Abstract

Maternal effects mediated by nutrients or specific endocrine states of the mother can affect infant development. Specifically, pre- and postnatal maternal stress associated with elevated glucocorticoid (GC) output is known to influence the phenotype of the offspring, including their physical and behavioral development. These developmental processes, however, remain relatively poorly studied in wild vertebrates, including primates with their relatively slow life histories. Here, we investigated the effects of maternal stress, assessed by fecal glucocorticoid output, on infant development in wild Verreaux’s sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi), a group-living Malagasy primate. In a first step, we investigated factors predicting maternal fecal glucocorticoid metabolite (fGCM) concentrations, how they impact infants’ physical and behavioral development during the first 6 months of postnatal life as well as early survival during the first 1.5 years of postnatal life. We collected fecal samples of mothers for hormone assays and behavioral data of 12 infants from two birth cohorts, for which we also assessed growth rates. Maternal fGCM concentrations were higher during the late prenatal but lower during the postnatal period compared to the early/mid prenatal period and were higher during periods of low rainfall. Infants of mothers with higher prenatal fGCM concentrations exhibited faster growth rates and were more explorative in terms of independent foraging and play. Infants of mothers with high pre- and postnatal fGCM concentrations were carried less and spent more time in nipple contact. Time mothers spent carrying infants predicted infant survival: infants that were more carried had lower survival, suggesting that they were likely in poorer condition and had to be cared for longer. Thus, the physical and behavioral development of these young primates were impacted by variation in maternal fGCM concentrations during the first 6 months of their lives, presumably as an adaptive response to living in a highly seasonal, but unpredictable environment.

Significance statement

The early development of infants can be impacted by variation in maternal condition. These maternal effects can be mediated by maternal stress (glucocorticoid hormones) and are known to have downstream consequences for behavior, physiology, survival, and reproductive success well into adulthood. However, the direction of the effects of maternal physiological GC output on offspring development is highly variable, even within the same species. We contribute comparative data on maternal stress effects on infant development in a Critically Endangered primate from Madagascar. We describe variation in maternal glucocorticoid output as a function of ecological and reproductive factors and show that patterns of infant growth, behavioral development, and early survival are predicted by maternal glucocorticoids. Our study demonstrates how mothers can influence offspring fitness in response to challenging environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The survival and reproductive success of animals are determined by adequate responses to challenges and opportunities in their physical and social environments (Alberts 2019). These responses are modulated by phenotypic differences among individuals, which in turn are shaped during development by additive genetic and maternal effects (Moore et al. 2019). While these developmental processes remain relatively poorly studied in wild vertebrate populations, it has been established that maternal effects are mediated by nutrients or specific endocrine states of the mother that affect offspring morphology, but also life history traits and behavior, and that they tend to influence juvenile traits more than adult traits (Bernardo 1996; Moore et al. 2019; Mouton and Duckworth 2021). In addition, it is now widely recognized that events experienced by individuals during early development and adolescence not only have instantaneous fitness effects, but that they can also have downstream consequences for behavior, physiology, survival, and reproductive success well into adulthood, in taxa ranging from insects to humans (Patin et al. 2002; Lea et al. 2015; Tung et al. 2016; Morimoto et al. 2017; Langenhof and Komdeur 2018; Sachser et al. 2018; Schülke et al. 2019; Rosenbaum et al. 2020; Snyder-Mackler et al. 2020; Thompson and Cords 2020; Weibel et al. 2020). In fact, the environment individuals experience during early development can even impact the phenotypes and fitness of their own later offspring (Zipple et al. 2019, 2021).

Ultimate explanations for maternal effects focus on phenotypic adaptations to environmental factors, either instantly or in the future, but the effects themselves may also result from intrinsic factors, such as maternal age (Monaghan 2008). These effects are based on the fact that, as a consequence of anisogamy, female fitness is primarily limited by mothers’ ability to provide pre- and postnatal maternal investment, which, in the end, is linked to maternal condition and access to resources. If a mother is exposed to favorable environmental conditions (e.g., in terms of climate, food, predators, or parasite exposure), and if these conditions are stable and predictable, her offspring should enjoy relatively high fitness under similarly good conditions. However, if the environmental conditions are more variable and less predictable, there is a risk of a mismatch between the maternal environment and that of her then adult young (Nettle and Bateson 2015). If offspring that developed under good conditions achieve the highest fitness regardless of future environmental conditions, they enjoy a so-called silver-spoon effect (Grafen 1988). If maternal effects adapt offspring to the expected future environmental conditions, they exhibit an external predictive adaptive response (PAR). When infants develop instead under developmental constraints that affect their somatic state negatively, and they adjust to this unfavorable internal state (e.g., by accelerating reproduction), regardless of future environmental conditions, this represents an internal PAR (Gluckman et al. 2005; Sheriff and Love 2013; Hanson and Gluckman 2014; Schülke et al. 2019). Because the predictability of later-life environments decreases with increasing longevity, external PARs are not expected in long-lived species (Wells 2007a), such as most primates (van Noordwijk 2012; van Noordwijk et al. 2013; Berghänel et al. 2016; Snyder-Mackler et al. 2020). Here, an alternative model has been proposed, postulating that early-life effects promote immediate survival, independent of any costs this may incur later in life (Lea et al. 2015, 2018), though these costs may be partly compensated for by internal PARs (Nettle et al. 2013).

In addition to ecological crises, infants may experience stressful social events, like weaning-related rejection, maternal death, or birth of a sibling (Tung et al. 2016; Maestripieri 2018), or they are impacted by maternal senescence (Ivimey-Cook and Moorad 2020), all of which tend to reduce the amount of maternal investment they receive. There is empirical evidence from studies of both humans and other vertebrates for rippling effects of early life adversity on offspring development and fitness (Lummaa and Clutton-Brock 2002; Weinstock 2008; Giesing et al. 2011; Berghänel et al. 2017; Crockford et al. 2020; McGhee et al. 2021), but the proximate mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain poorly known, especially in wild animals (Edes and Crews 2017; Langenhof and Komdeur 2018; Lea et al. 2018; Hawkley and Capitanio 2020). However, one factor that has been identified as important mediator of the relationship between individuals’ early experiences and health outcomes in several species and taxa is the exposure to maternal stress hormones, i.e., glucocorticoids (GC; Love et al. 2013), both pre- and postnatally.

In birds and other oviparous species, mothers can adjust offspring´s exposure to prenatal GC levels only during egg production (Love and Williams 2008). In mammals, however, maternal GCs are transferred through the placenta and later on through mother's milk and can therefore presumably be fine-tuned over longer periods of early offspring development (Hinde 2013). Maternal GC levels in free-living birds and mammals are predictably increased in response to unpredictable changes in food availability or quality (Love et al. 2005; Welcker et al. 2009), but also to other potential stressors, like reproduction or predation risk, that make an increase in mobilized energy beneficial (Beehner and Bergman 2017). Pre-, and in the case of mammals, also postnatal maternal stress is known to influence several aspects of offspring’s phenotype, including their physical development (Berghänel et al. 2017), behavioral development (Maestripieri 2018), skill acquisition (Berghänel et al. 2015), or immune function (Veru et al. 2014). However, the direction of the effects of maternal physiological GC output on offspring development is highly variable, even within the same species (Hauser et al. 2007; Berghänel et al. 2017; Schülke et al. 2019; for intra-specific plasticity, see Dantzer et al. 2013), leading to opposite conclusions about their ultimate function.

Accordingly, the observed offspring phenotypic responses to maternal GCs have either been interpreted as unavoidable negative outcomes, such as reduced offspring size or growth (Love et al. 2013), or as evidence for adaptive maternal programming that prepares offspring for their predictable future environment (Sheriff et al. 2017), or as adjustments of their internal somatic state (Nettle et al. 2013). In addition, there is also evidence for sex-specific intraspecific variation in the response to maternal stress. For example, infant male and female rhesus monkeys exhibited different temperament responses to variation in maternal milk cortisol. Infant males of mothers with higher milk GC concentrations showed a more confident temperament (more active, playful, and curious), whereas female infants did not (Sullivan et al. 2011). Similarly, in humans, higher milk cortisol levels were found to induce “negative affectivity” (fear, sadness, frustration) in daughters but not in sons (Grey et al. 2013). Consequently, there is a need for studies contributing comparative information from additional taxa to document patterns and drivers of maternal stress effects on infant development.

Here, we contribute new data on the effects of maternal stress as well as environmental and social adversaries on infant development in wild Verreaux’s sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi), a group-living Critically Endangered (Louis et al. 2020) primate from the seasonal dry forests of southwestern Madagascar. Specifically, we first examine the effects of variation in local climate, food availability, and previous reproduction on maternal GCs. In a second step, we explore how maternal GC output is linked to the physical and behavioral development as well as to the survival of two cohorts of infants.

Previous studies have explored the effects of environmental stressors on individual stress hormone levels in various lemur species (Lemuriformes). In both lemurids (Lemuridae) and indrids (Indriidae), GC output is influenced by seasonal variation, and average levels are higher during the dry season in Verreaux’s sifakas (Rudolph et al. 2019) and ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta, Cavigelli 1999; Pride 2005). In ring-tailed lemurs, GCs are elevated during droughts and cyclones (Fardi et al. 2018). GCs were also found to be higher during periods of low food availability, especially during fruit scarcity, in collared lemurs (Eulemur collaris, Balestri et al. 2014), red-bellied lemurs (E. rubriventer, Tecot 2008; 2013), ring-tailed lemurs (Pride 2005), diademed sifakas (P. diadema, Tecot et al. 2019), and in Verreaux’s sifakas (Rudolph et al. 2020).

Moreover, social variables were also found to induce changes in GC levels, albeit not consistently so. For example, members of larger groups exhibited elevated GC level in ring-tailed lemurs (Pride 2005; Fardi et al. 2018; Gabriel et al. 2018), but not in Verreaux’s sifakas (Rudolph et al. 2019). Moreover, increased GC levels characterized top-ranking females in ring-tailed lemurs (Cavigelli 1999; Cavigelli et al. 2003) and dominant males in Verreaux’s sifakas (Fichtel et al. 2007; Rudolph et al. 2020), but rank did not predict GC levels in male red-fronted lemurs (Ostner et al. 2008) and male ring-tailed lemurs (Gould et al. 2005). Further, fluctuations in group aggression rates associated with seasonal reproduction did not influence GC levels in male ring-tailed lemurs (Gould et al. 2005), but increases in male GC levels during the mating and/or birth season were reported for Verreaux’s sifakas (Fichtel et al. 2007; Brockman et al. 2009; Rudolph et al. 2020), red-fronted lemurs (Ostner et al. 2008), and collared lemurs (Balestri et al. 2014). Finally, GC levels increased during late gestation and the birth season in female sifakas (Tecot et al. 2019; Ross 2020; Rudolph et al. 2020), collared (Balestri et al. 2014), and ring-tailed lemurs (Cavigelli 1999). Thus, lemurs apparently respond to challenging ecological and social factors with changes in GC levels, and some of these responses appear to be variable among species and between the sexes. Previous lemur studies have not linked these stress responses to infant development, however, even though this variability in GC responsiveness offers a promising opportunity for examining whether pre- and postnatal maternal GC output affects infant development and if so, in which way.

Here, we predicted that relatively harsh climatic conditions (i.e., low temperatures and rainfall) with low food availability will increase maternal average GC levels, both prenatally and postnatally. Further, focusing on developmental constraints, we predicted that elevated pre- and postnatal maternal GC concentrations will be associated with reduced maternal investment (e.g., in terms of infant carrying) and retarded infant physical and behavioral development (but see Dantzer et al. 2013). Specifically, we predicted that, as in some other species (Sullivan et al. 2011; Grey et al. 2013), infants from mothers with higher GCs will grow and develop more slowly and exhibit reduced levels of playing, foraging, locomotion, and grooming compared to mothers exhibiting lower GC concentrations. Finally, given the detrimental effects of prolonged exposure to high GC levels in adult primates (Campos et al. 2021), we predicted that high maternal GC levels are also associated with an increased mortality risk for infants.

Methods

Study site and subjects

Data on wild Verreaux’s sifaka were collected during two successive breeding seasons (2017 and 2018) at the field station of the German Primate Center at Kirindy Forest/CNFEREF, located in central western Madagascar (Kappeler and Fichtel 2012). The area is dominated by dry deciduous forest and a climate characterized by a hot wet season from November to March and a cool dry season from April to October. A local population of Verreaux’s sifakas has been studied in Kirindy Forest since 1995. These lemurs are habituated to human observers and are being individually marked with unique neck collars when they are about 8 months old or when they immigrate into the study population.

Verreaux’s sifakas are 3 kg arboreal, foli-frugivorous primates that can live up to 30 years (Richard et al. 2002). They live in groups of about 6 individuals, and there is no sexual size dimorphism (Lawler 2009; Kappeler and Fichtel 2012). Females become mature at 5 years and give birth to a single infant at the height of the austral winter (July to August) after a gestation period of about 5 months. Weaning takes place at the height of the wet season (January to February), when food is most abundant. Infants are entirely dependent on their mother during their first 3 months of life (Jolly 1966), and mothers constitute their primary caregiver and invest more in transport than the other group members (Patel 2007; Malalaharivony et al. 2021). Infant mortality is very high, with about 62% of infants dying during their first year of life (Kappeler and Fichtel 2012).

Behavioral and morphometric data

A total of 12 infants, whose exact birth dates were known from daily group censuses, and their mothers from 7 study groups served as focal animals. All of the mothers included in this study were multiparous, and four of them had an infant in both study years. Infants were born between July and August, with most being born in July. We observed infants until February for the first cohort (N = 6 infants, 2017) and until December for the second cohort (N = 6 infants, 2018). An effort was made to record the behavior of mothers and infants simultaneously for 5 daily observation hours, balanced between 3 h in the morning (8:00–11:00 h) and 2 h in the afternoon (14:00–16:00 h), using continuous focal animal sampling (Altmann 1974). Focal subjects were chosen in a randomized but counter-balanced manner throughout morning and afternoon observations. As our study involved focal animal observations, it was not possible to record data blind.

Operational definitions of all recorded behavioral elements are provided in SEM Table 1 (see also Malalaharivony et al. 2021). To quantify patterns of infant development, we specifically recorded the occurrence and duration of all infant activities, such as feeding on solid food and the time spent in nipple contact, which provides a proxy for the opportunity to obtain access to milk, solitary locomotor, and object play as well as independent locomotion. We also recorded all interactions, including social play and grooming with other group members to characterize the social development of infants. Finally, to assess maternal investment, we recorded the proportion of time infants were carried by their mothers.

We used two independent methods to assess infant physical growth rates. One non-invasive estimate was based on changes in infants’ lower arm length, which was estimated once a month via photogrammetry (Breuer et al. 2007). A second estimate was based on records of body mass obtained during infants’ first capture when they were about 9 months old and related to this species’ estimated mass at birth (Kappeler and Fichtel 2012). Two infants died postnatally before either estimate could be obtained. Both measures were positively correlated with each other and described and discussed in detail elsewhere (Malalaharivony et al. 2021).

Phenology and climatic variables

Food availability, estimated as the relative abundance of leaves, flowers, and fruits (i.e., the main constituents of sifakas’ diet, Guevara et al. 2021), was assessed during bi-weekly phenology transects of 784 trees in the study area as detailed elsewhere (Koch et al. 2017). Briefly, we applied a semi-quantitative method in which the availability for each food item was scored on an ordinal scale ranging from 0 to 4, where 0 reflects the complete absence of the item and 4 represents its maximum abundance. Average monthly scores for leaves, fruits, and flowers were summed up to obtain one score for food availability per month. A fully automatic weather station (Lamprecht, Göttingen, Germany) recorded data on ambient temperature and rainfall at the field station.

Collection of fecal samples and GC analyses

We attempted to collect weekly fecal samples for glucocorticoid metabolite (fGCM) analyses from mothers (N = 377) throughout gestation and lactation (SEM Table 2). Samples uncontaminated with urine were collected immediately after defecation in the morning between 07:00 and 11:00 h and transferred into a 15-ml tube containing 5 ml of 80% ethanol in water. FGCM extractions took place in our field laboratory using a validated field extraction method (Shutt et al., 2012) applied successfully in several other studies on wild primates (Rimbach et al. 2013; Hämäläinen et al. 2015; Kalbitzer et al. 2015), including Verreaux´s sifakas (Rudolph et al., 2019). In brief, samples were manually homogenized in their original ethanolic solvent, subsequently vortexed, and then centrifuged manually (Rudolph et al., 2019). About 1.5 ml of the supernatant were finally decanted into 2-ml polypropylene safe-lock tubes (Eppendorf®, Hamburg, Germany) for storage at ambient temperatures in the dark. Within 1–6 months following sample collection, fecal extracts were shipped to the German Primate Center and stored at − 20 °C until fGCM analysis.

We assessed fGCM concentrations by using a validated enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for the measurement of immunoreactive 11ß-hydroxyetiocholanolone, which is a group-specific measure of 5ß-reduced cortisol metabolites that has been shown to reliably track adrenocortical activity from fecal samples in several primate and other mammal species (Braga Goncalves et al. 2016; Heistermann et al. 2006), including Verreaux’s sifakas (Fichtel et al. 2007; Rudolph et al. 2019, 2020). For details of assay methodology, see Heistermann et al. (2006). Inter-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) of high- and low-value quality controls were 11.2% (high) and 9.5% (low), while both intra-assay CVs were < 10%. All hormone concentrations are expressed as ng/g wet weight of feces.

Statistical analyses

In general, we fitted statistical models (LMM, GlmmTMB) in R (version 4.0.3; R Core Team 2018). All covariates in the models were z-transformed in order to obtain models that are easier to interpret (Schielzeth 2010) and to facilitate model convergence. For LMMs, we checked the assumptions of normality distributions and homogeneity by visual inspection of a QQ-plot (Field 2009) of residuals and residuals plotted against fitted values (Queen et al. 2002). For GlmmTMBs, we checked for overdispersion. For both types of models, we assessed model stability through the level of estimated coefficients and standard deviations (Nieuwenhuis et al. 2012). Furthermore, we checked collinearity issues by deriving variance inflation factors (VIF; Field 2009) of the standard linear model lacking the random effects. To test the significance of the predictors as a whole, we compared the fit of the full model with that of the null model comprising the intercept and the random effects (Forstmeier and Schielzeth 2011). Statistics for these comparisons are given in the summary tables of the respective models.

According to when fecal samples were collected, we categorized log-transformed fGCM concentrations into a pre- or postnatal period. For analyses examining the effects of maternal fGCM levels on infant development, the 6 months of the prenatal period were further divided into three periods between the estimated date of conception (calculated back from the birth date of the infant) and the date of birth because maternal GCs are known to increase during late gestation (Rudolph et al. 2019), presumably also because of increasing fetal GC production (see below). We therefore distinguished between the early-mid prenatal period, which lasted from February to May, and the late prenatal period, which included data from June and July. The postnatal period was defined as the period between the birth date and the end of data collection, spanning the months from July/August to December for most infants of both birth cohorts.

Predictors of variation in fGCM concentrations and influence of FGCMs on maternal care

To assess variation in pre- and postnatal fGCM concentrations, we fitted a Linear Mixed Model using the package lme4 (Bates et al. 2014). Since one infant died on day 1 postnatally, we excluded postnatal samples collected from this female, resulting in a sample size of N = 359. We fitted log-fGCM concentrations as response, period (early/mid, late prenatal and postnatal), monthly cumulative rainfall, cumulative rainfall during the preceding wet season until tentative conception (November to January), and mother’s age (in years) as fixed factors. Mothers’ identity was included as a random factor, and all mothers were either the only or the dominant adult female of their group. We included rainfall as a proxy for food availability in this model because fruit availability, which is associated with variation in fGCM concentrations (Rudolph et al. 2020), was colinear with increases in fGCM concentrations during early pregnancy. To avoid overconfident model estimates and to keep type I error rate at the nominal level of 0.05, we included random slopes (Schielzeth and Forstmeier 2009; Barr et al. 2013) of mother’s age, rainfall before conception, and rainfall within mothers’ identity. Originally, we also included parameters for the correlations between random slopes and intercepts, but as the model did not converge, we had to exclude them again.

To examine whether maternal prenatal fGCM concentrations predict postnatal fGCM concentrations, we fitted another LMM. As response we fitted postnatal fGCM concentrations, average prenatal fGCM concentrations as fixed factor and mother’s identity as random factor. To control for autocorrelation, we fitted two additional models, using the package “nlme” (Pinheiro and Bates 2000), by including sample date as correlation. Samples that were collected on the same day (N = 18) were excluded in these models. Since the results did not deviate between these and the original models without controlling for autocorrelation, we present the original models and depict the results of the new models in the SEM (Table S3, S4).

To quantify inter-individual variation in maternal care, we calculated the proportion of time (minutes per hour) for each behavioral activity based on observational data collected between July and December of each study year. To estimate variation in the proportion of time mothers spent carrying infants, we fitted a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM; Baayen 2008) with a beta error distribution and logit link function (package glmmTMB; McCullagh and Nelder 1989; Bolker 2008). The proportion of time mothers spent carrying infants was fitted as response, and infants’ age in weeks, infant’s sex, average early/mid prenatal and monthly postnatal fGCM concentrations, study year, fruit availability, and mother’s age as fixed factors. Individual and maternal identities were fitted as random factors, including monthly postnatal fGCM concentrations and mothers’ age within maternal identity and fruit availability as well as monthly postnatal fGCM concentrations within individual identity as random slopes. Originally, we also included parameters for the correlations between random slopes and intercepts, but as the model did not converge, we had to exclude them again.

Influence of maternal fGCM concentrations on infant physical and behavioral development

To estimate the influence of maternal early/mid prenatal and postnatal fGCM concentrations on infants’ body mass and arm length growth rates, we calculated the mean maternal pre- and postnatal fGCM concentrations and correlated them with individual growth rates derived from a generalized least square regression (Malalaharivony et al. 2021) by using Spearman rank correlations.

To estimate variation in infant behavioral development (proportion of time spent in nipple contact, foraging, and playing), we fitted three Generalized Linear Models (GLMM; Baayen et al. 2008) with a beta error distribution and logit link function (package glmmTMB; McCullagh and Nelder 1989; Bolker 2008). The proportion of time spent in nipple contact, foraging, or playing per observation hour was fitted as response, and infants´ age in weeks, average early/mid prenatal and monthly postnatal fGCM concentrations, study year, fruit availability, and mother’s age were included as fixed factors. For the model investigating variation in time spent playing, we included another fixed factor differentiating between play types (solitary locomotor, solitary object, and social play). In the models fitting the time spent in nipple contact and foraging, individual and maternal identities were fitted as random factors including mother’s age and fruit availability within mother’s identity and postnatal fGCM concentrations and fruit availability as random slopes within individual identity without correlations between random slopes and intercepts. In the model fitting time spent playing, we had to exclude the random slope of mother’s age with mother’s identity because the model did not converge.

The sample sizes for the proportion of time infants spent grooming or locomoting independently were relatively small because these behaviors were more regularly shown towards the end of the study period when infants were older. We therefore calculated the mean of the time spent grooming or locomoting independently and correlated them with mean average early/mid prenatal and postnatal fGCM concentrations by using Spearman rank correlations.

To assess factors predicting infants’ survival during the first 1.5 years, we calculated Cox proportional-hazards model (function “Coxph,” “survival” package; Therneau et al. 2020) with the function Surv (age at 30.01.2020 | survived 1.5 years) as proportional hazard. One infant died a day after birth, which was excluded in these analyses. All other infants (n = 5) died after the end observation period at a mean age of 11.8 ± SD 4.4 months. Since some mothers gave birth in both years, we included maternal identity as a cluster to control for repeated measures. As predictors, we included average early/mid prenatal and postnatal fGCM concentrations, time being carried by the mother, body mass and arm length growth rates, time spent in nipple contact and foraging, and year of the birth cohort. Because of the small sample size of 12 infants, we fitted a separate model for each predictor variable.

Results

Predictors of variation in prenatal fGCM concentrations and influence of fGCM levels on maternal care

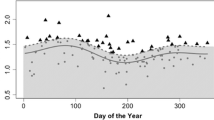

FGCM concentrations differed across periods, with higher levels during the late prenatal period in comparison to the early/mid prenatal period. (Table 1, S3, Fig. 1a). Average postnatal fGCM concentrations were lower than early/mid concentrations, though absolute values appeared to be in between early/mid fGCM concentrations. Rainfall was negatively correlated with fGCM concentrations, with females having higher fGCM concentrations during periods with little rainfall (SEM, Fig. S1). Mothers that had given birth to an infant the year before experienced higher average fGCM concentrations (Fig. 1b). Rainfall during the wet season before conception and mother’s age did not co-vary with fGCM concentrations (Table 1, S3). Since rainfall is a proxy for food availability (Rudolph et al. 2020), food shortages might have resulted in reduced maternal condition and were associated with higher stress. Prenatal fGCM concentrations predicted postnatal fGCM concentrations (LMM: N = 194, likelihood ratio test comparing the full with the null model: χ2 = 7.61, df = 1, p = 0.006; estimate = 0.28, SE = 0.09, p = 0.016, Table S4).

Variation in fGCM concentrations across a the early/mid prenatal (light green), late prenatal (dark green) and postnatal period (beige) in Verreaux’s sifaka mothers. b Comparison of fGCM levels between mothers that gave birth to an infant in the previous year or not. Depicted are boxplots showing medians (solid lines), inter-quartile ranges (boxes), ranges (whiskers) and outliers (> 1.5 x IQR; open circles) of fGCM concentrations. Note that the y-axis is depicted on a log scale but axis tick labels show the original fGCM values

The time spent carrying infants decreased with infants’ age (Table 2). Both, early/mid and postnatal fGCM concentrations, predicted carrying time, with mothers having lower fGCM concentrations spending more time carrying their infants (Figs. 2a, b and 3). Fruit availability, birth cohort, and mother’s age did not influence the time spent carrying infants (Table 2).

Influence of maternal fGCM concentrations on infant physical and behavioral development

Neither early/mid prenatal nor postnatal fGCM concentrations correlated with average body mass growth rates (Spearman rank correlation: early/mid prenatal, N = 10, r = 0.51, p = 0.137; postnatal, N = 10, r = 0.61, p = 0.062). Similarly, arm length growth rates did not correlate with early/mid or postnatal fGCM concentrations (Spearman rank correlation: early/mid prenatal, N = 10, r = 0.25, p = 0.492; postnatal, N = 10, r = 0.37, p = 0.296). However, average prenatal fGCM concentrations correlated positively with both growth rates (Spearman rank correlation: body mass growth rate, N = 10, r = 0.74, p = 0.014; arm-length growth rate, N = 10, r = 0.66, p = 0.044, SEM Fig. S2, S3).

Postnatal fGCM concentrations and fruit availability predicted the time spent in nipple contact (Table 3). Infants of mothers with higher postnatal fGCM concentrations spent more time in nipple contact. In addition, infants spent more time in nipple contact when more fruits were available. Neither infant’s nor mother’s age, sex, birth cohort, or early/mid prenatal fGCM concentrations co-varied with time spent in nipple contact (Table 3).

Infants spent more time foraging with increasing age. Early to mid fGCM concentrations predicted the proportion of time infants spent foraging; infants of mothers with higher fGCM concentrations spent more time foraging (Fig. 4, Table 4). Postnatal fGCM concentrations, birth cohort, mother’s age, and fruit availability did not co-vary with time spent foraging (Table 4).

The time infants spent playing increased with age, and they spent more time with solitary locomotor than with solitary object or social play (Fig. 5, Table 5). Early/mid prenatal fGCM concentrations predicted time infants spent playing, with infants of mothers exhibiting higher prenatal fGCM concentrations spending more time playing (Fig. 5). Infants of the birth cohort 2018 spent more time playing than infants of the birth cohort 2017, but postnatal fGCM concentrations, fruit availability, and mother’s age did not predict the time infants spent playing (Table 5).

Proportion of time (m/hr) infants spent playing (gray = solitary locomotor play, blue = solitary object play, red = social play) as a function of maternal prenatal fGCM concentrations. Dashed line indicates the regression line. Note that the x-axis is depicted on a log scale, but axis tick labels show the original fGCM values

The average proportion of time infants spent locomoting independently did neither correlate with early/mid prenatal nor postnatal fGCM concentrations (Spearman rank correlation, early/mid prenatal fGCM, N = 7, r = 0.07, p = 0.906; postnatal fGCM, N = 7, r = 0, p = 1). Similarly, the average proportion of time infants spent grooming did not correlate with either maternal pre- or postnatal fGCM concentrations (Spearman rank correlation, prenatal fGCM, N = 11, r = 0.36, p = 0.313; postnatal fGCM, N = 10, r = 0.22, p = 0.537).

Infant survival was neither predicted by mid-early prenatal nor postnatal fGCM concentrations, but by the proportion of time being carried by the mother and arm length growth rate. Infants that were carried more often died earlier (Fig. 6; Table 6). In addition, infants with higher arm length growth rates lived longer, but body mass growth rate did not predict survival. Mother’s age, year of the birth cohort, and time spent foraging by the infants or being in nipple contact did not predict their survival either (Table 6).

Kaplan–Meier survival curve. Survival probability for infants surviving during the first 1.5 years depending on the time mother’s spent carrying infants (N = 6 infants surviving and N = 6 infants that died). For illustrative purposes, we divided the time spent carrying into much carrying (black line; above median time spent carrying and low (red line); below median time spent carrying)

Discussion

In this study, we investigated factors predicting maternal fGCM concentrations and their impact on infant physical and behavioral development in a wild population of Verreaux’s sifakas. We found that maternal fGCM concentrations were higher in the late prenatal period, compared to the early/mid prenatal period. Average postnatal fGCM concentrations were lower than early/mid concentrations, but absolute postnatal fGCM values appear to be in between early/mid concentrations. This dynamic might be due to the steep rise in fGCM concentrations from early to mid-gestation, which might have also been influenced by changes in rainfall and food availability at the beginning of the dry season in April/May. fGCM concentrations were higher during months with little rainfall. Since rainfall is a proxy for food availability (Koch et al. 2017; Rudolph et al. 2019), mothers might have been in poorer condition during periods of lower food availability, a state typically associated with elevated fGCM concentrations. Mothers that gave birth to an infant the previous year had higher fGCM concentrations, indicating that these mothers had to mobilize more energy or higher HPA activity and that generally higher GC levels in the mother (potentially due to her own early life experience) lead to a faster pace of life.

Most importantly, infants’ physical and behavioral developments were influenced by mothers’ prenatal fGCM concentrations. Specifically, infants of mothers with higher prenatal fGCM concentrations exhibited higher growth rates. Infants of mothers with higher early/mid prenatal fGCM concentrations were more active by spending more time foraging independently and being more active in all categories of play. Even though solitary locomotor and object play emerged earlier than social play (Malalaharivony et al. 2021), fGCM concentrations did not affect play types differently. In contrast, infants of mothers with low early/mid and postnatal fGCM concentrations were carried more, and those of mothers with higher postnatal GC levels spent more time in nipple contact. Time spent carrying infants predicted infants’ survival, suggesting that infants that were potentially in poorer condition had to be carried more. Hence, infants that were carried less often and were more independent were able to successfully navigate their first ecological bottleneck, i.e., the first dry season after weaning, a period in which about 62% of infants die (Kappeler and Fichtel 2012). Thus, infants’ physical and behavioral developments were presumably impacted by maternal fGCM concentrations, but it is equally possible that the demands of caring for an infant in relatively poor condition caused an increase in maternal fGCM.

While our study was not designed to formally test predictions of ultimate hypotheses about maternal effects, the observed patterns of growth and behavioral development during early infancy are possibly indicative of an internal PAR response. However, “the PAR and developmental constraints models can only be distinguished by comparing fitness-related traits in individuals from high- and low-quality early environments, when each of these sets of individuals experience both high- and low-quality adult conditions” (Lea et al. 2015), which was not possible in this study. Additional future research will be required to determine how prenatally stressed offspring manage to grow faster and play more, and whether the extra time spent foraging is sufficient to provide the necessary energetic support.

Variation in maternal fGCM concentrations

Maternal fGCM concentrations of Verreaux’s sifaka can be examined with respect to the costs of reproduction or seasonality, which are not independent in sifakas, and therefore challenging to disentangle (see also Charpentier et al. 2018). First, maternal GCs increased during the prenatal period and were higher than during the postnatal period, confirming results of previous studies in the same population (Rudolph et al. 2019, 2020). Even though lactation is the energetically most challenging reproductive activity for mammals (Hinde and Milligan 2011), several other studies also reported higher maternal GC levels during gestation (particularly late gestation) than during lactation (e.g., Rimbach et al. 2013; Berghänel et al. 2016; but see Starling et al. 2010). In fact, GC levels increase across gestation in most mammals (Edwards and Boonstra 2018; but see Scott et al. 2013 for artiodactyls).

These pregnancy-related elevations in GC output are likely caused by interactions of increased metabolic demands during pregnancy and activation of the HPA axis with concomitant stimulation of corticosteroid-binding globulin due to elevated levels of estrogens as well as placental production of cortisol (Edwards and Boonstra 2018). High levels of GCs may also prepare the body for the stressful period surrounding parturition (Edwards and Boonstra 2018) and probably trigger developmental changes that prepare the late fetus for the extra-uterine environment, particularly with respect to organ maturation (Fowden et al. 1998) and may therefore not reflect direct adaptations to females’ energetic costs of reproduction. Our finding of a positive link between pre- and postnatal maternal GCs, in contrast, points towards intrinsic factors related to individual energetic investments into reproduction. Our finding that mothers that had an infant the previous year had marginally higher GC levels than those that did not also indicates that some long-term costs of reproduction contributed to variation in maternal GC levels, suggesting that the physiological costs of reproduction go beyond direct and indirect costs previously characterized for mammals (Wells 2007b; Speakman 2008).

Second, maternal fGCM concentrations were higher during periods with low rainfall, which serves as a proxy for food availability in this seasonal habitat (Koch et al. 2017; Rudolph et al. 2019), but rainfall in the months before conception did not co-vary with fGCM concentrations. This may reflect the position of Verreaux’s sifakas along the continuum from capital to income breeders (Lewis and Kappeler 2005). A reduction in the quantity or quality of food has been shown to increase GC levels in several other species, including lemurs (Behie and Pavelka 2013, Chapman et al. 2015; Berghänel et al. 2016; Tecot et al. 2019; Rudolph et al. 2020), and may therefore reflect a response to compensate for reduced energy intake. Reduced food availability is particularly challenging for gregarious species because of feeding competition, which can be stressful for reproducing low-ranking individuals (Creel et al. 2013); subordinate reproduction has been regularly observed in our study population in previous years (Kappeler and Fichtel 2012). Because these sifakas inhabit forests that are highly seasonal, but in which rainfall and food availability is highly unpredictable from year to year (Dewar and Richard 2007; Lawler et al. 2009; but see Federman et al. 2017), it is likely that physiological adaptations are fine-tuned and superimposed upon predictable seasonal cycles (Reeder and Kramer 2005; Creel et al. 2013).

Effects of maternal GC levels on maternal investment and infant development

Our study revealed that variation in maternal GC levels was associated with several aspects of maternal care and infant development. First, variation in maternal stress levels was associated with patterns of maternal care. High maternal GC levels during the prenatal phase correlated with more explorative infants and low carry effort because infants of these mothers spent more time foraging independently and more time playing. High maternal GC during the postnatal phase correlated with infants who have more nipple contact and forage more while resting and being carried less. While mothers with lower fGCM levels carried their infants more, maternal GC levels had no effect on independent infant locomotion, presumably because infants also moved when their mothers did not. It would therefore be interesting to estimate maternal carrying effort as the proportion of total maternal locomotion to assess different maternal strategies: infant carrying vs. nursing plus independent infant locomotion (Kramer 1998; Harel et al. 2021). Further, time spent carrying infants predicted infant survival in the first 1.5 years, suggesting that infants that were potentially in poorer condition had to be carried for longer, but more detailed analyses of mothering styles are required to substantiate this idea. Moreover, long-term effects of early maternal adversity on maternal effort should also be considered in this context (Patterson et al. 2021).

Second, infants exhibited faster growth rates when mothers had higher prenatal GC levels, echoing findings of previous studies reporting a positive correlation between postnatal infant growth rates and maternal GC levels (Swolin-Eide et al. 2002; Hauser et al. 2007; Dantzer et al. 2013; Hinde et al. 2015; Berghänel et al. 2016). However, other studies reported the opposite effect, prompting Berghänel et al. (2017) to propose a model that reconciled these conflicting findings by suggesting that the effects of maternal GC output on infant growth depend on the infant’s specific developmental period. Because we have no data on fetal growth and our estimate of postnatal body mass growth is based on a single datum obtained after weaning, and arm length growth rates were measured only until an age of 6 months, we cannot assess the potential specific dynamics of infant growth patterns in this species. While it is likely that mothers elevate their GC levels during gestation as a result of reduced energetic intake and/or increased expenditure, this response has no detrimental effects on their current reproduction, i.e., their infants’ growth rates. It has been argued that mothers, through increasing prenatal GCs, adjust their infant’s life trajectory by accelerating infant’s life history pace altogether (Nettle and Bateson 2015), but we lack data on the long-term consequences on other life history traits, such as sexual maturation and longevity to evaluate this possibility. Because the infants of mothers with high prenatal GC levels developed faster and began foraging independently earlier, these stressed mothers benefit from an overall reduction of maternal investment, thereby making the best of a bad start of the current reproductive cycle (Jones 2005).

Finally, we found that arm length growth and time spent carrying predicted infant survival during the first 1.5 years of life. In Verreaux’s sifaka, survival during the first year of life has been found to represent the most challenging life stage, with more than half of infants dying (Richard et al. 2002; Lawler et al. 2009; Kappeler and Fichtel 2012). Thus, this relationship is important for the fitness of both mothers and infants, but it is difficult to evaluate because in our study, infant survival was not consistently linked to the two different growth estimates. Moreover, survival was not predicted by maternal GC levels or our estimates of infant’s energy input, i.e., time spent foraging or in nipple contact and therefore appears to be unrelated to how much energy infants obtained. Finally, mother’s age also did not predict early survival, although mothers in these two birth cohorts were rather old, with a mean age of 12.6 ± 4.6 years, including an 18-, 19-, and 20-year-old female. Female sifakas have an average life expectancy of 5 years (Colchero et al. 2021), and the oldest female in our long-term records was 21 years old. Hence, maternal senescence as described for many other mammals (Ivimey-Cook and Moorad 2020) did not influence infant pre-adult survival. However, since our sample size with 12 infants is small, limiting our analyses to one factor per model, and we had not many young mothers during the study period, the relative importance of each effect remains difficult to assess without additional data.

Conclusions

This study of a wild primate population in a seasonal habitat revealed that ecological and intrinsic effects on maternal GC concentrations are difficult to disentangle because responses to current climatic conditions, reproductive history, and current reproductive activities are superimposed. Maternal GC levels were profoundly linked to infant behavior and development, however. Maternal effects mediated by hormones are therefore prevalent in this species and appear to reveal a trade-off between maternal benefits and infant costs. As such, our study provides mixed evidence for beneficial effects of extended maternal GC levels and provides one of the first studies simultaneously examining the connections between environmental factors, maternal stress, and fitness proxies (Beehner and Bergman 2017; Campos et al. 2021).

Data availability

The datasets that were analyzed for this study are deposited under this link: https://osf.io/sgvxj/?view_only=7e306fa1a514422a938b982af88adc80

Code availability

The computer code that was used to analyze the data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Alberts SC (2019) Social influences on survival and reproduction: insights from a long-term study of wild baboons. J Anim Ecol 88:47–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12887

Altmann J (1974) Observational study of behavior sampling methods: sampling methods. Behaviour 49:227–267. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853974X00534

Animal Behaviour (2020) Guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioural research and teaching. Anim Behav 159:I-XI. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.11.002

Baayen RH (2008) Analyzing linguistic data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, Bates DM (2008) Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J Mem Lang 59:390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005

Balestri M, Barresi M, Campera M, Serra V, Ramanamanjato JB, Heistermann M, Donati G (2014) Habitat degradation and seasonality affect physiological stress levels of Eulemur collaris in littoral forest fragments. PLoS ONE 9:e107698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107698

Barr DJ, Levy R, Scheepers C, Tily HJ (2013) Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: keeping it maximal. J Mem Lang 68:255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2014) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. arXiv:1406.5823. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Beehner JC, Bergman TJ (2017) The next step for stress research in primates: to identify relationships between glucocorticoid secretion and fitness. Horm Behav 91:68–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.03.003

Behie AM, Pavelka MS (2013) Interacting roles of diet, cortisol levels, and parasites in determining population density of Belizean howler monkeys in a hurricane damaged forest fragment. In: Marsh LK, Chapman CA (eds) Primates in fragments. Springer, New York, pp 447–456

Berghänel A, Schülke O, Ostner J (2015) Locomotor play drives motor skill acquisition at the expense of growth: a life history trade-off. Sci Adv 1:e1500451. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500451

Berghänel A, Heistermann M, Schülke O, Ostner J (2016) Prenatal stress effects in a wild, long-lived primate: predictive adaptive responses in an unpredictable environment. Proc R Soc B 283:20161304. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.1304

Berghänel A, Heistermann M, Schülke O, Ostner J (2017) Prenatal stress accelerates offspring growth to compensate for reduced maternal investment across mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:E10658–E10666. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707152114

Bernardo J (1996) The particular maternal effect of propagule size, especially egg size: patterns, models, quality of evidence and interpretations. Am Zool 36:216–236. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/36.2.216

Bolker BM (2008) Ecological models and data in R. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Braga Goncalves I, Heistermann M, Santema P, Dantzer B, Mausbach J, Ganswindt A, Manser MB (2016) Validation of a fecal glucocorticoid assay to assess adrenocortical activity in meerkats using physiological and biological stimuli. PLoS ONE 11:e0153161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153161

Breuer T, Robbins MM, Boesch C (2007) Using photogrammetry and color scoring to assess sexual dimorphism in wild western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla). Am J Phys Anthropol 134:369–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20678

Brockman DK, Cobden AK, Whitten PL (2009) Birth season glucocorticoids are related to the presence of infants in sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi). Proc R Soc Lond B 276:1855–1863. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.1912

Campos FA, Archie EA, Gesquiere LR, Tung J, Altmann J, Alberts SC (2021) Glucocorticoid exposure predicts survival in female baboons. Sci Adv 7:eabf6759. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abf6759

Cavigelli SA (1999) Behavioural patterns associated with faecal cortisol levels in free-ranging female ring-tailed lemurs, Lemur catta. Anim Behav 57:935–944. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1998.1054

Cavigelli SA, Dubovick T, Levash W, Jolly A, Pitts A (2003) Female dominance status and fecal corticoids in a cooperative breeder with low reproductive skew: ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta). Horm Behav 43:166–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0018-506X(02)00031-4

Chapman CA, Schoof VAM, Bonnell TR, Gogarten JF, Calmé S (2015) Competing pressures on populations: long-term dynamics of food availability, food quality, disease, stress, and animal abundance. Phil Trans R Soc B 370:20140112. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0112

Charpentier MJE, Givalois L, Faurie C, Soghessa O, Simon F, Kappeler PM (2018) Seasonal glucocorticoid production correlates with a suite of small-magnitude environmental, demographic, and physiological effects in mandrills. Am J Phys Anthropol 165:20–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23329

Colchero F, Aburto JM, Archie EA et al (2021) The long lives of primates and the ‘invariant rate of ageing’ hypothesis. Nat Commun 12:3666. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23894-3

Creel S, Dantzer B, Goymann W, Rubenstein DR (2013) The ecology of stress: effects of the social environment. Funct Ecol 27:66–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02029.x

Crockford C, Samuni L, Vigilant L, Wittig RM (2020) Postweaning maternal care increases male chimpanzee reproductive success. Sci Adv 6:eaaz5746. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5746

Dantzer B, Newman AEM, Boonstra R, Palme R, Boutin S, Humphries MM, McAdam AG (2013) Density triggers maternal hormones that increase adaptive offspring growth in a wild mammal. Science 340:1215–1217. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235765

Dewar RE, Richard AF (2007) Evolution in the hypervariable environment of Madagascar. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:13723–13727. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0704346104

Edes AN, Crews DE (2017) Allostatic load and biological anthropology. Am J Phys Anthropol 162(Suppl 63):44–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23146

Edwards PD, Boonstra R (2018) Glucocorticoids and CBG during pregnancy in mammals: diversity, pattern, and function. Gen Comp Endocrinol 259:122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.11.012

Fardi S, Sauther ML, Cuozzo FP, Jacky IAY, Bernstein RM (2018) The effect of extreme weather events on hair cortisol and body weight in a wild ring-tailed lemur population (Lemur catta) in southwestern Madagascar. Am J Primatol 80:e22731. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22731

Federman S, Sinnott-Armstrong M, Baden AL, Chapman CA, Daly DC, Richard AR, Valenta K, Donoghue MJ (2017) The paucity of frugivores in Madagascar may not be due to unpredictable temperatures or fruit resources. PLoS ONE 12:e0168943. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168943

Fichtel C, Kraus C, Ganswindt A, Heistermann M (2007) Influence of reproductive season and rank on fecal glucocorticoid levels in free-ranging male Verreaux’s sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi). Horm Behav 51:640–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.03.005

Field A (2009) Discovering statistics using SPSS, in: an R companion to applied regression. Sage Publications, London

Forstmeier W, Schielzeth H (2011) Cryptic multiple hypotheses testing in linear models: overestimated effect sizes and the winner’s curse. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-010-1038-5

Fowden AL, Li J, Forhead AJ (1998) Glucocorticoids and the preparation for life after birth: are there long-term consequences of the life insurance? Proc Nutr Soc 57:113–122. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS19980017

Gabriel DN, Gould L, Cook S (2018) Crowding as a primary source of stress in an endangered fragment-dwelling strepsirrhine primate. Anim Conserv 21:76–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12375

Giesing ER, Suski CD, Warner RE, Bell AM (2011) Female sticklebacks transfer information via eggs: effects of maternal experience with predators on offspring. Proc R Soc Lond B 278:1753–1759. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.1819

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Spencer HG, Bateson P (2005) Environmental influences during development and their later consequences for health and disease: implications for the interpretation of empirical studies. Proc R Soc Lond B 272:671–677

Gould L, Ziegler TE, Wittwer DJ (2005) Effects of reproductive and social variables on fecal glucocorticoid levels in a sample of adult male ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) at the Beza Mahafaly Reserve, Madagascar. Am J Primatol 67:5–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20166

Grafen A (1988) On the uses of data on lifetime reproductive success. In: Clutton-Brock TH (ed) Reproductive success: studies of individual variation in contrasting breeding systems. Chicago University Press, Chicago, pp 454–471

Grey KR, Davis EP, Sandman CA, Glynn LM (2013) Human milk cortisol is associated with infant temperament. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38:1178–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.002

Guevara EE, Webster TH, Lawler RR et al (2021) Comparative genomic analysis of sifakas (Propithecus) reveals selection for folivory and high heterozygosity despite endangered status. Sci Adv 7:eabd2274. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd2274

Hämäläinen A, Heistermann M, Kraus C (2015) The stress of growing old: sex-and season-specific effects of age on allostatic load in wild grey mouse lemurs. Oecologia 178:1063–1075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-015-3297-3

Hanson MA, Gluckman PD (2014) Early developmental conditioning of later health and disease: physiology or pathophysiology? Physiol Rev 94:1027–1076. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00029.2013

Harel R, Loftus JC, Crofoot MC (2021) Locomotor compromises maintain group cohesion in baboon troops on the move. Proc R Soc B 288:20210839. https://doi/https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0839

Hauser J, Dettling-Artho A, Pilloud S, Maier C, Knapman A, Feldon J, Pryce CR (2007) Effects of prenatal dexamethasone treatment on postnatal physical, endocrine, and social development in the common marmoset monkey. Endocrinology 148:1813–1822. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2006-1306

Hawkley L, Capitanio JP (2020) Baboons, bonds, biology, and lessons about early life adversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:22628–22630. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015162117

Heistermann M, Palme R, Ganswindt A (2006) Comparison of different enzyme immunoassays for assessment of adrenocortical activity in primates based on fecal analysis. Am J Primatol 68:257–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20222

Hinde K (2013) Lactational programming of infant behavioral phenotype. In: Clancy KBH, Hinde K, Rutherford JN (eds) Building babies: primate development in proximate and ultimate perspective. Springer, New York, pp 187–207

Hinde K, Milligan LA (2011) Primate milk: proximate mechanisms and ultimate perspectives. Evol Anthropol 20:9–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.20289

Hinde K, Skibiel AL, Foster AB, Del Rosso L, Mendoza SP, Capitanio JP (2015) Cortisol in mother’s milk across lactation reflects maternal life history and predicts infant temperament. Behav Ecol 13:269–281. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/aru186

Ivimey-Cook E, Moorad J (2020) The diversity of maternal-age effects upon pre-adult survival across animal species. Proc R Soc B 287:20200972. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.0972

Jolly A (1966) Lemur behavior: a Madagascar field study. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Jones JH (2005) Fetal programming: adaptive life-history tactics or making the best of a bad start? Am J Hum Biol 17:22–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20099

Kalbitzer U, Heistermann M, Cheney D, Seyfarth R, Fischer J (2015) Social behavior and patterns of testosterone and glucocorticoid levels differ between male chacma and Guinea baboons. Horm Behav 75:100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.08.013

Kappeler PM, Fichtel C (2012) A 15-year perspective on the social organization and life history of sifaka in Kirindy Forest. In: Kappeler PM, Watts D.P (eds) Long-term field studies of primates. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 101–121

Koch F, Ganzhorn JU, Rothman JM, Chapman CA, Fichtel C (2017) Sex and seasonal differences in diet and nutrient intake in Verreaux’s sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi). Am J Primatol 79:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22595

Kramer PA (1998) The costs of human locomotion: maternal investment in child transport. Am J Phys Anthropol 107:71–85

Langenhof MR, Komdeur J (2018) Why and how the early-life environment affects development of coping behaviours. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72:34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2452-3

Lawler RR, Caswell H, Richard AF, Ratsirarson J, Dewar RE, Schwartz M (2009) Demography of Verreaux’s sifaka in a stochastic rainfall environment. Oecologia 161:491–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1382-1

Lea AJ, Altmann J, Alberts SC, Tung J (2015) Developmental constraints in a wild primate. Am Nat 185:809–821. https://doi.org/10.1086/681016

Lea AJ, Tung J, Archie EA, Alberts SC (2018) Developmental plasticity: bridging research in evolution and human health. Evol Med Pub Health 2017:162–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eox019

Lewis RJ, Kappeler PM (2005) Are Kirindy sifaka capital or income breeders? It depends. Am J Primatol 67:365–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20190

Louis EE, Sefczek TM, Bailey CA, Raharivololona B, Lewis R, Rakotomalala EJ (2020). Propithecus verreauxi. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2020: e.T18354A115572044. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T18354A115572044.en.

Love OP, Williams TD (2008) Plasticity in the adrenocortical response of a free-living vertebrate: the role of pre- and post-natal developmental stress. Horm Behav 54:496–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.01.006

Love OP, Chin EH, Wynne-Edwards KE, Williams TD (2005) Stress hormones: a link between maternal condition and sex-biased reproductive investment. Am Nat 166:751–766. https://doi.org/10.1086/497440

Love OP, McGowan PO, Sheriff MJ (2013) Maternal adversity and ecological stressors in natural populations: the role of stress axis programming in individuals, with implications for populations and communities. Funct Ecol 27:81–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02040.x

Lummaa V, Clutton-Brock TH (2002) Early development, survival and reproduction in humans. Trends Ecol Evol 17:141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02414-4

Maestripieri D (2018) Maternal influences on primate social development. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72:130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2547-x

Malalaharivony HS, Kappeler PM, Fichtel C (2021) Infant development and maternal care in wild Verreaux’s sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi). Int J Primatol (in press)

McCullagh P, Nelder JA (1989) Generalized linear models. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. Chapman & Hall, New York, pp 98–148

McGhee KE, Barbosa AJ, Bissell K, Darby NA, Foshee S (2021) Maternal stress during pregnancy affects activity, exploration and potential dispersal of daughters in an invasive fish. Anim Behav 171:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2020.11.003

Monaghan P (2008) Early growth conditions, phenotypic development and environmental change. Phil Trans R Soc B 363:1635–1645. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.0011

Moore MP, Whiteman HH, Martin RA (2019) A mother’s legacy: the strength of maternal effects in animal populations. Ecol Lett 22:1620–1628. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13351

Morimoto J, Ponton F, Tychsen I, Cassar J, Wigby S (2017) Interactions between the developmental and adult social environments mediate group dynamics and offspring traits in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci Rep 7:3574. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03505-2

Mouton JC, Duckworth RA (2021) Maternally derived hormones, neurosteroids and the development of behaviour. Proc R Soc B 288:20202467. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.2467

Nettle D, Bateson M (2015) Adaptive developmental plasticity: what is it, how can we recognize it and when can it evolve? Proc R Soc B 282:20151005. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1005

Nettle D, Frankenhuis WE, Rickard IJ (2013) The evolution of predictive adaptive responses in human life history. Proc R Soc B 280:20131343. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.1343

Nieuwenhuis R, te Grotenhuis M, Pelzer B (2012) Influence.ME: tools for detecting influential data in mixed effects models. R J 4:38–47. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2012-011

Ostner J, Kappeler PM, Heistermann M (2008) Androgen and glucocorticoid levels reflect seasonally occurring social challenges in male redfronted lemurs (Eulemur fulvus rufus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 62:627–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-007-0487-y

Patel ER (2007) Non-maternal infant care in wild silky sifakas (Propithecus candidus). Lemur News 12:39–42

Patin V, Lordi B, Vincent A, Thoumas JL, Vaudry H, Caston J (2002) Effects of prenatal stress on maternal behavior in the rat. Dev Brain Res 139:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00491-1

Patterson SK, Hinde K, Bond AB, Trumble BC, Strum SC (2021) Silk JB (2021) Effects of early life adversity on maternal effort and glucocorticoids in wild olive baboons. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 75:114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-03056-7

Pride RE (2005) Optimal group size and seasonal stress in ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta). Behav Ecol 16:550–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ari025

Queen JP, Quinn GP, Keough MJ (2002) Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Reeder DM, Kramer KM (2005) Stress in free-ranging mammals: integrating physiology, ecology, and natural history. J Mammal 86:225–235. https://doi.org/10.1644/BHE-003.1

Richard AF, Dewar RE, Schwartz M, Ratsirarson J (2002) Life in the slow lane? Demography and life histories of male and female sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi verreauxi). J Zool 256:421–436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952836902000468

Rimbach R, Heymann EW, Link A, Heistermann M (2013) Validation of enzyme immunoassay for assessing adrenocortical activity and evaluation of factors that affects levels of fecal glucocorticoid metabolites in two New World primates. Gen Comp Endocrinol 191:13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.05.010

Rosenbaum S, Zeng S, Campos FA, Gesquiere LR, Altmann J, Alberts SC, Li F, Archie EA (2020) Social bonds do not mediate the relationship between early adversity and adult glucocorticoids in wild baboons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:20052–20062. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004524117

Ross AC (2020) Lactating Coquerel’s sifaka (Propithecus coquereli) exhibit reduced stress responses in comparison to males and nonlactating females. Am J Primatol 82:e23103. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23103

Rudolph K, Fichtel C, Schneider D, Heistermann M, Koch F, Daniel R, Kappeler PM (2019) One size fits all? Relationships among group size, health, and ecology indicate a lack of an optimal group size in a wild lemur population. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 73:132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-019-2746-0

Rudolph K, Fichtel C, Heistermann M, Kappeler PM (2020) Dynamics and determinants of glucocorticoid metabolite concentrations in wild Verreaux’s sifakas. Horm Behav 124:104760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104760

Sachser N, Hennessy MB, Kaiser S (2018) The adaptive shaping of social behavioural phenotypes during adolescence. Biol Lett 14:20180536. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0536

Schielzeth H (2010) Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Method Ecol Evol 1:103–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00012.x

Schielzeth H, Forstmeier W (2009) Conclusions beyond support: overconfident estimates in mixed models. Behav Ecol 20:416–420. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arn145

Schülke O, Ostner J, Berghänel A (2019) Prenatal maternal stress effects on the development of primate social behavior. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 73:128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-019-2729-1

Scott IC, Asher GW, Barrell GK, Juan JV (2013) Voluntary food intake of pregnant and non-pregnant red deer hinds. Livestock Sci 158:230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2013.04.021

Sheriff MJ, Love OP (2013) Determining the adaptive potential of maternal stress. Ecol Lett 16:271–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12042

Sheriff MJ, Bell A, Boonstra R, Dantzer B, Lavergne SG, McGhee KE, MacLeod KJ, Winandy L, Zimmer C, Love PO (2017) Integrating ecological and evolutionary context in the study of maternal stress. Integr Comp Biol 57:437–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icx105

Shutt K, Setchell JM, Heistermann M (2012) Non-invasive monitoring of physiological stress in the Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla): validation of a fecal glucocorticoid assay and methods for practical application in the field. Gen Comp Endocrinol 170:167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.08.008

Snyder-Mackler N, Burger JR, Gaydosh L et al (2020) Social determinants of health and survival in humans and other animals. Science 368:eaax9553. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax9553

Speakman JR (2008) The physiological costs of reproduction in small mammals. Phil Trans R Soc B 363:375–398. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2145

Starling AP, Charpentier MJE, Fitzpatrick C, Scordato ES, Drea CM (2010) Seasonality, sociality, and reproduction: long-term stressors of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta). Horm Behav 57:76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.09.016

Sullivan EC, Hinde K, Mendoza SP, Capitanio JP (2011) Cortisol concentrations in the milk of rhesus monkey mothers are associated with confident temperament in sons, but not daughters. Dev Psychobiol 53:96–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20483

Swolin-Eide D, Dahlgren J, Nilsson C, Wikland KA, Holmang A, Ohlsson C (2002) Affected skeletal growth but normal bone mineralization in rat offspring after prenatal dexamethasone exposure. J Endocrinol 174:411–418. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.0.1740411

Tecot SR, Irwin MT, Raharison J-L (2019) Faecal glucocorticoid metabolite profiles in diademed sifakas increase during seasonal fruit scarcity with interactive effects of age/sex class and habitat degradation. Cons Physiol 7:coz001. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/coz001

Tecot SR (2008) Seasonality and predictability: the hormonal and behavioral responses of the red-bellied lemur, Eulemur rubriventer, in southeastern Madagascar. PhD thesis, University of Texas, Austin

Tecot SR (2013) Variable energetic strategies in disturbed and undisturbed rain forests: Eulemur rubriventer fecal cortisol levels in South-Eastern Madagascar. In: Masters J, Gamba M, Génin F (eds) Leaping ahead. Developments in primatology: progress and prospects. Springer, New York, pp 185‑195

Therneau T, Crowson C, Atkinson E (2020) Mulitstate models and competing risks. CRAN-R, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/vignettes/compete.pdf

Thompson NA, Cords M (2020) Early life maternal sociality predicts juvenile sociality in blue monkeys. Am J Primatol 82:e23039. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23039

Tung J, Archie EA, Altmann J, Alberts SC (2016) Cumulative early life adversity predicts longevity in wild baboons. Nat Commun 7:11181. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11181

van Noordwijk MA (2012) From maternal investment to lifetime maternal care. In: Mitani JC, Call J, Kappeler PM, Palombit R, Silk JB (eds) The evolution of primate societies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 321–342

van Noordwijk MA, Kuzawa CW, van Schaik CP (2013) The evolution of the patterning of human lactation: a comparative perspective. Evol Anthropol 22:202–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21368

Veru F, Laplante DP, Luheshi G, King S (2014) Prenatal maternal stress exposure and immune function in the offspring. Stress 17:133–148. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2013.876404

Weibel CJ, Tung J, Alberts SC, Archie EA (2020) Accelerated reproduction is not an adaptive response to early-life adversity in wild baboons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:24909. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004018117

Weinstock M (2008) The long-term behavioural consequences of prenatal stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32:1073–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.002

Welcker J, Harding AMA, Kitaysky AS, Speakman JR, Gabrielsen GW (2009) Daily energy expenditure increases in response to low nutritional stress in an Arctic-breeding seabird with no effect on mortality. Funct Ecol 23:1081–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01585.x

Wells JCK (2007a) Flaws in the theory of predictive adaptive responses. Trends Endocrin Met 18:331–337

Wells JCK (2007b) The thrifty phenotype as an adaptive maternal effect. Biol Rev 82:143–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2006.00007.x

Zipple MN, Altmann J, Campos FA et al (2021) Maternal death and offspring fitness in multiple wild primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118:e2015317118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015317118

Zipple MN, Archie EA, Tung J, Altmann J, Alberts SC (2019) Intergenerational effects of early adversity on survival in wild baboons. eLife 8:e47433. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47433

Acknowledgements

We thank the Malagasy Ministry of the Environment and the CNFEREF Morondava for authorizing our work, the Kirindy field assistants for help with data and sample collection, Roger Mundry for invaluable statistical advice, and Maria van Noordwijk and two anonymous referees for offering exceptionally insightful and constructive comments on this paper.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), grant number Ka 1082/29–565 2, awarded to PMK as one project of the DFG Research Group “Sociality and Health in Primates.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HSM was primarily responsible for data collection, HSM and CF analyzed data, MH performed hormone analysis, and PMK drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study adhered to the Guidelines for the Treatment of Animals in Behavioral Research and Teaching (Animal Behaviour 2020) and the legal requirements of the country (Madagascar) in which the work was carried out. The protocol for this research was approved by the Malagasy Ministry of the Environment, Water, and Forests (245/17/MEFF/SG/DGF/DSAP/SCB.Re, 047, 215/18/MEFF/SG/DGF/DSAP/SCB.Re, 053/19/MEDD/SG/DGF/DSAP/SCB.Re).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors consent to the publication of this manuscript in Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by M. A van Noordwijk.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malalaharivony, H.S., Fichtel, C., Heistermann, M. et al. Maternal stress effects on infant development in wild Verreaux's sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 75, 143 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-03085-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-03085-2