Abstract

Purpose

This review aimed to determine the prevalence, causes and risk factors of medicine-related problems (MRPs) in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Methods

Eight online databases were searched up to 30 September 2018 with no start date. Appropriate Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tools were used to assess the quality of included studies.

Results

An overall 16 quantitative and 11 qualitative studies were included in the review. Methodological quality of the included studies was variable. Mean frequency of MRPs reported in the quantitative studies ranged from 14 to 23.4%. The most frequent causes of MRPs included drug interactions, inappropriate dosing and use of contraindicated drugs. The qualitative analysis identified three themes: patient-related factors, healthcare professionals’ related factors and stigma associated with liver cirrhosis.

Conclusion

MRPs were found to be prevalent in patients with liver cirrhosis. Factors contributing to MRPs in liver cirrhosis were not limited to medicines’ effects and interactions but included healthcare systems and patients. Therefore, management of liver cirrhosis should not be limited to providing an effective medicine therapy and should take into account the patients’ behaviour towards the condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is a major chronic disease that is associated with high morbidity and mortality [1]. In the USA, the incidence of liver cirrhosis was around 0.27% corresponding to approximately 634,000 adults [2]. The Global Burden of Disease reported that more than one million people died worldwide due to liver cirrhosis in 2010 compared with 676,000 deaths in 1980 [3]. Patients affected by liver cirrhosis are at an increased risk of developing multiple complications and consequently have reduced life expectancy [4]. For instance, ascites is one of the most common complications of liver cirrhosis [5] and is responsible for 15% of deaths in patients with liver cirrhosis within 1 year of their diagnosis [6]. Similarly, a recent cohort study on hospital readmissions in patients diagnosed with liver cirrhosis suggests that about 13% of the admissions within 30 days were caused by complications of the disease [7].

It is also important to highlight that the drug therapy in liver cirrhosis is complex due to the pathophysiological changes associated with the disease that alter the pharmacokinetics of drugs [8, 9]. For instance, the reduced albumin synthesis in liver cirrhosis [10] can increase the risk of potential drug toxicity of protein-bound drugs due to their increased plasma concentration. Similarly, the metabolic capacity is also compromised in liver cirrhosis due to the reduction of metabolising enzymes such as CYP450 in the liver and hence impairment in hepatic blood flow [11]. Thus, patients with liver cirrhosis are more sensitive to medicines and their side effects with evidence suggesting that around 30% of patients with liver cirrhosis exhibit adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and have a high risk of hospitalisation [12]. These findings indicate that patients with liver cirrhosis require close monitoring and dose adjustment to ensure rational use of medicines and to avoid the risk of ADRs and other medicine-related problems (MRPs).

A MRP is defined as “an event or a circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with the desired health outcome” [13]. The other major categories of MRPs besides ADRs include adverse drug events (ADEs) and medication errors (MEs) [14]. In addition to making an appropriate selection of drug therapy, it is also important to understand other factors that might influence the rational use of medicines in a complex disease such as liver cirrhosis. Some of these factors include patient knowledge and understanding about the disease and its management [15]. To the authors’ knowledge, no review to date has been conducted to determine the underlying causes and risk factors of MRPs in patients with liver cirrhosis. This review, therefore, aims to systematically investigate the prevalence, causes and risk factors of MRPs in cirrhotic patients and to explore factors influencing the medicine use from both patients and healthcare providers’ perspectives.

Methods

As this review included both quantitative and qualitative studies which investigated medicine use and MRPs in patients with cirrhosis, the pragmatic approach was found to be the most appropriate philosophical paradigm that rationalises the analysis process and hence answers the objectives of this review [16]. The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the recommendation of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [17].

Search strategy

Eight online databases (PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, The British Library, PsycInfo and Google Scholar) were systematically and comprehensively searched from inception to September 2018. Search terms included medicine (drug/medication)–related problems, medicine (drug/medication) use, liver (hepatic) cirrhosis, chronic liver diseases, attitude, knowledge, adherence and non-adherence (Appendix 1). Additional relevant terms were also handpicked from the literature during the review. Boolean operators (OR, AND, NOT) were utilised to combine concepts and refine the width and depth of search to capture available evidence. Grey literature was searched using Open Grey and EBSCO. Furthermore, scooping in Google and a manual search of references cited in retrieved articles were performed by the reviewer (AA) to identify relevant studies. Reference lists of retrieved articles and relevant review articles were manually examined for further relevant studies.

List of definitions

An adverse drug event (ADE) is defined as “an injury resulting from the use of a drug” [18]. An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is “an appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction, resulting from an intervention related to the use of a medicinal product” [18]. A cause of an MRP is defined as “the action (or lack of action) that leads up to the occurrence of a potential or real problem. There may be more than one cause for a problem” [14]. Comorbidities are defined as chronic illnesses or diseases which require long-term treatment [19] and coexist alongside the main diagnosis. Medicine adherence is defined as the extent to which the patient’s drug-taking behaviour (in terms of taking medication) coincides with the agreed recommendation [20]. A medication error (ME) is defined as “failure in the treatment process that leads to, or has the potential to lead to, harm to the patient” [21]. An MRP is defined as an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes [14, 22]. Polypharmacy is defined as the use of five or more medications [23]. A risk factor is an action (or lack of action) that facilitates the occurrence of an MRP [24]. The rational use of drugs comprises “providing patients with the right medications in correct doses that are appropriate for their individual indications, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost” [25].

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

The review included both quantitative and qualitative studies published in English language and in peer-reviewed journals. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they included patients (≥ 18 years old) diagnosed with liver cirrhosis or chronic liver diseases and investigated the frequency and causes of MRPs in cirrhotic patients. Qualitative studies reporting beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and perception of patients/healthcare professionals towards liver cirrhosis and its treatment were also included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if their main focus was liver diseases other than liver cirrhosis such as hepatitis, encephalopathy or hepatic carcinoma. Review articles, editorials and commentaries were not included in the review.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer (AA) and was independently verified by a second reviewer (AH). Any differences were resolved by the involvement of a third reviewer (EC). Items extracted from the studies included study title, author name, year of study, country, study design, sample size and results.

Data analysis was conducted over two stages where two methods were applied to the findings of the review being textual narrative analysis (for quantitative data) and thematic analysis (for qualitative data).

The textual narrative approach encompassed recording the aim, characteristics, quality and outcomes (whether ADEs, ADRs, MEs or MRPs) for each study in order to draw conclusion from the findings. The reported prevalence of ADRs and MEs were grouped as two categories under MRPs. Due to the heterogeneity among the studies, it was not possible to report the means, and only prevalence per study was calculated. Furthermore, the medicines reported in the included studies were grouped into main medicine classes including analgesics (paracetamol, opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)), antimicrobials, diuretics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and sedatives.

Data from the qualitative studies were synthesised using thematic synthesis technique reported by Thomas and Harden [26]. The synthesis was conducted in three phases: phase 1: line-by-line coding of the findings of the primary studies, phase 2: developing sub-themes through organising the codes and phase 3: generating themes. This approach was then repeated, and studies were reread to ensure transparent integration of all concepts related to our research question and objectives. The naming of themes and sub-themes was either as original studies or under different names, where it was conceptually appropriate. The emerged themes offered an interpretation to address our review’s objectives and go beyond the content of the results of the primary studies [26]. Quotations from the articles were used to illustrate the identified themes (Table 3).

Quality assessment

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools were used to assess the quality of both quantitative and qualitative studies [34]. Since there is no CASP checklist available for cross-sectional studies, the Quality of Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies quality assessment tool (Appendix 2) was used to assess the quality of the included cross-sectional studies [35].

The items assessed for the quality of qualitative studies included study aims, methods, validity and reliability of data collection and appropriateness of the study design. While for the quantitative studies, the assessment items included appropriateness of the study design, the risk of bias, statistical issues and data generalisability.

The included studies were categorised based on a grading criteria that took into account the number of questions that were fulfilled based on the above-mentioned tools: that is, high quality (***) for a score of 7–10 points, medium quality (**) if scored 4–6 points and low quality (*) if scored 0–3 points. Although the low-quality studies were not excluded, their findings were interpreted with caution.

Results

Study selection

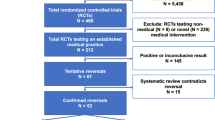

The initial search yielded 503 studies. A further seven studies were identified through manual searches of reference lists bringing the total to 510 studies (Fig. 1). Three hundred sixty-one studies were left after removal of duplicates and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of these, 102 studies were excluded after reviewing abstracts and titles. The remaining 47 studies were further assessed, and another 20 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Twenty-seven studies were included in the review. Of these, 16 were quantitative and 11 were qualitative studies.

Quantitative studies

A total of 16 quantitative studies with 5636 participants were included in the review [15, 27,28,29,30, 32, 33, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Of these 16 studies, three were conducted in Australia [36,37,38] and the USA [15, 39, 40], two each in Chile [41, 42] and Indonesia [33, 43], and one each from Switzerland [27], India [28], UK [30], Pakistan [29] and Netherlands [32]. All included studies used an observational study design (Table 1).

Prevalence of MRPs

Nine studies reported the incidence of the MRPs [12, 27, 29, 32, 33, 38, 41,42,43]. Seven of the nine studies reported the incidence using total patients as a denominator. The mean prevalence of MRPs reported in these studies ranged from 4.21 to 38.4%. The remaining two studies used the total number of prescriptions as a denominator with the mean prevalence ranging from 8.33 to 22%. Owing to the heterogeneity between the methods of measuring MRPs, it was not possible to calculate the mean prevalence across all nine studies. Moreover, definitions of MRPs varied among the included studies which made it difficult to conduct meta-analysis.

The most common category of MRPs reported in the studies was ADRs. It was reported in six out of the nine included studies, while the ME was the other common category of MRP reported in three retrospective studies. No study reported data on ADEs.

Causes and risk factors of MRPs

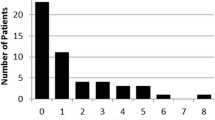

Causes in the evaluated studies were actions that directly triggered the occurrence of an MRP. Seven studies reported the causes of MRPs [12, 27, 29, 32, 33, 38, 41]. The reported causes of MRPs included drug-drug interactions [12, 27, 29, 33], inappropriate dosing [12, 29, 32, 41], contraindications [32, 38] and inappropriate choice of drug therapy [29]. In addition, risk factors contributed to MRPs’ incidence without having a direct causal relationship with MRPs. Polypharmacy was the most commonly reported risk factor for liver cirrhosis [27, 41, 42] where MRPs were more prevalent in patients taking a median of seven to nine medicines. This was followed by associated comorbidities such as ascites, portal hypertension and prior hepatic encephalopathy [27, 42]. Moreover, the severity of the disease [12, 42] and the longer duration of hospital stay (more than 12 days) [41, 42] further contributed to MRPs. Other reported risk factors included old age (range 39–62 years) [27] and impaired renal function (renal dysfunction considered when blood urea nitrogen was above 25 mg/100 ml and/or creatinine clearance was below 80 ml/min) [27].

Medicine classes

Nine studies reported data on medicine classes suspected to be associated with DRPs [12, 27, 29, 32, 33, 38, 41,42,43]. Diuretics including furosemide and spironolactone were the most commonly reported medicines attributed to MRPs [12, 25, 36,37,38, 40], followed by sedatives including benzodiazepines [12, 32, 38, 41, 42], analgesics including paracetamol and NSAIDs [12, 27, 32, 38] and antimicrobials including pencillins [38, 42, 43], proton pump inhibitors [12, 32, 38] and potassium salts [41, 42]. Other less frequently reported medicine classes included calcium channel blockers [43], statins [32] and iron [32].

Qualitative studies

A total of 11 qualitative studies explored potential factors influencing the medicine use in cirrhotic patients [31, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of the qualitative studies, of which three were conducted in Iran [44,45,46] and the USA [31, 47, 48], two in Denmark [49, 50] and UK [51, 52] followed by one in Netherlands [53]. All the included studies were published between 2013 and 2015 and represented the view of 601 participants, of which 472 were patients with liver cirrhosis and 129 were healthcare professionals including specialist doctors and hepatology nurses. Thematic synthesis of the qualitative data identified three key themes related to medicine use in liver cirrhosis: (1) patient-related factors, (2) healthcare-related factors and (3) stigma (Table 3).

Patient-related factors

The patient-related factors included lack of knowledge, financial pressure, lack of motivation, patients’ beliefs and treatment issues.

Patients reported lack of knowledge about the nature of the disease, causes and complications [47, 49, 51]. Some patients held their doctors responsible for their poor knowledge about the disease [45, 52]. Patients indicated the need for more information about their medications and their possible side effects [46, 53]. Furthermore, some patients also reported lack of awareness about the risk factors associated with liver cirrhosis such as alcohol and drug abuse. However, some of these patients admitted that although they were aware of the risk factors, they still maintained an unhealthy lifestyle [47].

Lack of patients’ motivation towards their disease management including treatment was reported in two studies [44, 48]. The chronic nature of the disease and associated hospitalisation could have contributed to patients’ despair and hopelessness with regard to the outlook of their illness. Furthermore, patients’ beliefs about liver cirrhosis might also had changed their perception about the disease and its cure. Some patients believed that the disease is from (a will from) God [45] and the treatment will not help them as the only cure comes from God particularly during the advanced stages of the disease [45, 46]. However, for some, their faith and belief in God was a source of support that encouraged them to deal with the disease and adhere to their treatment [46].

Healthcare-related factors

The healthcare-related factors identified in the studies included barriers to accessing healthcare, communication between patients and healthcare providers (HCPs) and challenges faced by HCPs.

Lack of accessibility to healthcare was reported in four studies [31, 45, 47, 52]. From HCP perspectives, barriers to healthcare access involved factors related to patients, such as low motivation for treatment and low adherence. Financial constraints by patients were also one of the barriers reported by HCPs [31]. Patients discussed the high cost of medical services and problems with insurance companies with their HCPs [47]. Furthermore, fears of experiencing side effects, lack of awareness about the availability of support services [31] together with the long gaps between their appointments were some of the other barriers to healthcare access [31, 47, 52].

Importance of effective communication between patients and HCPs was highlighted in four studies [31, 46, 49, 52]. It was reported to have a positive impact on treatment as it improves patient’s adherence and their understanding of the condition and helps to forge a relationship based on trust between patients and HCPs [31, 46]. Some patients, however, reported lack of effective communication with HCPs due to a shorter consultation time and the use of medical jargons by HCPs [52]. Furthermore, poor communication and collaboration between HCPs and patients had resulted in discontinuity of patient care in some instances [49].

Challenges faced by HCPs were reported in three studies [31, 50, 52]. Unclear responsibilities were one of the challenges reported by HCPs in particular by primary care physicians (PCPs). PCPs, in general, reported their awareness about their roles in managing cirrhotic patients that included patient monitoring (symptoms and lab tests) and education [31]. However, some of them were reluctant to take decisions on the management or to contradict the specialists’ opinions [31, 52]. Reliance on specialist recommendation was common among PCPs [52]. Other challenges reported in the studies included the need for further training by hepatology nurses particularly on ADR recognition and management of oral health of patients with liver cirrhosis [50].

Stigma related to cirrhosis

The concept of stigma included negative attitudes (misconception and discrimination) and negative consequences.

Misconceptions about the disease were reported in four studies [44, 47, 48, 52]. Some patients linked the condition to substance abuse [44, 47] while others perceived the disease to be contagious [44, 48]. These misconceptions were commonly reported to have developed from within the social community [47, 48, 52]. Cirrhosis was perceived to be a self-caused condition due to the adoption of an unhealthy lifestyle [47, 48]. Furthermore, patients with cirrhosis also reported discriminations from both HCPs and general public. Some patients reported to have a limited social circle as some members of the public avoided interacting with them due to the risk of getting infectious [44, 48]. Some patients also preferred to deny the treatment and medical appointments offered by HCPs to avoid the risk of receiving negative judgement and discrimination from HCPs and close community [47].

The negative impact and consequences of the disease were reported in four studies [44, 47, 48, 52]. These included the psychological effects of the disease on patients including depression, low self-esteem and reduced quality of life [44, 48].

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review that brings together evidence from both quantitative and qualitative studies to gain an insight into MRPs in patients with liver cirrhosis. The findings of this review suggest that management of liver cirrhosis should not only be limited to the provision of safe and effective drug therapy but should also expand to improving the understanding of patients about the disease.

MRPs with a mean prevalence of 14–23.4% were reported to constitute a significant health problem in patients with cirrhosis. The mean prevalence reported in this review was higher compared with 8.3% reported in a previous review that involved 15 studies [54]. The higher prevalence of MRPs reported in the current review could be attributed to the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic changes associated with liver cirrhosis that consequently increases the incidence of MRPs [55] compared with other chronic conditions. Drug-drug interactions and inappropriate dosing were identified as the two major causes of MRPs in the review. Other less frequently reported causes included contraindicated drugs, unsuitable selection and erratic discontinuation of medicines. Similar findings have also been reported in a previous review involving hospitalised patients, which reported that around 17% of all documented MRPs were due to drug-drug interactions [56]. The use of lowest effective dose and dose adjustment according to renal and liver function are among some of the strategies that can prevent the incidence of dose-dependent MRPs [56].

Polypharmacy followed by associated comorbidities, severity of liver cirrhosis and length of hospital stay were among the most commonly reported risk factors for MRPS in this review. These findings are consistent with the findings of a cross-sectional study, which concluded that the number of prescribed drugs is a predictor of MRPs [57]. Polypharmacy is a known risk factor for both ADRs and MEs in many chronic diseases such as liver cirrhosis as they are often associated with comorbidities [58]. A study involving 827 patients conducted in hospital settings suggested that the number MRPs reported for each patient is linearly associated with the number of medications used at hospital admission [59]. The study further reported that a one unit increase in the number of medicines prescribed was associated with an increase in the number of MRPs by 8.6%.

Diuretics and sedatives were among the major medicine classes that were suspected to be associated with MRPs in patients with liver cirrhosis. A previous study that investigated the prescribing patterns and drug use in patients with liver cirrhosis highlighted that diuretics are one of the frequently prescribed medications in managing the complications of liver cirrhosis such as ascites [60]. The study also reported a significant association between diuretics chiefly furosemide and ADRs reported in the study population suggesting the need of careful monitoring of these drugs. Similarly, a review of 21 studies also implicated diuretics along with anti-inflammatory drugs in MRP-related hospital admissions [61]. Analgesics including paracetamol and NSAIDs were the other major medicine classes associated with MRPs. Paracetamol is generally considered to be safe in patients with liver cirrhosis but at a reduced dosage of 3 g/day [62]. In contrast, NSAIDs should be avoided in cirrhotic patients particularly during advanced stages due to the established risk of renal impairment and gastrointestinal bleeding [62, 63]. Furthermore, NSAIDs are metabolised by CYP enzymes that have reduced activity in cirrhosis and consequently raises NSAID plasma levels and increases the risk of adverse events [62].

Patients widely reported poor knowledge and understanding about the disease and its risk factors, associated complications and treatment. This lack of awareness has also been reported previously in an American study which suggested that patients with liver disease have limited knowledge about the safety of acetaminophen for pain management that can put them at risk of undermedication or overdose [64]. Another American study that involved liver transplant patients suggested that patients with a better understanding of their treatment and medication regimen were more likely to adhere to their treatment and can avoid the risk of hospitalisation [65]. Healthcare professional-led educational interventions including booklets, leaflets and videos have been associated with significant (< 0.001) improvement in patients’ knowledge and adherence to treatment in liver cirrhosis [30].

The review identified some of the challenges faced by healthcare professionals in managing cirrhotic patients that could negatively impact the control of the disease. Primary care physicians commonly raised uncertainty about roles and responsibilities as some of them believed that management of cirrhosis was a specialists’ responsibility [31]. Primary care physicians reported the need for further training to gain skills and confidence to enable them to manage cirrhotic patients particularly during advanced stages. An Italian study suggested that provision of training programs to primary care physicians allowed them to make early referrals to specialists that consequently improved the outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [66, 67]. The increased prevalence of cirrhosis necessitates the involvement of primary care physicians in managing liver cirrhosis. Efforts should be directed towards the provision of training and support with the aim of improving physicians’ knowledge and expertise about the optimal management of the disease.

This review has some limitations. The review did not include studies published in languages other than English that could have led to exclusion of valuable and relevant data. The review explored medicine use from patients’ and healthcare professionals’ perspectives only. The inclusion of family and caregivers in the review would have provided a more broad and extensive insight on the medicine use. Owing to the heterogeneity in the included studies, meta-analysis could not be conducted.

Conclusion

The findings of this review support the need of provision of safe and effective drug therapy together with patient-centred education to improve the medicine use in patients with liver cirrhosis. Furthermore, emotional and social support should also be provided to patients to improve their psychological well-being and outlook about the disease.

References

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R et al (2012) Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380:2197–2123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4

Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, Volk ML (2015) The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol 49:690–696. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208

Mokdad AA, Lopez AD, Shahraz S, Lozano R, Mokdad AH, Stanaway J, Murray CJL, Naghavi M (2014) Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med 12:145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y

Garcia-Tsao G (2016) Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis 34:382–386. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444551

Gines P, Quintero E, Arroyo V et al (1987) Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology 7:122–128

Groszmann RJ, Wongcharatrawee S (2004) The hepatic venous pressure gradient: anything worth doing should be done right. Hepatology 39:280–282

Tapper EB, Halbert B, Mellinger J (2016) Rates of and reasons for hospital readmissions in patients with cirrhosis: a multistate population-based cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 14:1181–88.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.04.009

Gonzalez M, Goracci L, Cruciani G, Poggesi I (2014) Some considerations on the predictions of pharmacokinetic alterations in subjects with liver disease. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 10:1397–1408. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425255.2014.952628

Verbeeck RK (2008) Pharmacokinetics and dosage adjustment in patients with hepatic dysfunction. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 64:1147–1161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0553-z

Domenicali M, Baldassarre M, Giannone FA, Naldi M, Mastroroberto M, Biselli M, Laggetta M, Patrono D, Bertucci C, Bernardi M, Caraceni P (2014) Posttranscriptional changes of serum albumin: clinical and prognostic significance in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 60:1851–1860

Lewis JH, Stine JG (2013) Prescribing medications in patients with cirrhosis—a practical guide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 37:1132–1156

Franz CC, Hildbrand C, Born C, Egger S, Rätz Bravo AE, Krähenbühl S (2013) Dose adjustment in patients with liver cirrhosis: impact on adverse drug reactions and hospitalizations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69:1565–1573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1502-z

Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ, Ramsey R, Lamsam GD (1990) Drug-related problems: their structure and function. DICP 24:1093–1097

Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe. PCNE classification of drug related problems. Pharmaceutical care network Europe foundation (2016). http://www.pcne.org/upload/files/145_PCNE_classification_V7-0.pdf (accessed 19 Nov 2018)

Volk ML, Fisher N, Fontana RJ (2013) Patient knowledge about disease self-management in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 108:302–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2012.214

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151:264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N et al (1995) Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. JAMA 274:29–34

Barber N, Parson J, Clifford S, Darracott R, Home R (2004) Patients’ problems with new medication for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 13(3):172–175

WHO (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence fo action. World Health Organisation, Geneva

Ferner RE, Aronson JK (2006) Clarification of terminology in medication errors: definitions and classification. Drug Saf 29:1011–1022

Hepler CD, Strand LM (1990) Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Pharm Educ 53:S7–S15

Chan DC, Chen JH, Wen CJ, Chiu LS, & Wu SC (2012). Effectiveness of the medication safety review clinics for older adults prescribed multiple medications. J Formosan Med Assoc.

Kaufmann CP, Stämpfli D, Hersberger KE, Lampert ML (2015 Mar 1) Determination of risk factors for drug-related problems: a multidisciplinary triangulation process. BMJ Open 5(3):e006376

World Health Organization (1985) The rational use of drugs. Reports of the conference of experts. Geneva: WHO. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s17054e/s17054e.pdf (accessed 21 Nov 2018)

Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Franz CC, Egger S, Born C, Rätz Bravo AE, Krähenbühl S (2012) Potential drug-drug interactions and adverse drug reactions in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 68:179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-011-1105-5

Suresh A, Majun A, Kumar A et al (2016) A prospective observational study on evaluation of patients counselling by clinical pharmacist in improving knowledge, attitude, and practice in patients with cirrhosis at a tertiary care hospital. JJPPR 8:116–127

Sumbul S, Shumaila S (2015) Evaluation of occurrence of medication errors in liver disease patients. BJMMR 10:1–8

Beg S, Curtis S, Shariff M (2016) Patient education and its effect on self-management in cirrhosis: a pilot study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28:582–587. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000579

Burnham B, Wallington S, Jillson IA, Trandafili H, Shetty K, Wang J, Loffredo CA (2014) Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of patients with chronic liver disease. Am J Health Behav 38:737–744

Derijks LJ, Ruiz EM, Van de Poll MC et al (2013) Drug choice and dose adjustments in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Top Pharmacol 17:41–46

Lorensia A, Hubeis A, Bagijo H, et al (2008) Adverse drug reaction (ADR) study in hospitalised hepatic cirrhosis patients Dr. Ramelan Navy Hospital. Proceeding of international conference on pharmacy and advanced pharmaceutical sciences, Indonesia

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2014) CASP Checklists Oxford. CASP http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists (accessed 10 Oct 2018)

National heart, Lung, and blood institute (2014) Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross sectional studies. NIH https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (accessed 10 Oct 2018)

Hayward KL, Valery PC, Cottrell WN (2016) Prevalence of medication discrepancies in patients with cirrhosis: a pilot study. BMC Gastroenterol 16:114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-016-0530-4

Polis S, Zang L, Mainali B (2016) Factors associated with medication adherence in patients living with cirrhosis. J Clin Nurs 25:204–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13083

Sistanizad M, Peterson GM (2013) Use of contraindicated drugs in patients with chronic liver disease: a therapeutic dilemma. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 51:1–4. https://doi.org/10.5414/CP201705

Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Heuman DM, Thacker LR, Sterling RK, Stravitz TR, Luketic V, Fuchs M, White MB, Bell DE, Gilles HC, Morton K, Noble N, Puri P, Sanyal AJ (2011) The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol 106:1646–1653. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.157

Kuo SZ, Haftek M, Lai JC (2017) Factors associated with medication non-adherence in patients with end-stage liver disease. Dig Dis Sci 62:543–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-016-4391-z

Naranjo CA, Busto U, Mardones R (1978) Adverse drug reactions in liver cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 13:429–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00566321

Naranjo CA, Busto U, Janecek E (1983) An intensive drug monitoring study suggesting possible clinical irrelevance of impaired drug disposition in liver disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 15:451–458

Lorensia A, Hubeis A, Widyati, et al (2009) Drug interaction study in hospitalised hepatic cirrhosis patient in Dr. Ramelan Navy Hospital. Proceeding of international conference on pharmacy and advanced pharmaceutical sciences, Indonesia

Shabanloei R, Ebrahimi H, Ahmadi F, Mohammadi E, Dolatkhah R (2016) Stigma in cirrhotic patients a qualitative study. Gastroenterol Nurs 39:216–226

Shabanloei R, Ebrahimi H, Ahmadi F, Mohammadi E, Dolatkhah R (2017) Despair of treatment: a qualitative study of cirrhotic patients’ perception of treatment. Gastroenterol Nurs 40:26–37

Abdi F, Daryani NE, Khorvash F, Yousefi Z (2015) Experiences of individuals with liver cirrhosis: a qualitative study. Gastroenterol Nurs 38:252–257

Beste LA, Harp BK, Blais RK, Evans GA, Zickmund SL (2015) Primary care providers report challenges to cirrhosis management and specialty care coordination. Dig Dis Sci 60:2628–2635

Vaughn-Sandler V, Sherman C, Aronsohn A, Volk ML (2014) Consequences of perceived stigma among patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 59:681–686

Fagerström C, Frisman GH (2017) Living with liver cirrhosis: a vulnerable life. Gastroenterol Nurs 40:38–46

Groenkjaer LL (2015) Oral care in hepatology nursing: nurses’ knowledge and education. Gastroenterol Nurs 38:22–30

Goldworthy MA, Fateen W, Thygesen H et al (2017) Patient understanding of liver cirrhosis and improvement using multimedia education. Frontline Gastroenterol 8:214–219

Kimbell B, Boyd K, Kendall M, Iredale J, Murray SA (2015) Managing uncertainty in advanced liver disease: a qualitative, multi-perspective, serial interview study. BMJ Open 5:e009241

Borgsteede SD, Weersink R, Van der Wal M et al (2017) Informational needs about medication of patients with liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Pharm 39:250

Nivya K, Sri Sai Kiran V, Ragoo N, Jayaprakash B, Sonal Sekhar M (2013) Systemic review on drug related hospital admissions—a PubMed based search. Saudi Pharm J 23(1):1–8

Westphal JF, Brogard JM (1997) Drug administration in chronic liver disease. Drug Saf 17:47–73

Krahenbuhl-Melcher A, Schlienger R, Lampert M et al (2007) Drug-related problems in hospitals. Drug Saf 30:379–407

Koh Y, Kutty FB, Li SC (2005) Drug-related problems in hospitalized patients on polypharmacy: the influence of age and gender. Ther Clin Risk Manag 1:39–48

Sato I, Akazawa M (2013) Polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions in Japanese elderly taking antihypertensives: a retrospective database study. Drug, Healthc Patient Saf 5:143

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A (2007) Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol 63:187–195

Lucena IM, Andrade RJ, Tognoni G et al (2002) Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 58:435–440

Al Hamid A, Ghaleb M, Aljadhey H et al (2014) A systematic review of qualitative research on the contributory factors leading to medicine-related problems from the perspectives of adult patients with cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open 4:e005992

Imani F, Motavaf M, Safari S, Alavian SM (2014) The therapeutic use of analgesics in patients with liver cirrhosis: a literature review and evidence-based recommendations. Hepat Mon 14:e23539

Sahasrabuddhe VV, Gunja MZ, Graubard BI, Trabert B, Schwartz LM, Park Y, Hollenbeck AR, Freedman ND, McGlynn KA (2012) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, chronic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 104:1808–1814

Saab S, Konyn PG, Viramontes MR, Jimenez MA, Grotts JF, Hamidzadah W, Dang VP, Esmailzadeh NL, Choi G, Durazo FA, el-Kabany MM, Han SB, Tong MJ (2016) Limited knowledge of acetaminophen in patients with liver disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol 4:281–287. https://doi.org/10.14218/JCTH.2016.00049

Serper M, Patzer RE, Reese PP, Przytula K, Koval R, Ladner DP, Levitsky J, Abecassis MM, Wolf MS (2015) Medication misuse, nonadherence, and clinical outcomes among liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 21:22–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.24023

Del Poggio P, Olmi S, Ciccarese F et al (2015) A training program for primary care physicians improves the effectiveness of ultrasound surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27:1103–1108

Aronson JK, Ferner RE (2005) Clarification of terminology in drug safety. Drug Saf 28:851–870

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author AH developed the research question. Author AA conducted the searches and extracted the data. Both AH and AA analysed the data and did the quality assessment. Author EC contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Search strategies used in the major electronic databases

Embase:

-

1)

Medicine use.mp.

-

2)

Medicine related problems.mp. Or drug related problems. Or adverse drug event. Or adverse drug reaction. Or medication error.

-

3)

1 or 2

-

4)

Exp liver cirrhosis / or Hepatic cirrhosis/

-

5)

chronic liver diseases *.mp.

-

6)

4 or 5

-

7)

Exp Knowledge / or beliefs *.mp.

-

8)

attitude *.mp.

-

9)

3 and 6 and 7 and 8.

-

10)

limit 9 to (English language and (adult <18 to 100 years)

Medline Ovid:

-

1)

Medicine use.mp.

-

2)

Medicine related problems / or drug related problems.mp. Or adverse drug event. Or adverse drug reaction. Or medication error.

-

3)

liver cirrhosis.mp. or exp Hepatic cirrhosis /

-

4)

1 or 2 or 3

-

5)

1 or 3

-

6)

Exp Knowledge / or beliefs *.mp.

-

7)

attitude *.mp.

-

8)

5 and 6 and 7

-

9)

4 and 6 and 7

-

10)

limit 8 to (English language and (“all adult (18 plus years)”

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheema, E., Al-Aryan, A. & Al-Hamid, A. Medicine use and medicine-related problems in patients with liver cirrhosis: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75, 1047–1058 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02688-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02688-z