Abstract

Multidimensional welfare analysis has recently been revived by money-metric measures based on explicit fairness principles and the respect of individual preferences. To operationalize this approach, preference heterogeneity can be inferred from the observation of individual choices (revealed preferences) or from self-declared satisfaction following these choices (subjective well-being). We question whether using one or the other method makes a difference for welfare analysis based on income-leisure preferences. We estimate ordinal preferences that are either consistent with actual labor supply decisions or with income-leisure satisfaction. For ethical priors based on the compensation principle, we compare the welfare rankings obtained with both methods. The correlation in welfare ranks is high in general and reranking is insignificant for 77% of the individuals. The remaining discrepancies possibly pertain to a variety of factors including constraints (health issues, labor market rationing), irrational behavior and alternative life choices to the pursuit of well-being. We discuss the implications of using one or the other preference elicitation method for welfare analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The bulk of this literature has assumed that individuals only differ in their abilities but have identical preferences otherwise (Boadway 2012). Importantly, recent developments in optimal taxation have suggested to respect preference heterogeneity using fair allocation principles (Schokkaert et al. 2004; Jacquet and Van de Gaer 2011; Fleurbaey and Maniquet 2006, 2007, 2014).

Decancq et al. (2014) suggest a method to construct money metric evaluation of “the good life”, incorporating many dimensions beyond income, based on subjective data. Schokkaert et al. (2011) focus on income and job satisfaction. Decancq and Schokkaert (2013) and Decancq et al. (2015) follow similar approaches while focusing on social progress and poverty respectively. Jara and Schokkaert (2017) assess tax reforms using SWB or equivalent income derieved from SWB.

The first explicit comparison has been suggested by Benjamin et al. (2012, 2014a, b), who proxy experienced utility using SWB and decision utility using stated or actual preferences in tailor-made studies. Regarding a broad range of life choices, Fleurbaey and Schwandt (2015) ask people if they can think of changes that would increase their SWB score. Akay et al. (2015) use large microdata to compare labor supply decisions and income-leisure SWB on average. Considering own income versus others’ income, Clark et al. (2015) find similar relative concerns in happiness regressions and in hypothetical-choice experiments. Arguably, more divergence is found in other recent studies based on job satisfaction (Ferrer-i Carbonell et al. 2010), residential choice (Glaeser et al. 2016) or consumption (Perez-Truglia 2015).

On the revealed preference side, to recover individual ordinal preferences requires the full identification of a collective model of labor supply with nonlinear taxation, which has very rarely been done (see Chiappori and Donni 2011). Some of the rare attempts—Lise and Seitz (2011) and Bloemen (2018)—focus mainly on the sharing rule, which can be seen as a specific form of money metric utility. On the SWB side: one would need to recover individual income-leisure satisfaction within couples. However, when answering the income satisfaction question, it is unclear whether the wife (husband) expresses her (his) satisfaction about the household’s total budget or whether she (he) talks about the resources available to her (him) in the household. Only the latter is the appropriate measure, to be put against her (his) level of leisure, to measure female (male) income-leisure preferences.

Information on mental health is also available (namely the index from the General Health Questionnaire GHQ-12) as well as answers to the happiness question. These alternative SWB measures lead to relatively similar results regarding the estimation of ordinal income-leisure preferences (see Akay et al. 2015).

Importantly, note that hours of work and gross income (used to compute disposable income) refer to the last week while subjective well-being indices correspond to the date of interview.

We use above-average dummies for ease of interpretation. Note that among the different personality traits, conscientiousness and neuroticism are shown to be what matters the most for labor supply choices (see Wichert and Pohlmeier 2010). Neuroticism is a fundamental personality trait in the study of psychology characterized by anxiety, fear, moodiness, worry, envy, frustration, jealousy, and loneliness. Conscientiousness is the personality trait of being thorough, careful, or vigilant, implying the desire to do a task well.

Observed heterogeneity \(z_{it}\) includes gender, age (and age squared), education, health status, presence of children aged 0–2, living in London, non-white ethnic origin, migrant, family size, home ownership, region and year. Remark that some of these variables are allowed here to have a direct effect on SWB but also enter in income-leisure preference heterogeneity.

Note also that at least three types of unobserved variables may limit the possibility of interpersonal comparability of SWB (see Fleurbaey and Blanchet 2013): (i) omitted variables that make people perceive and interpret SWB scales differently, (ii) omitted personality traits that make them respond differently or adapt differently to their own conditions (e.g. the resilient poor—see the idea of ‘physical-condition neglect’ in Sen (1985)—or the grumpy rich, etc.), (iii) measurement errors. We assume that individual fixed effects—or a proxy based on time-invariant personality traits, in our case—can capture some of these unobservables and improve comparability.

We use a relatively thin discretization with \(J=7\) options corresponding to weekly work hours from 0 (inactivity) to 60 (overtime), with a step of 10 hours. For each option j, we specify decision utility as a function of (discrete) leisure \(l_{ijt}\) and income \(y_{ijt}\). The latter is simulated as a function of the gross earnings generated when working \(h_{ijt}=\tau -l_{ikt}\) hours and taking into account the taxes paid and benefits received at that income level (see Appendix A). Maximum available time \(\tau \) is set to 80 h per week in our application.

This is a rather strong assumption made for practical reasons here (and in line with the long tradition of second-best optimal policy design). Hourly wages depend, to some extent, on past decisions regarding the accumulation of human capital and, hence, on individual preferences and past efforts.

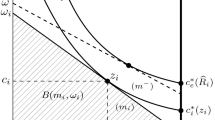

More generally, it is defined as a ‘min criterion’, i.e. the unearned income that would suffice if working did not bring any wage. This metric is extensively discussed in Fleurbaey and Blanchet (2013, Appendix A3).

Because the derivation of welfare metrics requires tangency conditions, indifference curves must be based on the deterministic part of utility functions (see Appendix A1 about the respect of monotonicity and concavity in the empirical application). This is not an issue for subjective preferences: random terms \(\eta _{it}^{E}\) do not vary with hour alternatives, and metrics can be calculated at the observed choice so that \( \overline{u}^{E}=\widehat{u}_{i}^{E} \left( y^{obs},l^{obs}\right) \). For revealed preferences, as indicated above, stochastic components \(\eta _{ijt}^{D}\) are unobserved attributes of work alternatives j (discrete choice formulation) and explain why certain hour options are sometimes chosen despite not yielding the highest deterministic utility. The probabilistic nature of the model leads to a frequency distribution of hour choices (rather than to a perfect prediction of the observed choice), which is taken into account when calculating the metrics. We simply calculate \( \overline{u}^{D}\) as an average utility over the discrete hour alternatives weighted by their estimated probabilities. Similar approaches are also possible. Decoster and Haan (2015) calculate the welfare metric at each discrete hour, and average over all hours using estimated hour probabilities as weights. Bargain et al. (2013) compute the expected utility over many draws of the sets of EV-I terms, keeping each time the utility level attained at the optimal choice. A sensitivity analysis by these authors shows that the different methods lead to very similar welfare orderings.

Other sources of bias may relate to different treatments of the random terms, which, by construction, cannot be perfectly symmetrical in the two approaches. Also, we extensively discuss in Appendix A the fact that preference estimations based either on behavior or SWB may be biased by unobservables. We use several tools to address this issue: spatial and temporal variation in net wages, taste-shifters including psychological traits, random preference-for-leisure parameters. Still, one can never exclude that remaining biases cause some of the observed differences between preferences derived from both methods.

We have also tried more flexible specifications than the linear form in Eq. (1), namely the addition of interaction terms between \( S_{it}^{y}\) and \(S_{it}^{l}\) (the coefficient of which proved insignificant) and/or quadratic terms. The results are again very similar (unreported).

The bias-correction procedure increases the variance of the estimator, but our sample size is sufficiently large for this to be negligible.

Using panel information, we find a correlation of 0.80 between an absolute welfare measure (i.e. before taking ranks) and its lag. Hence, in the extreme case where time variation was entirely due to errors, the error variance would be around 20% of the variance of the observed welfare measures.

Another aspect is the role of dynamics and forward-looking decisions, including intertemporal substitution in labor supply choices (e.g. work harder now to save for a future time when productivity declines). The structural models used to retrieve revealed and subjective preferences are both static. Thus, the labor supply model can be seen as misspecified or based on strong (intertemporal separability) assumptions. The SWB model can also be characterized as misspecified if the current situation only partly correlates with instantaneous income-leisure satisfaction (i.e. if people who currently work hard and earn a little are nevertheless happy because they think prosperity is around the corner). Yet, SWB often pertains to myopic attitudes. Several studies attempt to show the extent to which people make systematic prediction errors regarding the future impact of choices/events on their life satisfaction, partly because of unforeseen adaptation (Loewenstein et al. 2003; Frijters 2000; Frijters et al. 2009; Benjamin et al. 2012; Odermatt and Stutzer 2015).

Hamermesh and Slemrod (2008) point to workaholism as an issue affecting the high skilled primarily, generated by biased beliefs about the well-being effects of work. Loewenstein et al. (2003) argue that individuals fail to appreciate how habit formation will affect future preferences and show that such a ‘projection bias’ might create a tendency to repeatedly increase labor and decrease leisure relative to earlier plans.

The individual responsibility regarding these possibly inherited conditions is again a difficult question. Trannoy (2016) writes: “In the lifespan, maybe we can claim that the degrees of freedom of an individual are more important but still the analyst has to cope with the dependency of the trajectory of the individual to initial conditions. An individual starting with a long spell of unemployment just due to bad luck will have a stigma which will take time to be rubbed out.”

The UK is often described as a country with little support for maternal employment due to little public childcare provision, pushing maternal workforce into inactivity or low paid part-time employment (see Viitanen 2005, for instance).

In particular, Decancq and Neumann (2015) confront a variety of measures of the “good life”. They show a high degree of reranking, and almost no correlation in the definitions of the worst off, when using current measures available in the literature. Decancq et al. (2015) for Russia also find low overlap between worst-off definitions according to income, life satisfaction and equivalent income. Given our previous results and the fact that we focus on a bidimensional welfare measure (income-leisure), we expect to find more overlap than in these studies. Carpantier and Sapata (2016) are in a similar situation. They also focus on income-leisure preferences, using the revealed preference approach only but a larger variety of fairness criteria. They find a great overlap in the identity of the worst-off across these criteria.

The normative debate about whether these preferences are justified or not—for instance inherited from ‘bad’ labor market equilibria—is open. Yet imposing subjective well-being as a norm seems equally arbitrary.

This is in line with Fleurbaey and Maniquet (2014) who suggest that if work aversion is partly due to non-responsibility factors, for instance low job quality (unpleasant, dangerous, etc.) for the unskilled, it may be “prudent or charitable” to choose a low value for the equivalent wage. After all, involuntary under-work may be viewed as reducing the agents’ earning ability (Fleurbaey and Maniquet 2006).

The Laissez–Faire principle underlying the Wage metric is acceptable if individual preferences are fully respectable. This is not the case if they reflect external factors (e.g. constraints) but more debatable in cases discussed above (e.g. moral obligation to support relatives, workaholism due to social pressure, etc.).

In the present study, we have discarded job seekers—deemed as involuntary unemployed—from the analysis. Nonetheless, labor constraints are still present among part-timers and involuntarily idle workers (e.g. discouraged workers or single mothers facing zero or negative gains from work). As noted, a fundamental difficulty is to identify demand-side and institutional constraints on the basis of standard characteristics observed in survey data. Exclusion restrictions are never satisfying, and more (quasi)experimental variation should be used in order to recover actual preference parameters. Recent approaches characterize frictions by comparing long term and short term adjustments, assuming people are less constrained in the long run (Chetty 2012). Some studies have explicitly accounted for labor market rationing within labor supply models, for instance by modelling the probability of involuntary unemployment (e.g., Haan and Uhlendorff 2013), the demand-side of the labor market (Peichl and Siegloch 2012) or the distribution of job opportunities (see a modern account in Beffy et al. 2016, and Capéau et al. 2016). It is difficult, however, to account for all these aspects simultaneously—and the range of ‘constraints’ may be large: discrimination, rationing (e.g. productivity below minimum wage), frictional unemployment, discouragement, low-quality jobs, wrong belief about job opportunities, etc. As for work costs, they are also typically not identified on the basis of standard observed characteristics (cf. van Soest et al. 2002).

In further work, more systematic characterization of these SWB-revealed frictions could be obtained for different countries and points in time in order to check if they are indeed correlated with the business cycle (ex: larger frictions in times of strong demand-side constraints).

The fact that these metrics need not satisfy the Pigou-Dalton principle everywhere is not necessarily a strong argument against using them to construct a social welfare function that is less extreme than the maximin. Indeed, the violation of the Pigou-Dalton principle occurs only when indifference curves change shape when utility increases, in a way that makes the violation of the principle not so shocking.

An assessment of the box-cox functional form for labor supply behavior, compared to more flexible specifications, is suggested by Dagsvik and Strøm (2006).

References

Akay A, Bargain O, Jara HX (2015) Back to bentham, should we? Large-scale comparison of experienced versus decision utility, ISER discussion paper

Bargain O, Decoster A, Dolls M, Neumann D, Peichl A, Siegloch S (2013) Welfare, labor supply and heterogeneous preferences: evidence for Europe and the US. Soc Choice Welf 41(4):789–817

Bargain O, Orsini K, Peichl A (2014) Labour supply elasticities: a complete characterization for Europe and the US. J Hum Resour 49(3):723–838

Beffy M, Blundell R, Bozio A, Laroque G, To M (2016) Labour supply and taxation with restricted choices. IFS working paper 15/02

Benjamin D, Heffetz O, Kimball M, Rees-Jones A (2012) What do you think would make you happier? What do you think you would choose? Am Econ Rev 102(5):2083–2110

Benjamin D, Heffetz O, Kimball M, Rees-Jones A (2014a) Can marginal rates of substitution be inferred from happiness data? Evid Resid Choice Am Econ Rev 104:3498–3528

Benjamin D, Heffetz O, Kimball M, Szembrot N (2014b) Beyond happiness and satisfaction: toward well-being indices based on stated preference. Am Econ Rev 104(9):2698–2735

Bernheim D, Rangel A (2009) Beyond revealed preference: choice theoretic foundations for behavioral welfare economics. Q J Econ 124(1):51–104

Blackorby C, Donaldson D (1988) Money metric utility: a harmless normalization. J Econ Theory 46:120–129

Bloemen HG (2018) Collective labour supply, taxes, and intrahousehold allocation: an empirical approach. J Bus Econ Stat

Blundell R, Duncan A, McCrae J, Meghir C (2000) The labour market impact of the working families’ tax credit. Fiscal Stud 21(1):75–103

Blundell R, Duncan A, Meghir C (1998) Estimating labor supply responses using tax reforms. Econometrica 66(4):827–861

Boadway R (2012) Review of ’A Theory of Fairness and Social Welfare’ by Fleurbaey and Maniquet. J Econ Lit 50(2):517–521

Bosmans K, Decancq K, Ooghe E (2017) Who’s afraid of aggregating money metrics? mimeo

Boyce CJ (2010) Understanding fixed effects in human wellbeing. J Econ Psychol 31:1–16

Capéau B, Decoster A, Dekkers G (2016) Estimating and simulating with a random utility random opportunity model of job choice presentation and application to Belgium. Int J Microsimulat 9(2):144–191

Carpantier JF, Sapata C (2016) Empirical welfare analysis: when preferences matter. Soc Choice Welf Econ 46(3):521–542

Chetty R (2012) Bounds on elasticities with optimization frictions: a synthesis of microand macro evidence on labor supply. Econometrica 80:969–1018

Chiappori P-A, Donni O (2011) Non-unitary models of household behavior: a survey of the literature. In: Molina A (ed) Household economic behaviors. Springer, Berlin

Clark A, Oswald A (1994) Unhappiness and unemployment. Econ J 104(424):648–659

Clark AE, Frijters P, Shields M (2008) Relative income, happiness and utility: an explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. J Econ Lit 46(1):95–144

Clark A, Senik C, Yamada K (2015) When experienced and decision utility concur: the case of income comparisons, IZA DP No. 9189

Dagsvik JK, Strøm S (2006) Sectoral labour supply, choice restrictions and functional form. J Appl Econ 21(6):803–826

Decancq K, Schokkaert E (2013) Beyond GDP: measuring social progress in Europe. Mimeo, KU Leuven

Decancq K, Fleurbaey M, Schokkaert E (2014) Happiness, equivalent incomes, and respect for individual preferences. Economica

Decancq K, Fleurbaey M, Schokkaert E (2015) Inequality, income, and well-being. In: Atkinson AB, Bourguignon F (eds) Handbook on income distribution, vol 2A. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 67–140

Decancq K, Neumann D (2015) Does the choice of well-being measure matter empirically? In: Adler M, Fleurbaey M (eds) Oxford handbook of well-being and public policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Decoster A, Haan P (2015) Empirical welfare analysis with preference heterogeneity. Int Tax Public Financ 22(2):224–251

Ferrer-i Carbonell A, van Praag BMS, Theodossiou I (2010) Vignette equivalence and response consistency: the case of job satisfaction, IZA DP 6174

Fleurbaey M (2006) Social welfare, priority to the worst-off and the dimensions of individual well-being. In: Farina F, Savaglio E (eds) Inequality and economic integration. Routledge, London

Fleurbaey M (2008) Fairness, responsibility and welfare. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fleurbaey M (2009) Beyond GDP: the quest for a measure of social welfare. J Econ Lit 47:1029–1075

Fleurbaey M, Maniquet F (2006) Fair income tax. Rev Econ Stud 73(1):55–83

Fleurbaey M, Maniquet F (2007) Help the low skilled or let the hardworking thrive? A study of fairness in optimal income taxation. J Public Econ Theory 9:467–500

Fleurbaey M, Maniquet F (2011) A theory of fairness and social welfare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fleurbaey M, Maniquet F (2014) Optimal taxation theory and principles of fairness. Core Discussion Paper

Fleurbaey M, Blanchet D (2013) Beyond GDP, measuring welfare and assessing sustainability. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fleurbaey M, Schwandt H (2015) Do people seek to maximize their subjective well-being? IZA DP No. 9450

Fleurbaey M, Schokkaert E (2013) Behavioral welfare economics and redistribution. Am Econ J Microecon 5(3):180–205 201

Frijters P (2000) Do individuals try to maximise satisfaction with life as a whole. J Econ Psychol 21:281–304

Frijters P, Greenwell H, Shields MA, Haisken-DeNew JP (2009) How rational were expectations in East Germany after the falling of the wall? Can J Econ 42(4):1326–1346

Glaeser EL, Gottlieb JD, Ziv O (2016) Unhappy cities. J Labor Econ 34(S2):S129–S182

Haan P, Uhlendorff A (2013) Intertemporal labor supply and involuntary unemployment. Empir Econ 44(2):661–683

Hamermesh DS, Slemrod JB (2008) The economics of workaholism: we should not have worked on this paper. BE J Econ Anal Policy 8(1)

Hoynes HW (1996) Welfare transfers in two-parent families: labor supply and welfare participation under AFDC-UP. Econometrica 64(29):295–332

Jacquet L, Van de Gaer D (2011) A comparison of optimal tax policies when compensation or responsibility matter. J Public Econ 95(11–12):1248–1262

Jara XH, Schokkaert E (2017) Putting measures of individual well-being to use for ex-ante policy evaluation. J Econ Inequal 15(4):421–440

Kahneman D, Krueger A, Schkade DA, Schwarz N, Stone A (2006) Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science 312:1908–1910

Kitagawa T, Nybom M, Stuhler J (2018) Measurement error and rank correlations. Cemmap Working Paper CWP28/18

Lise J, Seitz S (2011) Consumption inequality and intra-household allocations. Rev Econ Stud 78(1):328–355

Loewenstein G, O’Donoghue T, Rabin M (2003) Projection bias in predicting future utility. Quart J Econ 118:1209–1248

Ng Y-K (1997) A case for happiness, cardinalism, and interpersonal comparison. Econ J 107(445):1848–1858

Odermatt R, Stutzer A (2015) (Mis-)predicted subjective well-being following life events. IZA DP No. 9252

Ooghe E, Peichl A (2011) Fair and efficient taxation under partial control: theory and evidence. Econ J

Pazner E, Schmeidler D (1978) Egalitarian equivalent allocations: a new concept of economic equity. Q J Econ 92:671–686

Peichl A, Siegloch S (2012) Accounting for labor demand effects in structural labor supply models. Lab Econ 19(1):129–138

Pencavel J (1977) Constant-utility index numbers of real wages. Am Econ Rev 67(2):91–100

Perez-Truglia R (2015) A Samuelsonian validation test for happiness data. J Econ Psychol 49:74–83

Petrongolo B (2004) Gender segregation in employment contracts. J Eur Econ Assoc 2(2/3, P&P):331–345

Ravallion M, Lokshin M (2001) Identifying welfare effect from subjective questions. Economica 68:335–357

Schokkaert E, Van de Gaer D, Vandenbroucke F, Luttens RI (2004) Responsibility sensitive egalitarianism and optimal linear income taxation. Math Soc Sci 48:151–182

Schokkaert E, Van Ootegem L, Verhofstadt E (2011) Preferences and subjectivejob satisfaction: measuring wellbeing on the job for policy evaluation. CESifo Econ Stud 57:683–714

Sen A (1985) Commodities and capabilities. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Senik C (2005) Income distribution and well-being: what can we learn from subjective data? J Econ Surv 19:43–63

Stiglitz J, Sen A, Fitoussi J-P (2009) Report by the Commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress, technical report

Stutzer A, Frey BS (2008) Stress that doesn’t pay: the commuting paradox. Scand J Econ 110(2):339–366

Thomson W (1994) Notions of equal, or equivalent, opportunities. Soc Choice Welf 11:137–156

Thomson W (2011) Fair allocation rules. In: Arrow KJ, Sen AK, Suzumura K (eds) Handbook of social choice andwelfare, vol 2. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Trannoy A (2016) Equality of opportunity: a progress report. ECINEQ working paper

van Praag BMS, Frijters P, Ferrer-i-Carbonell A (2003) The anatomy of subjective well-being. J Econ Behav Organ 51:29–49

van Soest A (1995) Structural models of family labor supply: a discrete choice approach. J Hum Resour 30(1):63–88

van Soest A, Das M, Gong X (2002) A structural labor supply model with non-parametric preferences. J Econ 107(1–2):345–374

Viitanen T (2005) Cost of childcare and female employment in the UK. Labour 19(Special Issue):149–179

Wichert L, Pohlmeier W (2010) Female labor force participation and the big five. ZEW discussion paper 10-003

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two referees and to participants to seminars (LSE, ISER, AMSE) and conference (Royal Economic Society, HDCA, Warsaw International Economic Meeting) for useful suggestions. We are indebted to Jan Stuhler for his help on the application of a new method to correct rank correlation from the bias associated with measurement errors, as developed by him and his coauthors (Kitagawa et al. 2018). The work by H. Xavier Jara was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the Research Centre on Micro-Social Change (MiSoC) at the University of Essex, grant number ES/L009153/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

A Appendix

1.1 A.1 Models specification

Specification of the utility functions Both experienced and decision utilities are specified according to the box-cox form:

Used in recent welfare analyses (Decoster and Haan 2015; Bargain et al. 2013), box-cox utility allows easily checking that preferences are well-behaved, which facilitates the derivation of ordinal preferences (i.e., indifference curves) and the calculation of welfare metrics. Monotonicity and concavity conditions on consumption and leisure are satisfied if, respectively, \(\beta \)’s are positive and \(\lambda \)’s are in a range between 0 and 1. We check ex post that both conditions are fulfilled empirically for all our observations. More flexible forms could be used but tangency conditions are necessary for calculating welfare metrics.Footnote 31

Preference heterogeneity across individuals is introduced as follows. Parameters on leisure vary linearly with taste shifters \(x_{it}\) and a normally distributed random term \(\phi _{i}\):

Vector \(x_{it}\) includes the following binary characteristics: male, age above 40, higher education, presence of children aged 0 to 2, living in London, non-white ethnic origin, migrant, above-average conscientiousness and above-average neuroticism. Unobserved preferences \(\phi _{i}\) are dealt with using simulated maximum likelihood.

Budget constraints In both approaches, disposable income is computed according to the budget constraint \(y_{it}=\psi _{t}(w_{it}h_{it},\mu _{it},\zeta _{it})\). Function \(\psi _{t}\) aggregates gross earnings \(w_{it}h_{it}\) and unearned income \(\mu _{it}\) into net income \(y_{it}\), adding taxes and withdrawing benefits that depend on these income levels (benefit means-tested, tax brackets, etc.) and on individual characteristics \(\zeta _{it}\) (tax credits or benefits being a function of family composition, for instance). It is approximated by numerical simulations using the tax-benefit rules of each period \(t=1,\ldots ,T\). In the same way, we also predict \((y_{ijt},\tau -h_{ijt})\) pairs for the \(j=1,\ldots J\) potential choices used in the labor supply model. To do so, we first estimate an Heckman-corrected wage equation (instrument is non-labor income and the presence of children aged 0–2) in order to predict wage rates \(w_{it}\) (wages are unobserved for non-workers). Then we numerically compute disposable income \(y_{ijt}=\psi _{t}(w_{it}h_{ijt},\mu _{it},\zeta _{it})\) for the J discrete labor supply values of \(h_{ijt}\) (see Bargain et al. 2014).

Identification and limitations The econometric identification of ordinal preferences requires some discussions (see also Akay et al. 2015). For labor supply models, a well-known difficulty pertains to the role of omitted preference shifters that may affect both wage rates and work preferences. For instance, hard-working types may work a lot also because they tend to have higher wage rates, i.e. an underestimation of preferences for leisure. For the SWB model, a similar type of bias may exist. For instance, actual heterogeneity in work preferences may be correlated with other unobserved determinants of well-being. If hard workers are more likely to experience positive shocks to SWB, then the bias goes in the same direction as for labor supply, i.e. work aversion is underestimated. However, the bias could go the other way. We suggest three strategies to reduce these concerns. First, we account for individual heterogeneity \(x_{it}\)–notably relevant personality traits, i.e. conscientiousness and neuroticism—in work preferences and, for the SWB equation, in the separately additive term \(z_{it}\). Second, we account for random preference-for-leisure parameters (note, however, that \(\phi _{i}\) is normally distributed and, hence, cannot capture the true distribution of omitted variables). Finally, and most importantly, we use spatial and temporal variation in factors that affect the net wages. As used in the labor supply literature, it corresponds to spatial variation in tax-benefit rules (Hoynes 1996) and time variation in these rules over 1996–2005 (i.e., tax-benefit reforms, as in Blundell et al. 1998). The period covered in our data includes quite much variation in tax-benefit rules to improve identification (see a detailed account in Akay et al. 2015). These approaches are the best we can do in the present setting. Nonetheless, one can never exclude that remaining biases cause some of the observed differences between preferences derived from both methods.

1.2 A.2 Models estimation results

See Table 3.

B Online appendix

1.1 B.1 Indifference curves by broad groups

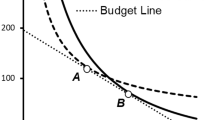

We derive indifference curves in the income-leisure space for every individual in our sample. For the whole population (graph A) or within each group (graphs B–H), we average individual indifference curves through a common point set at 40 h of leisure and \(\overline{y}(40)\) (the sample mean net income at this leisure level) (Fig. 8).

Indifference curves with revealed vs. subjective preferences. Note: solid (dash) lines indicated indifference curves for revealed (subjective) preferences. Indifference curve representations on these graphs are obtained using estimated parameters of the income-leisure utility functions, overall or for particular groups (e.g. women), and averaging individual indifference curves drawn through a common point, defined as \((\overline{y}(40),40)\) On the graphs, weekly leisure points range from 20 to 80 h, corresponding to weekly work hours from 60 (overtime) to 0 (inactivity)

1.2 B.2 Reranking by broad groups

Welfare rank correlation (rent metric) by groups, using group-specific ranks. Note: for the Rent metric, the graph compares welfare ranks with revealed versus subjective preferences, i.e. income-leisure ordinal preferences from actual choices versus from SWB experienced at these choices. Observations are grouped by demographic type, using group-specific ranks

Welfare rank correlation (rent metric) by groups, using overall ranks. Note: for the Rent metric, the graph compares welfare ranks with revealed versus subjective preferences, i.e. income-leisure ordinal preferences from actual choices versus from SWB experienced at these choices. Observations are grouped by demographic type, using overall ranks

1.3 B.3 Results for the wage metric

Welfare rank correlation (wage metric): whole sample. Note: for the Wage metrics, these graphs compare the welfare ranks obtained with revealed vs. subjective preferences, i.e. income-leisure ordinal preferences from actual choices vs. from the SWB experienced at these choices. Preferences are modelled using box-cox utility functions with preference heterogeneity (male, age, education, presence of young children, London, non-white, migrant, conscientious, neurotic)

Welfare rank correlation (wage metric) by gender, using overall ranks. Note: for the Wage metric, the graph compares welfare ranks with revealed versus subjective preferences, i.e. income-leisure ordinal preferences from actual choices versus from SWB experienced at these choices. Observations are grouped by gender type, using overall ranks

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akay, A., Bargain, O. & Jara, H.X. ‘Fair’ welfare comparisons with heterogeneous tastes: subjective versus revealed preferences. Soc Choice Welf 55, 51–84 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-019-01231-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-019-01231-4