Abstract

Purpose

Suicide and self-harm by pesticide self-poisoning is common in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Alcohol is an important risk factor for self-harm; however, little is known about its role in pesticide self-poisoning. This scoping review explores the role that alcohol plays in pesticide self-harm and suicide.

Methods

The review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review guidance. Searches were undertaken in 14 databases, Google Scholar, and relevant websites. Articles were included if they focussed on pesticide self-harm and/or suicide and involvement of alcohol.

Results

Following screening of 1281 articles, 52 were included. Almost half were case reports (n = 24) and 16 focussed on Sri Lanka. Just over half described the acute impact of alcohol (n = 286), followed by acute and chronic alcohol use (n = 9), chronic use, (n = 4,) and only two articles addressed harm to others. One systematic review/meta-analysis showed increased risk of intubation and death in patients with co-ingested alcohol and pesticides. Most individuals who consumed alcohol before self-harming with pesticides were men, but alcohol use among this group also led to pesticide self-harm among family members. Individual interventions were recognised as reducing or moderating alcohol use, but no study discussed population-level alcohol interventions as a strategy for pesticide suicide and self-harm prevention.

Conclusion

Research on alcohol’s role in pesticide self-harm and suicide is limited. Future studies are needed to: further assess the toxicological effects of combined alcohol and pesticide ingestion, explore harm to others from alcohol including pesticide self-harm, and to integrate efforts to prevent harmful alcohol use and self-harm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Methods

Search strategy

This scoping review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute guidance on scoping reviews [23]. As the literature in this field was expected to be limited and diverse, a scoping review was considered appropriate. No protocol was registered. The search strategy was developed with support from a university librarian and used a combination of terms related to pesticides, alcohol use, self-harm, and suicide were adapted for each database (Supplementary Table 1) and citation linking was conducted for all included articles. Supplementary searches were undertaken using Google Scholar and websites of relevant global organisations, including WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations Office for Project Services, and Pesticide Action Network International. All searches were conducted on 3 March 2022.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included if they: (i) focussed on pesticide suicide and/or self-harm, and (ii) assessed involvement of alcohol in relation to pesticide suicide and/or self-harm (i.e. not just any method of suicide), (iii) were published in any language, (iv) were published since 2001 (as since then several countries around the world have banned highly hazardous pesticides [HHPs], which led to increased attention to risk factors for pesticide self-harm and suicide), and (v) were empirical articles, editorials, commentaries or reviews published in peer-reviewed journals; or research reports; government reports; book chapters; or conference abstracts. Articles were excluded if they: (i) had a broader focus on suicide generally (e.g. Widger [24]), providing few examples or cases and with no detailed discussion or analysis of alcohol’s role in pesticide self-harm, (ii) did not specify the method of self-harm or suicide and where associations with alcohol use was not assessed specifically for pesticide self-harm or suicide.

Screening and data extraction

All articles were screened for inclusion based on title and abstract by LS and JBS. Full-text screening was performed by the same 2 researchers for 20 articles to assess level of agreement. The first ten articles yielded discrepancies in four articles; after discussion, the second ten reached full consensus (i.e. inclusion and exclusion criteria were clarified). LS screened all full-text records and extracted information using a pre-determined data extraction form: (i) year of publication, (ii) study location, (iii) study design, (iv) how alcohol use was assessed, (v) how alcohol use was involved in pesticide suicide and/or self-harm, (vi) key findings, and (vii) if and how any alcohol interventions were discussed as a strategy for suicide and self-harm prevention. For articles in languages other than English [25], Google Translate was used to screen full-text articles. One article in Spanish was extracted by LS who has an independent level of proficiency, though supported with Google Translate, recognised as a valid method [26].

Data synthesis

Descriptive information was summarised in table format. The process of exploring common themes across included articles was iterative and informed the synthesis of findings, in addition to the pre-determined aspects of the data extraction form. LS developed the key themes, which were discussed with JBS and the wider research team. Thematic analysis [27] was used to synthesise the findings with a combination of deductive (pre-determined themes based on existing knowledge which were acute/chronic alcohol use and recognition of interventions) and inductive approaches (toxicological effects, gender and harm to others). The role of alcohol use was assessed as acute (as determined by self-report, clinical observation, or BAC), chronic (evidence of harmful, hazardous or dependent alcohol use, or overall alcohol use, as per self-report, clinical observation or assessment using diagnostic criteria such as ICD-10), or as harm to others (impact on family members or others from an individual’s alcohol use).

Results

Summary of included articles

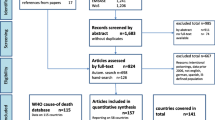

Following screening of 1281 records, 52 articles were included (Fig. 1). The articles covered a broad range of study designs and publication types. Most studies were quantitative, including case reports (n = 24), cohort (n = 9), case series (n = 7), cross-sectional (n = 5), case–control (n = 3), case series (n = 2), and before-and-after (n = 1) (Table 1). Of the remaining articles, three were qualitative (interviews and focus group discussions) and four were reviews.

Just under half of articles were from HICs (n = 24, 18 were case reports), followed by lower–middle (n = 22, four were case reports), upper–middle-income countries (n = 2, both case reports), and two had a global or regional (Asia) focus. Notably, the 20 epidemiological studies were from only 5 countries: Sri Lanka (n = 10), India (n = 4), Korea (n = 4), Taiwan (n = 2), and Spain (n = 1). Most studies related to hospital settings (n = 37), followed by community (n = 7) and autopsy (n = 6). In the 45 empirical studies that assessed alcohol use in relation to pesticide self-poisoning just over half (n = 26) described the method for assessing alcohol use. One article was published in Spanish [28] and the remaining articles in English. Characteristics of all included case reports are summarised in Table 2 and characteristics of all other included studies in Table 3.

Toxicological aspects of concurrent alcohol and pesticide ingestion

Dhanarisi et al. [58] reviewed studies that reported on co-ingestion of alcohol and pesticides. Fourteen studies were included in this review and no difference was found in length of hospital stay or amount of pesticide ingested, in studies which measured these indicators. In the one study, Eddleston et al. [60] that measured concentration of pesticide (dimethoate) patients who consumed alcohol also had higher pesticide concentration. Meta-analytical results from this same review indicated that patients who co-ingested alcohol were more likely to require intubation (OR = 8.0, 95% CI 4.9–13.0, p < 0.0001) and more likely to die from pesticide self-poisoning (OR = 4.9, 95% CI 2.9–8.2, p < 0.0001) [58]. The authors noted that higher risk of death could be related to higher suicidality, underlying health conditions, or higher amount of pesticide consumed. While alcohol appears to have a contributory effect to fatal outcomes, the authors concluded that “the data presented are insufficient to conclude how this secondary contributory factor would be responsible for increased fatal outcomes”. Furthermore, they highlighted that chronic alcohol use was not reported in most studies, which could be a confounder in the association between acute alcohol use and pesticide poisoning [58]. In addition, in relation to the amount of pesticide ingested, a toxicology review by Eddleston et al. [62] suggested that acute alcohol intoxication can cause complications due to alcohol withdrawal and alcohol cardiomyopathy, which can increase complications of tachycardia in organophosphate (OP) poisoning, impacting patient management and risk of death. The combined effect of alcohol and pesticides could explain the higher mortality among middle-aged men than women [59] and increased risk of coma [62].

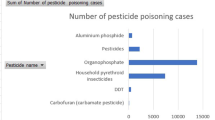

Precipitant acute alcohol use

The majority of studies in this category were epidemiological (n = 21), and in 13 of these studies, the prevalence of alcohol co-ingestion was reported. The average proportion of patients with alcohol co-ingestion was 30%, ranging from 15% in 110 patients with bispyribac poisoning in 2 hospitals in Sri Lanka [63] to 68% of 91 ‘suicidal patients’ across 5 emergency centres in the Republic of Korea [69]. One study of patients presenting to a medical centre in Taiwan only included complex suicide cases (i.e. cases with at least one other means in addition to pesticides), of whom more than half (54%) had ‘alcohol intoxication’ (assessment method not reported) with no significant difference between those with and without previous events of self-harm (‘suicide attempts’) [64]. A Sri Lankan study across three hospitals was the only study that assessed BAC and found that more than half of patients (51%) had a BAC ≥ 0.05 mg/dL and a median of 0.15 mg/dL [60].

In just over half of these studies (n = 11/21), alcohol use was assessed in specific terms, while in the remaining studies, this was described without detail. For example, Kim et al. [66] noted that those ‘under the influence of alcohol’ had consumed ‘more pesticides’ and Venugopal [75] reported that ‘the mode of ingestion’ in 20% of patients was ‘with alcohol’. Weerasinghe et al. [79] found that 28% of customers who purchased pesticides for self-harm were ‘under the influence of alcohol’ (self-reported) at the time of purchase, compared to 0.5% of customers who bought pesticides for other purposes [79].

Of the 21 studies that reported epidemiological data, 6 reported alcohol measures by gender [28, 56, 57, 60, 73, 79]. In these six studies, men predominantly self-harmed and co-ingested alcohol. In four of these studies, all patients who had co-ingested alcohol were men [28, 56, 57, 79], and in one study, 97% were men [60]. Tu et al. [73] did not stratify co-ingestion of alcohol by gender but among patients who underwent psychiatric assessment, more than eight in ten of those with an AUD were male (84%). Among all men, prevalence of AUD was 19% compared to 7% among women (p < 0.001) [73].

Precipitant chronic alcohol use

Underlying chronic alcohol use was prevalent among self-harm cases but definitions and assessment methods varied. In a Sri Lankan study, among participants who underwent a mental health module, 10% had probable alcohol dependence (DSM-IV), with an OR for probable alcohol dependence of 5.26 (95% CI 1.06–26.11), compared to controls [74]. In a hospital-based study from Taiwan, 26% of assessed patients were reported to have an AUD (DSM), with no significant difference between those who had a first and subsequent self-harm event [64]. A similar proportion was observed in a sample of patients in a general medicine ward in Kerala, India, where 23% of patients presenting at a general medicine ward had alcohol dependence, as per ICD-10 [70]. In Taiwan, at a population level, reductions in suicides were found following a paraquat ban but this was not associated with patterns of drinking [55].

Of the six case reports where chronic use was mentioned, it was not clear whether alcohol was also implicated at the time of the event in half of these studies (n = 3/6). For example, Bilics et al. [32] noted that the patient had a history of “chronic alcoholism” via medical history but there was no indication of assessment of acute alcohol consumption at the time of self-harm.

Alcohol’s harm to others

Two articles mentioned harm to others from alcohol [67, 72]. Konradsen et al. [67] explored alcohol use related to pesticide self-poisoning in Sri Lanka and found that in 40% of 159 cases, ‘alcohol misuse’ or ‘addiction’ reportedly played a role in self-harm. In half of these cases, the person who was drinking self-harmed, while in the remaining cases, family members self-harmed due to the drinking from the father of the household [67]. This was related to domestic violence, adverse impact on disposable income, shame and embarrassment [67]. Similarly, Sørensen et al. [71], in their exploration of self-harm in Sri Lanka, described alcohol as a domestic problem that exacerbated other daily life stressors, leading to self-harm. One case described how “while drunk, the man blamed his partner for the daughter’s promiscuous behaviour noting how their relatives would speak badly about them. This turned into a violent fight followed by the woman ingesting pesticides.” (p.4) [72]. Both Konradsen et al. [67] and Sørensen et al. [72] highlighted issues of gender differences; self-harm events which either involved men who self-harmed or their significant others or family members, who self-harmed in response to their own/their family members’ alcohol use.

Alcohol interventions in preventing self-harm

Just seven studies discussed the need for alcohol interventions as a strategy to prevent pesticide self-harm and suicide. In their study of pesticide vendors’ role in preventing pesticide self-harm in Sri Lanka, Weerasinghe et al. [77] found that the majority of vendors (84%) increased their knowledge of the importance of not selling pesticides to individuals who were under the influence of alcohol. The authors suggested that training of vendors could help reduce pesticide self-harm, which was a favoured intervention by the stakeholders [78]. Dhanarisi et al. [56], in a Sri Lankan context, called for public health campaigns to reduce alcohol use and increase awareness of negative effects on health from drinking. Eddleston et al. [59], also in Sri Lanka, acknowledged that reducing alcohol consumption is part of pesticide self-harm prevention, which required ‘community efforts’; however, this was challenging due to ‘political power’, ‘drinks industry’ and ‘illegal distilling of alcohol’. Prakruthi et al. [71] were more specific suggesting that interventions should include stress management, coping skills and treatment for alcohol dependence and depression. A case report by Fellmeth et al. [40] described a suicide of a couple in a refugee camp, in which the authors noted the need for early identification of alcohol dependence and mental disorders in these settings.

Discussion

This review highlighted the importance of alcohol in pesticide self-harm and suicide. Few studies explored the impact of alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol use on health outcomes, making it difficult to assess whether increased risks for patients who have co-ingested alcohol is a factor of acute or chronic alcohol use, or both [58]. As just under one-third of individuals (almost exclusively men) who self-poisoned with pesticides had also consumed alcohol, there is potential for alcohol prevention efforts at a population and community level. However, recognition of broader level alcohol prevention was not discussed in any included articles, despite it being an important public health strategy for suicide prevention.

Alcohol’s role in pesticide self-harm

Our findings demonstrate the importance of alcohol consumption in pesticide self-harm and suicide. As Dhanairisi et al. highlighted in their systematic review/meta-analysis, few studies have assessed dose of pesticide and outcomes among patients with alcohol co-ingestion, and with varying results [58]. In a prospective case series from Sri Lanka, which found that the dose of profenofos was not associated with outcomes [56], we question whether alcohol was behaviourally mediated in relation to self-harm. More studies are needed to understand not only the toxicological effects but also the mechanisms of alcohol consumption in pesticide self-harm. This will help explain why risk of death is higher in patients with alcohol co-ingestion.

The broader range of harm from alcohol use, or misuse, was less frequently explored. The most detailed accounts came from Konradsen et al. [67] who described how self-poisoning in Sri Lanka had become a response to difficult situations and a powerful communication method. Similarly, Marecek and Senadheera [73] described this phenomena as ‘dialogue suicide’, as opposed to monologue suicides, characterised as being solitary and inward focussed acts—as often seen in HIC settings [80]. Similarly, other qualitative studies on the link between alcohol and self-harm in Sri Lanka found that alcohol played a direct role in men’s self-harm [72]. Women were indirectly influenced by someone else’s alcohol use and interpersonal conflict often led to self-harm through which women would seek to teach their husbands a lesson to enable the drinker to moderate their alcohol use [72]. Studies from Uganda and South Africa, which explored all methods of suicide, found both direct and indirect impacts from alcohol in suicide cases [81, 82], with early onset of alcohol use and current alcohol dependence being particularly important factors [82]. Importantly, in our review, included quantitative studies from hospital-based samples did not elucidate whether patients may have engaged in acts of pesticide self-poisoning due to someone else’s alcohol use.

Geographical clustering of research

This review identified papers from several countries but, as expected, many focussed on Sri Lanka, which has been the epicentre for suicide prevention research over several decades [83]. Here, research capacity has developed to carry out large-scale self-poisoning studies, including via international research collaborations [86, 87]. Specifically, numerous studies have been conducted on self-harm and suicide, including on the steep reductions in suicide rates following bans of several kinds of pesticides [83,84,85]. However, more research is needed in other countries to explore the link between alcohol and pesticide self-poisoning. We identified only a few studies from India, and none from China, though these two countries account for more than four in ten (44%) of all suicides globally [1], with pesticides among the most common means [8, 87], and alcohol use an important risk factor [89, 90]. Furthermore, this review found just one included record, a case study [45], from the African region. This reflects scarcity of data on pesticide suicide in the African region [2], despite evidence suggesting pesticide poisoning is a common method of suicide [91]. While more research in other countries is needed, it is worth noting the challenges of measuring alcohol consumption [92], including in Indigenous peoples [93]. To address these challenges, in an Australian context, an interactive and visual tablet computer-based survey tool has been developed and validated to help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples describe their alcohol consumption [94,95,96]. Such a tool may have the utility to improve epidemiological data on alcohol consumption, self-harm, and suicide in other contexts.

The global increases in alcohol use at the overall population level makes the need for further research in this area even greater. Projections suggest alcohol per capita will continue to rise in the SEAR, Western Pacific Region (WPR), Eastern Mediterranean Region (albeit a small increase from a low baseline) and Region of the Americas—leading to an overall increase in global alcohol per capita consumption. Past changes in alcohol use levels in SEAR and WPR have been driven by sharp increases in India and China [13], which along with knowledge of burden of suicide in these regions further emphasises the need to explore the combination of these two public health issues.

Description of methods and sociodemographic factors

In this review, few studies specifically set out to study the role of alcohol use in pesticide self-harm and suicide. This might explain why descriptions of methods used to assess alcohol use and further details about context drinking were limited. We were particularly interested in exploring the role of gender, but of the 20 studies reporting on epidemiological data, only 6 reported on alcohol measures (acute or chronic alcohol use) by gender [28, 56, 57, 60, 73, 79]. Furthermore, the method used to assess alcohol use was lacking in some papers and there was no uniformity in the way alcohol was assessed. In several case studies, the patient or deceased was noted to have been under the influence of alcohol, though this was not verified through BAC testing. Similarly, there was no uniformity in the way chronic alcohol use was assessed, as impact of acute and chronic alcohol use has particular relevance for populations where drinking is impacted by context [97]. The risk of self-harm (‘suicide attempts’) at lower levels of alcohol use increases the risk sevenfold while heavy drinking increases the risk by 37 times [15]. Comparable measures of alcohol use that can be stratified may, therefore, be needed in the future research to assess risk from any alcohol use as well as magnitude of risk at different levels. Limitations on reporting of data on method of suicide [15] made it difficult to draw conclusions about alcohol use and lethality of method or added toxicological effects from co-ingestion. On average, in our review, alcohol was involved in one-third of the cases of pesticide self-harm or suicide, which reflects the overall prevalence of reported alcohol use in previous studies including all methods of suicide [98].

Preventing pesticide self-poisoning

While few articles in this scoping review acknowledged how alcohol interventions at an individual- or population level can help to prevent pesticide self-poisoning, there is recognition within the wider suicide prevention field. Alcohol has been integrated in the WHO’s Live Life document which provides Member States with an implementation guide to suicide prevention [98]. In Sri Lanka, a policy document outlining recommendations for action in suicide prevention emphasises AUD, specifically, as a risk factor in suicidal behaviour [99] and the need to address this within a suicide prevention framework [100]. In addition to a suicide prevention approach, strengthened alcohol policy can impact on suicide rates. In a systematic review, Kӧlves et al. [101] showed that across studies from Europe (including Russia and USSR) and the US, there was evidence that suicide rates have changed alongside alcohol policy changes, particularly by changing availability of alcohol (restricting or increasing availability) and pricing policies [102]. These are known as the ‘best buys’ to reduce harmful use of alcohol, along with advertising restrictions [102], which should be adapted to national contexts [103]. Whereas stricter alcohol policy is needed in South-East Asia to achieve the 2030 SDG target of reducing alcohol per capital consumption by 10% [20], other interventions are needed to target the widespread use of illicit alcohol. In Sri Lanka, a community-based participatory intervention showed promising results for moderating alcohol use [104]. If proved effective at larger scale, such interventions might be relevant in other contexts too, as it has been highlighted that in Sri Lanka alcohol consumption has an important social role and abstinence-based interventions may therefore not be successful [24, 72]. These types of community-based approaches may be effective, in addition to population-level interventions, to address contextual factors such as gender-based violence, mental health issues, poverty, and other stressors that co-occur with harmful alcohol use.

Preventing suicide by pesticide self-poisoning can also be effectively reduced by banning HHPs [105]. In Bangladesh, Chowdhury et al. [106] showed that the reduction in suicide deaths following pesticide bans was not associated with population-level ‘alcohol misuse patterns’ and Gunnell et al. [85] also found that declining suicide rates in Sri Lanka were not related to a decline in alcohol sales (a proxy for population-level alcohol use). As these reductions were independent of overall alcohol consumption, it suggests that targeted alcohol interventions alongside bans of the most acutely toxic pesticides may be a way forward to reduce suicide and self-harm rates.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review was set up with input from a university librarian, to ensure the search strategy was comprehensive; however, the protocol was not registered prior to undertaking the study. The team involved in the review is multidisciplinary and represented a range of regions including South-East Asia, Africa, Europe, and Western Pacific. The review has some limitations that should be acknowledged. While the title and abstract screening was done by two researchers independently, only a subset of full-text articles were screened by two reviewers and the remaining articles were screened by one researcher. However, continuous discussion between two researchers ensured clarity on inclusion criteria. Articles of any language were eligible for inclusion in this review; however, the searches were only conducted in English language databases.

Conclusions

Alcohol plays an important role in pesticide suicide and self-harm, both for treating pesticide self-poisoning and as an underlying factor for self-harm among people who drink and their family members. Research in this area has been conducted in a few countries in South-East Asia and little attention has been paid to harm to others from alcohol. More research is needed to incorporate validated measures of chronic and acute alcohol use as well as alcohol’s harm to others into surveillance studies of pesticide self-harm and suicide studies. Furthermore, efforts to prevent harmful use of alcohol should be integrated into all pesticide suicide prevention and treatment efforts.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Change history

29 August 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02558-1

References

Naghavi M (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 364:l94. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l94

Mew EJ, Padmanathan P, Konradsen F, Eddleston M, Chanc S, Phillips MR, Gunnell D (2017) The global burden of fatal self-poisoning with pesticides 2006–15: Systematic review. J Affect Disord 219:93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.002

Eddleston M, Phillips MR (2004) Self poisoning with pesticides. BMJ 328:42–44. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7430.42

National Crime Records Bureau India (2021) Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India – Tables https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/ADSI-2021/ADSI2021_Tables.html [Accessed 10 November 2022]

Department of Census & Statistics Sri Lanka (2010) Method of suicide by year and sex http://www.statistics.gov.lk/GenderStatistics/StaticalInformation/SpecialConcerns [Accessed 10 November 2022]

Ghimire R et al (2022) Intentional pesticide poisoning and pesticide suicides in Nepal. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 60(1):46–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2021.1935993

Utyasheva L, Sharma D, Ghimiri R, Karunarathne A, Robertson G, Eddleston M (2021) Suicide by pesticide ingestion in Nepal and the impact of pesticide regulation. BMC Public Health 21(1):1136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11155-3

Page A, Liu S, Gunnell D, Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Wang L, Zhou M (2017) Suicide by pesticide poisoning remains a priority for suicide prevention in China: Analysis of national mortality trends 2006–2013. J Affect Disord 208:418–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.047

Arya V, Page A, Armstrong G, Kumar GA, Dandona R (2021) Estimating patterns in the under-reporting of suicide deaths in India: comparison of administrative data and Global Burden of Disease Study estimates, 2005–2015. J Epidemiol Commun Health 75(6):550–555. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-215260

World Health Organization (2014) Preventing Preventing suicide suicide A global imperative A global imperative https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241564779 [Accessed 10 May 2023]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013) Self‑harm - Quality standard [QS34] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS34 [Accessed 10 May 2023]

Conner KR, Ilgen MA (2016) Substance Use Disorders and Suicidal Behavior. In: O’Connor RC, Platt S, Gordon J (Eds) The International Handbook of Suicide Prevention. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 110–123

World Health Organization (2018) Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 [Accessed 10 May 2023]

Amiri S, Behnezhad S (2020) Alcohol use and risk of suicide: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Addict Dis 38(2):200–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1736757

Borges G, Bagge CL, Cherpitel CJ, Conner KR, Orozco R, Rossow I (2017) A meta-analysis of acute use of alcohol and the risk of suicide attempt. Psychol Med 47(5):949–957. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002841

Room R, Ferris J, Laslett A-M, Livingston M, Maguvin J, Wilkinson C (2010) The drinker’s effect on the social environment A. Conceptual framework for studying alcohol’s harm to others. Int J Environ Res Public Health 7(4):1855–1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7041855

Room R, Laslett A-M, Jiang H (2016) Conceptual and methodological issues in studying alcohol’s harm to others. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs 33(5–6):455–478. https://doi.org/10.1515/nsad-2016-003

United Nations (2023) Sustainable Development Goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals [Accessed 10 May 2023]

GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators (2018) Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 392(10152): 1015-1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2

Sornpaisarn B, Shield K, Manthey J, Limmade Y, Low WY, Thang VV, Rehm J (2020) Alcohol consumption and attributable harm in middle-income South-East Asian countries: Epidemiology and policy options. Int J Drug Policy 83:102856–102856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102856

Jayasinghe NRM, Foster JH (2008) Acute poisoning and suicide trends in Sri Lanka: Alcohol a cause for concern. Aust NZ J Public Health 32(3):290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00234.x

Jayasinghe NRM, Foster JH (2011) Deliberate self-harm/poisoning, suicide trends. The link to increased alcohol consumption in Sri Lanka. Arch Suicide Res 15(3):223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2011.589705

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alezander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H (2021) Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 19(1): 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Widger T (2015) Suicide in Sri Lanka: The anthropology of an epidemic. Routledge, New York

Walpole SC (2019) Including papers in languages other than English in systematic reviews: important, feasible, yet often omitted. J Clin Epidemiol 111:127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.004

Balk EM, Chung M, Chen ML, Trikalinos TA, Chang LKW (2013) Assessing the accuracy of google translate to allow data extraction from trials published in non-english languages. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK121304/ [Accessed 10 May 2023]

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitat Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Suárez Solá MS, González Delgado F, Rubio C, Hardisson A (2004) Estudio de seis suicidios consumados por ingestión de carbamatos en el partido judicial de La Laguna (Tenerife) durante el período 1998–2002. Rev. Toxicol 21: 108–112. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/919/91921309.pdf [Accessed 10 May 2023]

Altay S, Cakmak HA, Boz GC, Koca S, Velibey Y (2011) Prolonged coagulopathy related to a coumarine rodenticide in a young patient: Superwarfarin poisoning. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi Arsivi 39(SUPPL. 1): 165. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC126389 [Accessed 10 May 2023]

Aardema H, Meertens JHJM, Ligtenberg JJM, Peters-Polman OM, Tulleken JE, Zijlstra JG (2008) Organophosphorus pesticide poisoning: cases and developments. Neth J Med 66(4):149–153

Berman AJ, Kessler BD, Nogar JN, Sud P (2015) 186. Intentional ingestion of malathion resulting in prolonged hospitalization with delayed intubation. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 53(7):725–726

Bilics G, Héger J, Pozsgai É, Bajzik G, Nagy C, Somoskӧvi C, Varga C (2020) Successful management of zinc phosphide poisoning - A Hungarian case. Int J Emerg Med 13(1):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00307-8

Boumba VA, Rallis GN, Vougiouklakis T (2017) Poisoning suicide with ingestion of the pyrethroids alpha-cypermethrin and deltamethrin and the antidepressant mirtazapine: A case report. Forensic Sci Int 274:75–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.11.023

Boumrah Y, Gicquel T, Hugbart C, Baert A, Morel I, Bouvet R (2016) Suicide by self-injection of chlormequat trademark C5SUN®. Forensic Sci Int 263:e9–e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.03.007

Brvar M, Okrajšek R, Kosmina P, Starič F, Kapš R, Koželj G, Bunc M (2008) Metabolic acidosis in prometryn (triazine herbicide) self-poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 46(3):270–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650701665126

Chao LK, Fang TC (2016) Dialysis catheter-related pulmonary embolism in a patient with paraquat intoxication. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi 28(4):166–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcmj.2015.05.005

Chomin J, Heuser W, Nogar J, Ramnarine M, Stripp R, Sud P (2017) Delayed fatality after chlorfenapyr ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 55(7):765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.035

Danescu I, Macovei R, Caragea G, Ionica M (2015) 212. Acute pancreatitis in carbofuran poisoning: a case report. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 53(4):332

Ellsworth H, Lintner CP, Kinnan MR, Kwon SK, Cole JB, Harris CR (2012) 325. A case of delayed neuropathy following an intentional carbamate ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 50(4):359

Fellmeth G, Oo MM, Lay B, McGready R (2016) Paired suicide in a young refugee couple on the Thai-Myanmar border. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-215527

Fuke C, Nagai T, Ninomiya K, Fukasawa M, Ihama Y, Miyazaki T (2014) Detection of imidacloprid in biological fluids in a case of fatal insecticide intoxication. Leg Med (Tokyo) 16(1):40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2013.10.007

Gupta AK, Su MK, Chan GM, Lee DC, McGuigan MA, Carracio TR, Greller HA (2009) Mortality after suicide ingestion of aluminium phosphide. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 47(7):723

Lam G, Mithani R, Ahn J, Cohen S, Pillai A (2010) 15. Hurting on the inside: Black esophagus after suicide attempt with acetaminophen and rat poison. Am J Gastroenterol 105(Suppl 1):S6

Martinez MA, Ballesteros S (2012) Two suicidal fatalities due to the ingestion of chlorfenvinphos formulations: Simultaneous determination of the pesticide and the petroleum distillates in tissues by gas chromatography-flame-ionization detection and gas chromatography- mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol 36(1):44–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkr014

Ntshalintshali SD, Manzini TC (2017) Paraquat poisoning: Acute lung injury - a missed diagnosis. S Afr Med J 107(5):399–401. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i5.12306

Oh JS, Choi KH (2014) Methemoglobinemia associated with metaflumizone poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 52(4):288–290. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2014.900180

Pankaj M, Krishna K (2014) Acute organophosphorus poisoning complicated by acute coronary syndrome. J Ass Physicians India 62:614–616

Park JT, Choi KH (2018) Polyneuropathy following acute fenitrothion poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 56(5):385–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2017.1378354

Planche V, Vergnet S, Auzou N, Bonnet M, Tourdias T, Tison F (2019) Acute toxic limbic encephalopathy following glyphosate intoxication. Neurology 92(11):534–536. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007115

Ruwanpura R (2009) A complex suicide. Ceylon Med J 54(4):132–134. https://doi.org/10.4038/CMJ.V54I4.1457

Yeh IJ, Lin TJ, Hwang DY (2010) Acute multiple organ failure with imidacloprid and alcohol ingestion. Am J Emerg Med 28(2):255.e1-e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2009.05.006

Yoshida S et al (2015) Much caution does no harm! Organophosphate poisoning often causes pancreatitis. J Intensive Care 3(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-015-0088-1

Abhilash KPP, Chandran J, Murugan S, Rabbi NAS, Selvan J, Jindal A, Gunasekaran K (2022) Changing trends in the profile of rodenticide poisoning. Med J Armed Forces India 78(1):S139–S144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.12.009

Alahakoon C, Dassanayake TL, Gawarammana IB, Weerasinghe VS, Buckley NA (2020) Differences between organophosphates in respiratory failure and lethality with poisoning post the 2011 bans in Sri Lanka. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 58(6):466–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1660782

Cha ES, Chang S, Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Khang Y-H, Lee WJ (2016) Impact of paraquat regulation on suicide in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol 45(2):470–479. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv304

Dhanarisi HKJ, Gawarammana IB, Mohamed F, Eddleston M (2018) Relationship between alcohol co-ingestion and outcome in profenofos self-poisoning - A prospective case series. PLoS ONE 13(7):e0200133. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.020013

Dhanarisi J, Tzotzolaki TM, Vasileva A-MD, Kjellberg MA, Hakulinen H, Vanninen P, Gawarammana IB, Mohamed F, Hovda KE, Eddleston M (2022) Osmolal and anion gaps after acute self-poisoning with agricultural formulations of the organophosphorus insecticides profenofos and diazinon: A pilot study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 130(2):320–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13686

Dhanarisi J, Perera S, Wijerarathna T, Gawarammana IB, Shihana F, Pathiraja V, Eddleston M, Mohamed F (2023) Relationship between alcohol co-ingestion and clinical outcome in pesticide self-poisoning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol Alcohol 58(1):4–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc%2Fagac045

Eddleston M, Buckley NA, Gunnell D, Dawson AH, Konradsen F (2006) Identification of strategies to prevent death after pesticide self-poisoning using a Haddon matrix. Inj Prev 12(5):333–337. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2006.012641

Eddleston M, Gunnell D, von Meyer L, Eyer P (2009) Relationship between blood alcohol concentration on admission and outcome in dimethoate organophosphorus self-poisoning. Br J Clin Pharmacol 68(6):916–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03533.x

Eddleston M (2013) Applied clinical pharmacology and public health in rural Asia–preventing deaths from organophosphorus pesticide and yellow oleander poisoning. Br J Clin Pharmacol 75(5):1175–2125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04449.x

Eddleston M (2019) Novel clinical toxicology and pharmacology of organophosphorus insecticide self-poisoning. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 59:341–360. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021842

Gawarammana IB, Roberts DM, Mohamed F, Roberts MS, Medley G, Jayamanne S, Dawson A (2010) Acute human self-poisoning with bispyribac-containing herbicide Nominee (R): a prospective observational study. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 48(3):198–202. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563651003660000

Huang WC, Yen TH, Lin L, Lin C, Juang YY, Wang BH, Lee SH (2020) Clinical characteristics of pesticide self-harm as associated with suicide attempt repetition status. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 16:1717–1726. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S258475

Kim HJ, Lee DH (2021) The characteristics associated with alcohol co-ingestion in patients visited to the emergency department with deliberate self-poisoning: Retrospective study. Signa Vitae 17(4): 108–117. https://doi.org/10.22514/sv.2021.035

Kim B, Kim EY, Park J, Ahn YM (2014) P-20-006 Suicide attempters with alcohol intoxication had equivalent suicide intent as non-drunken status suicide attempters. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 17(SUPPL. 1):86–87

Konradsen F, van der Hoek W, Peiris P (2006) Reaching for the bottle of pesticide - A cry for help. Self-inflicted poisonings in Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med 62(7): 1710–1719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.020

Kumar RD, Siddaramanna T (2016) Study of fatal poisoning cases in Tumkur region. Medico-Legal Update 16(1):73–75. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-1283.2016.00016.5

Min YH et al (2015) Effect of alcohol on death rate in organophosphate poisoned patients. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol 13(1):19–24

Noghrehchi F, Dawson A, Raubenheimer JE, Buckley NA (2022) Role of age-sex as underlying risk factors for death in acute pesticide self-poisoning: a prospective cohort study. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia) 60(2):184–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2021.1921186

Prakruthi NK, Rakesh T (2018) Pesticide self poisoning: A study of suicidal intent, psychiatric morbidity and access to pesticides. Ind J Psych 60(5):S139

Sørensen JB, Agampodi T, Sørensen BR, Siribaddana S, Konradsen F, Reinlӓnder T (2017) “We lost because of his drunkenness”: the social processes linking alcohol use to self-harm in the context of daily life stress in marriages and intimate relationships in rural Sri Lanka. BMJ Glob Health 2(4):e000462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-00046

Tu CY et al (2022) Characteristics and psychopathology of 1,086 patients who self-poisoned using pesticides in Taiwan (2012–2019): A comparison across pesticide groups. J Affect Disord 300:17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.058

van der Hoek W, Konradsen F (2005) Risk factors for acute pesticide poisoning in Sri Lanka. Trop Med Int Health 10(6):589–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01416.x

Venugopal R, Narayanasamy K, Annasamy C, Senthilkumar R, Premkumar K, Venkateswaran AR, Santhi Selvi A (2018) Yellow phosphorus as rodenticide-predictive factors of liver injury and its outcome analysis in humans consuming rodenticide on suicidal intention: A single centre tertiary care experience from South India. Hepatol Int 12(2):S360

Weerasinghe M et al (2015) Risk factors associated with purchasing pesticide from shops or self-poisoning: a protocol for a population-based case control study. BMJ Open 5(5):e007822. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007822

Weerasinghe M, Konradsen F, Eddleston M, Pearson M, Jayamanne S, Gunnell D, Hawton K, Agampodie S (2018) Vendor-based restrictions on pesticide sales to prevent pesticide self-poisoning - a pilot study. BMC Public Health 18(1):272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5178-2

Weerasinghe M, Konradsen F, Eddleston M, Pearson M, Jayamanne S, Gunnell D, Hawton K, Agampodi S (2018) Potential interventions for preventing pesticide self-poisoning by restricting access through vendors in Sri Lanka. Crisis 39(6):479–488. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000525

Weerasinghe M, Konradsen F, Eddleston M, Pearson M, Jayamanne S, Knipe D, Hawton K, Gunnell D, Agampodi S (2020) Factors associated with purchasing pesticide from shops for intentional self-poisoning in Sri Lanka. Trop Med Int Health 25(10):1198–1204. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13469

Marecek J, Senadheera C (2012) “I drank it to put an end to me”: Narrating girls’ suicide and self-harm in Sri Lanka. Contribut Indian Sociol 46(1–2):53–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0069966711046002

Kizza D, Hjelmland H, Kinyanda E, Knizek LB (2012) Alcohol and suicide in postconflict Northern Uganda: a qualitative psychological autopsy study. Crisis 33(2):95–105. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000119

Holtman Z, Shelmerdine S, London L, Flisher A (2011) Suicide in a poor rural community in the Western Cape, South Africa: experiences of five suicide attempters and their families. S Afr J Psychol 41(3):300–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124631104100

Knipe DW, Gunnell D, Eddleston M (2017) Preventing deaths from pesticide self-poisoning—learning from Sri Lanka’s success. Lancet Glob Health 5(7):e651–e652. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30208-5

Knipe DW, Metcalfe C, Fernando R, Pearson M, Konradsen F, Eddleston M, Gunnell D (2014) Suicide in Sri Lanka 1975–2012: Age, period and cohort analysis of police and hospital data. BMC Public Health 14(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-839

Gunnell D, Hewagama FR, Priyangika WD, Konradsen F, Eddleston M (2007) The impact of pesticide regulations on suicide in Sri Lanka. Int J Epidemiol 36(6):1235–1242. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym164

Dawson AH, Buckley NA (2011) Toxicologists in public health – Following the path of Louis Roche (based on the Louis Roche lecture “An accidental toxicologist in public health”, Bordeaux, 2010). ClinToxicol (Philadelphia) 49(2):94–101. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2011.554420

Widger T, Touisignant N, Eddleston M, Dawson A, Senanayake N, Sariola S, Simpson B (2022) Research as Development. Med Anthropol Theory 9(2): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.9.2.6499

Bonvoisin T, Utyasheva L, Knipe D, Gunnell D, Edddleston M (2020) Suicide by pesticide poisoning in India: a review of pesticide regulations and their impact on suicide trends. BMC Public Health 20(1):251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8339-z

Vijayakumar L, Chandra PS, Kumar MS, Pathre S, Banarjee D, Goswami T, Dandona R (2022) The national suicide prevention strategy in India: context and considerations for urgent action. Lancet Psychiatry 9(2):160–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00152-8

Li Y, Li Y, Cao J (2012) Factors associated with suicidal behaviors in mainland China: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 12(1):524. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-524

Mars B, Burrows S, Hjelmland H, Gunnell D (2014) Suicidal behaviour across the African continent: a review of the literature. BMC Public Health 14:606. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-606

Dawson DA, Room R (2000) Towards agreement on ways to measure and report drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems in adult general population surveys: the Skarpö Conference overview. J Subs Abuse 12(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00037-7

Lee KSK, Chikritzhs T, Wilson S, Wilkes AOE, Gray D, Room R, Conigrave KM (2014) Better methods to collect self-reported alcohol and other drug use data from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Drug Alcohol Rev 33(5):466–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12159

Lee KSK et al (2021) Acceptability and feasibility of a computer-based application to help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians describe their alcohol consumption. J Ethn Subst Abuse 20(1):16–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2019.1579144

Lee KSK et al (2019) Asking about the last four drinking occasions on a tablet computer as a way to record alcohol consumption in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a validation. Addict Sci Clin Pract 14(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-019-0148-2

Lee KSK et al (2019) Short screening tools for risky drinking in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: modified AUDIT-C and a new approach. Addict Sci Clin Pract 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-019-0152-6

Vichitkunakorn P, Balthip K, Geater A, Assanangkornchai S (2018) Comparisons between context-specific and beverage-specific quantity frequency instruments to assess alcohol consumption indices: Individual and sample level analysis. PLoS ONE 13(8):e0202756. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202756

Cj C, Borges G, Wilcox HC (2004) Acute alcohol use and suicidal behavior: a review of the literature. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28(s1):18S-28S. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.alc.0000127411.61634.14

World Health Organization (2021) Life Life - An implementation guide for suicide prevention in countries https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-MSD-UCN-MHE-22.02 [Accessed 10 May 2023]

Sri Lanka Medical Association (2019) Expert Committee on Suicide Prevention, Suicide Prevention in Sri Lanka: Recommendations for Action

Kõlves K, Chitty KM, Wardhani R, Vӓrnik A, de Leo D, Witt K (2020) Impact of alcohol policies on suicidal behavior: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(19):7030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197030

World Health Organization (2017) Tackling NCDs - ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-179-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 10 May 2023]

World Health Organization (2010) Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/alcohol-drugs-and-addictive-behaviours/alcohol/governance/global-alcohol-strategy [Accessed 10 May 2023]

Siriwardhana P, Dawson AH, Abeyasinge S (2013) Acceptability and effect of a community-based alcohol education program in rural Sri Lanka. Alcohol Alcohol 48(2):250–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/ags116

Gunnell D, Knipe D, Chang S, Pearson M, Konradsen F, Lee WJ, Eddleston M (2017) Prevention of suicide with regulations aimed at restricting access to highly hazardous pesticides: a systematic review of the international evidence. Lancet Glob Health 5(10):e1026–e1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30299-1

Chowdhury FR, Dewan G, Verma VR, Knipe DW, Isha IT, Faiz MA, Gunnell DJ, Eddleston M (2018) Bans of WHO Class I pesticides in Bangladesh-suicide prevention without hampering agricultural output. Int J Epidemiol 47(1):175–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx157

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Donna Watson, Academic Support Librarian at University of Edinburgh, for her support with developing the search strategy for this scoping review. LS, MP, JBS, and MW are supported by the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention. The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention is funded by a grant from Open Philanthropy, at the recommendation of GiveWell. KL is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council via an Ideas Grant (APP1183744).

Funding

The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention is funded by a grant from Open Philanthropy, at the recommendation of GiveWell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS developed the scoping review protocol, ran the searches, screened articles, extracted data and drafted the manuscript. JBS developed the scoping review protocol, did title and abstract screening, did initial full-text screening, reviewed data extraction, and contributed to the draft manuscript and several iterations of the manuscript. All the other authors reviewed the protocol, the extracted data and the draft manuscript. All the authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article funding note was wrongly given. it has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schölin, L., Lee, K.S.K., London, L. et al. The role of alcohol use in pesticide suicide and self-harm: a scoping review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 59, 211–232 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02526-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02526-9