Abstract

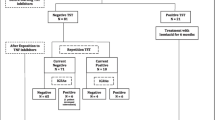

This study aimed to compare Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) and QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT–GIT) test in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and spondyloarthritis (SpA) patients scheduled for biological and targeted synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in a Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-vaccinated population. Adult RA (n = 206) and SpA (n = 392) patients from the TReasure database who had both TST and QFT–GIT prior to initiation of biological and targeted synthetic DMARDs were included in the study. Demographic and disease characteristics along with pre-biologic DMARD and steroid use were recorded. The distribution of TST and performance with respect to QFT–GIT were compared between RA and SpA groups. Pre-biologic conventional DMARD and steroid use was higher in the RA group. TST positivity rates were 44.2% in RA and 69.1% in SpA for a 5 mm cutoff (p < 0.001). Only 8.9% and 15% of the patients with RA and SpA, respectively, tested positive by QFT–GIT. The two tests poorly agreed in both groups at a TST cutoff of 5 mm and increasing the TST cutoff only slightly increased the agreement. Among age, sex, education and smoking status, pre-biologic steroid and conventional DMARD use, disease group, and QFT–GIT positivity, which were associated with a 5 mm or higher TST, only disease group (SpA) and QFT–GIT positivity remained significant in multiple logistic regression. TST positivity was more pronounced in SpA compared to that in RA and this was not explainable by pre-biologic DMARD and steroid use. The agreement of TST with QFT–GIT was poor in both groups. Using a 5 mm TST cutoff for both diseases could result in overestimating LTBI in SpA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and materials

The data underlying this article were accessed from the TReasure database (URL: https://www.trials-network.org/treasure). The derived data generated in this research will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of rheumatology

- ASAS:

-

Assessment of spondyloarthritis International Society

- BCG:

-

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention

- DMARD:

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

- EULAR:

-

European league against rheumatism

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IFN:

-

Interferon

- IGRA:

-

Interferon-γ release assay

- LTBI:

-

Latent tuberculosis ınfection

- NTM:

-

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria

- QFT–GIT:

-

QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube Test

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SpA:

-

Spondyloarthritis

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- TST:

-

Tuberculin skin test

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization (2018) Latent tuberculosis infection—Updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260233 Accessed 3 April 2022

Iannone F, Cantini F, Lapadula G (2014) Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis and prevention of reactivation in rheumatic patients receiving biologic therapy: international recommendations. J Rheumatol Suppl 91:41–46. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140101

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC et al (2016) 2015 American college of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 68:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39480

Koike R, Takeuchi T, Eguchi K, Miyasaka N, College J, of Rheumatology, (2007) Update on the Japanese guidelines for the use of infliximab and etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 17:451–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10165-007-0626-3

Australian Rheumatology Association (2018) Screening for Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) and its management in Inflammatory arthritis patients. https://rheumatology.org.au/Portals/2/Documents/Public/Professionals/SCREENINGFORLATENTTUBERCULOSISINFECTION_Jan18.pdf?ver=2021-06-28-141621-710 Accessed 3 April 2022

Parisi S, Bortoluzzi A, Sebastiani GD, Conti F, Caporali R, Ughi N et al (2019) The Italian society for rheumatology clinical practice guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatismo 71:22–49. https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2019.1202

Bombardier C, Hazlewood GS, Akhavan P, Schieir O, Dooley A, Haraoui B et al (2012) Canadian rheumatology association recommendations for the pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis with traditional and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: part II safety. J Rheumatol 39:1583–1602. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.120165

T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı Türkiye Halk Sağlığı Kurumu (2016) Anti-TNF kullanan hastalarda tüberküloz rehberi. [Turkish] http://www.romatoloji.org/Dokumanlar/Site/ATKHTR.pdf Accessed 3 April 2022

Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, Cohn DL, Daley CL, Desmond E et al (2017) Official American thoracic society/infectious diseases society of america/centers for disease control and prevention clinical practice guidelines: diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 64:111–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw778

2000 Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 161: S221 S247 https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600.

Lee E, Holzman RS (2002) Evolution and current use of the tuberculin test. Clin Infect Dis 34:365–370. https://doi.org/10.1086/338149

Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, LoBue P, Goldberg S, Castro K, IGRA Expert Committee; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010) Updated guidelines for using Interferon gamma release assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 59:1–25

Mahomed H, Hawkridge T, Verver S, Abrahams D, Geiter L, Hatherill M et al (2011) The tuberculin skin test versus QuantiFERON TB Gold® in predicting tuberculosis disease in an adolescent cohort study in South Africa. PLoS ONE 6:e17984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017984

Sharma SK, Vashishtha R, Chauhan LS, Sreenivas V, Seth D (2017) Comparison of TST and IGRA in diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in a high TB-burden setting. PLoS ONE 12:e0169539. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169539

Kampmann B, Whittaker E, Williams A, Walters S, Gordon A, Martinez-Alier N et al (2009) Interferon-gamma release assays do not identify more children with active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Eur Respir J 33:1374–1382. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00153408

Brock I, Weldingh K, Lillebaek T, Follmann F, Andersen P (2004) Comparison of tuberculin skin test and new specific blood test in tuberculosis contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170:65–69. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200402-232OC

Arend SM, Thijsen SF, Leyten EM, Bouwman JJ, Franken WP, Koster BF et al (2007) Comparison of two interferon-gamma assays and tuberculin skin test for tracing tuberculosis contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:618–627. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200608-1099OC

Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Meywald-Walter K, Gottschalk R, Nienhaus A (2009) Comparative performance of tuberculin skin test, QuantiFERON-TB-Gold In Tube assay, and T-Spot.TB test in contact investigations for tuberculosis. Chest 135:1010–1018. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2048

Hill PC, Jeffries DJ, Brookes RH, Fox A, Jackson-Sillah D, Lugos MD et al (2007) Using ELISPOT to expose false positive skin test conversion in tuberculosis contacts. PLoS ONE 2:e183. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000183

Erol S, Ciftci FA, Ciledag A, Kaya A, Kumbasar OO (2018) Do higher cut-off values for tuberculin skin test increase the specificity and diagnostic agreement with interferon gamma release assays in immunocompromised Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccinated patients? Adv Med Sci 63:237–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advms.2017

Jeong DH, Kang J, Jung YJ, Yoo B, Lee CK, Kim YG et al (2018) Comparison of latent tuberculosis infection screening strategies before tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in inflammatory arthritis: IGRA-alone versus combination of TST and IGRA. PLoS ONE 13:e0198756. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198756

Kim EY, Lim JE, Jung JY, Son JY, Lee KJ, Yoon YW et al (2009) Performance of the tuberculin skin test and interferon-gamma release assay for detection of tuberculosis infection in immunocompromised patients in a BCG-vaccinated population. BMC Infect Dis 9:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-9-207

Hanta I, Ozbek S, Kuleci S, Seydaoglu G, Ozyilmaz E (2012) Detection of latent tuberculosis infection in rheumatologic diseases before anti-TNFα therapy: tuberculin skin test versus IFN-γ assay. Rheumatol Int 32:3599–3603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-2243-x

Kurti Z, Lovasz BD, Gecse KB, Balint A, Farkas K, Morocza-Szabo A et al (2015) Tuberculin skin test and quantiferon in BCG vaccinated, ımmunosuppressed patients with moderate-to-severe ınflammatory bowel disease. J Gastrointest Liver Dis 24:467–472. https://doi.org/10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.244.bcg

Ai JW, Ruan QL, Liu QH, Zhang WH (2016) Updates on the risk factors for latent tuberculosis reactivation and their managements. Emerg Microbes Infect 5:e10. https://doi.org/10.1038/emi.2016.10

Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Dubreuil M, Yu D, Khan MA et al (2019) 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 71:1599–1613. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41042

Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, Gladman DD, Deal C, Deodhar A et al (2019) 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National psoriasis foundation guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 71:2–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23789

Marchesoni A, Olivieri I, Salvarani C, Pipitone N, D’Angelo S, Mathieu A et al (2017) Recommendations for the use of biologics and other novel drugs in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: 2017 update from the Italian society of rheumatology. Clin Exp Rheumatol 35:991–1010

Kalyoncu U, Taşcılar EK, Ertenli Aİ, Dalkılıç HE, Bes C, Küçükşahin O et al (2018) Methodology of a new inflammatory arthritis registry: treasure. Turk J Med Sci 48:856–861. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-1807-200

Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovitz J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd et al (2010) 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 62:2569–2581. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27584

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Akkoc N, Brandt J, Chou CT et al (2011) The assessment of spondyloarthritis international society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis 70:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.133645

T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı. Tüberküloz Tanı ve Tedavi Rehberi (2019) [Turkish] https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/depo/birimler/tuberkuloz_db/haberler/Tuberkuloz_Tani_Ve_Tedavi_Rehberi_/Tuberkuloz_Tani_ve_Tedavi_Rehberi_08.07.2019_Yuksek_KB.pdf Accessed 3 April 2022

Uçan ES, Sevinç C, Abadoğlu Ö, Arpaz S, Ellidokuz H (2000) Interpretation of tuberculin skin tests, country standards and new requirements. Toraks 1:25–29

Bozkanat E, Çiftçi F, Apaydın M, Kartaloğlu Z, Tozkoparan E, Deniz Ö et al (2005) İstanbul il merkezindeki bir askeri okulda tüberkülin cilt testi taraması. Tüberk Toraks 53:39–49

İmre A, Arslan-Gülen T, Koçak M, Baş-Şarahman E, Kayabaş Ü (2020) Examination of tuberculin skin test results of health care workers in a hospital and healthy individuals who are not in risk of tuberculosis. Klimik Derg 33:19–23

Kazancı F, Güler E, Dağlı CE, Garipardıç M, Davutoğlu M, İspiroğlu E et al (2011) The prevalence of tuberculin skin test positivity and the effect of BCG vaccinations on tuberculin induration size in the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey. Turk J Med Sci 41:711–718. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-1008-1030

Rose DN, Schechter CB, Adler JJ (1995) Interpretation of the tuberculin skin test. J Gen Intern Med 10:635–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02602749

Wong SH, Gao Q, Tsoi KK, Wu WK, Tam LS, Lee N et al (2016) Effect of immunosuppressive therapy on interferon γ release assay for latent tuberculosis screening in patients with autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 71:64–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207811

Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE (2002) Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 46:2287–2293. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10524

Glück T, Müller-Ladner U (2008) Vaccination in patients with chronic rheumatic or autoimmune diseases. Clin Infect Dis 46:1459–1465. https://doi.org/10.1086/587063

Meroni PL, Zavaglia D, Girmenia C (2018) Vaccinations in adults with rheumatoid arthritis in an era of new disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Clin Exp Rheumatol 36:317–328. https://doi.org/10.1086/587063

Souto A, Maneiro JR, Salgado E, Carmona L, Gomez-Reino JJ (2014) Risk of tuberculosis in patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases treated with biologics and tofacitinib: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and long-term extension studies. Rheumatology 53:1872–1885. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu172

Duman N, Ersoy-Evans S, Karadag O, Aşçıoğlu S, Sener B, Kiraz S et al (2014) Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis patients in a tuberculosis-endemic country: a comparison of the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube Test and tuberculin skin test. Int J Dermatol 53:1286–1292. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.12522

World Health Organization (2021) Global tuberculosis report 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/346387 Accessed 3 April 2022

Cantini F, Nannini C, Niccoli L, Iannone F, Delogu G, Garlaschi G et al (2015) Guidance for the management of patients with latent tuberculosis infection requiring biologic therapy in rheumatology and dermatology clinical practice. Autoimmun Rev 14:503–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.011

Diel R, Goletti D, Ferrara G, Bothamley G, Cirillo D, Kampmann B et al (2011) Interferon-γ release assays for the diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 37:88–99. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00115110

Kim HC, Jo KW, Jung YJ, Yoo B, Lee CK, Kim YG et al (2014) Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection before initiation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy using both tuberculin skin test and QuantiFERON-TB Gold In Tube assay. Scand J Infect Dis 46:763–769. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365548.2014.938691

Lee H, Park HY, Jeon K, Jeong BH, Hwang JW, Lee J et al (2015) QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube assay for screening arthritis patients for latent tuberculosis infection before starting anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment. PLoS ONE 10:e0119260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119260

Soare A, Gheorghiu AM, Aramă V, Bumbăcea D, Dobrotă R, Oneaţă R et al (2018) Risk of active tuberculosis in patients with inflammatory arthritis receiving TNF inhibitors: a look beyond the baseline tuberculosis screening protocol. Clin Rheumatol 37:2391–2397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3916-y

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: UI, HE, UK. Data acquisition and analysis: UI, ÖK, HE, SA, LK, UK. Data interpretation: UI, ÖK, HE, OK, SSK, AE, CB, NAK, ED, SA, RM, MC, TK, EG, GK, DE, PA, LK, IE, VY, AA, SK, UK. Drafting and critical review: UI, ÖK, HE, OK, SSK, AE, CB, NAK, ED, SA, RM, MC, TK, EG, GK, DE, PA, LK, IE, VY, AA, SK, UK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Hacettepe University Institutional Review Board (KA17/058, May 2017) and Ministry of Health of Turkey (93189304-14.03.01, October 2017).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient regarding the use of clinical data for research purposes. The study was in accordance with the 2013 amendment of the Helsinki declaration.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

296_2022_5134_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary file1 Supplementary Table 1. Comparison of the study groups with entire RA and SpA patients in terms of demographic data, disease-related features, TST and QFT–GIT results, and LTBI treatment rates (DOCX 15 kb)

296_2022_5134_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Supplementary file2 Supplementary Table 2. Performance of TST to predict QFT–GIT for 5, 10, and 15 mm cutoff values (DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

İlgen, U., Karadağ, Ö., Emmungil, H. et al. Tuberculin skin test before biologic and targeted therapies: does the same rule apply for all?. Rheumatol Int 42, 1797–1806 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05134-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05134-z