Abstract

Physical activity (PA) is recommended as a key component in the management of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The objective of this study was to examine the feasibility of a physiotherapist led, behaviour change (BC) theory-informed, intervention to promote PA in people with RA who have low levels of current PA. A feasibility randomised trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03644160) of people with RA over 18 years recruited from outpatient rheumatology clinics and classified as insufficiently physically active using the Godin−Shephard Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. Participants were randomised to intervention group (4 BC physiotherapy sessions in 8 weeks) delivered in person/virtually or control group (PA information leaflet only). Feasibility targets (eligibility, recruitment, and refusal), protocol adherence and acceptability were measured. Health care professionals (HCPs) involved in the study and patients in the intervention and control arms were interviewed to determine acceptability. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data with SPSS (v27) with interviews analysed using content analysis using NVivo (v14). Three hundred and twenty participants were identified as potentially eligible, with n = 183 (57%) eligible to participate, of which n = 58 (32%) consented to participate. The recruitment rate was 6.4 per month. Due to the impact of COVID-19 on the study, recruitment took place over two separate phases in 2020 and 2021. Of the 25 participants completing the full study, 23 were female (mean age 60 years (SD 11.5)), with n = 11 allocated to intervention group and n = 14 to control. Intervention group participants completed 100% of sessions 1 & 2, 88% of session 3 and 81% of session 4. The study design and intervention were acceptable overall to participants, with enhancements suggested. The PIPPRA study to improve promote physical activity in people with RA who have low PA levels was feasible, acceptable and safe. Despite the impact of COVID-19 on the recruitment and retention of patients, the study provides preliminary evidence that this physiotherapist led BC intervention is feasible and a full definitive intervention should be undertaken. Health care professionals involved in the study delivery and the patient participants described a number of positive aspects to the study with some suggestions to enhance the design. These findings hence inform the design of a future efficacy-focused clinical trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune condition mainly affecting the joints and can lead to a 1.5–1.6 fold higher mortality rate than in the general population [1]. Prevalence of RA is varied with an average point and period prevalence of 51 in 10,000 and 56 in 10,00 reported in a review of studies from 1986 to 2014 [2].

Recommended management of RA includes pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments with physical activity (PA) being an important component in the non-pharmacological management of RA [3, 4]. However, people with RA tend to have low PA levels [5, 6] thus improving PA levels in this group is an important part of treatment.

To date, interventions targeting longer term PA change in people with RA have had some success [7, 8], with challenges in improving healthy PA (> or = 30 min, moderately intense activity, most days of the week) [7] and transitioning to and maintaining more intense levels of PA [8]. Adopting a behaviour change approach to PA promotion is a key aspect of better intervention design [9, 10]. Adopting the Behaviour Change Wheel [11] can guide the determination of the factors to be addressed in a BC intervention to promote PA. Health professional involvement with people with RA in promoting PA is one important aspect of intervention delivery [12]. In addition, targeting participants with the existing low levels of PA should be considered as low PA levels have been shown to be an independent risk factor for number of hospital admissions and duration of hospitalisation in people who have RA [13]. Therefore, increasing and maintaining PA levels in people with RA may serve to reduce healthcare costs and enhance the health outcomes of the RA population [14].

Guided by the Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions [15] the authors undertook extensive systematic literature reviews [9, 10], objective PA measurement validation [16] and qualitative interviews with people with RA [17] and with rheumatology health professionals [18] to design a robust intervention [19] to address the issues above. Following the completion of these underpinning studies, a novel BC physiotherapist led intervention for adults with RA to promote physical activity (PIPPRA study) was developed and a feasibility study was designed. The aim of this study was to explore the overall feasibility of PIPRRA with the following objectives: (1) to determine the number of eligible participants, the recruitment numbers and rate, protocol adherence; (2) to evaluate the acceptability of PIPPRA in both patients and HCPs involved in recruitment and delivery of the intervention and (3) to undertake exploratory analyses of the outcome data to develop a power calculation for a future trial.

Methods

Study design

The study design was a feasibility randomised trial with the published protocol (version 1) [19] and the final trial protocol registered on ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03644160. Ethical approval was granted by the University Hospital Limerick (UHL) Research Ethics Board (approval number 064/19). Reporting followed the relevant extensions of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials [20].

Participants and setting

Inclusion criteria for the intervention part of the study were: adults (over 18 years) with a diagnosis of RA based on the American College Rheumatology 2010 criteria and low PA levels using the Godin−Shephard Leisure−Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (GSLPAQ) [21]. Patients identified from clinic charts as having a diagnosis of RA were approached by the study research assistant who introduced the study and completed the GSLPA) with each patient. If the patient had a score of less than 14 on the GSLPAQ they were given an information leaflet on the study and any questions were answered. A consent form was given and a time was arranged for a follow-up call within the next week to determine the person’s interest or not in participating the in the study. Informed consent was then obtained prior to formal study enrolment at the arranged baseline meeting with the study team. Patients continued with their usual care throughout the study.

For the interview part of the study patients in both intervention and control arms were invited to participate following completion of the main study. Health care professionals involved in rheumatology clinics the patients were recruited from (rheumatologists, medical teams and nursing staff) as well as the sessional physiotherapists who delivered the intervention were invited to participate on completion of the study. Informed written consent was recorded for each participant in the interview part of the study.

The study was conducted at University Hospital Limerick (UHL), Ireland in the outpatient rheumatology department (recruitment) and the hospital’s Clinical Education and Research Centre (CERC) (intervention delivery and assessments). Participants were recruited from weekly outpatient rheumatology clinics in UHL across two periods (due to interruption from Covid-19) between October 2019 and March 2020 and November 2020 to May 2021 (9 months total).

Patient safety was monitored throughout the study by the study team. Discontinuation criteria were determined at the outset of the study as follows: a) immediate discontinuation will occur, regardless of the stage of the study, if participants develop any severe adverse events during the study which may or may not be related to the intervention—such as chest pain; b) Participants could also choose to discontinue the intervention at any time for any reason. The type and frequency of adverse events were recorded and reported to the study Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) if they occurred.

Randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding

The CERC Unit provided a computer randomisation system. Randomisation was performed by computer generated random numbers with a 1:1 allocation ratio to the intervention or control arms. The allocation sequence was generated independent of the study team. Allocations were stored in a locked cabinet. Participants were informed of allocation by the research assistant after completion of their baseline assessments. Each participant was assigned a code number, which was used on all outcome assessments in place of their names. The assessor was blinded to group allocation. The person assigning the allocations was blinded to allocation until after the participant was assigned. The statistician who completed the data analysis was blinded to group allocation.

Intervention and control group

The PIPPRA trial is a theoretically underpinned physiotherapist led BC intervention to promote PA delivered over 4 1:1 sessions by a sessional physiotherapist in person or virtually over an 8 week period. The intervention was tailored to each individual depending on the discussion with the sessional physiotherapist on the type of PA they were undertaking. Each session was a maximum of one hour. The original design was in-person intervention delivery only; however due to the timing of the study during the Covid-19 pandemic, virtual sessions were necessitated to ensure the completion of the study. Virtual sessions were delivered using WhatsApp video calls. The in-person sessions were delivered in a meeting room with minimal infrastructure and no exercise equipment. This was deliberate to ensure the transfer of the intervention delivery to any setting and eliminate the reliance on specialist settings or equipment.

PIPPRA comprises individual sessions based on the specific BC techniques, as described by the Behaviour Change Taxonomy [11]. A detailed description of the final programme is included in supplementary file 1 and in the protocol paper [19]. Briefly, across the 4 sessions participants were guided using a range of ‘education’ techniques’ (e.g. instruction on how to perform a behaviour, discussion on health consequences), ‘enablement’ techniques (e.g. goal setting, problem solving, action planning, feedback, self-monitoring, social comparison) and ‘modelling’ techniques. A PA behaviour plan was also prepared by each participant and reviewed at each session and adjusted as needed and agreed by the participant and therapist. Both control and intervention group received an information booklet about PA based on the existing guidelines for people with RA (Supplementary file 2).

Therapist intervention training

The sessional physiotherapist was trained in BC techniques and motivational interviewing by the study’s postdoctoral researcher and co-author (LL). The postdoctoral researcher was a qualified physiotherapist with a PhD in the area of behaviour change for PA in rheumatology and also co-applicant on the study and lead author on many of the underpinning studies. The sessional physiotherapists were newly qualified therapists with no experience in specialist rheumatology settings. The rationale for involving newly qualified therapists was to explore if a BC intervention could be delivered with minimal specialist training. A detailed session log of each session was maintained by the sessional physiotherapists (supplementary file 3a and 3b).

Modifications to study design due to COVID-19

COVID-19 restrictions in Ireland came into effect in March 2020 and necessitated a transition, after a 5 month pause of the study, from in-person to remote, virtual assessments and intervention delivery [22]. The COVID-19 pandemic also resulted in lost data as we were unable to follow-up some participants who withdrew from the study for reasons linked to Covid-19.

Data collection

The data collection took place at baseline (Time 0 (T0), 12 weeks (Time 1 (T1)) and 24 weeks (Time 2 (T2)). Questionnaires were completed via phone call with participants ActivPal devices were sent to and returned via post. The data were downloaded from the ActivPal to the study laptop and the output file was uploaded to the e-Case report form database (Clindox Limited, hosted by the University of Limerick encrypted server). Participant’s out of pocket expenses were reimbursed using a shopping voucher.

Primary outcomes

A number of feasibility targets were calculated:

Recruitment and retention

-

Feasible eligibility—the total number of eligible participants from UHL group rheumatology clinics

-

Recruitment rate—the number (%) of participants recruited and the rate of participants recruited to the study.

-

Refusal numbers—the number (%) of eligible participants that refused to participate and reasons why.

Protocol adherence

-

Minimum average attendance—the number of participants who attended over 80% of the intervention sessions.

-

Minimum outcome assessment target—retention of at least 80% of recruited participants with valid 12 (T1) and 24 (T2)—week primary outcome data, i.e. less than 20% attrition at outcome assessments at 12 and 24-week follow-up

Intervention acceptability

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken on completion of recruitment and the intervention with patients and the HCPs (rheumatology clinic medical team and nursing staff and sessional physiotherapists). Patients and HCPs were provided with verbal and written information about the study. Each participant provided informed consent prior to participation. The interviews aimed to determine patient and HCP acceptability of the intervention, understand some of the trial design and processes and to consider the acceptability of the secondary outcomes used. Interview questions for the interview guide (Supplementary file 4) were developed from an extensive literature review on behaviour change interventions to promote physical activity behaviour in people who have RA [9, 10] and from the previous qualitative research in this area [17, 18]. Interviews were audio-recorded and conducted by co-authors LL and S McK, chartered physiotherapists and researchers who have experience of undertaking and analysing qualitative interviews. Audio recordings from the semi-structured interviews were transcribed, anonymised and saved to a password protected laptop from University of Limerick. Each interviewee was offered a copy of their transcript to review and advised to amend the transcript if necessary. Once interviewees were satisfied that the transcript reflected their views and opinions accurately the finalised transcript was included in data analysis. Preliminary data analysis was conducted concurrently with data collection, to enhance understanding about the questions being asked and facilitated minor revisions of the questions. The analytical approach for this data was content analysis. NVivo (version 14 QSR International) was used to support the qualitative analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Physical activity

The ActivPAL™ (PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK) measured time spent sitting, standing, lying and time spent in moderate and vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity (MVPA) [16]. It has been validated in RA samples [23]. The ActivPAL™ is a small, lightweight activity monitor that uses proprietary algorithms. It is a tri-axial accelerometer that produces a signal related to thigh inclination and needs no calibration before use. Recordings were processed for daily minutes of moderate to vigorous PA. The ActivPAL™ was worn for 8 days beginning week 1 before the start of intervention (T0, for 8 days 1-week post-intervention (T1) and at the 24-week assessment (T2). The first 24 h of recording were not included in the analysis to minimise the effects of reactivity. A minimum recording duration of 3 days from the 7-day period, including at least one weekend day was required for data processing; samples of lower than 3 days were not included.

The Yale Physical Activity Survey (YPAS) [24] measured participants self-report PA and has been used in the previous arthritis studies and older adults [25, 26]. The 2-part YPAS measures PA over a time period of a typical recent week (part 1) and from the past month (part 2). The total energy expenditure per week was calculated from part 1 of the questionnaire for each participant at each time point.

Psychological beliefs

The theory of Planned Behaviour Questionnaire (TPBQ) consists of three elements; beliefs about the likely consequences of the behaviour (behavioural beliefs), beliefs about the normative expectations of others (normative beliefs), and beliefs about the presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of the behaviour (control beliefs) [27]. Behavioural beliefs produce a favourable or unfavourable attitude toward the behaviour; normative beliefs result in perceived social pressure or subjective norm; and control beliefs give rise to perceived behavioural control. Thus, attitude toward the behaviour, subjective norm, and perception of behavioural control led to the formation of a behavioural intention. The TPBQ aims to capture all three elements which contribute to behavioural intention.

Disease activity

The Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) [28] was used to combine single measures into an overall, continuous measure of RA disease activity. The DAS28 includes a 28 tender joint count, a 28 swollen joint count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a general health assessment on a visual analogue scale. After study interruption due to COVID-19 this measure was not recorded as participants were not able to attend the unit physically for blood draws.

Pain

Pain was recorded using a 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS), which is sensitive to detecting changes in pain in inflammatory conditions and has good reliability and validity [29].

Fatigue

The Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional Questionnaire (BRAF-MDQ) [30] measured the impact of fatigue for people with RA and disease specific. It has acceptable to good convergent validity [31] and consists of 20 items combined to create 5 scores, where a higher score reflects worse fatigue. The total score range is 0–70.

Sleep

Sleep was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [32] and has been used in previous arthritis studies [33, 34]. It is a 19-item self-rated questionnaire for evaluating subjective sleep quality over the previous month. The 19 questions are combined into 7 clinically-derived component scores, each weighted equally from 0 to 3. The clinical and psychometric properties of the PSQI have been formally evaluated by several research groups [33].

Quality of life

The Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RAQoL) measured disease related quality of life [35] on ADLs, social interaction, emotional well-being, and relationships. The questionnaire consists of 30 statements that have a yes/no response. Items are scored one for yes and zero for no. Scores for each item are summed to give an overall quality of life score with a higher score indicating a poorer quality of life.

Sample size and data analysis

The target sample size for the pilot study of 40 participants, with 20 participants in both the control and intervention groups was determined pragmatically. This sample size was expected to provide sufficient data to meet the primary outcomes and was in the appropriate range for pilot studies [36]. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the recruitment and retentions rates and for the secondary outcomes. Data analysis was undertaken in SPSS version 27 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA). Given the small sample size it was not deemed appropriate to present differences between arms.

Progression criteria

The following criteria were agreed for progression to a full trial.

-

1.

In order for a definitive trial to be feasible we project that we need to recruit participants at a minimum recruitment rate of 4 per month; i.e. 48 per year. The primary feasibility target is a minimum recruitment rate of 4 participants per month.

-

2.

Following recruitment of participants, a minimum attendance at 100% of the intervention sessions is expected. A second feasibility target is thus a minimum average attendance by recruited participants of 100% of the intervention sessions.

-

3.

Outcome assessment at 12-week follow-up—retention of at least 80% of recruited participants with valid outcome assessments, i.e. less than 20% attrition. Thus a third feasibility target is a minimum retention of 80% of recruited participants providing valid 12-week outcome data

Results

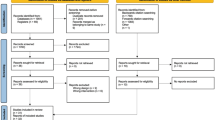

Recruitment occurred over two separate time periods between October 2019 and March 2020 and November 2020 to May 2021 (9 months total). A total of 320 participants were identified at the outpatient clinics as potentially eligible. Baseline demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. The flow of participants through the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Primary outcome measures

Recruitment and retention

Of the total assessed for eligibility (n = 320), n = 262 were excluded with 137 of these not meeting the inclusion criteria and 125 declining the invitation to participate. The remaining eligible participants (n = 58 (55%) consented to participate with a recruitment rate of 6.4 per month. Owing to impact of COVID-19 on the study n = 25 (43%) participants completed the study (n = 11 (44%) in intervention and n = 14 (56%) in control). Of the 25, n = 23 (92%) were female, the mean age was 60 years (SD 11.5). Further details of the demographic profile of the participants is shown in Table 1. No adverse events were reported.

Protocol adherence

Intervention group participants completed 100% of session 1 and 2, 88% session 3 and 81% session 4. Participants reported no adverse events (AEs) during the 24-week intervention period. The percentage of participants who completed assessments at T1 was 53% and 69% at T2.

Secondary outcome measures

Descriptive statistics for secondary outcomes are reported in Table 2. In line with the objectives of the study the inclusion of outcomes was to provide preliminary evidence of the efficacy of the intervention and estimation of the population standard deviation for objective PA to inform sample size calculations for a future definitive trial. No within group or between group analyses of differences was undertaken as this was not the aim of the study.

Acceptability of the intervention

Interviews were undertaken with 12 patients (4 intervention and 8 control), with 6 HCPs (3 sessional physiotherapists, 2 rheumatologists and 1 rheumatology nurse). Following the transcription of all interviews, each transcript was read and re-read by one member of the research team (AF). Using content analysis segments of the transcripts were coded and grouped in the subsequent stages of analysis where the initial sets of codes were reduced down into summary form to form subcategories.

Several categories were identified in relation to the factors which prompted acceptability of this intervention for the participants (Table 3) and the HCPs (Table 4). The categories identified from the participant interviews were (i) positive effect of outcome measures to participation (ii) acceptability of information (iii) physiotherapist as a suitable guide (iv) recruitment process to be face-to-face and the (v) positive effect of social interactions on physical activity habits. The sessional physiotherapist and HCPs interviews discussed a number of additional categories: i) the intervention setting ii) resources available to support the intervention iii) enhanced communication and enhancements to recruitment. Overall, across both groups the intervention and outcome measures were acceptable, with suggestions made to enhance recruitment and intervention delivery.

Progression to full scale trial

Three criteria were stated at the outset to determine if a future definitive trial would be feasible. The stated recruitment rate of 4 participants per month was exceeded (6.4 per month). The second criterion was a minimum average attendance by recruited participants of 100% of the intervention sessions. This criterion was not met for all 4 sessions (intervention group participants completed 100% of session 1 & 2, 88% session 3 and 81% session 4). The final criterion was a minimum retention of 80% of recruited participants providing valid 12-week outcome data. This was not met as the percentage of participants who completed assessments at T1 was 53% and 69% at T2.

Power and sample size calculations for future definitive intervention

The standard deviation of the step count was calculated at approximately 2500 steps, hence, to detect a difference of at least 1000 steps in a double-armed trial, at a 5% level of significance and with an 80% power, a sample of size of 200 (balanced design, 100 in each group) will be required in a future full-scale clinical trial.

Discussion

The study objectives were to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a BC intervention in improving PA in people with RA who were physically inactive. The study achieved its objectives on feasibility and determined a recruitment rate of 6.4 participants per month. We exceeded the target sample size, but had to exclude a large number of participants from the data analysis due to the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on access to clinics for recruitment and treatment rooms for intervention delivery and assessments. A commonly reported issue with the conduct of RCTs is that recruitment is often slower or more difficult than expected [37, 38]. However, the PIPPRA study achieved a higher than expected recruitment rate from a single rheumatology unit indicating the feasibility of the recruitment in a larger study. The restrictions also impacted the achievement of the minimum outcome assessment target.

We were also able to calculate the sample size for a definitive intervention using data from other studies as well as PIPPRA to address concerns on the high variability of the PIPPRA data. The secondary measures were practical to incorporate into the study design and even with the change to virtual delivery and assessment only one outcome measure (DAS28) had to be removed. As this study was a feasibility trial the secondary outcome measures were completed for the purpose of estimation of standard deviations only and to inform sample size calculations. No conclusion on the effectiveness of the interventions can be drawn at this feasibility stage. Although only one of the 3 pre-set criteria for progression to full trial were met, the two that were not met (attendance at 100% of intervention sessions and 80% of recruited participants providing valid 12-week outcome data) were impacted by COVID-19 related issues. Given the pandemic context the actual results for these 2 criteria still achieved good results despite the circumstances (88% session 3 and 81% session 4 completion and completion of assessments at T1 was 53% and 69% at T2).

The PIPPRA study was considered acceptable to the participants, the sessional physiotherapists and the rheumatology health care professionals involved in recruitment and ongoing usual care for the participants. Enhancements to the design that were suggested included allowing more time for change in behaviour to be seen by extending the time between sessions 3 and 4. Establishing a way for the sessional physiotherapists to communicate with each other before and during the study was also proposed. A desire for more baseline information as would be standard in clinical care as well as a greater breadth of resources to include visual as well as written materials to support intervention delivery were also suggested as enhancements. From the patient perspective the outcome measures were considered acceptable with some participants advising on the need to consider the length of time the assessments took as it was too onerous. Participants valued the physiotherapists guidance reinforcing the need for physiotherapist interventions to improve physical activity. There was not universal agreement that virtual intervention only was the preferred choice suggesting the option of in person and/or virtual delivery should be considered in future interventions. This resonates with other research [39] which evaluated in person and videoconferencing delivery of an education programme for people with inflammatory arthritis and found no difference in outcomes between the two modes. Similarly, a study [40] on the perspectives of people with Psoriatic Arthritis on virtual consultation during COVID-19 found a wide range of perspectives on its benefits. The value of the social side of exercise in future interventions should also be considered to add to the experience and enjoyment of the intervention.

Therefore, the data from this study indicates that the PIPPRA intervention was both feasible, acceptable to and safe for people with RA who were physically inactive.

The PIPPRA study pilot trial methods provide valuable learnings for others designing trials of interventions in lifestyle/behaviour change areas for a range of cohorts, including non-clinical populations. The inclusion of a screening tool (GSLPAQ) to target people with RA who were physically inactive is a valuable addition to the literature on improving PA in people with inflammatory arthritis. A criticism of previous studies aiming to improve PA levels has been that participants included were already engaged in some level of PA and targeting those with low or now PA profile is important. Hence the PIPPRA study was designed to only include those with low levels of PA. The GSLPAQ was a useful tool in screening—a future study should use an additional tool alongside the GSLPAQ to explore the sensitivity of the GSLPAQ.

Study limitations

Participants in this study were independently mobile and able to be active and therefore are not representative of the total RA population particularly those with greater mobility limitations and with a variety of activity levels. Hence, a selection bias in the sampling should be noted.

The sample size of 40 patients was not reached due to the interruption of COVID-19 on the study. While the study’s feasibility objectives were still met the results on the secondary objectives need to be interpreted with caution.

As the study examined an intervention delivered by a physiotherapist compared to a control intervention of a PA leaflet, it was not possible to blind participants to the intervention. This is an accepted design limitations of this type of intervention.

The study was designed to consider pragmatic aspects of delivery of this type of care in healthcare settings including delivery by clinicians who are not experts in behaviour change. This presents a possible source of bias in differences in how the sessional physiotherapists who delivered the intervention. As this is a feasibility study the effectiveness of the intervention was not the primary focus and hence this possible bias does not impact the study results.

COVID-19 disrupted the study in many ways [20] and as described previously—complete data sets were not available for all participants enrolled pre COVID-19. Overall, despite the impact of COVID-19, there are no outstanding uncertainties relating to the feasibility of the study.

The number of interviews with participants involved less participants from the intervention than the control arm. Despite attempts to increase the number of intervention participants it was not possible due to the timing of the end of the study.

Conclusion

The PIPPRA study to improve promote physical activity in people with RA who have low PA levels was feasible, acceptable and safe. Despite the impact of COVID-19 on the recruitment and retention of patients, the study provides preliminary evidence that this physiotherapist led BC intervention is feasible and a full definitive intervention should be undertaken. Health care professionals involved in the study delivery and the patient participants described a number of positive aspects to the study with some suggestions to enhance the design. These findings hence inform the design of a future efficacy-focused clinical trial.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T (2008) Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol 26(Suppl. 51):S35–S61

Almutairi K, Nossent J, Preen D et al (2021) The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of population-based studies. J Rheumatol 48(5):669–676. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.200367

Fraenkel L, Bathon J, England B et al (2021) American College of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 73:1108–1123. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24596

Osthoff A-K, Niedermann K, Braun J et al (2018) EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77(9):1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585

Tierney M, Fraser A, Kennedy N (2012) Physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Phys Act Health 9(7):1036–1048. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.9.7.1036

Sokka T, Hakkinen A, Kautiainen H et al (2008) Physical inactivity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: data from twenty-one countries in a cross-sectional, international study. Arthritis Rheum 59:42–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23255

Brodin N, Eurenius E, Jensen I et al (2008) Coaching patients with early rheumatoid arthritis to healthy physical activity: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 59(3):325–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23327

Knittle K, De Gucht V, Hurkmans E et al (2015) Targeting motivation and self-regulation to increase physical activity among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rheum 34(2):231–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-013-2425-x

Larkin L, Gallagher S, Cramp F et al (2015) Behaviour change interventions to promote physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 35(10):1631–1640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-015-3292-3

Larkin L, Kennedy N, Gallagher S (2015) Promoting physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a narrative review of behaviour change theories. Disabil Rehabil 37(25):2359–2366. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1019011

Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 6(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Swärdh E, Nordgren B, Opava CH et al (2020) “A necessary investment in future health”: perceptions of physical activity maintenance among people with rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther 100(12):2144–2153. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa176

Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Treharne GJ et al (2011) Disease activity and low physical activity associate with number of hospital admissions and length of hospitalisation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 13(3):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3390

Metsios G, Kitas G (2018) Physical activity, exercise and rheumatoid arthritis: effectiveness, mechanisms and implementation. Best Prac Res Clin Rheum 32(5):669–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2019.03.013

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S et al (2013) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud 50(5):587–592. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

Larkin L, Nordgren B, Purtill H et al (2016) Criterion validity of the activPAL activity monitor for sedentary and physical activity patterns in people who have rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther 96(7):1093–1101. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20150281

Larkin L, Kennedy N, Fraser A et al (2016) “It might hurt, but still it’s good”: People with rheumatoid arthritis beliefs and expectations about physical activity interventions. J Health Psychol 22(13):1678–1690. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316633286

Larkin L, Gallagher S, Fraser A et al (2017) If a joint is hot it’s not the time: health professionals’ views on developing an intervention to promote physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Disabil Rehabil 39(11):1106–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1180548

Larkin L, Gallagher S, Fraser A et al (2017) Community-based intervention to promote physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis (CIPPA-RA): a study protocol for a pilot randomised control trial. Rheumatol Int 37(12):2095–2103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3850-y

Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ et al (2016) CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 355:i5239. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5239

Godin G (2011) The Godin–Shephard leisure–time physical activity questionnaire. Health Fit J Can 4(1):18–22. https://doi.org/10.14288/hfjc.v4i1.82

Larkin L, Raad T, Moses A et al (2023) The impact of COVID-19 on clinical research: the PIPPRA and MEDRA experience [version 2; peer review: 2 approved: 2]. HRB Open Res 4:55. https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13283.2

Bassett DR Jr, John D, Conger SA et al (2014) Detection of lying down, sitting, standing, and stepping using two activPAL monitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46(10):2025–2029. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000326

Dipietro L, Caspersen CJ, Ostfeld AM et al (1993) A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 25(5):628–642

Colbert LH, Matthews CE, Havighurst T et al (2011) Comparative validity of physical activity measures in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43(5):867–876. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fc7162

Larkin L, Gallagher S, Fraser AD et al (2016) Relationship between self-efficacy, beliefs, and physical activity in inflammatory arthritis. Hong Kong Physiother J 34:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkpj.2015.10.001

Francis, J, Eccles, MP, Johnston M et al (2004) Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour: a manual for health services researchers. Quality of life and management of living resources; Centre for Health Services Research. Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Van Riel PL (2014) The development of the disease activity score (DAS) and the disease activity score using 28 joint counts (DAS28). Clin Exp Rheumatol 32(5):S65–S74

Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T et al (2011) Measures of adult pain: visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form mcgill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPS), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res 63(Suppl 11):S240–S252. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20543

Hewlett S, Dures E, Almeida C (2010) Measures of fatigue: Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue multi-dimensional questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue numerical rating scales (BRAF NRS) for severity, effect, and coping, Chalder fatigue questionnaire (CFQ), checklist individual strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), fatigue severity scale (FSS), functional assessment chronic illness therapy (fatigue) (FACIT-F), multi-dimensional assessment of fatigue (MAF), multi-dimensional fatigue inventory (MFI), pediatric quality of life (PedsQL) Multi-dimensional fatigue scale, profile of fatigue (ProF), short form 36 vitality subscale (SF-36 VT), and visual analog scales (VAS). Arthritis Care Res 63(Suppl 11):S263–S286. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20579

Nicklin J, Cramp F, Kirwan J et al (2010) Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study to evaluate the Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue multi-dimensional questionnaire, visual analog scales, and numerical rating scales. Arthritis Care Res 62(11):1559–1568. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20282

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH et al (1989) The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH et al (1991) Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI). Sleep 14(4):331–338

McKenna SG et al (2021) The feasibility of an exercise intervention to improve sleep (time, quality and disturbance) in people with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot RCT. Rheumatol Int 41(2):297–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04760-9

Tijhuis GJ, de Jong Z, Zwinderman AH et al (2001) The validity of the rheumatoid arthritis quality of life (RAQoL) questionnaire. Rheumatol 40(10):1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/40.10.1112

Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC (2011) The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res 45(5):626–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008

Watson JM, Torgerson DJ (2006) Increasing recruitment to randomised trials: a review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 19(6):34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-34

Treweek S, Lockhart P, Pitkethly M et al (2013) Methods to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 3:e002360. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002360

Kennedy CA, Warmington K, Flewelling C et al (2017) A prospective comparison of telemedicine versus in-person delivery of an interprofessional education program for adults with inflammatory arthritis. J Telemed Telecare 23(2):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16635342

Jethwa H, Brooke M, Parkinson A et al (2022) Patients’ perspectives of telemedicine appointments for psoriatic arthritis during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of a patient-driven pilot survey. BMC Rheumatol 6:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00242-y

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the following collaborators – University Hospitals Group Limerick (Clinical Research Support Unit, Department of Rheumatology), Arthritis Ireland, Health Services Executive Rheumatology Care Programme, Irish Society of Chartered Physiotherapists Rheumatology Interest Group, Irish Society of Rheumatology, Dr Nina Brodin, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden and Dr Thijs Swinnen, KU Leuven, Belgium

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. This study was funded by the Health Research Board, Ireland (DIFA_2018_004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NK, AF, BE, LL, SG, LG conceptualized and designed the study. LL, PG, TP, AM, S McK and NK were involved in data collection. NK, LL, SMCK drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. No AI or other software was used for writing or editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. No part of this work is copied or published elsewhere in whole or in part and it is entirely the work of this group.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the University Hospital Limerick (UHL) Research Ethics Board 064/19.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Larkin, L., McKenna, S., Pyne, T. et al. Promoting physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis through a physiotherapist led behaviour change-based intervention (PIPPRA): a feasibility randomised trial. Rheumatol Int 44, 779–793 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05544-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05544-1