical analysis, positive margins were considered together with close margins, meaning the presence of tumour cells within 1 mm of the polypectomy margin was included together. This definition is consistent with management guidelines [6]. The rate of surgery was significantly higher for those with positive or close margins (OR 8.09, 95% CI 4.88–13.40) (Fig. 4B). There was a moderate degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 64%, p = 0.003).

Ten studies (1933 patients) evaluated the type of polyp (pedunculated vs sessile) [19, 23, 25,26,27,28,29, 31, 32, 34]. The pooled odds ratio was not significant when comparing patient management based upon whether the polyp was pedunculated or sessile (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.35–1.87) (Fig. 4C). There was a high degree of heterogeneity amongst studies (I2 = 92%, p < 0.001).

Eight studies (2224 patients) included data on tumour differentiation [23, 26,27,28,29, 31, 33, 34]. Well/moderately differentiated tumours were compared to poorly differentiated tumours. The overall odds of surgery were significantly lower in those with well differentiated or moderately differentiated tumours compared to poorly differentiated tumours (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.21–0.46) (Fig. 4D). There was negligible heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.64).

Whilst five studies assessed Haggitt or Kikuchi levels, one study grouped Haggitt/Kikuchi levels differently [34], and inclusion in the meta-analysis was not possible for this study. Across the remaining four studies (344 patients) [24, 28, 30, 31], a trend towards polypectomy and surveillance for patients with Haggitt level 1–3 or Kikuchi Sm1-2 level invasion was observed but was not statistically significant (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.10–1.99) (Fig. 4E). There was a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 77%, p = 0.005).

Mucinous differentiation was only reported in 2 studies, precluding its assessment in a meta-analysis [28, 34]. Likewise, tumour budding was only reported in 4 studies [27, 28, 32, 34], with one study only reporting budding status for a single patient [27]; thus, tumour budding was not assessed in a meta-analysis.

Discussion

These meta-analyses assessed patient and pathological factors which predicted patient management. This is the first series of meta-analyses directly assessing the factors which predict the management strategy for malignant colorectal polyps. The key findings were that LVI, close or positive margins and poorly differentiated tumours all had a statistically significant higher odds of proceeding to surgery over polypectomy and surveillance. Conversely, age, gender, polyp type and a Haggitt/Kikuchi assessment of depth of invasion did not have statistically significantly different odds of proceeding to surgery post polypectomy.

This review investigated four of the six pathological factors, suggested by the ACPGBI guidelines, which may affect the management strategy. LVI, poor differentiation and close or involved tumour polypectomy margins were all significant predictors of resection. The presence of LVI in a polypectomy specimen has previously been reported to be associated with an increased risk of metastatic lymphatic disease [38]. Likewise, poor differentiation has been associated with an increased risk of residual disease and lymphatic spread [4]. Finally, close or positive margins present a logical risk of residual disease [6]. Thus, LVI, poor differentiation and close or involved polypectomy margins all increase the risk of residual or metastatic disease, and ACPGBI guidelines suggest colorectal resection as the appropriate management strategy. These meta-analyses suggest that the ACPGBI recommendations are being followed in practice [6].

Whilst clinical guidelines suggest patients with a Haggitt level 4 or Kikuchi level Sm3 malignant polyps should be considered for resection, this was not statistically reflected in this meta-analysis. However, it must be noted that this pathology detail was not commonly recorded and represented only a minority of the total patient cohort across all studies. Furthermore, even in studies which contained data on Haggitt/Kikuchi levels, there were large numbers of study patients without a Haggitt or Kikuchi level recorded [28]. There may be pathological reasons that Haggitt or Kikuchi levels were unable to be included in histopathological reports. These may include incomplete polypectomy, fragmented polypectomy specimens and difficulty determining polyp morphology when ex situ. It is noted that pathological reporting is increasingly moving towards quantitative reporting of depth of invasion in millimetres, either in addition to or instead of a Haggitt or Kikuchi level [10]. Future studies investigating management decisions for malignant polyps should consider collecting this direct measure of depth of invasion. Of the fifteen studies in this meta-analysis, only one contained this measurement [34]. Depth of invasion, whether measured as a Haggitt/Kikuchi level, or as a direct measure of invasion below the muscularis mucosae has been significantly associated with lymphatic and residual disease [5, 8, 38, 39]. However, depth of invasion may not always be reported in an interpretable format in pathological reporting, and this was highlighted in this meta-analysis. It is likely that the lack of this information in the published literature, reflects current clinical practice and histopathological reports. As depth of invasion plays an important role in estimation of the risk of residual or lymphatic disease, clinicians may be warranted in insisting on an estimate of depth of invasion, to provide patients with the best estimate of risk of residual or lymphatic disease.

The ACPGBI scoring system for determining a recommended management strategy for malignant polyps also considers the pathological factors of the presence of mucinous differentiation and tumour budding [6]. Both mucinous differentiation and tumour budding were unable to be assessed in this meta-analyses due to the small number of studies including these pathological parameters.

When comparing demographic characteristics, there were no significant differences in the age or gender of patients with malignant polyps when comparing polypectomy alone with surgical management. It would be anticipated that older patients would be at higher risk of surgical morbidity and mortality, and might be less likely to proceed to surgery. Despite the trend towards a younger age for patients undergoing surgery, this was not statistically significant.

There existed significant heterogeneity within some of the meta-analyses that were performed in this review (Figs. 3 and 4). Since 1985 there have been significant changes in patient expectations, operative techniques and anaesthetic practice. The variable adoption over time of these practices across the different surgical departments have likely contributed significantly to the heterogeneity seen in these meta-analyses (Table 2).

One limitation in this series of meta-analyses was the inability to compare an overall risk of individual malignant polyps between the polypectomy and surgical resection groups. There is the potential that some studies could have featured a high number of patients with a single high-risk pathological factor which encouraged clinicians to consider colorectal surgical resection. As such other high-risk pathological factors may not have been present, yet the patient still proceeded to surgery, potentially introducing a source of bias in these results. However, it is noted that often high-risk features for residual or metastatic disease appear concurrently, such as greater depth of invasion and LVI [40] and so reducing this potential of bias. The ACPGBI guidelines combine all risk factors into a summary score of risk. No study identified in this review directly compared the ACPGBI risk categories between management strategies. Future research should consider using a known published risk categorisation tool, such as the one published by the ACPGBI to reduce this risk of bias. Another limitation of this review was the diverse patient and polyp factors collected or reported. Guidelines clearly document indications for clinicians to consider surgical resection; however, this study found that few patient characteristics were reported to understand why patients underwent surveillance, when guidelines would recommend surgical management. It would have been of interest to evaluate patient comorbidities that may influence patient selection for surgical resection. A surrogate of patient comorbidities is the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) Score, which grades patients based upon their pre-operative comorbidities [41]. Thus, it was considered whether a patient ASA could be assessed in a meta-analysis. However, the ASA was only reported in three studies, thus limiting the ability to analyse this important determinant.

Further research should focus on understanding the decision-making process to arrive at polypectomy and surveillance versus surgery. Whilst LVI, margin status and poor differentiation were shown to be a predictor of surgery, there were still a number of patients with these pathological features, who did not undergo surgical resection. Patient choice, comorbidities or clinician lack of familiarity with malignant polyp guidelines may explain why these patients did not undergo resection. Pathological factors associated with increased risk of lymphatic spread, such as Haggitt or Kikuchi levels, were commonly not reported. The reasons for this under-reporting would be of interest to further research and quality improvement activities. Further strategies to educate clinicians and patients on their risk of residual or metastatic disease, in the setting of a malignant polyp, may be helpful. Lastly, comparison of overall malignant polyp risk, in the comparison of ACPGBI risk categories, between management strategies would reduce the risk of bias in future studies.

Conclusion

The management of malignant polyps remains a treatment dilemma. This is the first known meta-analysis evaluating the factors guiding the management strategy for patients with malignant polyps. From the fifteen studies evaluated, the presence of LVI, positive or close margins and poorly differentiated tumours were all significantly associated with patients undergoing a colorectal segmental resection. Whilst Haggitt/Kikuchi level was not statistically significantly associated with patients undergoing a colorectal resection, this assessment was limited by high heterogeneity and limited numbers in the studies assessed. Further population-based analysis would assist in understanding the actual management preferences and adherence to guidelines for malignant polyps in the wider community.

References

Cancer Australia (2021) Bowel Cancer. Australian Government. https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/affected-cancer/cancer-types/bowel-cancer/bowel-cancer-colorectal-cancer-australia-statistics. Accessed 7 May 2021

Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A (2019) Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol 14(2):89–103. https://doi.org/10.5114/pg.2018.81072

Fearon ER, Vogelstein B (1990) A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 61(5):759–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i

Hassan C, Zullo A, Risio M, Rossini FP, Morini S (2005) Histologic risk factors and clinical outcome in colorectal malignant polyp: a pooled-data analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 48(8):1588–1596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-005-0063-3

Haggitt RC, Glotzbach RE, Soffer EE, Wruble LD (1985) Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinomas arising in adenomas: implications for lesions removed by endoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology 89(2):328–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(85)90333-6

Williams JG, Pullan RD, Hill J, Horgan PG, Salmo E, Buchanan GN, Rasheed S, McGee SG, Haboubi N (2013) Association of Coloproctology of Great B, Ireland, Management of the malignant colorectal polyp: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Dis 15(Suppl 2):1–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12262

Wasif N, Etzioni D, Maggard MA, Tomlinson JS, Ko CY (2011) Trends, patterns, and outcomes in the management of malignant colonic polyps in the general population of the United States. Cancer 117(5):931–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25657

Kikuchi R, Takano M, Takagi K, Fujimoto N, Nozaki R, Fujiyoshi T, Uchida Y (1995) Management of early invasive colorectal cancer. Risk of recurrence and clinical guidelines. Dis Colon Rectum 38(12):1286–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02049154

Shaukat A, Kaltenbach T, Dominitz JA, Robertson DJ, Anderson JC, Cruise M, Burke CA, Gupta S, Lieberman D, Syngal S, Rex DK (2020) Endoscopic recognition and management strategies for malignant colorectal polyps: recommendations of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 92(5):997–1015 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2020.09.039

The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia (2020) Polypectomy and Local Resections of the Colorectum Structured Reporting Protocol (2nd Edition 2020). Sydney, Australia. Available from: https://www.rcpa.edu.au/getattachment/777b2f36-3b54-4d97-94c0-040a31f97b2b/Protocol-Polypectomy-local-resections-CR.aspx. Acceseed 1 Dec 2021

Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hasegawa K, Hotta K, Ishida H, Ishiguro M, Ishihara S, Kanemitsu Y, Kinugasa Y, Murofushi K, Nakajima TE, Oka S, Tanaka T, Taniguchi H, Tsuji A, Uehara K, Ueno H, Yamanaka T, Yamazaki K, Yoshida M, Yoshino T, Itabashi M, Sakamaki K, Sano K, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Uetake H, Yamaguchi S, Yamaguchi N, Kobayashi H, Matsuda K, Kotake K, Sugihara K, Japanese Society for Cancer of the C, Rectum (2020) Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 25(1):1–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-019-01485-z

Giglia MD, Stein SL (2019) Overlooked long-term complications of colorectal surgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 32(3):204–211. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1677027

Kirchhoff P, Clavien PA, Hahnloser D (2010) Complications in colorectal surgery: risk factors and preventive strategies. Patient Saf Surg 4(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-9493-4-5

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Moons C, Hooft L, Damen A (2018) Introducing systematic reviews of prognosis studies to Cochrane: Cochrane Collaboration. https://training.cochrane.org/resource/introducing-systematic-reviews-prognosis-studies-cochrane-what-and-how. Accessed September 17

Zammit AP, Lyons N, Hooper J, Brown I, Clark D, Riddell A (2021) Adverse histological features or clinical considerations predicting segmental resection after endoscopic removal of malignant colorectal polyps: a systematic review. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=246504. Accessed 28 May 2021

Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C (2013) Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 158(4):280–286. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7(3):177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

Cunningham KN, Mills LR, Schuman BM, Mwakyusa DH (1994) Long-term prognosis of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in endoscopically removed colorectal adenomas. Dig Dis Sci 39(9):2034–2037. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02088143

Sharma V, Junejo MA, Mitchell PJ (2020) Current management of malignant colorectal polyps across a regional United Kingdom Cancer Network. Dis Colon Rectum 63(1):39–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000001509

Ma J, Liu W, Hunter A, Zhang W (2008) Performing meta-analysis with incomplete statistical information in clinical trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 8:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-56

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T (2014) Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

Wu XR, Liang J, Church JM (2015) Management of sessile malignant polyps: is colonoscopic polypectomy enough? Surg Endosc 29(10):2947–2952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-4027-3

Whitlow C, Gathright JB Jr, Hebert SJ, Beck DE, Opelka FG, Timmcke AE, Hicks TC (1997) Long-term survival after treatment of malignant colonic polyps. Dis Colon Rectum 40(8):929–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02051200

Senore C, Giovo I, Ribaldone DG, Ciancio A, Cassoni P, Arrigoni A, Fracchia M, Silvani M, Segnan N, Saracco GM (2018) Management of Pt1 tumours removed by endoscopy during colorectal cancer screening: outcome and treatment quality indicators. Eur J Surg Oncol 44(12):1873–1879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.09.009

Netzer P, Binek J, Hammer B, Lange J, Schmassmann A (1997) Significance of histologic criteria for the management of patients with malignant colorectal polyps and polypectomy. Scand J Gastroenterol 32(9):910–916. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365529709011201

Levic K, Kjær M, Bulut O, Jess P, Bisgaard T (2015) Watchful waiting versus colorectal resection after polypectomy for malignant colorectal polyps. Dan Med J 62(1):A4996

Levic K, Bulut O, Hansen TP, Gögenur I, Bisgaard T (2019) Malignant colorectal polyps: endoscopic polypectomy and watchful waiting is not inferior to subsequent bowel resection. A nationwide propensity score-based analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 404(2):231–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-018-1706-x

Goncalves BM, Fontainhas V, Caetano AC, Ferreira A, Goncalves R, Bastos P, Rolanda C (2013) Onco logical outcomes after endoscopic removal of malignant colorectal polyps. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 105(8):454–461. https://doi.org/10.4321/s1130-01082013000800003

Gill MD, Rutter MD, Holtham SJ (2013) Management and short-term outcome of malignant colorectal polyps in the north of England. Colorectal Dis 15(2):169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03130.x

Fischer J, Dobbs B, Dixon L, Eglinton TW, Wakeman CJ, Frizelle FA (2017) Management of malignant colorectal polyps in New Zealand. ANZ J Surg 87(5):350–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.13502

Fasoli R, Nienstedt R, De Carli N, Monica F, Guido E, Valiante F, Armelao F, de Pretis G (2015) The management of malignant polyps in colorectal cancer screening programmes: a retrospective Italian multi-centre study. Dig Liver Dis 47(8):715–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2015.04.011

Cooper GS, Xu F, Barnholtz Sloan JS, Koroukian SM, Schluchter MD (2012) Management of malignant colonic polyps: a population-based analysis of colonoscopic polypectomy versus surgery. Cancer 118(3):651–659. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26340

Brown IS, Bettington ML, Bettington A, Miller G, Rosty C (2016) Adverse histological features in malignant colorectal polyps: a contemporary series of 239 cases. J Clin Pathol 69(4):292–299. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203203

Ugenti I, Martines G, Andriola V, de Marinis EC, Caputi Iambrenghi O (2019) Factors affecting long-term outcome of patients treated for malignant colorectal polyps: endoscopic versus surgical treatment. A single center experience. Chirurgia (Turin) 32(4):166–71. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0394-9508.18.04851-9

Statistics Denmark (2021) Population in Denmark. https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/emner/befolkning-og-valg/befolkning-og-befolkningsfremskrivning/folketal. Accessed 18/06/2021

Lowe D, Saleem S, Arif MO, Sinha S, Brooks G (2020) Role of endoscopic resection versus surgical resection in management of malignant colon polyps: a National Cancer Database Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 24(1):177–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04356-0

Kitajima K, Fujimori T, Fujii S, Takeda J, Ohkura Y, Kawamata H, Kumamoto T, Ishiguro S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, Iwashita A, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Watanabe T, Muto T, Nagasako K (2004) Correlations between lymph node metastasis and depth of submucosal invasion in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma: a Japanese collaborative study. J Gastroenterol 39(6):534–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-004-1339-4

Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Hashiguchi Y, Shimazaki H, Aida S, Hase K, Matsukuma S, Kanai T, Kurihara H, Ozawa K, Yoshimura K, Bekku S (2004) Risk factors for an adverse outcome in early invasive colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 127(2):385–394. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.022

Tytherleigh MG, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ (2008) Management of early rectal cancer. Br J Surg 95(4):409–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6127

Mayhew D, Mendonca V, Murthy BVS (2019) A review of ASA physical status—historical perspectives and modern developments. Anaesthesia 74(3):373–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14569

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. AZ is supported through the Professor Philip Walker Research Scholarship administered through the University of Queensland. No other funding was obtained for completion of this review and meta-analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Article idea formulation: AZ, JD, IB, DC, AR; literature search and article screening: AZ, NL; data analysis: AZ, MC; draft writing of article: AZ; critically revised the work: NL, MC, JH, IB, DC, AR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

As outlined in the review below, this meta-analysis was registered in the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews on the 13/05/2021: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=246504

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zammit, A.P., Lyons, N.J., Chatfield, M.D. et al. Patient and pathological predictors of management strategy for malignant polyps following polypectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 37, 1035–1047 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-022-04142-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-022-04142-6