Abstract

Background

The presentation of medical topics in the cinema can greatly influence the public’s understanding and perception of a medical field, with regard to the doctors and surgeons, medical diagnosis, and treatment and outcome expectations. This study aims to evaluate the representation of plastic surgery in commercial films that include a character with a link to plastic surgery, either as a patient or surgeon.

Methods

The international film databases Internet Movie Database (IMDb), The American Film Institute (AFI), and British Film Institute (BFI) were searched from 1919 to 2019 to identify feature-length films with a link to plastic surgery. Movies were visualized and analyzed to identify themes, and the portrayal of plastic surgery was rated negative or positive, and realistic or unrealistic.

Results

A total of 223 films were identified from 1919 to 2019, produced across 19 countries. Various genres were identified including drama (41), comedy (25), and crime (23). A total of 172 patient characters and 57 surgeon characters were identified as major roles, and a further 102 surgeons as minor roles. Disparities were noted in presentation of surgeons, both in terms of race and gender, with the vast majority of surgeons being white and male. In total only 11 female surgeons were portrayed and only one black surgeon. Thirteen themes emerged: face transplantation, crime, future society, surgeon mental status, body dysmorphic disorder, vanity, anti-aging, race, reconstructive surgery, deformity, scarring, burns, and gender transitioning. The majority of films (146/223) provide an unrealistic view of plastic surgery, painted under a negative light (80/146). Only 20 films provide a positive realistic image (24/77).

Conclusions

There exists a complicated relationship between plastic surgery and its representation on film. Surgical and aesthetic interventions are portrayed unrealistically, with surgeons and patients presented negatively, perpetuating stigma, particularly with regard to cosmetic surgery. Cinema is also characterized by lack of representation of female and non-white surgeons. Recruitment of surgeons as technical advisors would help present a more realistic, representative view, without necessarily sacrificing creativity.

Level of evidence: Not ratable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cinema is a powerful vehicle for depicting any topic, and medicine is no exception. Film not only has the ability to reach millions of viewers, but also has the ability to create a certain image for a medical field. Consequently, films have the power to determine patients’ understanding of a medical topic, their assumptions of doctors and surgeons, and their expectations in terms of diagnosis, treatment, recovery, and outcomes.

Several studies have looked at the presentation of medical topics in film or in the media in general and how this representation impacts the general understanding of the public. Topics analyzed include the portrayal of mental health, [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] with some focusing on Asperger syndrome, [10] dissociative identity disorder, [11] and electroconvulsive therapy. [12, 13] Other topics include assisted suicide, [14] locked-in syndrome [15] and coma, [16] cancer [17] and childhood cancer, [18] anti-bacterial usage, [19] immunization, [20] movement disorders, [21] and face transplantation. [22] In terms of healthcare workers, studies have looked at the representation of pharmacists, [23] doctors, [24,25,26], and neurosurgeons. [27].

In addition, film has been shown to influence our behavior, including leading to increased alcohol consumption, [28,29,30,31] smoking, [32,33,34,35,36] gun use, [37, 38] and unsafe sexual behavior. [39,40,41,42,43].

The increased presentation of cosmetic surgery in the cinema may not be merely a reflection of changes in society, but rather cinema may be contributing to the increase through de-stigmatization of plastic surgery. Likewise, besides shaping the perception of plastic surgery, cinema may also be able to modify and even establish beauty standards.

Relevant to this, a 1993 study attempted to look at the representation of plastic surgery on film. [44] This study is now, however, limited in many ways. First, given that at the time of publication, online film databases were only just beginning to be established, the study used libraries to screen film reviews to identify titles and, therefore, is far from inclusive. In addition, as the study is almost 30 years old, it is now outdated. Finally, the study did not attempt to draw conclusions from quantitative research, but rather they stratified the movies according to genre and offered a qualitative description.

There has yet to be a systematic evaluation of the representation of plastic surgery in the cinema, particularly with regard to the realism of procedures and surgeons. Through our study, we will identify films produced in the last century that feature plastic surgery. We aim to analyze these films qualitatively and quantitively to draw conclusions on the distribution and changes through the decades, across countries and genres. Representation of surgeon minorities, in terms of race and gender, will also be explored. Overall, we seek to provide conclusions on the overall picture presented, exploring whether this picture is realistic, representative, or positive.

Methods

Sample selection

A comprehensive search was performed using the international databases and film sources: Internet Movie Database (IMDb), The American Film Institute (AFI), and British Film Institute (BFI). All databases were freely available online. The search was performed by two individual researchers (ACP, AMP). The databases were searched from 01.01.1919 to 01.01.2021 using the following keywords: plastic surgery/surgeon, reconstructive surgery/surgeon, cosmetic surgery/surgeon, (a)esthetic surgery/surgeon, and face transplant. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) feature-length films; (2) in English or with English subtitles; and (3) portraying a character with an explicit or implied link to plastic surgery, either as a patient or healthcare professional. Documentaries and shorts (< 50 min) were excluded. Movies were visualized and analyzed by a physician and a film analyst (ACP, AMP). Films were selected via a two-stage process. The titles and full summary of the films were first independently screened by two reviewers (ACP, AP). In a second stage, available full films were visualized and evaluated for eligibility (ACP, AP, YE, AH). If the film was not available to watch, press releases and reviews were surveyed.

Data extraction

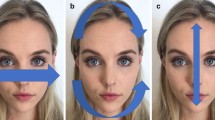

Data from selected films were extracted into a dedicated spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel® 2017 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The following data were extracted: title, year, country, genre, technical specs (color and sound), fictional character, role of character linked to plastic surgery (Surgeon/Patient and Minor/Major), gender of patient and surgeon, race of surgeon, role of plastic surgery in film narrative (Minor/Major), identified themes, overall presentation of plastic surgery (Negative/Neutral/Positive and Realistic/Unrealistic). Characters were deemed major if they were in a main or supporting role. The role of plastic surgery in the film was considered major if the film would not make sense without the inclusion of plastic surgery. Films were deemed unrealistic if they featured any of the following: (a) the procedure portrayed was scientifically inaccurate, (b) the clinical outcome of the surgery was unrealistic, (c) the post-surgical recovery process and timeline were unrealistic; (d) the post-surgical/intervention side-effects were unrealistic. Realism was evaluated by a plastic surgeon (VH). Seminal events in the field of plastic surgery that are depicted on film were identified and their timeline compared with reality.

Results

The selection process yielded 738 films from IMDb, with a further 177 added from the AFI and 8 from the BFI. Following title and full summary screening, 223 films were selected. Of these, 211 were viewed in their entirety. Twelve movies were unavailable to watch, nine of which were silent, printed on nitrate stock film, and presumed lost (Fig. 1). A minimum of 10 films were produced per decade from 1919 to 2019 with 86 films produced since 2000 (Fig. 2a). No 2020 films were found, reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cinema. Peaks in films featuring plastic surgery were seen in the 1930s, 1960s, and 2000s, three decades signaling the start of cinematic eras—the golden age of Hollywood, New Hollywood, and contemporary era, respectively—and consequently mass film production. The trend of plastic surgery film production follows, on average, the overall film production trend. A total of 19 countries divided broadly into 5 regions were identified to have produced films featuring plastic surgery, with the majority produced in North America (149), Europe (31), and Asia (26; Fig. 2b). Seventy-three films were black and white, 12 technicolor, and 138 color (Fig. 2c). Genres were grouped into 7 broad categories: drama and film noir (drama, film-noir, melodrama), crime and mystery, comedy and satire (comedy, dark-comedy, satire, romantic comedy), horror, science-fiction and animation (animation, horror, science-fiction, thriller), action/war and western (action, adventure, war, western) biography and musical, with the majority of films belonging to drama and film noir (Fig. 2d). Plastic surgery had a major role in 105 films and a minor role in 118 films. The films tended to either focus on patients or surgeons with 172 patient characters and 57 surgeon characters identified as the focus in films. A further 102 surgeons were portrayed in less significant roles (Fig. 2e).

Film distribution. a Decades. Films featuring plastic surgery have been produced since 1919 with production showing an upward trend. Peaks are seen in the 1930s, 1960s, and 2000s. The trend is shown in comparison to the total number of films produced (as listed on IMDb). b Countries. Films were produced in 5 regions and 19 countries. 149 films originated in North America (USA 143; Canada 6), 32 in Europe (Belgium 1, Czechia 1, France 17, Germany 3, Italy 3, Poland 1, Russia 1, Spain 4, Sweden 1) 12 in the UK, 26 in Asia (China 2, Hong Kong 4, India 6, Japan 7, South Korea 7) and 4 in Latin America (Mexico 3, Venezuela 1). c Technical. The majority of films were in color, with a small number in technicolor. 13 films were silent. d Genres. A total of 19 genres were identified and were grouped into seven broad categories: drama and film noir (54: drama 41, film-noir 9, melodrama 4), crime and mystery (37: crime 23, mystery 14), comedy and satire (48: comedy 25, dark-comedy 7, satire 2, romance 14), horror/sci-fi and animation (48: animation 2, horror 22, sci-fi 13, thriller 11), action, war and western (31: action 17, adventure 7, war 5, western 2) biography (3) and musical (2). e Surgeon portrayal. 57 surgeon characters were identified as a major focus and a further 102 surgeons as minor roles. The majority of surgeons were white and male, with only 11 total female surgeons presented with 9 in major roles. No major roles were portrayed by Hispanic and black ethnic minorities

Racial representation

Of the 57 surgeons identified as the main focus in films, 53 were White and four were Asian (Fig. 2e). Of the four Asian surgeons, two were cast in a Japanese film and two in a South Korean film. Of the 102 surgeons with less significant roles, the majority were White (83), followed by Asian (11), Hispanic (6), and Black and mixed race (2). Interestingly, two films cast Hispanic non-white actors as white surgeons: Miss Muerte (1966) and Macabra: La Mano del Diablo (1981). The black surgeon was portrayed in the film Johnny Handsome (1989). The mixed-race actor was cast in the Punisher: War Zone (2008). Of the 11 Asian actors in minor roles as surgeons, four were cast in Indian, two in Japanese, and two in South Korean films. Three Asian actors were cast in a UK film (Womanhunt 1962) and US films (Smile 2005; Predestination 2014).

Gender representation

In terms of gender representation, nine of the 57 surgeons in major roles were female and 48 were male (Fig. 2e). Of the further 102 surgeons in less significant roles, two were female and 100 were male. Of the 11 films portraying female surgeons, four were from before the year 2000: The Right to Romance (1933), Bedside Manner (1945), Miss Muerte (1966), and Flesh Feast (1970). Furthermore, three were Asian films: Ki-re-i? (2004), Sin-de-rel-la (2006), and Herutâ Sukerutâ (2012). Of the 172 patient characters, 69 were female and 103 male.

Themes

A total of 13 themes were identified as shown in Fig. 3a and b, with some films featuring more than one theme. The earliest film depicting each theme is summarized in Table 1.

Film themes. a Distribution. 13 themes were identified, shown here under 9 broad categories. Cosmetic (vanity and anti-aging), Face transplantation, Reconstructive (surgery, deformity, scarring, burns), crime, surgeon mental status, body dysmorphic disorder, future society, race and gender transitioning. Most films depicted more than one theme, with a total of 419 themes depicted. b Film titles with themes identified. All 223 films are shown with year of production highlighting which of 13 themes, face transplantation, crime, future society, surgeon mental status, obsession (body dysmorphic disorder), vanity, anti-aging, race, reconstructive surgery, deformity, scarring, burns and gender transitioning, were present in each film

Overall representation of plastic surgery

The majority of films (146/223) provide an unrealistic view of plastic surgery (Fig. 4a). Of these unrealistic films, most present plastic surgery under a negative light (80), with 40 presenting a neutral image and 26 a positive image. Of the films providing a realistic view (77/223), most present a neutral image (33), followed by a negative image (24) and only 20 films provide a positive image (Fig. 4b). An increasing number of realistic films are being produced with a peak in the 2000s, although this may be a general trend in film production increase as unrealistic films have also been increasing. In terms of positive films, there are two peaks, one in the first two decades (1919–1939) where most positive films were unrealistic, and one in the last two decades (2000–2019) where most are realistic. Negative portrayal is also on the rise, with realistic and negative peaking in the last decade (2010s). The unrealistic and negative films showed two peaks, in the 1960s and in the last decade (2010s).

Image of plastic surgery. a Overall representation. Most films (146/223) are unrealistic and negative (80/146). Only 20 films are realistic and positive (20/77). b Presentation over time. Realistic films (R) have been showing an increasing trend, peaking in the 2000s, although unrealistic films (U) have also been increasing over time, peaking in the 2010s. Most positive films produced in the first two decades (1919–1939) were unrealistic, whereas most positive films produced in the last two decades (2000–2019) were realistic. Realistic and negative portrayal [R(-ve)] is also on the rise, with most films in the category produced in the last decade (2010s). Unrealistic and negative [U(-ve)] showed two peaks, one in the 1960s and one in the 2010s. c Plastic surgery film and reality timeline. Comparison of the actual timeline of 12 seminal events in modern plastic surgery and the timeline of their depiction in the cinema. Events were either depicted on film prior to becoming a reality, such as face transplantation and female plastic surgeons, or occurred in reality first to inspire depiction on film, such as reconstructive surgery and botulinum injections

Seminal events in the field of plastic surgery were identified, and their timeline was compared to the timeline of depiction on film (Fig. 4c). Specifically 12 events were identified as seminal: reconstructive surgery, two descriptions of “race modification” surgery (double eyelid and Jewish rhinoplasty), facelift surgery, gender re-assignment surgery, two minority representations in surgery (female and black surgeons), silicone breast augmentation, recognition of body dysmorphic disorder, introduction of botulinum toxin injections, law evasion through plastic surgery, and face transplantation surgery.

Discussion

This study is the first to quantitively analyze the depiction of plastic surgery in the cinema, a topic that has in recent decades become a staple in film production. Over the past century, more than 200 films have been produced which depict plastic surgeons or patients. Although such portrayals are not limited to a specific country or genre, the overall image presented is unrealistic and negative. Plastic surgeons are often depicted as mad scientists forcibly performing surgeries on their victims. In other frequent scenarios, plastic surgeons are assisting criminals and gangsters to evade the law through face transplantations and outer appearance modifications. If movies focus on the patients, they are portrayed as obsessive, vain, and characterized by mental disorders.

Comparison of the actual timeline of identified seminal events and the timeline of their depiction in the cinema showed that some events pre-dated their depiction in the cinema—life inspiring art—such as birth of modern reconstructive surgery by Dr. Harrold Gillies in 1917 and prompt depiction of this 2 years later in the silent film The Better Wife. Gender-reassignment surgery, on the other hand, was first performed in 1922 but was only depicted in the cinema in 1999. Other events were first depicted on film years before becoming a medical reality—art inspiring life—such as face transplantation, female plastic surgeons, and law evasion through facial modification.

Given its richness, the field of plastic surgery provides a vast number of themes to draw inspiration from. Our “Theme Heatmap” shows a clear shift from face transplantation and crime to vanity and anti-aging themes. Vanity and anti-aging themes began to be frequently depicted as early as the 1960s, becoming increasingly prevalent from the mid-1980s onwards. This may be a reflection of society’s perception of plastic surgery; as cosmetic surgery becomes more prevalent and accepted, it also becomes more common in film. This theme shift could also be reflective of society’s general gravitation from survival (reconstruction) to vanity (aesthetic modification). Cinema, similarly to other media, is in a position that allows it to determine societal beauty standards, while also simultaneously gaining inspiration from society. Establishing whether society inspires cinema or whether cinema influences society would be a difficult task as likely the truth lies somewhere in the middle.

Considering identity switch and face transplantation, the 1956 French film Les Yeux sans Visage portrays in gruesome detail a full-face transplant surgery, as well as later rejection. Notoriously, at the film’s premiere, members of the audience fainted after a face removal scene. [22] In terms of the realism of this film, although some details of the surgery and transplant rejection are not too far from reality, especially given the mid-century understanding of transplantation, the film was way ahead of its time and face transplantation only became a medical reality in 2005.

Another important subject in plastic surgery is gender dysphoria. With more than 25 million people worldwide with gender dysphoria, one million people in the USA identifying as transgender, and up to 40% of transgender people undergoing surgery, it was surprising that the theme least explored was gender re-assigment. [45,46,47,48] This discrepancy likely reflects “stigma” and “taboo” around the subject. Two influential films came from the same director, Pedro Almodóvar. In his 1999 drama Todo Sobre Mi Madre, there is a powerful scene of a transgender actor listing all the surgeries she has had for her transition, including her eyes, lips, chin, cheeks, and breasts. She explains that “the more you resemble what you’ve dreamed of being, the more authentic you are,” clearly portraying how gender dysphoria is experienced and how surgical transitioning can be beneficial for some patients. [49] In his film La Piel Que Habito, we see gender reassignment through a different lens, one of body imprisonment, a topic well described in the literature. [50, 51] In this film, Dr. Ledgard kidnaps a man and forcibly performs gender-reassignment surgery on him. Although the patient now has the body of a woman, the film clarifies that he still identifies as a man: gender is shown not to equal body but rather identity. Gender transitioning is a topic of major interest in plastic surgery, and appropriate depiction in the cinema could have a positive impact on social education and acceptance.

Racial themes were also importantly noted. Ever since the “Jewish Nose” was described by Dr. Jerome Webster as a “deformity” requiring surgery, rhinoplasty in the Jewish population has become more prevalent, and consequently more widespread in the cinema. [52,53,54] A Serious Man (2019) uses the Jewish rhinoplasty as a comedic device—a daughter is saving up for a rhinoplasty by stealing from her father—to criticize “social issues,” specifically Jewish Americanization. In the 2011 South Korean movie Sseoni, one of the characters obsesses over having double eyelid surgery. Although ethnic noses are becoming more and more acceptable and patients often choose to have surgery that preserves some signs of their ethnicity, double eyelid surgery is the most commonly performed cosmetic surgery in Asia and is on the rise. [55,56,57].

Not only are the films not realistic in terms of the presentation of the character of surgeons and patients, but cinema has also failed to reflect surgeons in terms of minority representation. Initially, cinema appeared to be making positive strides in terms of gender representation. The first film to present a female surgeon did so in 1933 (The Right to Romance) and positively, as renowned, ambitious surgeon with her own surgical room. This was well ahead of reality; the first female plastic surgeon, Dr Alma Dea Morani, was in reality only first recognized by the American College of Surgeons in 1948, when she was allowed to operate only off-hours so that male colleagues were not there. [58, 59].

In general though, most films pre- and post-dating this film have presented surgeons as divine creators in the form of white males. This is not representative of reality. Women surgeons in the US currently comprise 40% of integrated plastic surgery programs, up from 14% in 1990. [59] In terms of race, in 2014 in the USA, 22% of plastic surgery residents were Asian, 8% were Hispanic, and 4% were Black. [60] Consequently, although plastic surgery does indeed demonstrate lower representation of Black and Hispanic surgeons compared with other surgical fields, the representation on film is significantly lower. [61] It should also be noted that in recent cinema, even when women are portrayed as surgeons, they tend to be presented negatively. Specifically, seven of the 11 female surgeons are portrayed as “psychopathic surgeons” performing gruesome surgeries, driven by madness or revenge. Depiction of positive role models in the cinema, in the form of female and non-white successful benevolent surgeons, could play a role in increasing diversity in plastic surgery.

With relevance to the COVID-19 pandemic, we identified no films from 2020 featuring plastic surgery. This is reflective of the general contraction of the film industry and the negative repercussions of the pandemic on film production. However, it should be noted that going forward, it is possible that the COVID-19 pandemic may inspire cinema with movies featuring lockdowns already being released in 2021. Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 has impacted the field of plastic surgery [62] with reports supporting that interest in aesthetic procedures increased in 2020 despite the ongoing pandemic. [63] It is, therefore, possible that future plotlines may amalgamate themes of pandemics and their impact on surgeons and surgical patients.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the largest to date to investigate plastic surgery portrayal in the cinema in a systematic manner. Inclusion of a large number of films, across 19 countries and in multiple different languages, makes this study powerful. In addition, not restricting films to a certain genre or era limited this study’s selection bias. To our knowledge, this is the first study to draw conclusions on gender and race representation, as well as on the overall realism of the portrayal of plastic surgery in the cinema. This is also the first study to include assessments by a film analyst (AMP) allowing us to explore the films through the non-physician perspective. Despite these strengths, as with all studies, this study has limitations. First, although our search was extensive and covered three film databases, including IMDb, the largest online film database, not all relevant films may have been identified. This is particularly true for foreign language films, as these may not have been listed on the databases searched or may have been excluded due to lack of subtitles creating a form of language and selection bias. The limited number of identified Chinese and South Korean films may be reflective of this bias, especially given that the rate of cosmetic surgery (13.1 per 1000 people) in South Korea is the highest in the world. [64, 65] The IMDb database is, however, currently the most validated and comprehensive search tool available for film identification. [18, 20, 21, 23, 66] Furthermore, similar to the methodology of previous research, we excluded non-cinema movies, including straight-to-video and television movies, as the cultural impact of cinema feature films is more significant given its more widespread distribution. [20] We also excluded documentaries as we wanted to explore cinema from a creativity and imagination standpoint. Our study was not designed to assess the cultural impact of films through analysis of financial data (i.e., box office figures) or MetaCritic scores as previously studied. [20, 67] Nor did we investigate how our included films can influence societal behavior as we believe these three topics have merit as independent studies that warrant future research. The effect of cinematic portrayals of plastic surgery, particularly those that are negative and unrealistic, on viewers’ understanding and expectations of the field are not yet known. The aim of our study was to characterize the portrayal through the eras and across genres and countries to offer the overall image presented, and elucidate whether that image changed over time.

Conclusions

Cinema can immensely influence societal culture. Society in turn, in a type of inspiration-loop, determines cinematic themes. Our analysis highlights that the relationship between plastic surgery and its cultural context is a complicated one. Unrealistic portrayal of surgical and aesthetic interventions and negative portrayal of surgeons and patients not only creates unattainable expectations but also perpetuates stigma. Diversity in plastic surgery has increased through the years, both in terms of gender and race, but cinema has failed to catch on. Overall, recruitment of surgeons as technical advisors would help present a more realistic, representative view, without necessarily sacrificing creativity.

References

Leistedt SJ, Linkowski P (2014) Psychopathy and the cinema: fact or fiction? J Forensic Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12359

Orchowski LM, Spickard BA, McNamara JR (2006) Cinema and the valuing of psychotherapy: implications for clinical practice. Prof Psychol Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.37.5.506

Kelly BD (2006) Psychiatry in contemporary Irish cinema: a qualitative study. Ir J Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0790966700009617

Mangala R, Thara R (2009) Mental health in Tamil cinema. Int Rev Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260902748068

McCann E, Huntley-Moore S (2016) Madness in the movies: an evaluation of the use of cinema to explore mental health issues in nurse education. Nurse Educ Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.09.009

Menon KV, Ranjith G (2009) Malayalam cinema and mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260902748043

Hyler SE (1988) DSM-III at the cinema: madness in the movies. Compr Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440X(88)90014-4

Prasad CG, Babu GN, Chandra PS, Chaturvedi SK (2009) Chitrachanchala (Pictures of unstable mind): mental health themes in Kannada cinema. Int Rev Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260902747037

Fountoulakis K et al (1998) The concept of mental disorder in Greek cinema. Acta Psychiatr Scand. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10093.x

Pourre F, Aubert E, Andanson J, Raynaud JP (2012) Asperger syndrome in contemporary fictions. Encephale. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2011.12.009

Byrne P (2001) The butler(s) DID it - dissociative identity disorder in cinema. Med Humanit. https://doi.org/10.1136/mh.27.1.26

McDonald A, Walter G (2009) Hollywood and ECT. Int Rev Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260902747888

Andrade C, Shah N, Venkatesh BK (2010) The depiction of electroconvulsive therapy in Hindi cinema. J ECT. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181d017ba

Schmidt KW (2017) Assisted suicide in the movies – what is (not) shown? Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforsch - Gesundheitsschutz. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-016-2474-9

Collado-Vázquez S, Carrillo JM (2012) Locked in syndrome in literature cinema and television. Rev Neurol. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.5409.2012012

Wijdicks EFM, Wijdicks CA (2006) The portrayal of coma in contemporary motion pictures. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000210497.62202.e9

Rosti G et al (2012) Oncomovies: cancer in cinema. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0923-7534(20)33959-4

Pavisic J, Chilton J, Walter G, Soh NL, Martin A (2014) Childhood cancer in the cinema: how the celluloid mirror reflects psychosocial care. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000195

García Sánchez JE, García Sánchez E (2004) [Antibiotics and cinema: The third man and Mercado prohibido]. Rev Esp Quimioter 17(3):223–225

Auwen A, Emmons M, Dehority W (2020) Portrayal of immunization in American cinema: 1925 to 2016. Clin Pediatr (Phila). https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819901004

Olivares Romero J (2010) Escenas en movimiento Los trastornos del movimiento en el cine. Neurologia. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0213-4853(10)70035-9

Biernoff S (2018) Theatres of surgery: the cultural pre-history of the face transplant. Wellcome Open Res. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14558.1

Yanicak A, Mohorn PL, Monterroyo P, Furgiuele G, Waddington L, Bookstaver PB (2015) Public perception of pharmacists: Film and television portrayals from 1970 to 2013. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 55(6):578–586. https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2015.15028

Virzi A, DiPasquale S, Signorelli MS, Bianchini O, Previti G, Palermo F, Aguglia E (2011) Movie portrayals of physicians and the doctor-patient relationship. J Cogn Behav Psychoth 6(2):475–485

Flores G (2002) Mad scientists, compassionate healers, and greedy egotists: the portrayal of physicians in the movies. J Natl Med Assoc 94(7):635–658

Cashman CR (2019) Golden ages and silver screens: the construction of the physician hero in 1930–1940 American Cinema. J Med Humanit. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-019-09554-0

Bernard F, Baucher G, Troude L, Fournier HD (2018) The surgeon in action: representations of neurosurgery in movies from the Frères Lumière to Today. World Neurosurgery. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.169

Hanewinkel R et al (2014) Portrayal of alcohol consumption in movies and drinking initiation in low-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3880

Hanewinkel R et al (2012) Alcohol consumption in movies and adolescent binge drinking in 6 European countries. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2809

Hanewinkel R, Tanski SE, Sargent JD (2007) Exposure to alcohol use in motion pictures and teen drinking in Germany. Int J Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym128

Sargent JD, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, Gibson J, Gibbons FX (2006) Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. J Stud Alcohol. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54

Morgenstern M et al (2013) Smoking in movies and adolescent smoking initiation: longitudinal study in six European countries. Am J Prev Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.037

Morgenstern M et al (2011) Smoking in movies and adolescent smoking: cross-cultural study in six European countries. Thorax. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200489

Charlesworth A, Glantz SA (2005) Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: a review. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0141

Stockman JA (2007) Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: a review. Yearb Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0084-3954(08)70268-9

Tynan MA, Polansky JR, Titus K, Atayeva R, Glantz SA (2017) Tobacco use in top-grossing movies — United States, 2010–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:681–686. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a1

Dillon KP, Bushman BJ (2017) Effects of exposure to gun violence in movies on children’s interest in real guns. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2229

Freedman M, Burke MG (2018) Seeing movies with guns piques kids’ interest in using them. Contemporary Pediatrics. Retrieved from [https://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/view/seeing-movies-guns-piques-kids-interest-using-them]

O’Hara RE, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Li Z, Sargent JD (2012) Greater exposure to sexual content in popular movies predicts earlier sexual debut and increased sexual risk taking. Psychol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611435529

Brown JD, L’Engle KL (2009) X-rated: sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with US early adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit media. Communic Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208326465

Wingood GM et al (2001) Exposure to X-rated movies and adolescents’ sexual and contraceptive-related attitudes and behaviors. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.5.1116

Lou C et al (2012) Media’s contribution to sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors for adolescents and young adults in Three Asian Cities. J Adolesc Heal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.009

O’Hara RE, Gibbons FX, Li Z, Gerrard M, Sargent JD (2013) Specificity of early movie effects on adolescent sexual behavior and alcohol use. Soc Sci Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.032

Calle SC, Evans JT (1994) Plastic surgery in the cinema, 1917–1993. Plast Reconstr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199402000-00035

Salgado CJ, Nugent A, Kuhn J (2018) Is there value to seeing a transgender fellowship-trained surgeon? Plast Reconstr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000004401

Magoon KL, LaQuaglia R, Yang R, Taylor JA, Nguyen PD (2020) The current state of gender-affirming surgery training in plastic surgery residency programs as reported by residency program directors. Plast Reconstr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000006426

Dubin SN et al (2018) Transgender health care: improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.s147183

Winter S et al (2016) Transgender people: health at the margins of society. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00683-8

Canner JK et al (2018) Temporal trends in gender-affirming surgery among transgender patients in the United States. JAMA Surg 153:609

Davy Z, Toze M (2018) What is gender dysphoria? A critical systematic narrative review. Transgender Heal. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2018.0014

Valashany BT, Janghorbani M (2018) Quality of life of men and women with gender identity disorder. Health Qual Life Outcomes 16:167

Gilman S. ‘The Jewish nose: are Jews white? Or, the history of the nose job’, in his book “The other in Jewish thought and history. Constructions of Jewish culture and identity”. Roudedge, New York, pp 169–193

Peiss K, Haiken E (1998) Venus Envy: a history of cosmetic surgery. J Am Hist. https://doi.org/10.2307/2567307

Preminger B (2001) The ‘Jewish nose’ and plastic surgery: origins and implications. J Am Med Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.17.2161-JMS1107-5-1

Larson DL (1997) A rhinoplasty tetralogy: corrective, secondary, congenital, reconstructive. Plast Reconstr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199706000-00049

Lam SM (2015) Asian blepharoplasty. In: Pearls and pitfalls in cosmetic oculoplastic surgery, 2nd edn. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 127–129

Lee CK, Ahn ST, Kim N (2013) Asian upper lid blepharoplasty surgery. Clin Plast Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2012.07.004

Ali AM, McVay CL (2016) Women in surgery: a history of adversity, resilience, and accomplishment. J Am Coll Surg 223:670–673

Plana NM et al (2018) The evolving presence of women in academic plastic surgery: a study of the past 40 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000004337

Silvestre J, Serletti JM, Chang B (2017) Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. plastic surgery trainees. J Surg Educ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.07.014

Parmeshwar N, Stuart ER, Reid CM, Oviedo P, Gosman AA (2019) Diversity in plastic surgery: trends in minority representation among applicants and residents. Plast Reconstr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000005354

Wu M, Wang J, Panayi AC (2020) Plastic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: the space, equipment, expertise approach. Aesthetic Surg J. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa136

Dhanda AK, Leverant E, Leshchuk K, Paskhover B (2020) A Google trends analysis of facial plastic surgery interest during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aesthetic Plast Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-020-01903-y

ISAPS (2016) The international study on aesthetic/cosmetic procedures performed in 2016. Annu ISAPS Int Surv. Retrieved from [https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/GlobalStatistics2016-1.pdf]

Kim YA, Chung HIC (2018) Side effect experiences of South Korean women in their twenties and thirties after facial plastic surgery. Int J Womens Health. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S163991

Gallos LK, Potiguar FQ, Andrade JS, Makse HA (2013) IMDB network revisited: unveiling fractal and modular properties from a typical small-world network. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066443

Wasserman M, Zeng XHT, Amaral LAN (2015) Cross-evaluation of metrics to estimate the significance of creative works. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1412198112

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not required.

Conflict of interest

Adriana C. Panayi, Yori Endo, Angel Flores Huidobro, Valentin Haug, Alexandra M. Panayi, and Dennis P. Orgill declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Panayi, A.C., Endo, Y., Huidobro, A.F. et al. Lights, camera, scalpel: a lookback at 100 years of plastic surgery on the silver screen. Eur J Plast Surg 44, 551–561 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-021-01834-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-021-01834-0