Abstract

Purpose

Rim lesions, characterised by a paramagnetic rim on susceptibility-based MRI, have been suggested to reflect chronic inflammatory demyelination in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. Here, we assess, through susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), the prevalence, longitudinal volume evolution and clinical associations of rim lesions in subjects with early relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS).

Methods

Subjects (n = 44) with recently diagnosed RRMS underwent 3 T MRI at baseline (M0) and 1 year (M12) as part of a multi-centre study. SWI was acquired at M12 using a 3D segmented gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence. Rim lesions identified on SWI were manually segmented on FLAIR images at both time points for volumetric analysis.

Results

Twelve subjects (27%) had at least one rim lesion at M12. A linear mixed-effects model, with ‘subject’ as a random factor, revealed mixed evidence for the difference in longitudinal volume change between rim lesions and non-rim lesions (p = 0.0350 and p = 0.0556 for subjects with and without rim lesions, respectively). All 25 rim lesions identified showed T1-weighted hypointense signal. Subjects with and without rim lesions did not differ significantly with respect to age, disease duration or clinical measures of disability (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

We demonstrate that rim lesions are detectable in early-stage RRMS on 3 T MRI across multiple centres, although their relationship to lesion enlargement is equivocal in this small cohort. Identification of SWI rims was subjective. Agreed criteria for defining rim lesions and their further validation as a biomarker of chronic inflammation are required for translation of SWI into routine MS clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurological condition affecting over 2 million individuals worldwide [1]. MS is an immune-mediated disease characterised by inflammation, demyelination, neurodegeneration and remyelination. Most patients initially diagnosed with relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS), the most common form of MS, experience two distinct clinical phases, reflecting a dominant role for distinct pathological processes. Inflammation drives activity during the relapsing–remitting stage, with neurodegeneration being predominant in progressive MS characterised by accumulating disability [2].

Whilst the reference standard for pathological characterisation is histological analysis of biopsy or, more commonly, autopsy material [3,4,5], recent progress in imaging raises the possibility of non-invasive and longitudinal measurement and ‘pathological’ characterisation of lesions. For instance, susceptibility-based magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides support for the paramagnetic properties of certain MS lesions [6,7,8]. These lesions may be identified on susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) by a hyperintense core surrounded by a partial or complete rim of hypointense signal. The high tissue susceptibility observed at the edge of rim lesions has been histologically shown to correspond to iron deposition and a high density of activated myeloid cells, suggesting the involvement of iron-laden macrophages/microglia [9,10,11]. The origin of iron in myeloid cells is still unclear, although damage to myelin and oligodendrocytes may result in the release of iron into the interstitium and subsequent engulfment by macrophages and microglia [12].

Rim lesions have been found to coincide with regions of hypointensity on T1-weighted spin-echo sequences, also known as ‘T1 black holes’, as well as with hypointensity on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), both of which are associated with substantial tissue damage [13, 14]. Rim lesions appear to experience significant growth over time compared with lesions without rims, supporting histological evidence that they could reflect a state of chronic inflammatory demyelination due to macrophage/microglial activity [10, 11]. Iron-laden rims are also rarely found around remyelinated plaques [10]. Against this background of combined pathological and radiological evidence, rim lesions have been argued to represent a potential marker of chronic or low-level inflammation in MS. Rim lesions are also not present in ‘mimic’ conditions such as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), Susac syndrome and cerebrovascular disease [15,16,17,18,19,20].

The clinical correlates of rim lesions are unclear, as they are observed in clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) as well as RRMS and progressive disease [21,22,23]. However, recent results suggest that non-gadolinium enhancing rim lesions, also known as ‘chronic active lesions’, are linked to a more severe disease phenotype [11]. The majority of rim lesion studies in MS have been single-centre and focussed on later stage disease [23]. In this multi-centre study, we sought to evaluate the prevalence of rim lesions and their relationship with ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ in recently diagnosed RRMS patients using SWI at 3 T.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects (n = 44) were recruited from a multi-centre prospective observational cohort study for people recently diagnosed with RRMS. The inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of RRMS according to 2010 McDonald criteria [24], within 6 months of diagnosis at baseline assessment (M0), age ≥ 18 years at baseline assessment, disease-modifying therapy (DMT) not prescribed prior to baseline assessment, no contraindication to MR brain imaging. Participants attend two clinic visits, approximately 12 months apart for clinical examinations, brain MR imaging and laboratory tests. SWI was carried out at the 1-year time point (M12).

Clinical assessment

Motor and cognitive disability of participants are assessed via various measures including the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), the Timed 25-Foot Walk Test (T25FWT), the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT), the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) and the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) score. Plasma neurofilament (NfL) levels are obtained from participants at M0 using a single-molecule ELISA. The assay is run on a 4-Plex "A" Kits Quanterix and Simoa SR-XTM benchtop instrument.

MRI acquisition

MRI was performed at three research sites on Prisma 3 T MRI systems (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, De) using either a 32-channel or 20-channel receive head coil and with a maximum gradient strength of 80 mT/m. The brain imaging protocol for both timepoints (M0 and M12) includes 3D volume T1-weighted, 2D axial PD/T2-weighted (dual echo), 3D volume FLAIR and 2D axial FLAIR sequences (please see Supplementary Table S1 for detailed acquisition parameters). SWI was acquired at M12; magnitude, phase and susceptibility-weighted images were acquired using a 3D segmented gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence (repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 64/35 ms, flip angle = 10 degrees, voxel size = 0.65 mm isotropic, acquisition time = 7:08 m:ss) [25].

Data analysis

Identification of rim lesions

Following conversion of DICOM images to NIfTI format using the dcm2niix tool [26], rigid body registration (6 degrees of freedom) of follow-up 2D FLAIR to SWI images was performed using the FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (FLIRT) software [27, 28]. Hyperintense white matter lesions (WMLs) were identified on registered 2D FLAIR and assessed in all three anatomical planes on corresponding SWI images using ITK-SNAP Version 3.8.0 [29]. Rim lesions were defined as lesions that were hyperintense on FLAIR and were characterised on SWI by a hyperintense core partially or completely surrounded by a hypointense rim. Possible rim lesions were identified by one trained observer and reviewed by a senior neuroradiologist. SWI images were also independently assessed for rim lesions by a second neuroradiologist, after which the final rim lesion count for each subject was determined by consensus of all three raters. Lesions with a minimum diameter of less than 3 mm were deemed too small to be reliably assessed for the presence of a rim and were excluded. Lesions located near a high density of veins or considerable juxtacortical signal heterogeneity could not be reliably evaluated and were therefore not considered for inclusion.

Identification of ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ and ‘FLAIR-hypointense core lesions’

After rim lesion identification, T1-weighted images were registered to SWI images. SWI rim lesions were assessed on corresponding registered T1-weighted and 2D FLAIR images and classified as ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ and ‘FLAIR-hypointense core lesions’, respectively. ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ were defined as lesions that were hyperintense on FLAIR and corresponded to a hypointense region on T1-weighted images. ‘FLAIR-hypointense core lesions’ were defined as lesions hyperintense on FLAIR, but demonstrating regions of hypointensity or isointensity relative to extralesional white matter, typically in the lesion core. Unregistered T1-weighted images at follow-up were also assessed to determine the total ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ count. Lesions with a minimum diameter of less than 3 mm were excluded, as these could not be reliably assessed. The ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ count was performed twice on 10 randomly selected subjects in order to calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). T2-weighted WML volume was estimated on 3D FLAIR as a percentage of intracranial volume (ICV).

Longitudinal volume analysis

Individual rim lesions were manually segmented on unregistered 3D FLAIR images at both time points, and volumes computed using ITK-SNAP Version 3.8.0 [29]. All rim lesions were included in the longitudinal volume analysis. Distinct non-confluent lesions without rims in (a) subjects with rim lesions and (b) subjects without rim lesions were chosen as controls. Where possible, an equal number of rim and non-rim lesions were selected in each subject to allow for within-participant variability. Lesions that were previously excluded as they could not be reliably assessed for the presence of a rim were not eligible to act as control. Manual segmentation was performed twice on 10 randomly selected lesions (either rim or non-rim lesion) in order to determine the ICC.

Statistical analysis

Study participants were first classified into those with rim lesions and those without rim lesions at follow-up. Differences between the two groups with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed via statistical tests such as the Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test according to variable type. Adjustment for multiple comparisons was not performed for demographic and clinical comparisons due to the exploratory nature of the study, although exact uncorrected p-values are reported. The relationship between rim lesion count and both ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ count and WML volume was assessed by Spearman’s correlation. Differences in lesion volume between baseline and follow-up were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with post hoc multiple comparisons using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni adjustment. A linear mixed-effects model was used to assess differences in longitudinal volume change amongst lesion groups, with ‘lesion type’ as a fixed effect and ‘subject’ as a random effect. ICC estimates were calculated based on a single rating, absolute agreement, and two-way mixed-effects model. All statistical analyses were performed using R Version 3.6.3.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Forty-four subjects were included, all of whom were diagnosed with RRMS (Table 1). Seventy-five percent of the cohort was female. Mean age at the time of SWI was 42.6 years (SD = 12.8), while mean times from diagnosis and onset of symptoms to SWI were 494 days (SD = 67) and 1781 days (SD = 1840), respectively. Mean duration of follow-up was 415 days (SD = 50). Median follow-up and baseline EDSS scores were 3.0 (1.0–6.0) and 2.25 (0–6.0), respectively. Median scores at follow-up for other measures of clinical disability including T25FWT, PASAT, SDMT and MSFC are provided in Table 1. Twenty-eight out of 42 subjects (data not available for two subjects) were on DMT at follow-up, with two subjects being on more than one drug. Mean baseline plasma NfL levels were 8.4 pg/mL (SD = 5.2). Individual subject characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Rim lesions

Twelve subjects (27%) demonstrated at least one rim lesion. A total of 25 rim lesions were identified, with the rim lesion count per subject ranging from 1 to 3, except in one subject in which 8 rim lesions were identified (mean [SD] for rim lesion count = 0.6 [1.4]). Rim lesions were predominantly observed supratentorially, with only one infratentorial rim lesion being identified. Examples of SWI rim lesions and corresponding 2D FLAIR images are shown in Fig. 1. Although concordant results were obtained for 9 out of 12 subjects with rim lesions following independent review by the two groups of raters, discussion amongst all three raters was required to reach a consensus regarding the rim lesion count in the remaining 3 subjects.

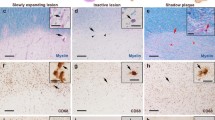

‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ and ‘FLAIR-hypointense core lesions’

Assessment of registered T1-weighted images and SWI images revealed that all 25 rim lesions (100%) corresponded to ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’. Ten rim lesions (40%) could further be classified as ‘FLAIR-hypointense core lesions’ on FLAIR images. Figure 2 shows an example of a rim lesion that on T1-weighted image demonstrated hypointensity, and on 2D FLAIR appeared as a hyperintense lesion exhibiting intralesional isointensity. A total of 874 ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ were observed in all 44 subjects (Mean [SD] for ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ count = 20 [18]). All subjects had at least one ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ (Range = 2–116). Rim lesions constituted only a small proportion of total ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ (2.9%). No significant correlation was observed between rim lesion count and ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ count (Spearman’s rho = 0.271, p value = 0.0752). Estimated ICC with 95% confidence intervals for ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ count was 0.989 (0.950–0.997). The correlation between rim lesion count and WML volume was non-significant (Spearman’s rho = 0.118, p value = 0.4474).

T1 and FLAIR appearance of an SWI rim lesion. All rim lesions observed in our MS cohort, including this white matter lesion (indicated by red arrow) exhibited T1 hypointensity. The lesion shown above is one of ten rim lesions that on FLAIR also appeared hyperintense with a core isointense or in this case, hypointense, relative to extralesional white matter

Assessing group differences

No significant differences were observed at M12 between subjects with rim lesions and subjects without rim lesions with regard to age, disease duration, DMT status, EDSS or any other measures of clinical disability including T25FWT, PASAT, SDMT or MSFC (Table 1). Baseline plasma NfL levels also did not differ between the two groups. Female subjects appeared to constitute a greater proportion of subjects without rim lesions than of subjects with rim lesions (p = 0.045).

Longitudinal volume analysis

Twenty-five rim lesions, 26 non-rim lesions in subjects with rim lesions and 26 non-rim lesions in subjects without rim lesions were selected for longitudinal volume analysis (please see Supplementary Table S3 for more information on lesion selection). Rim lesions were significantly larger than non-rim lesions both in subjects with and without rim lesions both at baseline (mean [SD]/mm3 = 489 [253], 152 [108] and 203 [146], respectively; p < 0.001) and at follow-up (mean [SD]/mm3 = 506 [263], 138 [102] and 165 [103], respectively; p < 0.001). Non-rim lesions in subjects with and without rim lesions were not significantly different in size both at baseline and follow-up (p = 0.806 and p = 0.810, respectively). Estimated ICC with 95% confidence intervals for volume determination by manual segmentation was 0.988 (0.954–0.997).

We found mixed evidence for the difference in 1-year percentage longitudinal volume change between rim lesions and non-rim lesions (p = 0.0350 and p = 0.0556 for subjects with and without rim lesions, respectively). Percentage changes in lesion volumes are shown in Fig. 3. We also arbitrarily categorised lesions, taking into account the margin of error during manual segmentation, as shrinking (x < − 5%), steady (− 5% < x < 5%) or enlarging (x > 5%). Although shrinking, steady and enlarging subtypes were observed in all three lesion groups, enlarging lesions constituted a greater proportion of rim lesions (60%) compared to non-rim lesions (27% for both subjects with and without rim lesions). A breakdown of lesion groups into the different subtypes is available from the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

In this study involving a cohort of recently diagnosed subjects with RRMS, we observed a rim lesion prevalence of 27%, with 12 out of 44 subjects having at least one. This accords with other recently published data [23] and suggests that rim lesions are a feature of early MS, although less common than in patients with longer disease durations. Our study adds to the growing body of literature on SWI at 3 T [11, 22, 23, 30, 31] and furthermore demonstrates the feasibility of multi-centre acquisition, albeit using a single manufacturer MRI platform in this instance. Further studies across different manufacturer platforms will be necessary for validation in large cohort studies towards future clinical implementation.

Notably, all 25 of the rim lesions identified in our study corresponded to ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’. Rim lesions comprised only a very small proportion of the overall number of ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’, however, and no significant correlation was observed between rim lesion count and ‘T1-w hypointense lesion’ count. Pathological correlation studies have shown ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ characterised on spin-echo sequences as ‘T1 black holes’ to be associated with substantial tissue damage characterised by oedema, demyelination and axonal loss [32, 33]. ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’ detected on volumetric spoiled gradient-recalled echo (SPGR), as used in the current and a growing number of other studies, have been less well characterised pathologically, but are likely to show similar correlations with underlying parenchymal damage.

A smaller number of rim lesions corresponded to ‘FLAIR-hypointense core lesions’, which have also been described in the literature [34], and are likely to represent a subset of ‘T1-w hypointense lesions’. Our data do not allow any firm conclusions to be drawn regarding the nature of these and their relationship to chronic low-grade inflammation.

Because of their apparent specificity for MS, the presence of rim lesions has been suggested as potentially useful in the radiological differential diagnosis of other neurological conditions whose imaging appearances may overlap with MS [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Although we have demonstrated their presence in early MS, the low prevalence would in practice limit diagnostic sensitivity.

In line with previous findings, we were unable to demonstrate strong evidence for a difference in the 1-year longitudinal volume evolution between rim lesions and non-rim lesions, [10, 13], although potential errors in our volumetric measurement due to manual segmentation of poorly defined individual lesions may limit the sensitivity of our analysis. We nevertheless observed that rim lesions were more commonly enlarging, in contrast to ‘shrinking’ non-rim lesions. Our finding of similar volume changes in non-rim lesions in subjects who had one or more rim lesions and those who had none may indicate a more localised inflammatory process in rim lesions.

A number of studies suggest that a subset of rim lesions may initially shrink [6, 10, 11]. While no clear relationship has been established between the presence of a paramagnetic rim and lesion growth measured over short intervals, recent findings suggest that differences in lesion volume evolution become more pronounced over longer time periods [10, 11]. Although it remains unclear whether rim lesions and slowly enlarging lesions define the same lesion subgroup, an overlap between the two is likely.

Our study focuses on patients with recently diagnosed RRMS, and the observation of overall shrinkage of WMLs may well reflect partial resolution of acutely swollen lesions over the year following the acute inflammatory episodes which originally lead to diagnosis. The early stage in disease course may also help to explain the lack of association observed between the presence of rim lesions and clinical disability, as substantial variation in disability between patients often only becomes apparent over several years. The lack of significant association detected between rim lesions and elevated plasma neurofilament levels may also be influenced by the modest prevalence of both in early disease, and the confound that the two measures were made a year apart.

Several factors can confound the assessment of paramagnetic phase rims, including high venous density, regions of juxtacortical signal heterogeneity and the presence of susceptibility or motion-related artefacts. While rims were more commonly observed across larger lesions, we were unable to assess hypointensity around the edge of smaller lesions reliably, which may in part be due to lower signal-to-noise ratio and contrast resolution at 3 T compared with ultra-high field 7 T. This challenge is compounded by the fact that lesions are sometimes only partially bordered by a rim of decreased signal on SWI. The difficulty in confidently classifying rim lesions is reflected in our limited inter-rater concordance in rim lesion count and accords with previous observations regarding the current lack of standardised methods for evaluating the presence of a paramagnetic phase rim, and that familiarity with susceptibility-based MRI may be necessary for guiding rim lesion assessment [30].

Our study has several limitations. First, the low prevalence of rim lesions in our patient cohort meant that relatively few lesions could be included in our analysis. A further significant limitation is that contrast-enhanced images were not acquired; as a result, ‘chronic active lesions’ that have been defined on imaging as non-gadolinium enhancing lesions with a paramagnetic rim could not be identified in our study. Active inflammatory lesions could also not be evaluated. We further recognise that SWI was only performed at a single 1-year timepoint (M12); the longitudinal evolution of the paramagnetic rim sign could therefore not be assessed and limits correlative measurements with neurofilament levels which were only sampled at baseline (M0). Future efforts will focus on collecting longitudinal SWI in the same cohort.

Conclusion

Various lines of evidence indicate that rim lesions identified with SWI may reflect chronic inflammation in MS patients. We have demonstrated that rim lesions are also a feature of subjects with early MS using a 3 T SWI in a multi-centre context, and our data suggest a possible relationship with lesion growth and shrinkage. The integration of SWI rim lesions in routine MS imaging practice will require further studies in larger cohorts across the disease course and consensus on a standardised approach to their assessment.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Change history

05 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-021-02844-2

Abbreviations

- CIS:

-

Clinically isolated syndrome

- DICOM:

-

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine

- DMT:

-

Disease-modifying therapy

- EDSS:

-

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- FOV:

-

Field of view

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- ICV:

-

Intracranial volume

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- MSFC:

-

Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite

- NIfTI:

-

Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative

- NfL:

-

Neurofilament

- NMOSD:

-

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder

- PASAT:

-

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test

- RIS:

-

Radiologically isolated syndrome

- RRMS:

-

Relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis

- SDMT:

-

Symbol Digit Modalities Test

- SPGR:

-

Spoiled gradient-recalled echo

- SWI:

-

Susceptibility-weighted imaging;

- T25FWT:

-

Timed 25-Foot Walk Test

- TE:

-

Echo time

- TI:

-

Inversion time

- TR:

-

Repetition time

- WML:

-

White matter lesion

References

Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O (2018) Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 391(10130):1622–1636

Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA (2018) Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 378(2):169–180

Kuhlmann T, Ludwin S, Prat A, Antel J, Bruck W, Lassmann H (2017) An updated histological classification system for multiple sclerosis lesions. Acta Neuropathol 133(1):13–24

Metz I, Weigand SD, Popescu BF, Frischer JM, Parisi JE, Guo Y et al (2014) Pathologic heterogeneity persists in early active multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol 75(5):728–738

Lucchinetti C, Bruck W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H (2000) Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol 47(6):707–717

Absinta M, Sati P, Reich DS (2016) Advanced MRI and staging of multiple sclerosis lesions. Nat Rev Neurol 12(6):358–368

Filippi M, Bruck W, Chard D, Fazekas F, Geurts JJG, Enzinger C et al (2019) Association between pathological and MRI findings in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 18(2):198–210

Matthews PM (2019) Chronic inflammation in multiple sclerosis - seeing what was always there. Nat Rev Neurol 15(10):582–593

Bagnato F, Hametner S, Yao B, van Gelderen P, Merkle H, Cantor FK et al (2011) Tracking iron in multiple sclerosis: a combined imaging and histopathological study at 7 Tesla. Brain 134:3599–3612

Dal-Bianco A, Grabner G, Kronnerwetter C, Weber M, Hoftberger R, Berger T et al (2017) Slow expansion of multiple sclerosis iron rim lesions: pathology and 7 T magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Neuropathol 133(1):25–42

Absinta M, Sati P, Masuzzo F, Nair G, Sethi V, Kolb H et al (2019) Association of chronic active multiple sclerosis lesions with disability in vivo. Jama Neurol 76(12):1474–1483

Gillen KM, Mubarak M, Nguyen TD, Pitt D (2018) Significance and in vivo detection of iron-laden microglia in white matter multiple sclerosis lesions. Front Immunol 9:255

Absinta M, Sati P, Schindler M, Leibovitch EC, Ohayon J, Wu T et al (2016) Persistent 7-tesla phase rim predicts poor outcome in new multiple sclerosis patient lesions. J Clin Invest 126(7):2597–2609

Yao B, Ikonomidou VN, Cantor FK, Ohayon JM, Duyn J, Bagnato F (2015) Heterogeneity of Multiple Sclerosis White Matter Lesions Detected With T2*-Weighted Imaging at 7.0 Tesla. J Neuroimaging 25(5):799–806

Chawla S, Kister I, Wuerfel J, Brisset JC, Liu S, Sinnecker T et al (2016) Iron and non-iron-related characteristics of multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica lesions at 7T MRI. Am J Neuroradiol 37(7):1223–1230

Kilsdonk ID, Wattjes MP, Lopez-Soriano A, Kuijer JPA, de Jong MC, de Graaf WL et al (2014) Improved differentiation between MS and vascular brain lesions using FLAIR* at 7 Tesla. Eur Radiol 24(4):841–849

Sinnecker T, Dorr J, Pfueller CF, Harms L, Ruprecht K, Jarius S et al (2012) Distinct lesion morphology at 7-T MRI differentiates neuromyelitis optica from multiple sclerosis. Neurology 79(7):708–714

Sinnecker T, Schumacher S, Mueller K, Pache F, Dusek P, Harms L et al (2016) MRI phase changes in multiple sclerosis vs neuromyelitis optica lesions at 7T. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 3(4):e259

Wuerfel J, Sinnecker T, Ringelstein EB, Jarius S, Schwindt W, Niendorf T et al (2012) Lesion morphology at 7 Tesla MRI differentiates Susac syndrome from multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 18(11):1592–1599

Maggi P, Sati P, Nair G, Cortese ICM, Jacobson S, Smith BR et al (2020) Paramagnetic rim lesions are specific to multiple sclerosis: an international multicenter 3t mri study. Ann Neurol 88(5):1034–1042

Suthiphosuwan S, Sati P, Absinta M, Guenette M, Reich DS, Bharatha A et al (2020) Paramagnetic rim sign in radiologically isolated syndrome. JAMA Neurol 77(5):653–655

Clarke MA, Pareto D, Pessini-Ferreira L, Arrambide G, Alberich M, Crescenzo F et al (2020) Value of 3T susceptibility-weighted imaging in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 41(6):1001–1008

Blindenbacher N, Brunner E, Asseyer S, Scheel M, Siebert N, Rasche L et al (2020) Evaluation of the “ring sign” and the “core sign” as a magnetic resonance imaging marker of disease activity and progression in clinically isolated syndrome and early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 6(1):2055217320915480

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M et al (2011) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 69(2):292–302

Sati P, Patil S, Inati S, Wang WT, Derbyshire JA, Krueger G et al (2017) Rapid MR susceptibility imaging of the brain using segmented 3d echo-planar imaging (3d EPI) and its clinical applications. Magnetom FLASH 68:26–32

Li X, Morgan PS, Ashburner J, Smith J, Rorden C (2016) The first step for neuroimaging data analysis: DICOM to NIfTI conversion. J Neurosci Methods 264:47–56

Jenkinson M, Smith S (2001) A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 5(2):143–156

Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S (2002) Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17(2):825–841

Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC et al (2006) User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 31(3):1116–1128

Absinta M, Sati P, Fechner A, Schindler MK, Nair G, Reich DS (2018) Identification of chronic active multiple sclerosis lesions on 3T MRI. Am J Neuroradiol 39(7):1233–1238

Eisele P, Fischer K, Szabo K, Platten M, Gass A (2019) Characterization of contrast-enhancing and non-contrastenhancing multiple sclerosis lesions using susceptibility-weighted imaging. Front Neurol 10:1082

Bagnato F, Jeffries N, Richert ND, Stone RD, Ohayon JM, McFarland HF et al (2003) Evolution of T1 black holes in patients with multiple sclerosis imaged monthly for 4 years. Brain 126(Pt 8):1782–1789

Thaler C, Faizy TD, Sedlacik J, Holst B, Sturner K, Heesen C et al (2017) T1 Recovery is predominantly found in black holes and is associated with clinical improvement in patients with multiple sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38(2):264–269

Rovaris M, Comi G, Rocca MA, Cercignani M, Colombo B, Santuccio G et al (1999) Relevance of hypointense lesions on fast fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR images as a marker of disease severity in cases of multiple sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 20(5):813–820

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all FutureMS participants who have made this study possible.

Funding

The SWI substudy was funded by an unrestricted grant from Biogen Idec Ltd. FutureMS is hosted by Precision Medicine Scotland Innovation Centre (PMS-IC) and funded by a grant from the Scottish Funding Council to PMS-IC and Biogen Idec Ltd Insurance (combined funding under reference Exemplar SMS_IC010). The University 3 T MRI Research scanner in RIE is funded by the Wellcome Trust (104916/Z/14/Z), Dunhill Trust (R380R/1114), Edinburgh and Lothians Health Foundation (2012/17), Muir Maxwell Research Fund, Edinburgh Imaging, and University of Edinburgh. Additional funding for authors came from the MS Society Edinburgh Centre for MS Research — grant reference 133 (RM), the NHS Lothian Research and Development Office (MJT), Chief Scientist Office — SPRINT MND/MS program (ENY), Anne Rowling Clinic & Glasgow MS Clinical Research Facility (SJM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The study received ethical approval from the South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee 02 under reference 15/SS/0233 and is being conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and ICH guidelines on good clinical practice.

Informed consent

All participants receive a patient information sheet and appropriate explanation about the study and provide written informed consent prior to study enrolment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Originally, the first author's name has been erroneously published, with the surname appearing as Kwong instead of Ng Kee Kwong.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ng Kee Kwong, K.C., Mollison, D., Meijboom, R. et al. Rim lesions are demonstrated in early relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis using 3 T-based susceptibility-weighted imaging in a multi-institutional setting. Neuroradiology 64, 109–117 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-021-02768-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-021-02768-x