Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

This study synthesized the effects of supervised and unsupervised pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) programs on outcomes relevant to women’s urinary incontinence (UI).

Methods

Five databases were searched from inception to December 2021, and the search was updated until June 28, 2022. Randomized and non-randomized control trials (RCTs and NRCTs) comparing supervised and unsupervised PFMT in women with UI and reported urinary symptoms, quality of life (QoL), pelvic floor muscles (PFM) function/ strength, the severity of UI, and patient satisfaction outcomes were included. Risk of bias assessment of eligible studies was performed by two authors through Cochrane risk of bias assessment tools. The meta-analysis was conducted using a random effects model with the mean difference or standardized mean difference.

Results

Six RCTs and one NRCT study were included. All RCTs were assessed as "high risk of bias", and the NRCT study was rated as "serious risk of bias" for almost all domains. The results showed that supervised PFMT is better than unsupervised for QoL and PFM function of women with UI. There was no difference between supervised and unsupervised PFMT for urinary symptoms and improvement of the severity of UI. Results of patient satisfaction were inconclusive due to the sparse literature. However, supervised and unsupervised PFMT with thorough education and regular reassessment showed better results than those for unsupervised PFMT without educating patients about correct PFM contractions.

Conclusions

Supervised and unsupervised PFMT programs can both be effective in treating women's UI if training sessions and regular reassessments are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined as a "complaint of involuntary loss of urine” that is associated with extreme physical, psychological, and social consequences, resulting in impaired quality of life (QoL) [1, 2]. UI is a common condition that affects millions of people, but it is more prevalent among women [3]. Several types of UI exist, and the most common subtypes are stress, urgency, and mixed UI [4]. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is the most prevalent type of UI and refers to involuntary urine loss upon effort, exertion, sneezing, and coughing. Urgency UI (UUI) is defined as the complaint of involuntary leakage associated with urgency, and if both stress and urgency are present at the same time, it is called mixed UI (MUI) [5].

Physiotherapy is a well-known conservative treatment for UI. Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is considered the first line of treatment of UI based on current literature [6] This is an exercise that increases pelvic floor muscle (PFM) power, strength, and endurance. Studies have reported a 56–75% success rate for PFMT [7, 8]. Hypertrophy of these muscles followed by increasing force of contraction can provide adequate support for the urethra and anterior vaginal wall [9]. Being cost-effective and safe makes PFMT the only treatment without any restrictions [10].

Supervised PFMT programs are currently provided in physiotherapy clinics, where women attend training sessions at specified intervals and participate in either individual or group coaching sessions. Although supervised PFMT programs are effective [11], women enrolled in supervised programs may face challenges. As women need to travel to and from clinical locations, travel can become a barrier to care over time, especially for those living in rural areas. Long-distance and frequent transportation can increase financial, physical, and/or psychological stress. To overcome these challenges, unsupervised PFMT might be recommended. Evidence from a qualitative study showed that participants in unsupervised programs felt confident in self-training and felt it provided them with the ability to take charge of their symptoms [12]. Evidence of the effectiveness of interventions is necessary to prescribe these treatments. Therefore, this study aimed to review published randomized and non-randomized control trials (RCTs and NRCTs) that assessed the effects of unsupervised PFMT programs in comparison with supervised PFMT programs for managing UI symptoms, quality of life (QoL), PFMs function/ strength, the severity of UI, and patient's satisfaction outcomes in female adults.

Method

This systematic review was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of supervised and unsupervised PFMT on women with UI. The study was prepared according to the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) methodology [13], and the protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021292521).

Search strategy

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (via PubMed), The Cochrane Library (CENTRAL), Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). All databases were searched from inception to December 2021, and the search was updated until June 28, 2022. Finally, the reference list of all articles selected for critical appraisal and grey literature were searched for additional studies. The full search strategy of MEDLINE, Scopus, and WoS is provided in Appendix I.

Study selection

Studies were included if they met all the following criteria: 1) studies with RCT or NRCT designs, 2) studies evaluating the efficacy of unsupervised PFMT programs in comparison with supervised PFMT programs for managing any type of UI (including SUI, UUI, and/ or MUI), 3) studies with adult females (≥ 18 years of age) as participants, and 4) studies that assessed the effects of supervised and unsupervised PFMT on UI symptoms and/or QoL and/or PFMs function/ strength and/or severity of UI and/ or participants’ satisfaction with the treatment. Studies that included post-partum or pregnant women with UI were excluded from this review.

One reviewer conducted the database searches and removed duplicates using EndNote X9.1 software. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers to evaluate the studies according to the inclusion criteria. The full texts of potentially entitled studies were assessed according to the inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Risk of bias assessment

To assess the potential bias that may affect the cumulative evidence, the following tools were used: the Cochrane tool for assessing the risk of bias in RCTs (RoB-2) [14], and the tool for assessing the risk of bias in NRCT studies of intervention (ROBINS-1) [15]. Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were discussed with a third reviewer.

The RoB-2 tool evaluates five domains in RCTs: randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported results [14]. ROBINS-1 evaluates seven domains of bias: confounding bias, selection bias, measurement bias, intervention bias, missing data bias, outcome bias, and selective reporting bias [15].

RoB-2 was rated as high, low, and some concerns, and ROBINS-1 was rated as low, moderate, serious, critical RoB, and “no information” when insufficient data is available to permit a judgment according to the Cochrane handbook and the technical guidance document of the RoB-2 tool [16].

Data extraction

Two reviewers extracted the data independently from the eligible studies. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. The following information was extracted from the included studies: authors, publication year, sample size, details of the interventions (e.g., type, timing, and duration of treatment sessions), outcomes and measurements used, and study results.

Authors of papers were contacted to request missing or additional data. In addition, when unpublished works were retrieved in our search, an email was sent to the corresponding author(s) to determine whether the work has been subsequently published. If no response had been received from the corresponding author(s) after three emails, the study was excluded.

Analysis

Mean difference and standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval were synthesized by a random-effect model. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). The I2 statistic was applied to evaluate the heterogeneity of included studies.

Results

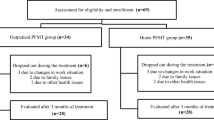

The process of study selection is summarized in Fig. 1. A total of 2735 studies were identified during the electronic and hand-search processes. After title/abstract screening, 75 studies were retrieved as full-text articles. The full-text versions of 69 studies were assessed, and six RCTs [17,18,19,20,21,22] and one NRCT [23] studies were included in this review

Risk of bias assessment

Six studies [17,18,19,20,21,22] were assessed according to the RoB-2 tool [14] and all of them were assessed as “high risk of bias” (Fig. 2) and summarised in the risk of bias graph (Appendix 2). The risk of bias domain that mostly received the rating “high” was “Risk of bias in the measurement of the outcome”, which was related to the awareness of outcome assessors and participants about the assignment to the intervention groups. Knowledge of assigned intervention could influence participant-reported outcomes (such as QoL) which were rated as a risk factor for biased results. Also, assessor awareness of intervention assignment may result in assessor judgment.

The remaining study [23] was assessed according to the ROBINS-1 tool [15], which was rated as a “serious risk of bias” (Fig. 3). The risk of bias assessment resulted in many “No information” due to the non-availability of the study protocol and inadequate reporting about confounding factors, selection of participants and deviations from intended interventions, and “serious risk of bias” ratings in almost all domains except in the domain assessing the risk of bias in the selection of the reported result, which was rated as “low risk of bias”.

Participants

All seven studies [17,18,19,20,21,22,23] included women with SUI,and in one study [22] women with UUI and MUI were also included. Other types of UI were not assessed in the studies. The total number of participants was 312 women, and the mean ages ranged between 45.61 [22] to 57.7 [17]. The sample sizes ranged from 10 [19] to 35 [17].

Components of supervised and unsupervised protocols

Treatment duration

All studies included a group with supervised sessions under the supervision of a physiotherapist [17,18,19,20,21, 23]. With regard to the duration of treatment, it varied from 5 weeks to 1 year, with a weekly frequency of 1 to 2 times and sessions of 30 [21] to 50 [20] minutes.

PFMT parameters

All of the PFMT parameters were the same in both supervised and unsupervised groups of each study, except for one study that received interferential and biofeedback training in each supervised session [23]. In one of the included studies, weighted vaginal balls were used in both groups [23]. Only in one study, joint warm-up exercises at the beginning and stretching exercises at the end of each session were performed [18].

Three studies reported that participants in both supervised and unsupervised groups were educated about the correct contraction of PFMs through biofeedback [23], digital palpation [21], or one supervised session at the beginning [18, 22]. Others only received exercise diaries [17, 19, 20]. Almost all studies received PFME in horizontal positions, and progressed the program by changing the position to vertical and increasing the hold time of contractions [17, 18, 20, 21, 23]. Some of the included studies applied both low and high-intensity contractions in their program [18, 19, 21, 23], but others just asked participants to do the maximum contraction [19, 20]. Three included studies asked participants to do PFMs contraction with coughing (Knack maneuver) [18, 21, 23].

Reinforcement techniques

Three included studies reinforced the treatment with a monthly reassessment of PFMs through vaginal palpation performed by the physiotherapist in both supervised and unsupervised groups [17,18,19]. Two studies educated participants of both groups to do a self-digital assessment [21, 23].

Outcomes

Symptom diagnosis/ screening outcomes are presented in Table 1.

QoL

Six studies measured QoL through different outcome measures including the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ–SF; higher scores are worse) [20, 21], QoL index (higher scores are worse) [18, 19], Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ7; higher scores are worse) [22] and Incontinence–Quality of Life (I–QoL; higher scores are better — the direction of effect was inverted in the meta-analysis to allow the combination with other QoL outcome results) [17]. All but one study [18] reported significant improvement in QoL scores in both groups. Five studies were included in the meta-analysis [17, 19,20,21,22]; however, one study [18] reported the findings as median and thus was not included in the meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis revealed a moderate effect in favour of the supervised group (SMD = −0.64; 95% CI: −1.25 to −0.02) with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 75.4%) (Fig. 4).

Urinary symptoms

A total of six studies [17,18,19,20,21, 23] assessed the effects of supervised and unsupervised PFMT on urinary symptoms. Both supervised and unsupervised PFMT groups displayed significant improvements in urinary symptom outcomes. To evaluate treatment results based on the amount of leakages, five studies used the pad test with different duration [17,18,19,20, 23]. Three studies could be included in the meta-analysis [17, 20, 23]. The overall SMD was −0.34 (95% CI, −3.158 to 2.46) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 44.5%), which revealed no difference between supervised and unsupervised groups for urinary symptom improvement (Fig. 5).

Among six studies that compared the effects of supervised and unsupervised PFMT on the urinary symptom, three studies were not included in the meta-analysis since the required data for meta-analysis had not been included and their measurement methods were not identical to other studies. In the study of Nagib et al. [21], results of ICIQ-SF showed improvement of urinary symptoms in both supervised and unsupervised groups after the intervention, with statistically significant better results in the supervised group. Zanetti et al. [18] showed a significant decrease in urine leakage based on use of a urine diary in both supervised and unsupervised groups; however, the supervised group showed better results. The results of the pad test in the study of Konstantinidou et al. [19] showed improvement of the urinary symptoms specifically in the supervised group, however, the micturition diary showed statistically significant improvement in incontinence episodes per week and 24-hour frequency in both supervised and unsupervised groups.

PFMs function/ strength

Five studies assessed the effects of supervised and unsupervised PFMT on PFMs function/ strength. Of these, four studies used the Oxford scale [17, 19,20,21] and, one of them also used PERFECT [21]. The remaining study used electromyography [23]. For the Oxford scale, a meta-analysis was conducted on three studies providing sufficient statistical information. The pooled data showed a significant difference between the two groups in favour of supervised PFMT (SMD = 1.11; 95% CI: 0.28 to 1.93) with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 74%) (Fig. 6). Of two studies that were not included in the meta-analysis, one study reported no differences between supervised and unsupervised groups [23], and the results of the other study showed significantly better improvement in the supervised group [17].

Improvement in the severity of UI

Five studies reported the improvement/cure of the severity of UI [17, 19, 20, 22, 23] following PFMT programs. Three studies reported objective cure/improvement [17, 20, 23] of which one also reported subjective cure/improvement [23] and two remaining studies only assessed subjective improvement [19, 22]. Fitz et al. [17] showed 61.% cure rate in the supervised group compared with 28.6% in the unsupervised group. Felicissimo et al. [20] showed objective cure/improvement in both groups based on negative pad test in 36.6% of patients in the supervised group and 34.5% in the unsupervised group post-intervention. Also, subjective cure which was measured by simple questions about the patient's feelings about their problem after the treatment showed similar improvement in both groups [20]. Konstantinidou et al. [19] showed significantly more improvement in symptoms based on patient global impression of improvement (PGI-I) in the supervised group compared with the unsupervised. In the study of Parkinnen et al. [23], the cure rate was 37.5% and 11.8% in supervised and unsupervised groups respectively. Also, respectively, 31.3% and 47.1% of patients in supervised and unsupervised groups reported improvement in symptoms [23]. In the study of Mishra et al. [22]; significantly more improvement was seen after 6 months of treatment in a supervised group.

Patient satisfaction

Three studies contributed data for patient satisfaction with inconclusive results [17, 18, 20]. One study showed better results in the supervised group due to not requiring further treatment compared to the unsupervised group, based on subjective evaluation [18], however, the other two studies showed no differences between groups based on patient's willingness to change their treatment [17, 20].

Discussion

This study was a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of the supervised versus unsupervised PFMT for the treatment of women with UI. The findings of the present systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the QoL and PFM function improved significantly in the supervised group compared to the unsupervised. There was not a significant difference in the severity of UI, and the results of studies that reported patient satisfaction were inconclusive. This systematic review and meta-analysis differ from the existing Cochrane review of PFMT for UI which is limited to the comparison of PFMT to no treatment, placebo/sham, or inactive treatment [6]. Previous reviews have not compared supervised and unsupervised PFMT programs for the treatment of women with UI. This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the outcomes of UI symptoms, QoL, PFM function/ strength, and severity between supervised and unsupervised PFMT programs.

Based on the results of the present study, supervised PFMT was associated with a greater improvement in QoL when compared to the unsupervised PFMT group. This finding might be related to the significant improvement of PFM function/ strength in the supervised group. Increasing PFM strength and ability to maintain contraction can improve PFM functionality and QoL in women with UI [21, 24].

The current meta-analysis revealed no significant difference between supervised and unsupervised groups for urinary symptom improvement. However, not all the included studies produced nonsignificant results. Unsupervised PFMT programs are defined as self-administered training programs with or without education sessions [20], although wide variations in implementing these programs are available. A disadvantage of unsupervised PFMT programs that probably reduces their effectiveness compared to supervised programs is the inability to perform the exercises correctly [25]. It is well known that the primary cause of treatment failure is the inaccurate performance of the exercises and lack of knowledge about the pelvic floor [26]. Interestingly, studies that reported no difference in the urinary symptoms between groups [17, 20, 23] had provided explanations about the anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract for the unsupervised PFMT group. Also, in these studies, inappropriate contractions were corrected and treatment adherence was motivated.

Despite all studies showing improved PFM function/strength for both groups, the results of the meta-analysis revealed a greater impact of supervised PFMT in comparison with unsupervised programs, with a strong effect size. In most of the studies that assessed the effects of supervised and unsupervised PFMT on PFMs function/ strength, therapists who supervised the activities in the supervised group prescribed the combination of the supervised PFMT program with the program recommended for the unsupervised group [17, 19, 21]. It is possible that this strategy contributed to the positive results observed in the supervised PFMT group but not in the unsupervised PFMT group.

The results of the meta-analysis demonstrated no differences in the improvement of SUI severity among the groups; most studies had applied a pad test to evaluate the severity of UI and reported no differences between supervised and unsupervised PFMT groups [17, 20, 23]. However, not all studies were included in the meta-analysis, and the chance of objective cure of UI was four times more in the supervised PFMT group [17]. In addition, another study reported significantly better subjective results for the supervised PFMT group [22]. In most studies that found reduced UI severity, the function/strength of the PFMs had improved with intervention in both groups [17, 20, 23]. UI severity is correlated with PFM strength [27]. When the PFM contraction is effective, well-timed, fast, and strong, the leakage rate decreases during an increase in intra-abdominal pressure; this is facilitated by preventing urethral descent or increasing urethral pressure via either urethral clamping or mechanical compression in the pubis symphysis [9, 17, 28].

The effectiveness of supervised and unsupervised PFMT on the satisfaction of women with SUI was also assessed. Two studies [17, 20] observed no significant difference between supervised and unsupervised PFMT groups, and both groups were equally satisfied with the intervention. However, one study found lower satisfaction in the unsupervised group [18]. This inconsistency observed between the studies’ findings could be due to different teaching methods implemented. Providing information concerning the lower urinary tract anatomy and physiology, correcting inappropriate contractions, and motivating and encouraging individuals for the accurate performance of PFMT have key roles in satisfaction. These factors were considered for both intervention groups in the studies of Felicíssimo et al. and Fitz et al [17, 20]. Therefore, an online or in-person educational session at the beginning of the treatment is recommended. Also, using reinforcement techniques including regular reassessment of patients, self-assessment, and vaginal palpation, to ensure correct PFM contraction, is indicated.

Strengths and limitations

This study may be the first systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed the impact of supervised and unsupervised PFMT in women with UI. The findings of the study were based on a comprehensive search strategy through existing literature, and presented following the PRISMA guidelines. As UI is one of the main concerns of the aging process that makes the affected person isolated, and accessibility to outpatient centers is difficult for patients, specifically during the COVID-19 pandemic, the results of this study would be practical considering the presentation of the best way of performing unsupervised PFMT to improve the UI severity. Also, in this study, we used Cochrane RoB assessment tools, RoB 2.2 and ROBINS-1, which focus on different aspects of trials.

However, the review has some limitations. Most studies included women with SUI, so results may not be generalizable to other types of UI, and this should be noticed in future studies. Results concerning contraction types and duration of the treatments were highly heterogeneous and the RoB score of the included studies was high, particularly for the measurement of the outcome; therefore, the results of this review should be implicated with caution.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that both supervised and unsupervised PFMT has positive effects on QoL, PFM function, urinary symptoms, and the severity of UI. Although supervised PFMT showed better results in most of the included studies compared with unsupervised PFMT, the improvement of urinary symptoms and severity of UI was almost the same between the two groups.

Implication for research

With regard to the sparse amount of research, well-designed trials are required comparing supervised and unsupervised PFMT in women with UI. It is recommended that identical and valid outcome measures should be used to facilitate reviewing literature systematically and reach a more accurate conclusion. Also, presenting a detailed PFMT program including the number of sets and repetitions, body positions, duration of hold and rest, types of contractions, duration of each session, home exercises, and warm-up and cool-down exercises would produce a standardized home and outpatient PFMT program. Finally, long-term follow-up is recommended.

References

Tettamanti G, Altman D, Iliadou AN, Bellocco R, Pedersen NL. Depression, neuroticism, and urinary incontinence in premenopausal women: a nationwide twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16(5):977–84.

Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Psychosocial and societal burden of incontinence in the aged population: a review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277(4):285–90.

Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, Cornu JN, Daly JO, Cartwright R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17042.

Russo E, Caretto M, Giannini A, Bitzer J, Cano A, Ceausu I, et al. Management of urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women: An EMAS clinical guide. Maturitas. 2021;143:223–30.

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):4–20.

Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2018;10(10):Cd005654.

Freeman RM. The role of pelvic floor muscle training in urinary incontinence. BJOG. 2004;111(Suppl 1):37–40.

Castro RA, Arruda RM, Zanetti MR, Santos PD, Sartori MG, Girão MJ. Single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no active treatment in the management of stress urinary incontinence. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2008;63(4):465–72.

Bø K. Pelvic floor muscle training is effective in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, but how does it work? Int Urogynecol J. 2004;15(2):76–84.

Bø K, Talseth T, Holme I. Single blind, randomised controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no treatment in management of genuine stress incontinence in women. BMJ. 1999;318(7182):487–93.

Bø K, Frawley HC, Haylen BT, Abramov Y, Almeida FG, Berghmans B, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the conservative and nonpharmacological management of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(2):221–44.

Asklund I, Samuelsson E, Hamberg K, Umefjord G, Sjöström M. User experience of an app-based treatment for stress urinary incontinence: qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e11296-e.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Higgins JP, Savović J, Page MJ, Sterne JA. Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2). Bristol: University of Bristol; 2016.

Hinneburg I. ROBINS-1: a tool for asssessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2017;40(4):175–7.

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2019;10:ED000142..

Fitz F, Gimenez M, Ferreira L, Bortolini M, Castro R. Pelvic floor muscle training for female stress urinary incontinence: a randomized control trial comparing home and outpatient training. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:S45–S6.

Zanetti MR, Castro Rde A, Rotta AL, Santos PD, Sartori M, Girão MJ. Impact of supervised physiotherapeutic pelvic floor exercises for treating female stress urinary incontinence. Sao Paulo Med J. 2007;125(5):265–9.

Konstantinidou E, Apostolidis A, Kondelidis N, Tsimtsiou Z, Hatzichristou D, Ioannides E. Short-term efficacy of group pelvic floor training under intensive supervision versus unsupervised home training for female stress urinary incontinence: a randomized pilot study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26(4):486–91.

Felicíssimo MF, Carneiro MM, Saleme CS, Pinto RZ, Da Fonseca AMRM, Da Silva-Filho AL. Intensive supervised versus unsupervised pelvic floor muscle training for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized comparative trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(7):835–40.

Nagib ABL, Silva VR, Martinho NM, Marques A, Riccetto C, Botelho S. Can supervised pelvic floor muscle training through gametherapy relieve urinary incontinence symptoms in climacteric women? a feasibility study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2021;43(7):535–44.

Mishra DG, Vaishnav SB, Phatak AG. Comparison of effectiveness of home-based verses supervised pelvic floor muscle exercise in women with urinary incontinence. J Midlife Health. 2022;13(1):74–9.

Parkkinen A, Karjalainen E, Vartiainen M, Penttinen J. Physiotherapy for female stress urinary incontinence: Individual therapy at the outpatient clinic versus home-based pelvic floor training: a 5-year follow-up study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(7):643–8.

Al Belushi ZI, Al Kiyumi MH, Al-Mazrui AA, Jaju S, Alrawahi AH, Al Mahrezi AM. Effects of home-based pelvic floor muscle training on decreasing symptoms of stress urinary incontinence and improving the quality of life of urban adult Omani women: a randomized controlled single-blind study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(5):1557–66.

Radzimińska A, Strączyńska A, Weber-Rajek M, Styczyńska H, Strojek K, Piekorz Z. The impact of pelvic floor muscle training on the quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: a systematic literature review. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:957–65.

Alewijnse D, Mesters I, Metsemakers J, Adriaans J, Van Den Borne B. Predictors of intention to adhere to physiotherapy among women with urinary incontinence. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(2):173–86.

Bø K. Pelvic floor muscle strength and response to pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2003;22(7):654–8.

Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. A pelvic muscle precontraction can reduce cough-related urine loss in selected women with mild SUI. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(7):870–4.

Authors' contribution to the manuscript

Ghazal Kharaji: protocol development, writing manuscript, editing, interpreting the relevant literature, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Shabnam ShahAli: protocol development, writing manuscript, editing, interpreting the relevant literature, revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Ismail Ebrahimi-Takamjani: writing manuscript, editing.

Javad Sarrafzadeh: data collection, editing.

Fateme Sanaei: data collection, editing.

Sanaz Shanbehzadeh: data analysis, interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kharaji, G., ShahAli, S., Ebrahimi-Takamjani, I. et al. Supervised versus unsupervised pelvic floor muscle training in the treatment of women with urinary incontinence — a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 34, 1339–1349 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05489-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05489-2