Abstract

Objectives

Supplemental MRI screening improves early breast cancer detection and reduces interval cancers in women with extremely dense breasts in a cost-effective way. Recently, the European Society of Breast Imaging recommended offering MRI screening to women with extremely dense breasts, but the debate on whether to implement it in breast cancer screening programs is ongoing. Insight into the participant experience and willingness to re-attend is important for this discussion.

Methods

We calculated the re-attendance rates of the second and third MRI screening rounds of the DENSE trial. Moreover, we calculated age-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) to study the association between characteristics and re-attendance. Women who discontinued MRI screening were asked to provide one or more reasons for this.

Results

The re-attendance rates were 81.3% (3458/4252) and 85.2% (2693/3160) in the second and third MRI screening round, respectively. A high age (> 65 years), a very low BMI, lower education, not being employed, smoking, and no alcohol consumption were correlated with lower re-attendance rates. Moderate or high levels of pain, discomfort, or anxiety experienced during the previous MRI screening round were correlated with lower re-attendance rates. Finally, a plurality of women mentioned an examination-related inconvenience as a reason to discontinue screening (39.1% and 34.8% in the second and third screening round, respectively).

Conclusions

The willingness of women with dense breasts to re-attend an ongoing MRI screening study is high. However, emphasis should be placed on improving the MRI experience to increase the re-attendance rate if widespread supplemental MRI screening is implemented.

Clinical relevance statement

For many women, MRI is an acceptable screening method, as re-attendance rates were high — even for screening in a clinical trial setting. To further enhance the (re-)attendance rate, one possible approach could be improving the overall MRI experience.

Key Points

• The willingness to re-attend in an ongoing MRI screening study is high.

• Pain, discomfort, and anxiety in the previous MRI screening round were related to lower re-attendance rates.

• Emphasis should be placed on improving MRI experience to increase the re-attendance rate in supplemental MRI screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Women with dense breasts have an increased risk of breast cancer compared to women who have more fatty breasts [1]. Moreover, the sensitivity of mammography is lower among women with dense breasts due to the masking effect of the dense breast tissue [1,2,3]. As a result, more tumours are missed in women with dense breasts at mammographic screening, resulting in an increased interval cancer rate; interval cancers are those detected in between screening rounds. Interval cancers are generally more aggressive as they are typically larger, grow faster, and spread more quickly than cancers detected at screening, and they are often found at a later or symptomatic stage [4, 5]. Therefore, the Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening (DENSE) trial investigated the effectiveness of supplemental magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on reducing interval cancer rates in women with dense breasts (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT01315015) [6]. The results of the first screening round of the DENSE trial showed that adding MRI screening to biennial mammography resulted in significantly fewer interval cancers than if mammography was used alone [7].

In a previous study, we investigated the attendance rate in the first MRI round and the reasons for non-participation [8]. Fifty-nine percent of the women invited for supplemental MRI screening participated in the first round. Most mentioned reasons for non-participation were MRI-related inconveniences, such as claustrophobia, and/or self-reported contraindications, personal reasons, or anxiety regarding the result of supplemental screening. For a breast cancer screening program to be effective, it is important that women attend on a regular basis [9]. To inform the discussion about implementing MRI screening for women with extremely dense breasts, it is important to know whether they re-attend after one or more MRI screening rounds, and if not, why. Here, we present the re-attendance rates in subsequent screening rounds of the DENSE trial and reasons given by participants to discontinue screening during subsequent screening rounds. Knowledge of these MRI re-attendance rates and reasons for discontinuation in subsequent screening rounds could facilitate efforts to improve MRI screening uptake and experience.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The Dutch Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport, who was advised by the Health Council of the Netherlands (2011/2019 WBO, The Hague, The Netherlands), approved the DENSE trial on November 11, 2011. All participants provided written informed consent.

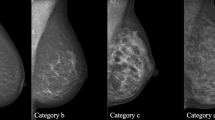

The DENSE trial is embedded within the Dutch population-based digital mammography screening program (age 50–75) and consists of three biennial screening rounds. The study design and outcomes of the first and second rounds have been described previously [6, 7, 10]. Women were eligible for the DENSE trial if they had extremely dense breasts (grade 4 or d) as measured with Volpara version 1.5 (Volpara Health Technologies) and if they had a negative mammography result (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System [BI-RADS] category 1 or 2).

All MRI examinations were performed on 3.0-T MRI systems with the macrocyclic gadolinium-based contrast agent gadobutrol (0.1 mmol/kg body weight) (Gadovist; Bayer AG). Details on the full screening MRI protocol have been described previously [6].

Workflow screening rounds DENSE trial

Between December 2011 and January 2016, 4783 women were randomised to the intervention arm and participated in the first screening round of the DENSE trial. Women with a breast cancer diagnosis, an age outside the age range of the screening program (> 75 years) or women who passed away or moved abroad during or after the previous screening round, were not invited for subsequent screening rounds. All other women were invited again for mammographic screening 2 years after the previous (first or second) MRI round; women who participated in this mammographic screening and again had a negative (‘normal’) mammography result were invited for the next MRI round. Women who were referred for diagnostic work-up as a result of the mammographic screening were excluded from the corresponding MRI round (not invited).

Calculation of the re-attendance rate

We assessed the re-attendance rate as follows: the numerator consisted of all women who participated in the second (or third) MRI round of the DENSE trial. The denominator consisted of all women who were invited for the second (or third) MRI round.

As a sensitivity analysis, we used a different denominator consisting of all women who were invited for the second (or third) MRI round but also the women who had actively unsubscribed for further participation in the DENSE trial before they were invited, and women who had declined their invitation for mammography. We performed this sensitivity analyses because a woman’s decision to decline the mammography invitation could have been influenced by their previous MRI experience. To further elaborate this hypothesis, we analysed the previous MRI experiences in attendance subgroups (participants, non-participants of MRI, non-participants of mammography and MRI). Information on reasons for declining mammography screening invitations was not available.

Participant characteristics related to re-attendance

We described participant characteristics of women who re-attended and those who did not.

Participants completed a self-report questionnaire about demographic, reproductive and lifestyle factors, and their (family) medical history. We collected information about postal codes from the data available from the Dutch mammography program to classify socioeconomic status (SES).

Factors related to MRI screening experience

MRI-related (serious) adverse events ((S)AEs) were reported directly after the MRI and were self-reported by women within 30 days after the MRI examination when applicable. An MRI screen-specific items questionnaire was administered 2 days after each MRI examination to assess pain, discomfort, and anxiety experienced during the MRI examination [11]. A false-positive finding was defined as a positive MRI result (BI-RADS 3, 4, or 5) without a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Collection of self-reported reasons for discontinuation

Women were able to discontinue participation in the DENSE trial at any time. In this case, they were asked to provide one or more reasons for discontinuation. Subsequently, all reasons were registered, and we classified them into the following categories: MRI-related inconveniences and/or self-reported contraindications, anxiety regarding the outcome, personal reasons, practical reasons, burden too high, or reasons related to surveillance (e.g. already under active surveillance) [8]. We classified concerns around gadolinium retention in the brain as a reason for discontinuation under MRI-related inconveniences and/or self-reported contraindications [12, 13]. From March 2020 onwards, women were also able to provide ‘not wanting to go to the hospital due to the COVID-19 pandemic’ as a reason, which we categorised as a practical reason. When women declined the invitation due to a later acquired contraindication, we classified this as an MRI-related inconvenience and/or self-reported contraindication. Reasons were classified by two authors, and in case of disagreement, consensus was reached upon assessment of a third author.

Data analyses

The outcome for the analyses was screening re-attendance as defined previously. We reported characteristics and previous MRI experience as proportions (percentage) of women in the category that re-attended. We reported the means with standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables.

We examined differences between participants and non-participants using Pearson’s chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables. We calculated p-values for trend. Additionally, we determined whether factors were associated with re-attendance, by fitting logistic regression models adjusted for age to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). An OR above 1 indicates that women are more likely to drop-out, thus less likely to re-attend, in the next MRI screening round.

We summarised reasons to discontinue screening using descriptive statistics for all women who actively unsubscribed for further participation in the trial after the first or second round or who declined the invitation for the subsequent MRI screening round.

Calculations were based on the data collected until 2020–10-06.

We performed all analyses using RStudio software (RStudio, version 1.3.1093).

Results

Re-attendance rates

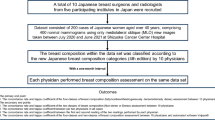

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of participation in the first, second, and third rounds of the DENSE trial. In the first MRI round, 4783 women participated. Between the first round and before the invitations for the second MRI round, women were excluded for various reasons (e.g. moved abroad, passed away, outside age range). A total of 3458 women participated in the second MRI screening round. The denominator of the re-attendance rate was 4252, which was the number of women who were invited for the second MRI screening round. This resulted in a re-attendance rate in the second DENSE MRI round of 81.3% (3458/4252).

Between the second and third MRI screening rounds, women were excluded for various reasons (e.g. moved abroad, outside age range). A total of 2693 women participated in the third MRI screening round. The denominator of the re-attendance rate was 3160, which was the number of women who were invited for the third MRI screening round. This resulted in a re-attendance rate in the third MRI round of 85.2% (2693/3160).

As a sensitivity analysis, we calculated the re-attendance rate with the same numerator but a different denominator (including the women who declined the mammography screening invitation and the women who actively unsubscribed for further participation in MRI screening). This resulted in a re-attendance rate in the second MRI round of 76.1% (3458 / (4252 + 261 + 29 = 4542)) and a re-attendance rate in the third MRI round of 81.1% (2693 / (3160 + 132 + 29 = 3321)). Related to this analysis, we created subgroups to check the hypothesis that a previous MRI experience could influence the decision to decline the next mammography invitation (see Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Of the women who experienced very much anxiety during the first MRI round, 29% (5/17) declined the next mammography invitation, compared to 26% (153/586) of the women who experienced no anxiety during the previous MRI round (p = 0.04). Of the women who had a false-positive result in the first MRI round, 43% (46/108) declined the next mammography invitation, compared to 22% (215/976) of the women who experienced no anxiety during the previous MRI round (p < 0.01). These women, who did not attend mammographic screening, were not invited for MRI screening. Similar results were observed for the third round, although less profound (Supplemental Table 2).

Study population characteristics

After adjusting for age, nine characteristics were statistically significantly associated with re-attendance in the second screening round (Table 1). Older women (70–74 years) were more likely to drop-out than younger women (50–54 years) (OR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.28–3.31). Women with a BMI between 18.5–24.9 and 25–30 (kg/m3) were less likely to drop-out than women with a BMI below 18.5 (OR, 0.57, 95% CI, 0.41–0.80; OR, 0.50, 95% CI, 0.33–0.76, respectively.). Women who had a higher education were less likely to drop-out than women who had a lower education (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30–0.94). Women who were currently employed were less likely to drop-out than women who were not employed (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37–0.67). Women who currently smoked were more likely to drop-out than women who never smoked (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.26–1.99). Women with a moderate alcohol consumption were less likely to drop-out than women with no alcohol consumption (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.47–0.75). Women were more likely to drop-out with increasing pain during the previous MRI round (ORlittle, 1.95; ORmoderate, 2.64; ORvery much, 8.04). Women were more likely to drop-out with increasing discomfort during the previous MRI round (ORlittle, 1.49; ORmoderate, 2.63; ORvery much, 4.73). Women were more likely to drop-out with increasing anxiety during the previous MRI round (ORlittle, 1.89; ORmoderate, 4.72; ORvery much, 2.97). The results of the third screening round were comparable to that of the second screening round; however, the associations between age or education and re-attendance were less profound.

Reasons for discontinuation

Table 2 summarises the reasons for discontinuation for the women who either actively unsubscribed for further participation or who declined the invitation (n = 595 in the second round and n = 496 in the third round). In the second round, women who discontinued provided a total of 952 reasons.

Approximately 39.1% (372/952) of all provided reasons were MRI-related inconveniences and/or self-reported contraindications. MRI-related inconveniences can be subdivided into MRI-specific reasons (25.4%), such as claustrophobia and too much noise at the MRI examination, and contrast agent–related reasons (13.7%), such as refusing gadolinium. Moreover, 8.3% of all provided reasons to discontinue were related to anxiety caused by the MRI examination, 23.1% to practical reasons, and 16.6% to personal reasons. In the third screening round, women who discontinued provided a total of 566 reasons. Approximately 34.8% of all provided reasons were MRI-related inconveniences and/or self-reported contraindications. MRI-related inconveniences can be subdivided into MRI-specific reasons (14.3%), such as claustrophobia and too much noise at the MRI examination, and contrast agent–related reasons (20.5%), such as refusing gadolinium. Moreover, 6.7% of all provided reasons to discontinue were related to anxiety caused by the MRI examination, 24.4% to practical reasons, and 18.9% to personal reasons. The reasons to discontinue in the second or third rounds were similar.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the re-attendance in subsequent screening rounds of the DENSE trial. Among those invited, the re-attendance rates were high: 81.3% (3458/4252) in the second and 85.2% (2693/3160) in the third round of the DENSE trial. Women who did not re-participate, in both screening rounds: more often had a very low BMI (< 18.5); were less often employed; were more often current smokers; were less often moderate alcohol consumers; and more often perceived pain, discomfort, or anxiety during the previous MRI round. MRI-related inconveniences, specifically reasons such as claustrophobia and too much noise, were mentioned most frequently in both screening rounds as a reason not to continue screening.

We do not have much literature to compare our study with, as there are limited screening MRI studies with multiple screening rounds. Multiple studies address adherence in mammographic screening programs. Our results are in line with the results of a meta-analysis conducted by Damiani et al, who concluded that women with a higher educational status were more likely to adhere to mammographic breast cancer screening than women with a lower educational status [14].

Furthermore, we studied the reasons for discontinuing screening; MRI-specific inconveniences such as claustrophobia and too much noise at the MRI examination were most frequently mentioned reasons to discontinue in our study. This indicates that a prior unfavourable experience with breast MRI could have a negative impact on women’s willingness to re-attend in another screening round. In a previous paper on initial reasons for non-participation in the DENSE trial, MRI-specific inconveniences, with claustrophobia being the most frequently cited, were also most often given as reason to not participate [8]. A recent study conducted by Berg et al investigated patient preferences for contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) versus MRI as supplemental screening options [15]. One frequently mentioned reason for preferring CEM over MRI was also claustrophobia. However, it should be noted that the effectiveness of CEM in a population-based screening setting merits further validation. A potential approach to reduce the concern about claustrophobia would be to offer an abbreviated form of MRI, in which women spend less time inside the MRI machine. Additionally, it is important to give the opportunity to women to communicate any concerns or potential discomforts with the medical staff before the MRI examination. They can provide guidance on how to manage or alleviate some of these discomforts. Finally, among the MRI-related inconveniences, contrast agent–related reasons were given, which likely would affect not only MRI, but also other contrast-enhanced techniques, including CEM. An alternative study that does not require contrast is ultrasound. However, due to limited incremental cancer detection yield of ultrasound, the European Society of Breast Screening (EUSOBI) recommends this technique only in situations where MRI screening is unavailable [16].

We found no difference in re-attendance in both MRI screening rounds between women who had a false-positive result in the previous MRI screening round and women who had not. However, in the sensitivity analyses, we found that women who had a false-positive result in the previous MRI screening round less often participated in the subsequent mammographic screening round. Women who did not attend the mammographic screening did not receive an invitation for the next MRI screening round. This finding is in line with most previous studies that investigated the effect of a false-positive result on re-attendance in mammographic screening; women with a false-positive mammogram were less likely to re-attend and were more likely to delay their subsequent screening [17, 18]. However, some studies have found the opposite effect of a false-positive result [19]. In a previous paper, we showed that the false-positive rate decreased from 79.8/1000 screenings in the first MRI round to 26.3/1000 screenings in the second MRI round [10]. It is expected that the false-positive rate will decrease further during subsequent screening rounds. Thus, any adverse effects on attendance due to false positives are expected to decrease with incidence screening.

A major strength of this study is the large sample size. Moreover, the sample population is a good representation of the domain under study due to the multicentre design of the trial and its embedment in the national breast cancer screening program. A limitation, however, is that we do not have any direct information about ethnicity, since it is illegal to register ethnicity in The Netherlands. This makes it more difficult to extrapolate these results to other populations. Another limitation of the study is that we had no information on reasons for drop-out for women who did not return to the mammographic screening program. An unfavourable MRI screening experience in the preceding screening round might be a reason not to return to the mammographic breast cancer screening program.

Recently, the EUSOBI recommended MRI as a supplemental screening technique for women with extremely dense breasts, but the debate on its implementation in breast screening programs is ongoing [19]. From our study, we conclude that for many women MRI is an acceptable screening method, as re-attendance rates were high — even for screening in a clinical trial setting. To further increase (re-)attendance, one option could be to improve MRI experience. This could be accomplished by implementing the use of wide-bore MRI scanners, which might decrease feelings of claustrophobia [20, 21], or implementing abbreviated forms of MRI which reduce acquisition time and noise levels. Furthermore, the occurrence of false-positive MRI results could potentially be reduced in the future, by using prediction rules for false-positive outcomes based on patient and imaging characteristics and/or introducing machine learning methods that could better distinguish malignant from benign breast cancer lesions on an MRI scan [22]. Finally, awareness and better education about extremely dense breasts and supplemental screening might increase (re-)attendance.

Abbreviations

- CEM:

-

Contrast-enhanced mammography

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DENSE trial:

-

Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening

- EUSOBI:

-

European Society of Breast Imaging

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SAE:

-

Serious adverse events

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

References

Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ et al (2007) Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 356(3):227–236

Wanders JO, Holland K, Veldhuis WB et al (2017) Volumetric breast density affects performance of digital screening mammography. Breast Cancer Res Treat 162:95–103

Mandelson MT, Oestreicher N, Porter PL et al (2000) Breast density as a predictor of mammographic detection: comparison of interval-and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 92(13):1081–1087

Pilewskie M, Zabor EC, Gilbert E et al (2019) Differences between screen-detected and interval breast cancers among BRCA mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 175:141–148

Burrell HC, Sibbering DM, Wilson AR et al (1996) Screening interval breast cancers: mammographic features and prognosis factors. Radiology 199(3):811–817

Emaus MJ, Bakker MF, Peeters PH et al (2015) MR imaging as an additional screening modality for the detection of breast cancer in women aged 50–75 years with extremely dense breasts: the DENSE trial study design. Radiology 277(2):527–537

Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM et al (2019) Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med 381(22):2091–2102

De Lange SV, Bakker MF, Monninkhof EM et al (2018) Reasons for (non) participation in supplemental population-based MRI breast screening for women with extremely dense breasts. Clin Radiol 73(8):759-e1

Drossaert CH, Boer H, Seydel ER (2005) Women’s opinions about attending for breast cancer screening: stability of cognitive determinants during three rounds of screening. Br J Health Psychol 10(1):133–149

Veenhuizen SG, de Lange SV, Bakker MF et al (2021) Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology 299(2):278–286

Rijnsburger AJ, Essink-Bot ML, van Dooren S et al (2004) Impact of screening for breast cancer in high-risk women on health-related quality of life. Br J Cancer 91(1):69–76

McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF et al (2015) Intracranial gadolinium deposition after contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 2753:772–782

Kanda T, Fukusato T, Matsuda M et al (2015) Gadolinium-based contrast agent accumulates in the brain even in subjects without severe renal dysfunction: evaluation of autopsy brain specimens with inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy. Radiology 2761:228–232

Damiani G, Basso D, Acampora A et al (2015) The impact of level of education on adherence to breast and cervical cancer screening: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 81:281–289

Berg WA, Bandos AI, Sava MG et al (2023) Analytic hierarchy process analysis of patient preferences for contrast-enhanced mammography versus MRI as supplemental screening options for breast cancer. J Am Coll Radiol 20(8):758–768

Mann RM, Athanasiou A, Baltzer PA et al (2022) Breast cancer screening in women with extremely dense breasts recommendations of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI). Eur Radiol 32(6):4036–4045

Setz-Pels W, Duijm LEM, Coebergh JW, Rutten M, Nederend J, Voogd AC (2013) Re-attendance after false-positive screening mammography: a population-based study in the Netherlands. Br J Cancer 109(8):2044–2050

Dabbous FM, Dolecek TA, Berbaum ML et al (2017) Impact of a false-positive screening mammogram on subsequent screening behavior and stage at breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 26(3):397–403

Pisano ED, Earp JA, Gallant TL (1998) Screening mammography behavior after a false positive mammogram. Cancer Detect Prev 22(2):161–167

Bangard C, Paszek J, Berg F et al (2007) MR imaging of claustrophobic patients in an open 1.0 T scanner: motion artifacts and patient acceptability compared with closed bore magnets. Eur J Radiol 64(1):152–157

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Murphy F (2015) Claustrophobia in magnetic resonance imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiography 21(2):e59–e63

Reig B, Heacock L, Geras KJ, Moy L (2020) Machine learning in breast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 52(4):998–1018

Alcoholgebruik onder volwassenen, Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (2022) Available via https://www.rivm.nl/leefstijlmonitor/alcoholgebruik-onder-volwassenen. Accessed 2 Feb 2023

Wareham NJ, Jakes RW, Rennie KL et al (2003) Validity and repeatability of a simple index derived from the short physical activity questionnaire used in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Public Health Nutr 6(4):407–413

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the trial participants for their contributions. The authors thank the regional screening organisations, Volpara Solutions, the Dutch Expert Centre for Screening, and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment for their advice and in-kind contributions for organizing the breast density assessments and the invitation of potential participants. The DENSE trial is financially supported by the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMC Utrecht, project number: UMCU DENSE), the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, project numbers: ZONMW-200320002-UMCU and ZonMW Preventie 50-53125-98-014), the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding, project numbers: DCS-UU-2009-4348, UU-2014-6859, and UU-2014-7151), the Dutch Pink Ribbon/a Sister’s hope (project number: Pink Ribbon-10074), Bayer AG Pharmaceuticals, Radiology (project number: BSP-DENSE), and Stichting Kankerpreventie Midden-West. For research purposes, Volpara Health Technologies (Wellington, New Zealand) has provided Volpara Imaging Software 1.5 for installation on servers in the screening units of the Dutch screening program. The authors thank the registration team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) for the collection of data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

DENSE Trial Study Group: C H van Gils, M F Bakker, S E L van Grinsven, S V de Lange, S G A Veenhuizen, W B Veldhuis, R M Pijnappel, M J Emaus, E M Monninkhof, M A Fernandez-Gallardo, M A A J van den Bosch, P J van Diest, R M Mann, R Mus, M Imhof-Tas, N Karssemeijer, C E Loo, P K de Koekkoek-Doll, H A O Winter-Warnars, R H C Bisschops, M C J M Kock, R K Storm, P H M van der Valk, M B I Lobbes, S Gommers, M B I Lobbes, M D F de Jong, M J C M Rutten, K M Duvivier, P de Graaf, J Veltman, R L J H Bourez, H J de Koning.

Funding

This study has received funding by UMC Utrecht, ZonMW, KWF Kankerbestrijding. Bayer AG Pharmaceuticals, Radiology, Stichting Kankerpreventie Midden-West.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Carla van Gils.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare relationships with the following companies: Siemens Healthineers (R.M.), Koning (R.M.), PA imaging (R.M.), Screenpoint medical (R.M., N.K.), BD (R.M.), Micrima (R.M.), Volpara Health Care ltd (R.M.), QView Medical Inc (N.K.), Samantree (P.v.D), Sectra (P.v.D.), Visiopharm (P.v.D.), Paige (P.v.D). R.M. is a member of the European Radiology Advisory Editorial Board (European Society of Breast Imaging), and they have not taken part in the review or selection process of this article. The remaining authors declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study.

Ethical approval

Institutional review board approval was obtained.

Study subjects or cohorts overlap

The trial participants and other trial outcomes have been described earlier:

1. Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM et al (2019) Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. New England Journal of Medicine 381.22:2091–2102

2. De Lange SV, Bakker MF, Monninkhof EM et al (2018) Reasons for (non) participation in supplemental population-based MRI breast screening for women with extremely dense breasts. Clinical Radiology 73.8:759-e1.

3. Veenhuizen SG, de Lange SV, Bakker MF et al (2021) Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology 299.2:278–286.

The outcomes related to participation in the second and third screening round of DENSE have not been published before.

Methodology

• prospective

• randomised controlled trial

• multicentre study

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Stefanie G. A. Veenhuizen and Sophie E. L. van Grinsven are co-first authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Veenhuizen, S.G.A., van Grinsven, S.E.L., Laseur, I.L. et al. Re-attendance in supplemental breast MRI screening rounds of the DENSE trial for women with extremely dense breasts. Eur Radiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-024-10685-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-024-10685-9