Abstract

Understanding the impact of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) has become increasingly important among aging populations around the world, and Korea is no exception. This study was conducted to estimate total annual patient costs associated with RHD in Korea for 2008 using nationally representative data. The subjects were South Korean citizens with RHD (ICD-10 codes I01-I09). The primary information for this study was obtained from claims data compiled by the National Health Insurance Corporation of Korea. Direct medical care costs were estimated using expenses paid by insurers and patients for non-covered care and pharmaceutical costs. Direct non-medical costs were estimated using data on transportation costs for hospital visits and costs for caregivers. Indirect costs included the costs of productivity loss and premature death in RHD patients. The economic burden of RHD in 2008 was estimated at $67.25 million US dollars. The indirect costs amounted to 39.04 % (US $26.26 million) of the total RHD costs. When stratified by age, the costs incurred by the group of patients older than 60 years were US $31.63 million. The prevalence of the disease in the same age group was 791.07 cases per 100,000 people. This study confirms that the prevalence of RHD was highest in patients older than 60 years in 2008. Furthermore, the patterns of disease in South Korea were similar to patterns observed in other high-income countries. These findings indicate that secondary prevention strategies for the early detection of RHD are needed in South Korea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is a condition of long-term damage in cardiac muscle and cardiac valves due to rheumatic fever [1]. According to some studies, rheumatic fever develops into rheumatic heart disease in approximately 60 % of cases [2]. A recent study reports that rheumatic fever and RHD are the main causes of morbidity and mortality among diseases resulting from Group A Streptococcus infections [3].

Since high-income countries have a lower incidence of RHD than low-income countries, RHD is often excluded from the central issues of public health policies in high-income countries. Although the contribution of RHD to mortality and morbidity might be overlooked without echocardiography, the Euro Heart Survey suggests that there is a close correlation between degenerative valvular disease and increased life expectancy [4, 5]. All these facts indicate that the role of RHD as an important public health concern should be reconsidered in high-income countries.

Accordingly, this study estimates the extent of the economic burden of RHD on patients in Korea using a variety of materials that represent the national situation in Korea, including National Health Insurance claims data and Health Insurance Reviews and Assessment data. The data are based on the prevalence of RHD in Korea.

Methods

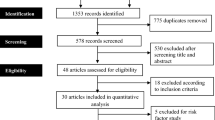

This study employed a top-down approach to attribute the total expenditure of RHD based on data about prevalence, service utilization, and other aspects of the disease.

The estimate of total cost was obtained for all of South Korea in 2008 (the base year) using a societal perspective. The information was mainly covered by the National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC) of Korea and the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) service. To overcome some limitations of these sources in the provision of primary data, the Korea Health Panel survey was used.

South Korea has a single insurer system, the NHIC, in which 97 % of the population participates. Therefore, data from the NHIC are representative of most medical expenses in Korea [6, 7]. In addition, this study utilized data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) service. HIRA was established to review medical fees and to evaluate the appropriateness of healthcare benefits received by beneficiaries [8].

This study mainly analyzed data from insurance claims and pharmaceutical costs to calculate the total medical costs of RHD for patients. Even though the claims data from the NHIC and HIRA cover most cases of RHD due to the characteristics of Korea’s system of Social Health Insurance, the information provided by the National Health Insurance Corporation does not take into account any non-covered service costs, transportation expenses, or caregiver costs. Thus, it is difficult to estimate total direct costs according to data from the NHIC and HIRA. Accordingly, this study used additional data from the Korean Health Panel to compensate for these limitations. The Korea Health Panel survey was conducted through the collaboration of the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs and the NHIC in 2007 [9].

The estimated costs of disease were calculated in Korean won (WON) and converted into US dollars (US $) at a rate of US $1 = 1,104.76 WON based on data from the Korea Exchange Bank. This conversion represents the average exchange rate in 2008 [10].

This study measured the economic burden of RHD using a prevalence approach. The International Classification of Diseases, tenth version (ICD-10), designates “I01-I09” as the code for RHD. Accordingly, we requested insurance claims data about “I01-I09” from the National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC), including prevalence of cases and costs of medical services for outpatients and inpatients in 2008.

We calculated how many subjects among that same sample sought medical care for RHD during 2008. In turn, the economic burden of RHD was calculated by summing medical costs for inpatients and outpatients in 2008. In the case of outpatients, because of the possibility of overuse or errors, we defined patients as those who visited an outpatient clinic due to RHD more than three times during 2008.

This study used the estimated mid-year population of 2008 from the National Statistical Office (NSO) to estimate the prevalence of the disease [11]. We divided subjects into three age groups (0–19 years, 20–59 years, and 60 years and older) and calculated the respective prevalences of RHD.

We separated direct costs and indirect costs when calculating the socioeconomic burden of the disease on patients (Fig. 1).

The direct costs of treating the disease included direct medical care costs as well as direct non-medical care costs. Direct medical care costs included expenses paid by insurers and patients, as well as the costs of non-covered care and pharmaceuticals.

To estimate the costs of non-covered care, we considered out-of-pocket expenses based on data about the ratio of non-covered care costs according to the NHIC (non-covered care cost ratio of RHD: inpatient, 32.8 %; outpatient, 9.7 %). Pharmaceutical costs were calculated based on drug fees from HIRA’s claims data about “I01-I09”.

m month; DHC direct healthcare cost; IC inpatient cost; NBRi non-covered rate of inpatient; IPC inpatient pharmaceutical cost; OC outpatient cost; NBRo non-covered rate of outpatient; OPC outpatient pharmaceutical cost; RC rehabilitation aid cost.

Direct non-medical costs included costs of transportation for hospital visits and caregiver expenses. We computed transportation costs by multiplying round-trip transportation costs by the number of hospitalizations and by the days spent visiting outpatient clinics, respectively, using NHIC data for 2008. Data from the Korean Health Panel of 2008 were used to determine round-trip transportation costs.

The average transportation cost per trip for inpatients on record in the Korea Health Panel was US $6.90, which included costs for both patients and caregivers, multiplied by two (round-trip). To calculate outpatient transportation costs, we assumed that US $0.70 was the average one-way fare to visit a clinic and multiplied US $0.70 by two to calculate the round-trip fare.

Traditionally in South Korea, patients are nursed by female relatives between 20 and 60 years of age. Therefore, we estimated total caregiver costs by multiplying the total days of hospitalization by $58.94, which was the average 2008 daily wage of women aged 20–59 years according to the Ministry of Employment and Labor [12]. To estimate costs for outpatients, we assumed that any outpatients aged 0–19 years or 60 years and older would be accompanied by caregivers. Accordingly, we used the 2008 price index to calculate the average daily wage per total visiting days in a method similar to that used for inpatient cases. We considered the time required to visit a clinic as one-third of the total typical working hours per day.

m month; NHC direct non-healthcare cost; TFi cost of one-way transportation fee for inpatients; Fi, ag frequency of inpatients per age group; TFo cost of one-way transportation for outpatients; Fo, ag frequency of outpatients per age group; WC wage of caregivers; I 2008/2005 price index of 2008 based on the data from 2005.

Indirect costs for patients included productivity loss costs and premature death costs and were calculated based on the human resource approach [13]. We multiplied the days of hospitalization for inpatients by an average wage per day to calculate the lost productivity. We assumed that patients who were 0–19 years of age, as well as patients who were 70 years and older, were not employed. Accordingly, costs due to lost productivity were calculated only for patients 20–69 years of age. Data from the Korean Ministry of Labor were used to estimate the average wage per day and average working hours according to age group [14]. The opportunity costs due to clinic visits were estimated by multiplying the average visiting hours by the number of visits. The average time required to visit outpatient clinics was estimated to be 3 hours. We defined 3 hours as one-third of the total working hours in a day and assumed that 3 hours included sufficient time for both the visit and travel to and from clinics [15].

The cost of premature death was estimated using data about causes of death reported by the Korean NSO. Future incomes were discounted by 0.03 per year to obtain a present value and were calculated until 65 years of age for each patient dying prematurely due to RHD.

m month; IDC indirect cost; AWag average wage of a certain age group; Fi, ag frequency of inpatients per age group; Fo, ag frequency of outpatients per age group; PAWag present value of average wage of a certain age group; Fd, ag frequency of death per age group.

Results

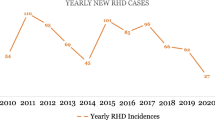

The overall prevalence of RHD was calculated as 220.50 of 100,000 people in 2008. The prevalence among males and females was determined to be 143.04 and 298.67 of 100,000 people, respectively. While females were 2.09 times more likely to suffer from RHD than males, it is noteworthy that there were no gender differences in the group of people 0–19 years of age, although there was a very large gender gap in people aged 20 years and older (Table 1).

The economic burden of RHD was estimated at US $67.25 million. Direct medical costs accounted for 54.32 % (US $36.53 million) of the total economic burden of RHD, while direct non-medical costs accounted for the lowest percentage of total expenses at 6.66 % (US $4.48 million). Total indirect costs were estimated to be US $26.26 million, occupying 39.05 % of the total economic burden of RHD. This study also revealed that direct costs and indirect costs were US $18.53 million and US $16.75 million, respectively, in patients from 20 to 59 years of age (Table 2).

Estimating the economic burden of disease from RHD based on gender determined that costs for females were about twice the costs for males. Specifically, costs were US $43.31 million for females and US $23.94 million for males (Table 2).

Analysis of the economic burden of disease due to RHD according to age showed that the burden was highest for people 20–59 years of age, at US $35.30 million. Individuals older than 60 years were more likely to suffer from RHD than individuals aged 20–59, but the total economic burden of RHD was higher for the group aged 20–59 because of the lower indirect costs for the 60 years and older group (Table 2). The economic burden of RHD per patient was US $700 for people aged 20–59 years. The economic burden per patient in this age group was higher than the average economic burden of RHD per patient (US $630) due to higher indirect costs for patients aged 20–59 years than for patients in other age groups (Table 3).

Discussion

This study estimates that the prevalence of RHD in Korea is 220.50 of 100,000 people. In particular, the prevalence of the disease among females is approximately twice as high as that in males. The prevalence of RHD in Korea is considerably high in comparison with the prevalence of RHD in other established market economy countries (i.e., approximately 30 cases of RHD per 100,000 people) [1]. In contrast, low-income countries have shown high prevalence of the disease due to risk factors of RHD that include low economic status, overcrowding, poor hygiene, low academic standards, and limited access to medical facilities. Particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, RHD prevalence has been calculated at approximately 350 cases per 100,000 people [3, 16, 17].

Most remarkably, the prevalence of RHD in Korea is concentrated among people of old age. According to one study, high-income countries show a high prevalence due to the increasing age of society, while RHD prevalence among young children and adults is high in low-income countries [18]. Based on the results of the current study, the prevalence of RHD in Korean people aged 60 years and older is the highest, at 791.07 of 100,000 people (51.88 % of the overall prevalence). Therefore, the prevalence pattern of RHD in South Korea is similar to that of high-income countries.

These results suggest that early detection of the disease is difficult because of certain characteristics of the disease. A previous study of RHD reported that most patients have no or only weak symptoms in the early stages of the disease. Furthermore, most diagnoses are made only after the disease has progressed considerably [19]. Therefore, interventions intended to reduce the prevalence of RHD in South Korea should target the elderly.

A survey of death rates from cardiovascular disease in Australia, which was based on data collected from 1987 to 2006, showed that, even though the total deaths from RHD had decreased during those past 20 years, the rate of deaths among females in the group of people aged 80 years and over had increased by approximately 5 % [1]. In addition, according to a recent survey conducted in the United States (US), the economic burden of RHD is expected to more than double over the next 20 years [18]. As the baby boom generation ages, it is predicted that the economic burden of disease among people of old age will increase more and more. Therefore, RHD diagnosis, treatment, and prevention need to be considered critical aspects of public health policies in high-income countries with aging populations. South Korea is no exception. A survey targeting countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) showed that even though only 7.1 % of the population in South Korea was older than 65 years of age in 2007, the Korean population was aging at a faster rate than all the other countries except for Japan [20]. Since the economic burden of RHD in Korea is increasing due to aging, public health policies must establish countermeasures to prevent RHD, including methods of early diagnosis and treatment. Disease awareness education is also required to improve sanitary conditions for lower socioeconomic classes. In addition, the correct diagnosis and prompt treatment of disease should be facilitated among low-income groups by improving access to appropriate medical services.

In other studies associated with RHD, the prevalence of RHD in females is nearly double the disease prevalence in males, and the current study shows similar results. Because it was observed in female subjects over 20 years, this phenomenon is explained by several hypotheses. First, we considered undiagnosed RHD. Women with early RHD report no or only mild symptoms, and RHD is often not diagnosed until the sudden hemodynamic changes of pregnancy make the symptoms of RHD more apparent [21].

Furthermore, disease treatment is limited by restricted access to medical services. According to the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 27.3 % of women in 2008 were unable to visit hospitals when necessary, while only 18.2 % of males were unable to visit hospitals as needed [22]. The survey also showed that the denial of access to medical institutions increased by 9.9 % for females (the increase for males was 2.9 %) after calculating the rate of change from 2005 to 2008. These differences in access to medical services due to sex may be obstacles to early diagnosis and treatment of RHD.

This study estimates that the total cost of illness associated with RHD in South Korea is US $67.25 million per annum. According to age, the costs incurred in people aged 20–59 years and more than 60 years were US $35.30 million and US $31.63 million, respectively.

According to the results of a study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) related to rheumatic fever and heart disease, the economic burden of RHD was estimated to be US $40,920 using primary prevention alone, US $12,750 using tertiary prevention strategies (including cardiac surgeries), and US$ 5,520 using secondary prevention [23]. In New Zealand, the management of chronic RHD alone may cost as much as 71 % of the total national allocation for treating rheumatic fever and heart disease. Much of this expenditure could be prevented via vigorous efforts to develop less expensive secondary prevention programs, such as early detection via echocardiography and early treatment with antibiotics [23]. Since this disease is difficult to detect in its early stages, investment in secondary prevention is more cost-effective than primary and tertiary prophylaxis [23]. Prevention can further relieve the economic burden of RHD by vitalizing early diagnosis through primary medical systems to reduce costs of hospital treatment and rates of operation [24, 25]. Secondary prevention also requires a registration system to efficiently manage patients who have been diagnosed early. If secondary prevention is strategically implemented by initiating registration programs for patients with rheumatic fever and heart disease in order to provide them with proper precautions and treatments, then efficiency can be maximized [26, 27].

This study has a number of limitations. Because this study is based on insurance claims data, it was not possible to calculate the distribution of disease based on accessibility according to geographic or economic differences among patients. This study would offer more practical evidence for effective disease prevention strategies with a comparison of disease patterns among patients according to urban or rural residence and differing income brackets, which was not possible given the data available. In addition, this study assumed that costs due to premature death and productivity loss did not occur among patients aged 70 years or older, but the results could change with different assumptions.

Conclusion

This study estimates that the overall prevalence of RHD is 220.50 cases of disease out of 100,000 people. The economic burden due to RHD in Korea was calculated at US $67.25 million in 2008. Specifically, the cost for patients older than 60 years comprised 47.03 % of this total (US $31.63). The increasing number of elderly people in Korea contributes to the increasing expansion of the economic burden of RHD. Since early diagnosis and treatment are important to prevent RHD, public health policies that emphasize secondary prophylaxis must be promoted along with primary and tertiary prevention strategies.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2010) Cardiovascular disease mortality: trends at different ages. Cardiovascular series no. 31. Cat. no. 47. AIHW, Canberra

Carapetis JR, Currie BJ, Mathews JD (2000) Cumulative incidence of rheumatic fever in an endemic region: a guide to the susceptibility of the population? Epidemiol Infect 124:239–244

Steer AC, Carapetis JR, Nolan TM, Shann F (2002) Systematic review of rheumatic heart disease prevalence in children in developing countries: the role of environmental factors. J Paediatr Child Health 38:229–234

Lucas G, Triborilloy C (2000) Epidemiology and etiology of acquired heart valve diseases in adults. Rev Prat 50:1642–1645

Soler–Soler J, Galve E (2000) Worldwide perspective of valve disease. Heart 83:721–725

Lee SY, Chun CB, Lee YG, Seo NK (2008) The National Health Insurance system as one type of new typology: the case of South Korea and Taiwan. Health Policy 85:105–113

Kang HY, Yang KH, Kim YN, Moon SH, Choi WJ, Kang DR, Park SE (2010) Incidence and mortality of hip fracture among the elderly population in South Korea: a population-based study using the national health insurance claims data. BMC Public Health 10:230

Health Insurance Review and Assessment service [http://www.hira.or.kr/rb/rbb_english/index.html]. Accessed Oct 2011

Korea Health Panel [http://www.khp.re.kr/English/about_01.jsp]. Accessed Oct 2011

Korea Exchange Bank [http://www.keb.co.kr/] (in Korean). Accessed Oct 2011

Population projections for Korea [http://kostat.go.kr/wnsearch/search.jsp] (in Korean). Accessed Oct 2011

Ministry of Employment and Labor [http://laborstat.molab.go.kr/] (in Korean). Accessed Oct 2011

Drummond MF, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW (1997) Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ministry of Employment and Labor. Survey Report on Labor Conditions by Employment type in 2008. Available online at www.laborstat.molab.go.kr. Accessed Oct 2011

Oh IH, Yoon SJ, Seo HY, Kim EJ, Kim YA (2011) The economic burden of musculoskeletal disease in Korea: a cross sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12:157

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2004) Heart, stroke and vascular diseases, Australian facts 2004. Cardiovascular disease series no. 22. Cat. No. CVD 27. AIHW AND National Heart Foundation of Australia, Canberra

Jonathan RC, Andrew CS, Mulholland EK, Weber M (2005) The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 5:685–694

Vuyisile TN, Julius MG, Thomas NS, John SG, Christopher GS, Maurice ES (2006) Burden of valvular heart disease: a population-based study. Lancet 368:1005–1011

Walsh WF (2010) Medical management of chronic rheumatic heart disease. Heart Lung Circ 19:289–294

OECD Health Data, 2009. OECD. Paris. [www.oecd.org/health/healthdata]

National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (Chronic Heart Failure Guidelines Expert Writing Panel) Guidelines for the prevention, detection and management of chronic heart failure in Australia (2006) National Heart Foundation of Australia

Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/intro/intro03.jsp] (in Korean)

Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organization, Geneva (2004) (Technical Report Series No. 923)

Rizvi SF, Khan MA, Kundi A, Marsh DR, Samad A, Pasha O (2004) Status of rheumatic heart disease in rural Pakistan. Heart 90:394–399

The WHO Global Programme for the prevention of RF/RHE (2000) Report of a consultation to review progress and develop future activities. Geneva, World Health Organization (document WHO/CVD/OO.1)

Tibazarwa KB, Volmink JA, Mayosi BM (2008) Incidence of acute rheumatic fever in the world: a systematic review of population-based studies. Heart 94:1534–1540

Samanatha MC, Janathan RC, Joseph HK, Andrew CS (2009) Rheumatic heart disease and its control in the Pacific. Cardiovasc Ther 7(12):1517–1524

Acknowledgments

This study was part of the research program (to measure the economic burden of cardio-cerebrovascular disease in Korea, application R1006511), financed by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In addition, the study used data from the Korea Health Panel, with access made possible by the assistance of Dr. Jung Young Ho, whose assistance we greatly appreciate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, HY., Yoon, SJ., Kim, EJ. et al. The economic burden of rheumatic heart disease in South Korea. Rheumatol Int 33, 1505–1510 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-012-2554-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-012-2554-6