Abstract

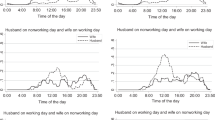

We examine how men and women in mixed-gender unions change the time they allocate to housework in response to labor market promotions and terminations. Operating much like raises, such events have the potential to alter intra-household power dynamics. Using Australian panel data, we estimate couple-specific fixed effects models and find that female promotion has the strongest association with housework time allocation adjustments. These adjustments are in part attributable to concurrent changes in paid work time, but gender power relations also appear to play a role. Further results indicate that households holding more liberal gender role attitudes are more likely to adjust their housework time allocations after female promotion events. Power dynamics cannot, however, explain all the results. Supporting the sociological theory that partners may “do gender,” we find that in households with more traditional gender role attitudes, his housework time falls while hers rises when he is terminated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Stancanelli and Stratton (2014) present evidence from the UK and France that cleaning, ironing, laundry, and doing dishes are in fact not very enjoyable tasks. More people enjoy cooking. The same has historically also been true in the USA (Ramey 2009). The results in Rapoport et al. (2011) support the claim that time spent outside paid work is not pure leisure, and Connelly and Kimmel (2015) further show that on average, routine housework tasks are not enjoyed any more than paid work.

An alternative interpretation of a negative relation between earnings and housework time is that partners’ relative wages reflect their comparative advantages, such that the partner with the highest market-based opportunity cost has a comparative advantage in performing paid as compared to unpaid labor.

One exception is Baxter and Hewitt (2013).

In sensitivity analysis where she drops those unpaid labor activities most likely to be utility-generating, Bredtmann (2014) also finds a negative relation between his paid labor time and her unpaid labor time.

Simple labor supply models assume individuals are free to choose how many hours to supply to the labor market. Here, we assume instead that individuals accepting a job or a promotion must simultaneously accept the hours the employer offers as part of that new position.

Importantly, when we include controls for paid work time, we do not interpret the estimated coefficients on those controls as causal. This is because despite our inclusion of fixed effects, these estimates will still be afflicted by endogeneity to the extent that individuals simultaneously change their allocation of time to different uses for the same unobserved third-party reason (see Jenkins and O’Leary (1995) for a more detailed discussion of the endogeneity problem). Nonetheless, to the extent that the unobserved third-party factors influencing time allocations to both activities are independent of the labor market events we observe, including controls for paid work enables us to interpret the coefficients on those events as picking up something other than mechanical housework time adjustments.

On a more basic level, however, the goal is presumably happiness. The role of factors such as personal beliefs and social pressure as inputs to the happiness produced by one’s household environment and choices has received relatively little attention in the economics literature.

Throughout the paper, we will use the term “household couple” to refer to the two adults—one male and one female—who together form the base of each household in our sample.

We exclude childcare for a variety of reasons: childcare is frequently multitasked (often with leisure), it is extremely time-consuming compared to other types of household labor, it is to some degree more efficiently performed by women (e.g., when feeding a nursing baby is involved), and it is virtually impossible to completely outsource. It also produces public goods of a very different, emotionally laden sort (i.e., happy, functional children) than other types of household labor. Empirical work by Kimmel and Connelly (2007) yields evidence that the explanatory factors associated with childcare are in fact quite different from those associated with housework.

The excess term in our model also accommodates such psycho-social motivations as “doing gender.”

Either technological improvements or psychological/social factors may result in households accommodating changes in their paid labor time through changes in the fraction of housework performed in a multitasking, as opposed to sole-tasking, context. In the present paper, we acknowledge this possibility, but we do not separately measure sole-tasked and multitasked household work (see Kalenkoski and Foster 2016 for further discussion of the multitasking of unpaid activities).

We view economic power as a broad concept that encompasses, but is not restricted to, market wages.

We exclude persons younger than age 20, men older than age 64, women older than age 61, and 20-to-23 year olds enrolled full-time in higher education. The different age restrictions by gender approximately reflect the different ages at which men and women are eligible to receive pensions in Australia.

Observations missing data on our explanatory variables are also dropped. The variables most likely to be missing data are non-labor and gift income. Paid work time is missing for a small number of observations and is top-coded at 80 hours for men and 65 hours for women, approximately the top percentile in each case.

This question is answered to the nearest minute in all HILDA waves except the first; in 2001, it is answered to the nearest hour. In our models, any difference in the average measured quantity of housework caused by this change in granularity across reporting years is captured by year dummies.

Our results are robust to excluding all 2001 observations.

In order to test whether the effect of labor market events on housework time is temporary or more permanent, it is necessary to have information pertaining to events in consecutive years. Some couples have gaps as a result of missing interview data. To accommodate such couples, we treat the pre- and post-gap data as if they were from distinct couples—referring to these as “couple spells.” Thus, in estimating our fixed effects models, we actually have 5416 fixed effects in the full sample and 4016 fixed effects in the dual-earner sample. The distribution of spell lengths reported in Table 1 is constructed for these couple spells rather than for couples per se. This complication also skews the distribution towards shorter durations.

Ideally, we would like to also be able to control for each partner’s wealth, which likely also influences intra-household bargaining power. Unfortunately, data on asset ownership are only available every fourth year in HILDA, and requiring such information would substantially alter the sample composition.

Burda et al. (2013) provides evidence that in rich, non-Catholic countries, men’s and women’s productive work hours are approximately equal.

Note that our fixed effects specification already accommodates, via those fixed effects, individuals who consistently spend less time on housework in order to increase their chances of promotion.

As more than twenty equations are estimated, it is not unexpected to find one coefficient significant at the 5% level.

That his housework time rises less than hers following a termination is in line with findings by Gough and Killewald (2011).

The household effect is literally the sum of his effect and her effect.

An instrumental variables strategy could be used to control for the possible endogeneity of labor market hours in determining housework time, but as in many complex empirical settings, it is difficult if not impossible to identify appropriate instruments. We are not aware of any policy changes that could be used and, as illustrated earlier, the labor market events themselves do not satisfy the necessary conditions either.

We re-ran these models with the full sample including dummy variables to identify those observations where he was not employed and those where she was not employed. Results were very similar to those reported here, with a slight decline in statistical significance. When we interact these dummy variables with the variables capturing labor market events, we see some evidence that his housework time responds more to her promotions when he is not employed.

Exceptions are his promotions and terminations, which have the expected long-run effect on her housework time but perverse once-off effects that are significant in the case of terminations in the dual-earner sample.

We conducted sensitivity tests on our main results by including both earnings and labor market events simultaneously. This is possible only for a subset of the dual-earner sample. The results of these tests indicate that earnings are not statistically significant unless controls for paid work hours are included. In that case, own earnings are significantly negatively related to own housework time, and his earnings are significantly positively related to her housework time. The associations between housework time and labor market events are less significant when including these controls, suggesting that labor market events are proxying for changes in earnings power, in line with our hypothesis.

That we find housework time is significantly lower for cohabiting but not married men after he is promoted or she is fired provides some evidence that married couples are more invested in or better informed about their relationship and less likely to respond to labor market events.

A handful of values indicating expenditures above $1000 per week were judged to be implausible and recoded as missing.

While we would like to model maid service as well, the data on maid service available in HILDA is inadequate to produce meaningful results. We did experiment with models of the number of times meals were eaten out, for which three waves of data are available. Using these data, we find that dual-earner couples eat out more and that households in which a partner has been promoted eat more meals out than households experiencing no labor market events. We also find that housework time reported by other household members—arguably another form of outsourcing—falls when she is terminated and rises when he is terminated, both overall and relative to the changes observed for those experiencing no labor market events.

Aguiar and Hurst (2007) and Grossbard and Amuedo-Dorantes (2007) also find gender differences in behavior by education level. Aguiar and Hurst, using USA time-diary data from 2003, find that men with less than a high school education spend 12.9 hours per week on housework, as compared to 13.7 hours for those with a college degree—a difference of 0.8 hours. Women with less than a college degree report spending 26.2 hours per week on housework, as compared to 20.8 hours for women with a college degree—a difference of 5.4 hours. Differences by education level in the levels and impact of unpaid labor time have been conjectured by prior authors (e.g., Grossbard and Amuedo-Dorantes 2007 and Gimenez-Nadal and Sevilla 2016) to result from differences in preferences or ideology for people of different education levels. For example, Grossbard and Amuedo-Dorantes (2007) report that while a higher male-to-female sex ratio gives women more power to reduce their labor supply, that impact is attenuated for less-educated married women. The authors conjecture that this is because less-educated couples prefer a more gendered division of labor, all else equal.

That men’s terminations might, particularly for less-educated samples, be associated with a reduction in men’s and an increase in women’s housework time could be a consequence of an injury or sickness that negatively influences both his ability to work for pay and his ability to work in the home. However, we find no evidence that either the negative association between men’s terminations and men’s housework time or the positive association between men’s terminations and women’s housework time is driven by long-term health shocks.

Our findings are consistent with those of Killewald and Gough (2010) who find that low-earning women change their housework hours more than others. They hypothesize that such women initially spend more time on housework and find it easier and cheaper to outsource or forego housework than women earning higher wages, who have already made the easy adjustments.

Notably, even when we control for earnings, men in less-educated households still reduce their housework time following either a promotion or a termination.

References

Aguiar M, Hurst E (2007) Measuring trends in leisure: the allocation of time over five decades. Q J Econ 122(3):969–1006

Álvarez B, Miles D (2003) Gender effect on housework allocation: evidence from Spanish two-earner couples. J Popul Econ 16(2):227–242

Baxter J, Hewitt B (2013) Negotiating domestic labor: women’s earnings and housework time in Australia. Fem Econ 19(1):29–53

Baxter J, Hewitt B, Haynes M (2008) Life course transitions and housework: marriage, parenthood, and time on housework. J Marriage Fam 70(2):259–272

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Becker GS (1985) Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. J Labor Econ 3(1):S33–S58

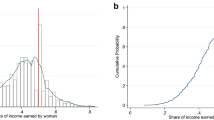

Bertrand M, Kamenica E, Pan J (2015) Gender identity and relative income within households. Q J Econ 130(2):571–614

Bittman M, England P, Folbre N, Sayer L, Matheson G (2003) When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. Am J Sociol 109(1):186–214

Blood RO, Wolfe DM (1960) Husbands and wives: the dynamics of married living. Free Press, New York

Bredtmann J (2014) The intra-household division of labor: an empirical analysis of spousal influences on individual time allocation. Labour 28(1):1–39

Brines J (1994) Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home. Am J Sociol 100(3):652–688

Browning M, Chiappori PA (1998) Efficient intra-household allocations: a general characterization and empirical tests. Econometrica 66(6):1241–1278

Burda MC, Hamermesh DS (2010) Unemployment, market work and household production. Econ Lett 107:131–133

Burda M, Hamermesh DS, Weil P (2013) Total work and gender: facts and possible explanations. J Popul Econ 26(2):239–261

Connelly R, Kimmel J (2015) If you're happy and you know it: how do mothers and fathers in the U.S. really feel about caring for their children? Fem Econ 21(1):1–34

Connelly R, Kimmel J (2009) Spousal influences on parents’ non-market time choices. Rev Econ Household 7(4):361–394

Cunningham M (2008) Influences of gender ideology and housework allocation on women’s employment over the life course. Soc Sci Res 37:254–267

Gimenez-Nadal JI, Sevilla A (2016) Intensive mothering and well-being: the role of education and child care activity. IZA Discussion Paper 10023

Gough M, Killewald A (2011) Unemployment in families: the case of housework. J Marriage Fam 73:1085–1100

Greenstein TN (1996) Husbands’ participation in domestic labor: interactive effects of wives’ and husbands’ gender ideologies. J Marriage Fam 58:585–595

Greenstein TN (2000) Economic dependence, gender, and the division of labor in the home: a replication and extension. J Marriage Fam 62:322–335

Grossbard-Shechtman A (1984) A theory of allocation of time in markets for labour and marriage. Econ J 94:863–882

Grossbard-Shechtman S (2003) A consumer theory with competitive markets for work in marriage. J Socio-Econ 31:609–645

Grossbard S, Amuedo-Dorantes C (2007) Cohort-level sex ratio effects on women’s labor force participation. Rev Econ Household 5:249–278

Gupta S, Ash M (2008) Whose money, whose time? A nonparametric approach to modeling time spent on housework in the United States. Fem Econ 14(1):93–120

Hersch J, Stratton LS (1994) Housework, wages, and the division of housework time for employed spouses. Am Econ Rev 84(2):120–125

Jenkins SP, O’Leary NC (1995) Modelling domestic work time. J Popul Econ 8(3):265–279

Kalenkoski CM, Foster G (2008) The quality of time spent with children in Australian households. Rev Econ Household 6(3):243–266

Kalenkoski CM, Foster G (2016) Introduction. In Kalenkoski CM, Foster G (eds) The Economics of Multitasking. Palgrave-MacMillan, New York, pp. 1–5

Killewald A, Gough M (2010) Money isn’t everything: wives’ earnings and housework time. Soc Sci Res 39:987–1003

Kimmel J, Connelly R (2007) Mothers’ time choices: caregiving, leisure, home production, and paid work. J Hum Resour 42(3):643–681

Krueger AB, Mueller AI (2012) The lot of the unemployed: a time use perspective. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(4):765–794

Lee Y, Waite LJ (2005) Husbands’ and wives’ time spent on housework: a comparison of measures. J Marriage Fam 67:328–336

Lundberg S, Pollak RA (1996) Bargaining and distribution in marriage. J Econ Perspect 10(4):139–158

OECD (2011) Cooking and caring, building and repairing: unpaid work around the world. In Society at a Glance 2011: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing

Pedulla DS, Thebaud S (2015) Can we finish the revolution? Gender, work-family ideals, and institutional constraint. Am Sociol Rev 80(1):116–139

Ramey VA (2009) Time spent in home production in the twentieth-century United States: new estimates from old data. J Econ Hist 69(1):1–47

Rapoport B, Sofer C, Solaz A (2011) Household production in a collective model: some new results. J Popul Econ 24(1):23–45

Robinson JP (1985) The validity and reliability of diaries versus alternative time use measures. In: Juster FT, Stafford FP (eds) Time, goods, and well-being. Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pp 33–62

Shelton BA, John D (1993) Does marital status make a difference? J Fam Issues 14(3):401–420

Stancanelli EGF, Stratton LS (2014) Maids, appliances, and couples’ housework: the demand for inputs to domestic production. Economica 81(323):445–467

Stratton LS (2012) The role of preferences and opportunity costs in determining the time allocated to housework. Am Econ Rev 102(3):606–611

Watson N, Wooden M (2012) The HILDA Survey: a case study in the design and development of a successful household panel study. Longitudinal Life Course Stud 3(3):369–381

West C, Zimmerman DH (1987) Doing gender. Gender Soc 1(2):125–151

Zamora B (2011) Does female participation affect the sharing rule? J Popul Econ 24(1):47–83

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions.

This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute. We thank Deborah Cobb-Clark, Joyce Jacobsen, Charlene Kalenkoski, Terra McKinnish, Paco Perales Perez, and seminar participants at Monash University and at the ANU-hosted Labour Econometrics Workshop in 2016 for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We are also greatly indebted to James Stratton for outstanding research assistance and to the anonymous referees of this journal for their suggestions. All errors remain ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Foster, G., Stratton, L.S. Do significant labor market events change who does the chores? Paid work, housework, and power in mixed-gender Australian households. J Popul Econ 31, 483–519 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-017-0667-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-017-0667-7